Robertson Tunnel

The Robertson Tunnel is a twin-bore light rail tunnel through the Tualatin Mountains west of Portland, Oregon, United States, used by the MAX Blue and Red Lines. The tunnel is 2.9 miles (4.7 kilometers) long[1] and consists of twin 21-foot-diameter (6.4 m) tunnels. There is one station within the tunnel at Washington Park, which at 259 feet (79 m) deep is the deepest subway station in the United States and the fifth-deepest in the world.[5] Trains are in the tunnel for about 5 minutes, which includes a stop at the Washington Park station. The tunnel has won several worldwide engineering and environmental awards.[6] It was placed into service September 12, 1998.[7]

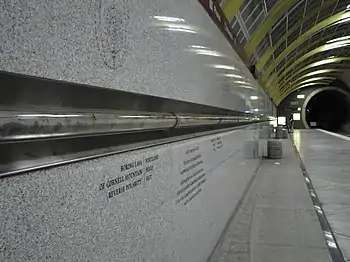

East portal of the tunnel in 2007 | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Line | |

| Location | Tualatin Mountains, Portland, Oregon, United States 45.510661°N 122.716869°W |

| Status | Operational |

| System | MAX Light Rail |

| Start | Goose Hollow 45.519087°N 122.699749°W |

| End | Sunset Hills Mortuary 45.506324°N 122.753833°W |

| No. of stations | 1 |

| Operation | |

| Opened | September 12, 1998 |

| Owner | TriMet |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 2.93 miles (4.71 km) (15,450 feet)[1] |

| No. of tracks | 2 (double track) |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in)[2] |

| Electrified | 750 Vdc, overhead[3] |

| Operating speed | 55 mph (90 km/h) |

| Highest elevation | 605 feet (184 m) approx. 6,000 feet (1,800 m) inside west portal[4] |

| Lowest elevation | 220 feet (67 m) at east portal[4] |

The tunnels pass through basalt layers up to 16 million years old. Due to variations in the rock composition, the tunnel curves mildly side to side and up and down to follow the best rock construction conditions.[8] The tunnels vary from 80 to 300 feet (24–91 m) below the surface. A core sample taken during construction is on display with a timeline of local geologic history.[9] The east tunnel entrance is near Vista Bridge at the edge of the Goose Hollow neighborhood at the foot of Washington Park. The west entrance is along U.S. Highway 26 just west of the Finley-Sunset Hills cemetery, about a mile east of the junction with Oregon Highway 217.[10]

Name

The tunnel is named for William D. Robertson, who served on the TriMet board of directors and was its president at the time of his death.

History

Plans to build a light rail line to serve Portland's western suburbs in Washington County emerged in 1979 with a Metro regional government proposal to extend what would become the Metropolitan Area Express (MAX) from its inaugural terminus in downtown Portland father west to the cities of Beaverton and Hillsboro. During early planning, several alternative alignments through the West Hills were determined, including routes along the Sunset Highway, Beaverton–Hillsdale Highway, and Multnomah Boulevard.[11]:2–4[12] A majority of jurisdictions had selected a Sunset Highway light rail alternative by June 1982,[13] with the Portland City Council the last to adopt a resolution supporting this route in July 1983.[14] Metro subsequently moved forward with this alternative, and the Urban Mass Transportation Administration (UMTA) authorized $1.3 million in funds to begin a preliminary engineering study.[15]:P-1 Soon afterwards, TriMet suspended the project to focus on the completion of the first MAX segment.[16]

Planning for the westside extension resumed in January 1988.[15]:P-1[17] Prior to the start of preliminary engineering efforts, the Portland City Council asked TriMet to consider building a rail tunnel through the West Hills instead of following the Sunset Highway alternative's proposal to run tracks on the surface alongside Canyon Road. TriMet's engineers noted that this surface option would carry a steep six- to seven-percent grade as opposed to only two percent in a tunnel.[18] That May, TriMet awarded a $230,000 contract to surveying firm Spencer B. Gross of Portland to map out the proposed area and another $200,000 contract to a partnership between Cornforth Consultants of Tigard and tunneling firm Law/Geoconsult International International of Atlanta to determine alternative tunnel routes.[19] After several months of soil testing, TriMet announced that a tunnel would be feasible.[20] In October, the agency released a report that identified three tunnel options: a 3-mile (4.8 km) "long tunnel" with a station serving the Oregon Zoo, the same long tunnel without a station, and a .5-mile (0.80 km) "short tunnel". Both long tunnels featured a western portal west of Sylvan while the short tunnel featured one on Canyon Road, and all three had an eastern portal near Jefferson Street in Portland's Goose Hollow neighborhood.[21] These proposals were immediately met with opposition from West Hills residents who feared that tunneling activity would trigger landslides.[22]

Several alternative alignments through the West Hills were studied, including an all-surface option along the Sunset Highway (U.S. 26), an option with a half-mile-long (0.8 km) "short tunnel", and an option with a three-mile (4.8 km) "long tunnel".[23][24] TriMet selected the "long tunnel" in April 1991.[25]

Construction began in the summer of 1993 at the west end, employing the conventional mining technique of drilling and blasting due to the loose mixture of materials. More than 75 tons of explosives were used and mining progressed about a mile into the hill. East end construction began in August 1994 with a customized tunnel boring machine. About a thousand workers from 230 construction firms were involved in the 18-mile westside MAX line, including those who built the tunnel and installed the reinforced concrete liner, tracks and wiring. One worker was killed while operating equipment.[10]

Tunnel construction continued 24 hours a day, six days per week. The north tunnelers met after 16 months on December 29, 1995, and the boring machine began the south tunnel in April 1996. Work in the south tunnel took only four months before the tunneling teams met on August 15, 1996.[10]

To complete the west end at the cemetery, 14 bodies were relocated.[10]

The original estimate for the tunnel was $103.7 million, but the final price tag came to $184 million, largely due to challenges posed by unexpected loose layers of silt and gravel, and crumbling basalt which prevented the boring machine from working effectively.[10]

Route

The tunnel generally follows – but remains north of – U.S. Highway 26, diverging the most (1⁄3 mile (540 meters)) in the Oregon Zoo area.

