Rugby union in Wales

Rugby union in Wales is the national sport and is considered a large part of national culture. Rugby union is thought to have reached Wales in the 1850s, with the national body, the Welsh Rugby Union (WRU) being formed in 1881.[2] Wales are considered to be one of the most successful national sides in Rugby Union, having won the most Six Nations Championships, as well as having reached 3 World Cup semi finals in 1987, 2011 and 2019, having finished 3rd in the inaugural competition and having finished 4th in 2011 in a repeat of the first third place play-off. The Welsh team of the 1970s is considered to be arguably the greatest national team of all time, prompting many experts in the game to suggest that had the Rugby World Cup existed during this period, Wales would be amongst the list of World Cup winners. Following their fourth-place finish in the latest World Cup, they are ranked 4th in the world, behind England but ahead of Ireland.

| Rugby union in Wales | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | Wales |

| Governing body | Welsh Rugby Union |

| National team(s) | Wales |

| Registered players | 79,800 [1] |

National competitions | |

Club competitions | |

The national team play at the WRU-owned Principality Stadium, and compete annually in the Six Nations Championship, as well as having competed at every Rugby World Cup. Wales are ranked as a tier-1 nation by World Rugby (WR). Wales also competes as one of the 15 "core teams" in the annual World Rugby Sevens Series, and won the 2009 Rugby World Cup Sevens.

The main domestic competition in Wales is the Pro14 (historically the Celtic League), in which Wales have four regional sides in the competition which is also contested by Irish and Scottish clubs and from 2010-11 Italian teams. Top-level Welsh regional teams (Ospreys, Cardiff Blues, Scarlets and Dragons) also compete in the Europe-wide European Rugby Champions Cup and European Rugby Challenge Cup and alongside the teams of England's Premiership in the Anglo-Welsh Cup.

Beneath the Pro14, club rugby is represented by over 200 WRU affiliated clubs who play in the Welsh Premier Division and the lower Welsh Divisional leagues. Historically the four major Welsh club teams that have shaped the Welsh national team have been Cardiff, Newport, Swansea and Llanelli, though other clubs which have fought for prominence and provided national sporting heroes during the last 120 years include Bridgend, Neath, Pontypool, Pontypridd, and England exiles London Welsh. Four Welsh teams compete in the British and Irish Cup, a competition for semi-professional and developmental sides from Great Britain and Ireland. They are usually the top Premier Division clubs of each region, although the reserve sides of the Pro12 teams were entered in 2015-16.

As of February 2019 the Welsh Rugby Union are reviewing the number of regions, with potential consolidation for funding two or three super teams.

History

The growth of rugby in Wales 1850-1900

Rugby-like games have a long history in Wales, with games such as cnapan being played for centuries.[3] Rugby seems to have reached Wales in 1850, when the Reverend Professor Rowland Williams brought the game with him from Cambridge to St. David's College, Lampeter,[4] which fielded the first Welsh rugby team that same year.

Rugby initially expanded in Wales through ex-pupils of the Welsh colleges settling, or students from English colleges and universities returning to the larger industrial hubs of South Wales. This is reflected in the first clubs to embrace the sport in the early to mid-1870s, with Neath RFC widely recognised as the first Welsh club. The strength of Welsh rugby developed over the following years, which could be attributed to the 'big four' South Wales clubs of Newport (who lost only seven games under the captaincy of Llewellyn Lloyd between the 1900/01 and 1902/03 seasons[5]), Cardiff, Llanelli (who lost just twice in 1894 and 1895) and Swansea. With the coming of industrialisation and the railways, rugby too was spread as workers from the main cities brought the game to the new steel and coal towns of south Wales. Merthyr formed in 1876, Brecon in 1874, Penygraig in 1877; as the towns adopted the new sport they reflected the growth and expansion of a new industrial Wales.[6]

In the 19th century as well as the established clubs there were many 'scratch' teams populating most towns, informal pub or social teams that would form and disband quickly. Llanelli, as an example, in the 1880s was home not only to Llanelli RFC, but also to Gower Road, Seasiders, Morfa Rangers, Prospect Place Rovers, Wern Foundry, Cooper Mills Rangers, New Dock Strollers, Vauxhall Juniors, Moonlight Rovers and Gilbert Street Rovers.[7] These teams would come and go, but some would merge into more settled clubs which exist today, Cardiff RFC was itself formed from three teams, Glamorgan, Tredegarville and Wanderers Football Clubs.

