River Clyde

The River Clyde (Scottish Gaelic: Abhainn Chluaidh, pronounced [ˈavɪɲ ˈxl̪ˠuəj], Scots: Clyde Watter, or Watter o Clyde) is a river that flows into the Firth of Clyde in Scotland. It is the eighth-longest river in the United Kingdom, and the second-longest in Scotland. Traveling through the major city of Glasgow, it was an important river for shipbuilding and trade in the British Empire. To the Romans, it was Clota,[3] and in the early medieval Cumbric language, it was known as Clud or Clut, and was central to the Kingdom of Strathclyde (Teyrnas Ystrad Clut).

| River Clyde | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) The River Clyde running through the city of Glasgow | |

| Location | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Counties | Argyll, Renfrewshire, Lanarkshire, Dunbartonshire, Inverclyde |

| City | Glasgow |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Lowther Hills in South Lanarkshire |

| • location | South Lanarkshire, Scotland, United Kingdom |

| • coordinates | 55°24′23.8″N 3°39′8.9″W |

| Mouth | Firth of Clyde |

• location | Inverclyde, Scotland, United Kingdom |

• coordinates | 55°40′46.3″N 4°58′16.7″W |

| Length | 170 km (110 mi)[1] |

| Basin size | 4,000 km2 (1,500 sq mi) |

| Basin features | |

| Designation | |

| Official name | Inner Clyde Estuary |

| Designated | 5 September 2000 |

| Reference no. | 1036[2] |

Etymology

The exact etymology of the river is unclear. It is known the name is ancient, and was called Clut or Clud by the Britons and Clota to the Romans. It is likely the name is Celtic in origin then, most likely Old British, however there are several exact roots the river name could come from. One explanation is that it comes from the Common Brittonic Clywwd meaning "loud/loudly".[4] A more likely explanation comes from the hypothesis that the river was named after a local Celtic goddess Clōta, whose name comes from a Proto-Celtic root meaning "the strongly flowing one" or "the holy cleanser". Thus, the river likely means one of these two definitions.

History

Prehistory

The Clyde has been settled on ever since the Paleolithic. Artifacts dated from 12,000 BCE have been found near Biggar, a rural town situated in close proximity to the river. This is one of Britain's oldest archaeological sites.[5] Prehistoric canoes have been found in the river, used by ancient peoples for transport or trade.[6] With the arrival of the Neolithic and Bronze Age, permanent settlements and structures began in the area. An example of these is a supposed temple to moon gods in Govan. Celtic culture and language began spreading from the south at this point and became the dominant culture and art style for prehistoric artifacts around 1000 BCE.

Ancient history

By the time the legions of the Roman Empire had arrived in southern Scotland, the river and surrounding area was held by the Brythonic speaking Damnonii tribe. As no evidence, neither literary or archaeological points to any battles in this land, it is assumed the two groups were on good relations and co-operated in trade and military information. The Romans did however construct several forts (castra) in the area, those notably on the banks of the Clyde include Castledykes, Bothwellhaugh and Old Kilpatrick and Bishopton. The Romans had several roads that ran along the river, including smaller civilian roads and larger main roads designed for trade routes and to carry entire legions. The Antonine Wall lays no more than a few miles from the river, was constructed later on by the Romans as a defensive measure against the Picts. Despite the strategic location and flat land of Glasgow and the surrounding Clyde basin, no Roman civilian settlement was ever constructed, and the region was mostly a frontier zone between Britannia Inferior and the rogue Caledonians. However, a Damnonii town called Cathures is suggested to have been located there as the precursor to modern Glasgow.[7] At some point before 500 AD, (date unknown), the tribe politically unified from individual chiefdoms and formed a centralised kingdom known as Strathclyde.

Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde was formed at some point either during or shortly after the Roman occupation of Britain as an independent British kingdom. The kingdoms core territory and much of the fertile land was around the Clyde basin, with the kingdom being ruled from the "capital", the near impenetrable Alt Clut fortress (Dumbarton Rock), situated on the river and overlooking much of the estuary. This fortress is seemingly noteworthy enough to appear in several letters and poetry about Sub-Roman Britain, especially that by Gildas. Strathclyde remained a powerful kingdom in early medieval Britain and a hold out of native Welsh culture, with their territory expanding along the Clyde Valley, through the Southern Uplands and Ayrshire right down to Cumbria. In the 7th century, Saint Mungo established a new Christian community on the banks of the Clyde, replacing Cathures and beginning the city of Glasgow. Several villages on the Clyde from this time period survive as towns today, including Llanerc (Lanark), Cadzow (Hamilton) and Rhynfrwd (Renfrew). The fortress of Altclut eventually fell in the Siege of Dumbarton of 870 AD, when a force of Norse-Irish raiders from the Kingdom of Dublin sacked the fort. The weakened kingdom moved its capital to Govan although did not recover fully and was annexed by Alba in the 11th century.

Medieval and early modern history

In the 1200s, the still small town of Glasgow gained its first bridge over the river, allowing for its slow growth into a city. The establishment of the University of Glasgow in the 1400s as well as the establishment of the Archdiocese of Glasgow made the town very important in Scotland. From the Early modern period onwards, the Clyde began to be used commercially as trade between Glasgow and the rest of Europe became commonplace. Over the next decades and centuries, the Clyde became vital to Scotland and Britain as a major trading route for exporting and importing resources.

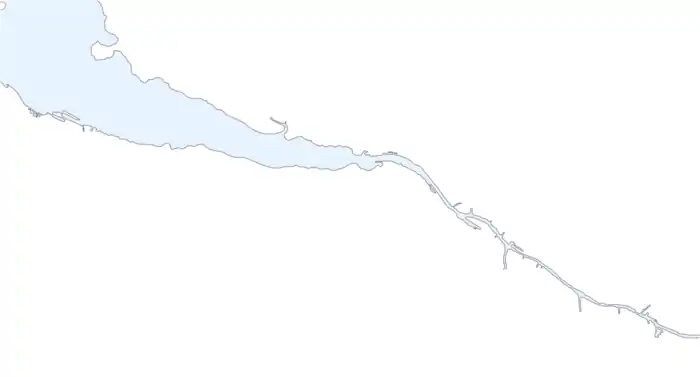

Course

.jpg.webp)

The Clyde is formed by the confluence of two streams, the Daer Water (the headwaters of which are dammed to form the Daer Reservoir) and the Potrail Water. The Southern Upland Way crosses both streams before they meet at Watermeetings (grid reference NS953131) to form the River Clyde proper. At this point, the Clyde is only 10 km (6 mi) from Tweed's Well, the source of the River Tweed, and is a similar distance from Annanhead Hill, the source of the River Annan.[8]

From there, it meanders northeastward before turning to the west, its flood plain used for many major roads in the area, until it reaches the town of Lanark. On the banks of the Clyde, the industrialists David Dale and Robert Owen built their mills and the model settlement of New Lanark. The mills harness the power of the Falls of Clyde, the most spectacular of which is Cora Linn. A hydroelectric power station still generates electricity here, although the mills are now a museum and World Heritage Site.

The river then makes its way north-west, past (although not through) the towns of Wishaw on its eastern side and Larkhall on its western, with the surrounding environment becoming increasingly suburban. Between the towns of Motherwell and Hamilton, the course of the river has been altered to create an artificial loch within Strathclyde Park. Part of the original course can still be seen, and lies between the island and the east shore of the loch. The river then flows through Blantyre and Bothwell, where the ruined Bothwell Castle stands on a defensible promontory.

.jpg.webp)

Past Uddingston and into the southeast of Glasgow, the river begins to widen, meandering a course through Cambuslang, Rutherglen, and Dalmarnock. Flowing past Glasgow Green, from the Tidal Weir westwards the river is tidal, mixing fresh and salt water.[9]

The river is artificially straightened and widened through the city centre, and although the new Clyde Arc now hinders access to the traditional Broomielaw dockland area, seagoing ships can still come upriver following the dredged channel as far as Finnieston, where the PS Waverley docks. From there, it flows past the shipbuilding heartlands, through Govan, Partick, Whiteinch, Scotstoun, and Clydebank, all of which housed major shipyards, of which only two remain.