The elevation at the west end is higher than the east but there is very little perceptible slope except for several gentle, short grades which exist presumably to follow the easiest-to-bore rock stratum.

During construction, the east portal was west of Canyon Road, below City of Portland Reservoir 4. After completion, the road was raised and an overpass placed over the track. This effectively extended the original bored-and-blasted tunnel east by about 430 feet (130 m), making the final length 2.93 miles (4.71 km),[1] so that it would emerge to the east of Canyon Road, and on the south side of Jefferson Street (immediately east of where Canyon Road bends from north to east and becomes Jefferson Street).

Beginning at the east end (traveling westward), under Canyon Road the tunnel turns SSW (202°)[26] for about 300 m (980 ft) where it turns WSW (236°) under the large field east of the Elephant House. Twelve hundred meters (4000 ft) later it is directly under and follows SW Kingston Road at a point 250 m (820 ft) north of the zoo's elephant exhibit. For the next 250 m (820 ft), it arcs until almost directly westward (263°) and straightens for 300 m (980 ft) to arrive at Washington Park.

After the station, it passes under the south side of the World Forestry Center's main building and turns 4° northward (267°) and continues for its longest straight stretch of 900 meters (3,000 ft). At the point it passes under SW Skyline Road 150 meters (490 ft) north of the Sylvan Bridge, it turns slightly southward (253°) and—300 m (980 ft) later—goes under the Finley-Sunset Hills building and water feature. For the remaining 500 m (1,600 ft)), it turns right in a long gradual arc exactly paralleling Sunset Hwy. The arc continues at the same rate after the west portals, and is due west (270°) about 500 m (1,600 ft) past the portals.

References

- Light Rail and Modern Tramway, November 1993, p. 302. UK: Ian Allan Publishing/Light Rail Transit Association.

- Mark Kavanagh. "Portland Transit—MAX Light Rail". Kavanagh Transit Systems. Archived from the original on 2007-03-29. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- Kinh D. Pham; Ralph S. Thomas; Xavier Ramirez. "Traction Power Supply for the Portland Interstate MAX Light Rail Extension" (PDF). Transportation Research Board. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- Trimet Capital Projects and Facilities Division (August 2011). "TriMet Portland to Milwaukie LRT Type 5 LRV, Contract No. RH120160BW Reference Drawings, Request for Proposal" (PDF). pp. 7–8.

- "The world's deepest subway stations". The Moscow News. 1 December 2012. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 2013-03-20.

- "Awards & Recognition". TriMet. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- "Westside MAX Blue Line Project History". TriMet. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- "Westside light rail—the MAX Blue Line extension" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- "Portland MAX: East-West MAX (Blue)". world.nycsubway.org. Archived from the original on 2007-02-12. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- Sam's. "Tunneling and Civil Engineering". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- Westside Corridor Project Draft Environmental Impact Statement Alternatives Analysis (Report). Urban Mass Transportation Administration, United States Department of Transportation. March 1982. Retrieved December 14, 2020 – via Google Books.

- Federman, Stan (May 23, 1982). "Public gets chance to contribute to transportation planning". The Sunday Oregonian. p. B4. Retrieved December 15, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Heinz, Spencer (July 11, 1983). "Sunset light-rail project at city crossroads". The Oregonian. p. B1. Retrieved December 15, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Heinz, Spencer (July 13, 1983). "Council leans to Sunset light-rail plan". The Oregonian. p. B1. Retrieved December 15, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Hillsboro Corridor Alternatives Analysis Draft Environmental Impact Statement (Report). Federal Transit Administration, United States Department of Transportation. April 1993. Retrieved December 16, 2020 – via Google Books.

- "Westside MAX Blue Line Extension" (PDF). TriMet. July 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- Federman, Stan (November 7, 1987). "Tri-Met heats up study for westside light rail". The Oregonian. p. E14. Retrieved December 16, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Federman, Stan (January 21, 1988). "West side light rail seen years away". The Oregonian. p. C8. Retrieved December 16, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Federman, Stan (May 5, 1988). "Tri-Met studies westside tunnel". The Oregonian. p. C4. Retrieved December 16, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Federman, Stan (September 15, 1988). "Tests find rail tunnel feasible". The Oregonian. p. C2. Retrieved December 16, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Federman, Stan (October 27, 1988). "Light-rail tunnel called feasible". The Oregonian. p. A1. Retrieved December 16, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Federman, Stan (October 31, 1988). "West Hills groups split on light-rail tunnel". The Oregonian. p. D13. Retrieved December 16, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Kirchmeier, Mark (January 27, 1989). "Tri-Met picks Goose Hollow for MAX route". The Oregonian. p. E4.

- Mayer, James (January 25, 1990). "Revised westside light-rail options run to $496 million". The Oregonian. p. C3.

- Mayer, James (April 13, 1991). "Board picks light-rail tunnel". The Oregonian. p. 1.

- The tunnel was tracked on TopoZone data on ACME Mapper. The angle was measured using Photoshop. The angles are expressed in conventional navigational cardinal direction values.