The South Wales Football Club was established in 1875[8] to try to incorporate a standard set of rules and expand the sport and this was succeeded by the Welsh Football Union which was formed in 1881.[9] With the forming of the WFU (which would become the Welsh Rugby Union in 1934), Wales began competing in recognised international matches, with the first game, against England, also in 1881.[10] The first Welsh team although fairly diverse in the geography of the clubs represented, did not appear to truly represent the strength available to Wales. The team was mainly made up of ex-Cambridge and Oxford university graduates and the selection was heavily criticised in the local press after the crushing defeat by England.[9]

By the end of the 19th century, a group of exciting Welsh players began to emerge, including Arthur Gould, Billy Bancroft and Gwyn Nicholls; players that would be regarded as the first super-stars of Welsh rugby and would usher in not only the first golden era of Welsh rugby, but would also see the introduction of specialised positional players.

The first golden era 1900-1919

The first 'Golden Era' of Welsh rugby is so called due to the success achieved by the national team during the early 20th century. Wales had already won the Triple Crown in 1893, but between 1900 and 1914 the team would win the trophy on six occasions, and with France joining the tournament (unofficially in 1908 and 1909) three Grand Slams.[11]

With the introduction of specialised players like hooker George Travers,[12] the WFU could no longer choose the 'best players' to represent Wales, they needed to think tactically and choose people who could do a specific job on the pitch. This period of Welsh rugby would see the grip of the 'Big Four' clubs providing the bulk of national players, slip slightly. The WFU still tended to turn to the likes of Swansea and Newport to supply the skillful back players and usually kept club half-back pairings together such as Jones and Owen of Swansea. But it was the introduction of the 'Rhondda Forward' which saw men who worked day in day out in the coal, iron and tin mines enter the Welsh front row.[13] Chosen for their strength and aggressive tackling, players such as Dai 'Tarw' Jones from Treherbert and Dai Evans from Penygraig added muscle to the front row.

Although a progressive time for international rugby, this period initially saw regression for many of the club sides in the form of the temperance movement. In the early 1900s, rugby was seen as a wicked temptation to the young men of the mining and steel communities, leading to violence and drink,[14] and the valley areas in particular were part of a strong Nonconformist Baptist movement. The religious revival saw some communities completely reject rugby and local clubs, like Senghenydd, disbanded for several years. It wasn't until the 1910s that the social view of rugby would change the other way, fostered by mine owners as a great social unifier;[15] and like baseball in America would be portrayed as a '...source of community integration because it installed civic pride'.[16]

Unlike the game in England, rugby union in Wales was never seen as a sport for gentlemen of higher learning. Although this was fostered in the first international Welsh team, the fast absorption of the sport into the working class areas appeared to sever the link of rugby as a sport for the middle and upper classes.[17]

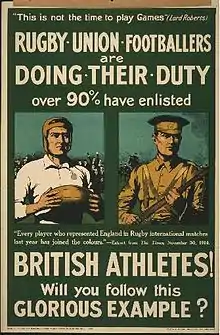

As rugby became linked with the hard working men of the industrialised areas of Wales, it should also be noted that the sport did not escape the hardships of the industries. In 1913 five members of the Senghenydd team were killed in Britain's worst colliery disaster and many more lost their lives in the 'slow drip' of deaths caused by the industries. Far worse was to follow during the conflict of World War I when many teams lost members, including Welsh internationals like Charlie Pritchard[18] and Johnnie Williams.[19]