The river flows out west of Glasgow, past Renfrew, and under the Erskine Bridge past Dumbarton on the north shore to the sandbank at Ardmore Point between Cardross and Helensburgh. Opposite, on the south shore, the river continues past the last Lower Clyde shipyard at Port Glasgow to Greenock, where it reaches the Tail of the Bank as the river merges into the Firth of Clyde. A significant issue of oxygen depletion in the water column has occurred at the mouth of the River Clyde.[10]

The strath of the Clyde was the focus for the G-BASE project from the British Geological Survey in the summer of 2010.

Industrial growth

.jpg.webp)

The success of the Clyde at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution was driven by the location of Glasgow, being a port facing the Americas. Tobacco and cotton trade began the drive in the early 18th century. However, the shallow Clyde was not navigable for the largest ocean-going ships, so cargo had to be transferred at Greenock or Port Glasgow to smaller ships to sail upstream into Glasgow itself.

Deepening the Upper Clyde

In 1768, John Golborne advised the narrowing of the river and the increasing of the scour by the construction of rubble jetties and the dredging of sandbanks and shoals. A particular problem was the division of the river into two shallow channels by the Dumbuck shoal near Dumbarton. After James Watt's report on this in 1769, a jetty was constructed at Longhaugh Point to block off the southern channel. This being insufficient, a training wall called the Lang Dyke was built in 1773 on the Dumbuck shoal to stop water flowing over into the southern channel. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, hundreds of jetties were built out from the banks between Dumbuck and the Broomielaw quay in Glasgow itself. In some cases, this resulted in an immediate deepening as the constrained water flow washed away the river bottom; in others, dredging was required.[11][12]

In the mid-19th century, engineers took on a much greater dredging of the Clyde, removing millions of cubic feet of silt to deepen and widen the channel. The major stumbling block in the project was a massive geological intrusion known as Elderslie Rock.[13] As a result, the work was not completed until the 1880s. At this time, the Clyde also became an important source of inspiration for artists, such as John Atkinson Grimshaw and James Kay,[14] willing to depict the new industrial era and the modern world.

Shipbuilding and marine engineering

The completion of the dredging was well-timed; as steelworking grew in the city, the channel finally became navigable all the way from Greenock to Glasgow. Shipbuilding replaced trade as the major activity on the river, and shipbuilding companies were rapidly establishing themselves on the river. Soon, the Clyde gained a reputation for being the best location for shipbuilding in the British Empire, and grew to become the world's pre-eminent shipbuilding centre. Clydebuilt became an industry benchmark of quality, and the river's shipyards were given contracts for prestigious ocean-going liners, as well as warships, including the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth 2 in later years, all built in the town of Clydebank.

From the founding of the Scott family's shipyard at Greenock in 1712 to the present day, over 25,000 ships have been built on the River Clyde and its Firth and on the tributary River Kelvin and River Cart together with boatyards at Maryhill and Kirkintilloch on the Forth & Clyde Canal and Blackhill on the Monkland Canal. In the same time, an estimated over 300 firms have engaged in shipbuilding on Clydeside, although probably a peak of 30 to 40 at any one time.

The shipbuilding firms became household names on Clydeside, but also known around the world – Denny of Dumbarton, Scott of Greenock, Lithgows of Port Glasgow, Simon and Lobnitz of Renfrew, Alexander Stephen and Sons of Linthouse, Fairfield of Govan, Inglis of Pointhouse, Barclay Curle of Whiteinch, Connell and Yarrow of Scotstoun, to name but a few. Almost as famous were the engineering firms that supplied the machinery to drive these vessels, the boilers and pumps, and steering gear – Rankin & Blackmore, Hastie's and Kincaid's of Greenock, Rowan's of Finnieston, Weir's of Cathcart, Howden's of Tradeston, and Babcock & Wilcox of Renfrew.

One 'Clyde' shipyard was not even located on one of these waterways: Alley & MacLellan's Sentinel Works in Jessie Street at Polmadie is around half a mile from the Clyde, yet it is reputed to have constructed over 500 vessels, many of which were assembled then 'knocked down' to kit form for despatch to some far distant and remote location – one such vessel being the SS Chauncy Maples, still in service on Lake Malawi. Clyde shipbuilding reached its peak in the years just before World War I, and over 370 ships were thought to have been completed in 1913.