Post-war Welsh rugby 1920-1930

The 1920s were a difficult time for Welsh rugby. The first golden period was over and the players that made up the teams that won four Triple Crowns had already disbanded before the Great War. The war could not be blamed for the downturn in Welsh fortunes as all the home nations lost their young talent in equal numbers. The fact that so many of Wales' talented stars had retired from rugby before 1910 was felt when Wales failed to win the tournament in the few years leading up to the war. But the main reason for Welsh failure on the rugby pitch can be mapped to an economic failures of Wales as a country. The First World War had created an unrealistic demand for coal, and in the 1920s the collapse in the need for coal resulted in a massive level of unemployment throughout the south Wales valleys.[20] This in turn led to mass emigration as people left Wales for work. The knock-on effect was felt in the port cities of Newport and Cardiff, that relied on the transportation of coal.

Suddenly the call of the professional league was a very strong draw to men who could not claim money for playing union. Between 1919 and 1939, Forty-eight capped Welsh rugby union players joined league rugby.[21] The fact that the equivalent of three full national squads left the sport can only allude to the number of trialists and club members that also left the sport. Exceptional players lost to the league game included Jim Sullivan of Cardiff, William Absalom of Abercarn and Emlyn Jenkins of Treorchy.[21]

The other side of the depression was linked to those people that stayed behind. In homes where men were the only earners, the decline in heavy labour areas resulted in very stark choices in where the household money could be spent. It was difficult to justify paying to watch rugby when there was little money for food and rent. With crowds dwindling clubs were forced to drastic measures in the hope of survival. Loughor which had produced five internationals in the 1920s were by 1929 begging door to door for old kit.[22] Haverfordwest disbanded from 1926–29, Pembroke Dock Quins were reduced to 5 members by 1927 and in the valleys the Treherbert, Llwynypia and Nantyffyllon clubs had vanished before 1930.[22][23] Even clubs of the size of Pontypool were not spared; in 1927 they were playing and beating the Waratahs and the Maoris, by 1930 they were £2,000 in debt and facing bankruptcy.[24]

Another reason for the fall in the Welsh union game can be placed on the improvement of football in Wales.[25] Traditionally seen as a game more associated with North Wales, the success of Cardiff Football Club in the 1920s was a strong draw for many supporters. With two F.A. Cup Finals in 1925 and 1927, Cardiff were making the once unpopular sport of 'soccer' very fashionable, for fans and sportsmen alike.[20]

During the 1920s the one team that appeared to be unaffected by the double threat of soccer and debt was Llanelli.[26] The Scarlets had an unswerving loyalty shown by their home supporters, who were repaid by exciting, high scoring matches.[26] During the 1925/26 season the club were unbeaten and the next season they had achieved the feat of defeating Cardiff on four occasions. This success would later be reflected in the growing number of Llanelli players that would represent their country in the 1920s,[27] including Albert Jenkins, Ivor Jones and Archie Skym.

Apart from a few sporadic victories from the national team, there appeared little to cheer about in the 1920s for Welsh rugby at club or country level; but the seeds of recovery were being planted during the same decade. On June 9, 1923 the Welsh Secondary Schools Rugby Union was established in Cardiff.[28] Founded by Dr R Chalke, head of Porth Secondary School with WRU members Horace Lyne as president and Eric Evans as secretary.[28] Its aim was to promote rugby at school level in an attempt to regain 'the glorious days of Gwyn Nicholls, Willie Llewellyn and Dr E.T. Morgan'. In April 1923, at the Arms Park, Wales played their first secondary schools fixture led by future international Watcyn Thomas, who would progress to captain the first Welsh University XV in 1926.[29] Over the coming years, schools such as Cardiff High School, Llanelli County School, Llandovery and Christ College, Brecon fostered a generation of players which would fill the Welsh ranks over the coming years. Wales had in effect begun to mimic the systems adopted by England and Scotland, that rugby should be nurtured from youth, through adolescence to adulthood.[30]

The 1920s closed with the formation of the West Wales Rugby Union, an event that initially appeared to be a positive indication of growth, but in fact the union was formed by western clubs to wrest control away from the WRU. The West Wales clubs had become disenchanted in decisions made by their parent body and believed the Union had no interest in the lower tier clubs, allowing them to become mere feeders for the bigger clubs.[31]

The Welsh revival 1930-1939

The 1930s began on a high for Welsh international rugby, with success in the Home Nations Championship and the emergence of a strong Welsh team. In the 1931 Championship Wales beat Ireland at Ravenhill in a bruising affair that not only gave Wales the title but denied Ireland the Triple Crown. This may have signaled a change in fortunes in Welsh rugby but underneath the same problems that dogged Wales throughout the 1920s still remained. Wales was still suffering the effects of the depression and club rugby was struggling to survive.[32] Even the WRU had problems, as it faced the fact that it was the only home union without their own ground. The Cardiff Arms was leased and St Helens was on loan.[33]

From what at first appears to be yet another decade of turmoil for Welsh rugby, is actually regarded as a period of revival. The economic situation began turning from 1937, the WSSRU was bringing many exciting backs through the school system, North Wales embraced the game and the national team won two morale lifting games against England in 1933 and the All Blacks in 1935.

From a statistical point of view, the Welsh national team appeared to be winning roughly the same number of games throughout the 1930s as the poor 1920s period, but Wales were actually improving. In the 1920s most Welsh victories were against France, then the weakest team in the Five Nations Championship; but in 1931 France were excluded from the tournament over accusations of professionalism at club level and were not readmitted until after the 1939 tournament, just before international rugby was suspended because of the Second World War. Welsh victories were now coming against the more established home nation teams. During this period, Wales won three Championships, but its greatest victory happened during the 1933 tournament when they finished last. Since its first international game in 1910, Wales had failed to beat England at Twickenham in nine attempts. Now dubbed the 'Twickenham bogey', it took the self confidence of Cardiff's Ronnie Boon to break the losing streak as he scored a try and a drop goal to take the match 7-3. The game also saw the debut of two players who would become Welsh greats, Wilf Wooller and Vivian Jenkins.

Wales played host to two touring Southern Hemisphere teams in the 1930s, first came Bennie Osler's South Africa followed by Jack Manchester's All Blacks. The South Africans were rampant in Wales, winning the test match and all six club matches, though gained few supporters due to the kicking tactics Osler employed. The New Zealander's received a better welcome, and after the previous tour where the tourist went unbeaten the Welsh press were hoping for a return of the spirit that won the first encounter in 1905. Before the match with Wales, New Zealand were to face eight club teams over six games. After winning the opening three English county matches and then beating a joint Abertillery and Cross Keys the All Blacks were showing the same form shown in their first two tours, but then stumbled against Swansea. Swansea were not in a period of particular growth and the only two players showing any flair were Wales Schoolboy players Willie Davies and Haydn Tanner. During the game Merv Corner could not contain the attacking bursts from Tanner, the New Zealand flankers were drawn in which in turned allowed Davies the freedom to run which Claude Davey finished off with two tries. Jack Manchester's response to the Swansea win was to ask the New Zealand press "Tell them we have been beaten, but don't tell them it was by a pair of schoolboys". This win gave Swansea the honour of being the first club team to have beaten all three major Southern Hemisphere touring teams. The All Blacks were unbeaten in the next twenty matches, but lost to Wales in a classic game which Wales managed to win in the last ten minutes of the game after the Welsh hooker, Don Tarr, was stretchered off with a broken neck.

Post-war Welsh rugby 1945-1959

The post-war years saw strong club teams emerge, but it wasn't until the 1950s that a true blend of players could be produced to translate club success into international victories. The coming of television saw an upsurge in popularity for the national team, but a decline in club support. Success was gained in the Five Nations Championship, Wales supplied many players to the ranks of the British Lions and New Zealand was beaten for the last time that century.