Yachting and yachtbuilding

The first recorded Clyde racing yacht, a 46-ton cutter, was built by Scotts of Greenock in 1803, and the great Scottish yacht designer William Fyfe did not start designing yachts until 1807. The first yacht club on the Clyde was the Northern Yacht Club, which appeared in 1824 and received its Royal Charter in 1831. The club was founded to organise and encourage the sport, and by 1825, Scottish and Irish clubs were racing against each other on the Clyde. However, yachting and yacht building did not really take off until the middle of the 19th century.

The Clyde became famous worldwide for its significant contribution to yachting and yachtbuilding, and was the home of many notable designers: William Fife III, Alfred Mylne, G. L. Watson, E. McGruer, and David Boyd. It was also the home of many famous yacht yards.

Robertson's Yard started repairing boats in a small workshop at Sandbank in 1876, and went on to become one of the foremost wooden boat builders on the Clyde. The 'golden years' of Robertson's yard were in the early 20th century, when they started building classic 12-and-15-metre (39 and 49 ft) racing yachts. More than 55 boats were built by Robertson's in preparation for the First World War, and the yard remained busy even during the Great Depression in the 1930s, as many wealthy businessmen developed a passion for yacht racing on the Clyde. During World War II, the yard was devoted to Admiralty work, producing large, high-speed Fairmile Marine motor boats (motor torpedo boats and motor gun boats). After the war, the yard built the successful one-class Loch Longs and two David Boyd-designed 12 m (39 ft) challengers for the America's Cup: Sceptre (1958)[15] and Sovereign (1964). Due to difficult business conditions in 1965, the yard was turned over to GRP production work (mainly Pipers and Etchells) until it closed in 1980. During its 104-year history, Robertson's Yard built 500 boats, many of which are still sailing today.

Other notable boatyards on the Clyde, both situated on the Rosneath peninsula on the banks of the Gare Loch within half a mile of each other, were Silvers (1910-1970) and McGruers (1910-1973). Both yards built many well-known and classic yachts, some of which are still sailing today. McGruers built over 700 boats but both yards are no longer in business as boatbuilders.[16][17][18]

Glasgow Humane Society

The Glasgow Humane Society is the oldest lifesaving organisation in the world, founded in 1790 and has been responsible for the safety and preservation of life on Glasgow's waterways.

Shipbuilding decline

The downfall of the Clyde as a major industrial centre came during and after World War II. Clydebank in particular was targeted by the Luftwaffe and sustained heavy damage. The immediate postwar period had a severe reduction in warship orders, which was balanced by a prolonged boom in merchant shipbuilding. By the end of the 1950s, however, the rise of other shipbuilding nations, recapitalised and highly productive, made many European yards uncompetitive. Several Clydeside yards booked a series of loss-making contracts in the hope of weathering the storm. However, by the mid-1960s, shipbuilding on the Clyde was becoming increasingly uneconomical and potentially faced collapse.[19] This culminated in the closure of Harland and Wolff's Linthouse yard and a bankruptcy crisis facing Fairfields of Govan. The government responded by creating the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders consortium. After the consortium's controversial collapse in 1971, the Labour government of James Callaghan later passed the Aircraft and Shipbuilding Industries Act, which nationalised most of the Clyde's shipyards and grouped them with other major British shipyards such as British Shipbuilders.

Today, two major shipyards remain in operation on the Upper Clyde; they are owned by a naval defence contractor, BAE Systems Surface Ships, which specialises in the design and construction of technologically advanced warships for the Royal Navy and other navies around the world. The two yards are the former Yarrow yard at Scotstoun and Fairfields at Govan. Also, the King George V Dock is operated by the Clyde Port Authority. On the Lower Clyde, the Scottish Government owned Ferguson Shipbuilders at Port Glasgow is the last survivor of the many shipyards that once dominated Port Glasgow and Greenock – its mainstay being the construction of car ferries.

Regeneration

The Clyde Waterfront Regeneration project is expected to attract investment of up to £5.6bn in the area from Glasgow Green to Dumbarton. Market gardens and garden centres have grown up on the fertile plains of the Clyde Valley. Tourism has also brought many back to the riverside, especially in Glasgow, where former docklands have given way to housing and amenities on the banks in the city, for instance, the Glasgow Harbour project, the Glasgow Science Centre, and the creation of the Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre. With the migration of the commercial Port of Glasgow downstream to the deeper waters of the Firth of Clyde, the river has been extensively cleaned up, once having a very poor reputation for pollution and sewage, to make it suitable for recreational use.