The decades following on from the Second World War were a boom time for Welsh rugby, though it took until the 1950s for the benefits to be seen on the playing fields. Although Britain was suffering from a post-war slump, attendance figures at club grounds saw an increase as rugby was again embraced as a spectator sport.[34] Towns and villages which had seen their club disbanded during wartime saw their teams re-established. The WRU had 104 member clubs during the 1946-47 season; by the mid fifties there were 130, even though the Union had done nothing to relax its strict membership regulations.[34]

By the 1950s Britain and Wales were beginning to benefit from improved economic conditions. This saw growth in consumer power and spending, which drew many people away from traditional spectator past times, such as sport and the cinema. With a newfound wealth the populace began switching from social pursuits to home entertainment, with the biggest draw being the availability of television. From the mid-fifties there was a significant drop in gate receipts as television became more and more popular. During the 1955 Five Nations Championship, the Scotland v. Wales match was televised live; at the same time an Aberavon v. Abertillery game which would normally draw a crowd of 4000 was unable to muster 400. This created a situation whereby rugby in Wales was gaining in popularity due to the number of people who could now watch the international matches, but support at club level declined.[34] This forced club committees to adopt different strategies to keep their clubs afloat. Many teams set up 'coupon funds' to allow clothing rations to be contributed by members to buy kit. With careful management and thrift most clubs not only survived but grew. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, with little money, many clubs were able to build new facilities or even own their grounds and club-houses for the first time in their history.[35] In 1951 Glamorgan Wanderers purchased the Memorial Grounds in Ely and in 1952 Llanelli were able to purchase the rugby portion of Stradey Park. Similarly, 1954 saw Blaina construct a new stand while Llanharan were able to build their first changing rooms procured from RAF surplus units. These events were typical of club expansion through the 50s. It was around this time that club social activities were extended including the introduction of ladies’ committees.[35]

Clubs also took matters into their own hands to promote themselves and their sport. 1947 saw the first unofficial club championship, won by Neath in its inaugural year, but dominated by Cardiff and Ebbw Vale until the 1960/61 season. In 1954 Welsh rugby sevens had their own tournament with the introduction of the Snelling Sevens competition, while Glamorgan County RFC introduced the Silver Ball Trophy in 1956 for the promotion of second tier clubs in the region.

The national team, after unconvincing displays during the 1940s, found unexpected success in the early 1950s winning the Grand Slam twice; in 1950 and 1952. The 1950 win came after a disastrous 1949 campaign, which saw Wales collect the wooden spoon; but after an opening win over England, the team finished the last three matches conceding only three points. The tournament saw the emergence of Welsh record breaking player Ken Jones as a world class wing; who is most remembered for his late try against the 1953 touring New Zealand team. The 1950 championship is also remembered for the tragic events following the away win over Ireland, when a chartered flight, returning from the Triple Crown winning match, crashed at Llandow. Seventy five Welsh fans and five crew died in the accident; at the time it was the world's worst civil air disaster.[36]

The second golden era 1969-1979

The zenith of Welsh rugby was the 1970s, when Wales had players such as Barry John, Gareth Edwards, Phil Bennett and JPR Williams. Wales won four consecutive Triple Crowns. The strong Pontypool front row of Graham Price, Bobby Windsor & Charlie Faulkner were all manual workers, and Robin McBryde was formerly the holder of the title of Wales's strongest man.

Gareth Edwards was voted the greatest player of all time in a players poll in 2003 and scored what is widely regarded as the greatest try of all time in 1973 for the Barbarians against New Zealand.

The start of the professional era: 1980 to 2012

The 1980s and early '90s were a difficult time for Welsh rugby union when the team suffered many defeats. Harsh economic times in the eighties meant that players such as Jonathan Davies and Scott Gibbs were tempted to 'go North' to play professional rugby league in order to earn a living.

In 2003/4 the Welsh Rugby Union voted to create five regions to play in the Celtic League (now the Pro14) and represent Wales in European competition. This soon became four when the Celtic Warriors were liquidated after just one season.[37] The WRU have announced their hopes of developing a fifth region in North Wales in the long run; the team at the centre of this plan is now known as RGC 1404.[38]

In recent years, Welsh Premier Division and Welsh Championship club rugby has faced increased financial hardship, with historic clubs at threat. Premiership side Neath RFC had received a now-resolved winding up petition from HM Revenue and Customs,[39] while Championship team Pontypool RFC have had to fund-raise from supporters to remain at their ground.[40]

Regional Rugby and future reforms: 2013 to present

Created by David Moffat in 2003,[41] Welsh rugby follows a region system with a top tier composed of four club regions.[42] This arrangement has however faced a number of funding issues in recent years. The regions currently operate on a 2009 Participation Agreement which expires in 2019.[43]

The regions in 2013 protested against a new agreement, as they felt it did not offer any funding commitments or clarity regarding competitions such as the Heineken Cup[43]. The Union retorted that funding would increase, but that regions would need to commit to the framework or risk losing their revenue streams.[43]

Project Reset

In 2018 the WRU launched Project Reset[44] to review regional arrangements. Due to the growing strength of French Top 14 and English Premiership Rugby sides, the WRU have increase salaries to bring Welsh international players such as Taulupe Faletau, Dan Biggar, Ross Moriarty, and Rhys Webb back into the Welsh league system. Yet the Union now feel the salary arrangements are unsustainable.

The WRU has established the Professional Rugby Board[45] to handle the proposed changes, composed of representatives from both the WRU and the regions.

Proposal 1 - Merge Scarlets/Ospreys and Blues/Dragons

Under one proposal, the region system would decrease from four sides to two. Ospreys and the Scarlets would merge, as would Cardiff Blues and Dragons.[46] Such proposals face widespread opposition from sections of supporters whose local loyalties would prevent them from travelling to traditionally 'rival' grounds to follow their team, standing in the terraces with their bitter rivals. Yet opponents of the proposal have pointed to the struggles of the Scottish rugby union team in test fixtures since switching to a two-region model dominated by Edinburgh and Glasgow Warriors.

Proposal 2 - Ending the Dragons franchise, or move it to North Wales

As the poorest performing Welsh region, the WRU have reportedly discussed moving the Dragons to North Wales,[47] or closing it altogether. This would be challenging given the side's contractual commitments, and its guarantees to ground share at Rodney Parade with Newport RFC and EFL League Two side Newport County A.F.C. until 2021.[48] The WRU have proposed the resulting space then be filled by a North Wales side taking the place of Conwy-based, semi professional RGC 1404.

In recent years Dragons have improved their attendances however, so such a move is considered highly controversial and financially ineffective.[47] The WRU nonetheless own both the team and the ground, so have strong control over the franchise's future.

A regional rugby franchise, originally known as Rygbi Gogledd Cymru (Welsh language for "Rugby North Wales") and later known as RGC 1404, was established in North Wales; plans called for the side to enter the Welsh Premier Division as early as 2010–11 and eventually the Celtic League/Pro12, but the venture was unsuccessful and was liquidated in 2011. The team, however, continues to play as part of Wales' national rugby academy. RGC 1404 also had a partnership with Rugby Canada by which the franchise would have a secondary role of developing players for the Canada national rugby union team, at least until enough local players were developed to fill a complete competitive squad.

Proposal 3 - Merging Cardiff Blues and Ospreys

As the most successful side in Pro14 (previously Celtic League) history, Ospreys now face significant issues, with reports of debts and stalled contract negotiations[49] threatening their claim to players such as Alun Wyn Jones[50] and head coach Allen Clarke.[51] Managing director Andrew Millward had described the struggle, involving year long budget cuts and structural flaws in the Welsh rugby system,[52] as leaving Wales unable to compete with rivals IRFU and FRR.