The Clyde Walkway is a foot and mountain bike path that follows the course of the Clyde between Glasgow and New Lanark. It was completed in 2005, and is now designated as one of Scotland's Great Trails by Scottish Natural Heritage.[20]

Pollution

Organic chemical pollution contained in sediments of the Clyde estuary have been evaluated by British Geological Survey.[21][22][23] Surface sediments from the Glasgow reaches of the Clyde, Cunningar to Milton, contained polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) from 630 µg/kg to 23,711 µg/kg and polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) in the range of 5 to 130.5 µg/kg, which classifies these sediments as non-toxic.[21] However, a later study showed PCB concentrations as high as 5,797 µg/kg, which is above published threshold levels for the chlorinated compounds.[22] Comparison of individual PAH compounds with different thermal stabilities shows that the source of PAH pollution in the Clyde changes downriver. PAH in the inner Clyde (Cunningar to Milton) are from combustion sources (vehicle exhaust, coal burning), whereas PAH in the outer Clyde are from petroleum spills[21][22]

The amount and type of sedimentary pollution contained in the Clyde is closely related to the area's industrial history.[22] Assessment of the changing type of pollution through time (1750 to 2002) has been gained through the collection of seven sediment cores of one metre's depth which were dated using lead concentrations and changing lead isotope ratios. The sediments showed a long but declining history of coal usage and an increasing reliance on petroleum fuels from about the 1950s. Thereafter, declining hydrocarbon pollution was followed by the onset (1950s), peak (1965–1977), and decline (after 1980s) in total PCB concentrations.[22]

Although pollution from heavy industry and power generation is falling, evidence indicates that man-made pollution from new synthetic compounds in electrical products and textiles is on the increase.[23] The amounts of 16 polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) compounds used as flame retardants in televisions, computers, and furniture upholstery were measured in sediment cores collected from six sites between Princes Dock and Greenock. Comparison of the amounts of PBDE compounds revealed a decline in certain compounds in line with the European ban on production of mixtures containing environmentally harmful PBDE with eight and nine bromine atoms and a rise in the less harmful mixture composed of ten bromine atoms.[23]

Media

The Clyde is central to the Para Handy novels of Neil Munro, and subsequent adaptations, and features in novels by Alasdair Gray, Matthew Fitt, and Robin Jenkins. It appears in the "Ossian" poetry of James Macpherson, as well as the works of John Wilson, William McGonagall, Edwin Morgan, Norman McCaig, Douglas Dunn and W.S. Graham. It features in artworks by, amongst others, William McTaggart, J.M.W. Turner, Robert Salmon, John Atkinson Grimshaw, Stanley Spencer, and George Wyllie.

The Clyde appears prominently in the films Young Adam, Sweet Sixteen, Just a Boys' Game, and Down Where the Buffalo Go, and was the subject of the Academy Award-winning film documentary Seawards the Great Ships. It is referenced in the traditional folk songs "Clyde's Water" and "Black Is the Color (of My True Love's Hair)", as well as "Song of the Clyde", popularised by Kenneth McKellar.

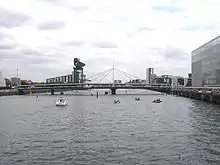

Bells Bridge

Bells Bridge Millennium Bridge

Millennium Bridge Modern buildings, including the Clyde Auditorium, Finnieston Crane, Crowne Plaza Hotel and the SSE Hydro

Modern buildings, including the Clyde Auditorium, Finnieston Crane, Crowne Plaza Hotel and the SSE Hydro The estuary opens out past Dumbarton.

The estuary opens out past Dumbarton. Looking across to Dumbarton at low tide

Looking across to Dumbarton at low tide Looking east toward Glasgow's CBD

Looking east toward Glasgow's CBD South-facing view of the Tradeston bridge

South-facing view of the Tradeston bridge Aerial view looking downstream along the River Clyde to the Erskine Bridge, the Firth of Clyde and the Argyll hills

Aerial view looking downstream along the River Clyde to the Erskine Bridge, the Firth of Clyde and the Argyll hills

Heat Pumps

The River Clyde, or more accurately the Clyde Estuary, has a significant capacity as a heat source. The flow rate downstream alone is around 50 m3/s.[24] If this was cooled by 3 °C this would allow for 188.1 MW of heat extraction from river heat pumps. River heat pumps typically have an efficiency of 3.0 so the heat deliverable is 1.5 times the river component so 282 MW of heat could be delivered. Typical temperatures for industrial heat pump deliver are 80 °C.