Facing a merger with Cardiff Blues however, Ospreys supporters have pushed back, arguing that the removal of the Ospreys franchise from the Swansea region would leave one of Wales' rugby heartlands without a local region side,[53] instead forced to travel to their rivals ground at Cardiff Arms Park.

Blues supporters also point to the fierce battle their side won to remain in their traditional Cardiff RFC colours and name back in 2003, and are unwilling to adopt a new identity.[46]

Proposal 4 - Merge Ospreys and Scarlets

More recent discussions have punted merging western sides Scarlets and Ospreys, with the Llanelli and Swansea teams either sharing grounds or moving fully. Scarlets however opposed such a merger with Ospreys back in 2003, with the late Stuart Gallacher famously opposed to any arrangement which would have ended the Scarlets name.

Governing body

The Welsh Rugby Union is the governing body for rugby union in Wales. Their responsibilities include producing the national team and the four regional franchises Cardiff Blues, Scarlets, Dragons, and Ospreys.

Competitions

Wales' four professional rugby regions play in the Pro14 league and take part in the European Rugby Champions Cup, European Rugby Challenge Cup and Anglo-Welsh Cup. The first two of these competitions, set to launch in 2014–15, replace the now-defunct Heineken Cup and Amlin Challenge Cup. Since 2006 they have also competed in the Anglo-Welsh Cup against clubs from the English Premiership.

There is also a Welsh Premier Division and WRU Challenge Cup competed for by Wales' traditional club teams. Starting in 2009–10, the four Home Unions have instituted the British and Irish Cup, an annual competition for semi-professional teams throughout Britain and Ireland; beginning with the 2013–14 edition, the WRU conducts a play-off among the 12 Premier Division clubs to determine the four that will be entered in the British and Irish Cup.

Popularity

Rugby union has a particular hold on the national psyche of Wales, especially the Six Nations tournament.

The first proof of Wales as a nation embracing the sport of rugby union is reflected in the rapid growth of rugby clubs in the late 19th century. Within a period of 25 years, from 1875 to 1900, most towns and villages in South Wales were represented by at least one team, though it would take until the 1930s for the North of Wales to set up their own leagues.

Although difficult to prove popularity, two events that took place early in the history of Welsh rugby illustrate its growing influence on the people of Wales. The first was the Gould Affair, when a testimonial fund was set up for Welsh international Arthur Gould, instigated by a local newspaper. From an initial fund of one shilling the public response saw the amount reach into hundreds of pounds, mainly from working-class families with little spare money. The second incident was during the Tonypandy Riot of 1910, when the striking coalminers attacked the shops and premises in the town centre. 80 police officers and 500 civilians were injured and one person died. Over 60 establishments were attacked and looted, with only two buildings avoiding damage. One was a jewelers which had roller shutters, the other was the chemist shop owned by Willie Llewellyn, which despite the chaos of the events was spared due to his services to Wales on the playing field.[54][55][56]

For the match against Scotland in 2005, 40,000 Welsh people went to Edinburgh to watch the game. Over 10,000 gathered on "Henson Hill" to watch a big screen of Wales v. Ireland that gave Wales its first Grand Slam since 1978. The result was greeted well amongst fans and was even used to explain a sudden economic surge.

Since 2013, the Millennium Stadium hosts the Judgement Day, a double-header fixture of the four Pro12 teams. The first two editions had over 30,000 spectators. The 2015 edition had 52,762 spectators, the highest in the history of the league.

The choral tradition of Wales manifests itself at rugby games in singing. Popular songs among the fans are 'Delilah' by Tom Jones, 'Cwm Rhondda' and 'Calon Lan' and in part replace the normal chanting of other Rugby supporters.