In 2020, West Dunbartonshire Council completed the deployment of a river source heat pump scheme (the first large one in Britain delivering at 80 °C). The project was delivered by Vital Energi with heat pumps supplied by Star Refrigeration Ltd who manufactured them in their Glasgow factory. The development area is called Queens Quay.

See also

References

- "River Clyde". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Inner Clyde Estuary". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "TM Places". www.trismegistos.org.

- "What does the name 'Clyde' mean?". Answers.com. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- "Scotland's oldest home found at 14,000 years old". The Scotsman.

- "The Glasgow Story". 21 December 2020.

- "The British Damnonii Tribe". 22 December 2020.

- The Tweed: Take a trip on a river flowing with history, The Independent, 21 April 2007

- "Tidal Weir". Glasgow City Council. 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- C.Michael Hogan. 2011. Irish Sea. eds. P.Saundry & C.Cleveland. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

- Riddell, John F (1999). "Improving the Clyde: the eighteenth century phase". In Goodman, David (ed.). The European Cities and Technology Reader. London: Routledge in association with the Open University. pp. 57–63. ISBN 0-415-20082-2.

- "Making the Clyde". Best Laid Schemes. Archived from the original on 18 January 2006. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- "Removal of Elderslie Rock". The Glasgow Herald. 11 March 1886. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- Macmillan, Duncan (1994). Scottish Art in the 20th Century. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. pp. 31–32. ISBN 1-85158-630-X.

- "Sceptre". britishclassicyachtclub.org. Archived from the original on 14 April 2005. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- "A brief history of Silvers Marine". Silvers marine.

- "Register of Scottish-built ships". Clydeships.co.uk.

- "Colourful history of McGruers". Helensburgh heritage.

- Harris, Hilary. "Seaward the Great Ships". Moving Image Archive. National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "Trails". Scotland's Great Trails. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- Vane, C.H., Harrison, I., Kim, A.W. (2007). "Assessment of Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) in surface sediments of the Inner Clyde Estuary, U.K." Marine Pollution Bulletin. 54: 1301–1306. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2007.04.005.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Vane, C.H., Chenery, S.R., Harrison, I., Kim, A.W., Moss-Hayes, V., Jones, D.G (2011). "Chemical Signatures of the Anthropocene in the Clyde Estuary, UK: Sediment hosted Pb, 207/206Pb, Polyaromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) and Polychlorinated Biphenyl (PCB) Pollution Records" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 369: 1085–111. doi:10.1098/rsta.2010.0298. PMID 21282161.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Vane, C.H., Yun-Juan Ma, She-Jun Chen and Bi-Xian Mai. (2010). "Inventory of Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in sediments of the Clyde Estuary, U.K." Environmental Geochemistry & Health.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "NRFA Station Mean Flow Data for 84013 - Clyde at Daldowie".

Further reading

- Millar, William John. The Clyde: from its source to the sea, its development as a navigable river.... (1888)

- Shields, John. Clyde built: a history of ship-building on the River Clyde (1949)

- Walker, Fred M. Song of the Clyde: a history of Clyde shipbuilding (1984), 233 pages

- Williamson, James. The Clyde passenger steamer (1904) full text

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to River Clyde. |

- River Clyde: Source to Firth Panorama Project

- The data base of ships built on the Clyde and in the rest of Scotland – lists over 22,000 ships built on the Clyde

- Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection on loan to Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Shipping on the Clyde in Glasgow from Grimshaw, on Flickr.com

- Clyde Waterfront regeneration

- Clyde Waterfront Heritage

- River Clyde waterfront regeneration

- Gallery of pictures of the River Clyde from the Erskine Bridge

- Glasgow Digital Library: Glimpses of old Glasgow

- In Glasgow Photo Gallery of pictures of the River Clyde

- Clydebank Restoration Trust – Pictures and history

- Clyde Bridges Heritage Trail

- Clydebank Restoration Trust

- Video footage and history of Bodinbo or Bottombow Island at Erskine