Statistics

According to WR, Wales has 239 rugby union clubs; 2321 referees; 28,702 pre-teen male players; 21,371 teen male players; 19,000 senior male players (total male players 69,073) as well as 1,000 teen female players; 1,056 senior female players (total female players 2,056).[57]

Demographics

Whereas rugby in England fractured into the two separate sports of rugby union and rugby league over the issue of money, Wales for the most part stayed loyal to the union game. There were some attempts to run professional rugby league sides in Wales but the heartland of Welsh rugby was simply too far from Yorkshire and Lancashire for this to be sustained.

There has always been an element of class warfare to rugby union in Wales. In 1977 Phil Bennett's pre-game pep talk before facing England produced a memorable quote:

Look what these bastards have done to Wales. They've taken our coal, our water, our steel. They buy our homes and live in them for a fortnight every year. What have they given us? Absolutely nothing. We've been exploited, raped, controlled and punished by the English — and that's who you are playing this afternoon.[58]

The Welsh valleys north of Cardiff produced so many quality number tens that it was often referred to as 'The Outside Half Factory' immortalised in a song by Max Boyce. Boyce's humour refers to rugby union very often and he has written many songs about the trials and tribulations of following the game as a fan e.g. 'Asso Asso Yogoshi', 'The Scottish Trip', 'Hymns and Arias'.

The national team

Wales compete annually in the Six Nations, which they have won 27 times, the last being in 2019. Wales have also appeared in every World Cup that has been held, and achieved their best result in the 1987 tournament, when they finished third. The national team play at the Millennium Stadium, built in 1999 to replace the old National Stadium. Wales play in scarlet jerseys, white shorts and green socks, with the jersey sporting the Prince of Wales's feathers as their official badge, underlining the close bond between the WRU and the English royal family. Every four years the British and Irish Lions go on tour with players from Wales as well as England, Ireland and Scotland. In 2013, during the third and final Test match of the British and Irish Lions tour of Australia, Wales fielded 10 players in the 15 man starting lineup. The Lions went on to win the game with ease, securing the series 2-1.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rugby union in Wales. |

Bibliography

- Goodwin, Terry (1984). The International Rugby Championship 1883-1983. Glasgow: Willow Books. ISBN 0-00-218060-X.

- Morgan, Prys (1988). Glamorgan County History, Volume VI, Glamorgan Society 1780 to 1980. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Richards, Huw A Game for Hooligans: The History of Rugby Union (Mainstream Publishing, Edinburgh, 2007, ISBN 978-1-84596-255-5)

- Smith, David; Williams, Gareth (1980). Fields of Praise: The Official History of The Welsh Rugby Union. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-0766-3.

- Thomas, Wayne (1979). A Century of Welsh Rugby Players. Ansells Ltd.

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-03. Retrieved 2011-09-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Fields of Praise, The Official History of the Welsh Rugby Union 1881-1981, David Smith, Gareth Williams (1980) pp41 ISBN 0-7083-0766-3

- Smith (1980), pg18.

- Smith (1980), pg22.

- Thomas, Wayne 'A Century of Welsh Rugby Players, 1880-1980'; Ansells Ltd. (1979)

- Smith (1980), pg11.

- Smith (1980), pg11-12.

- Smith (1980), pg14.

- Smith (1980), pg41.

- Smith (1980), pg40.

- Smith (1980), pg481.

- Thomas (1979), pg40.

- David Parry-Jones (1999). Prince Gwyn, Gwyn Nicholls and the First Golden Era of Welsh Rugby (1999) pp. 36. seren.

- Smith (1980), pg120.

- Smith (1980), pg121.

- Morgan (1988), pg391.

- Smith (1980), pg195.

- Thomas (1979), pg43.

- Gallagher, Brendan (2008-01-29). "A century since Wales first won Grand Slam". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

- Smith (1980), pg224.

- Smith (1980), pg225.

- Smith (1980), pg259.

- Morgan (1988), pg394.

- Smith (1980), pg260.

- Smith (1980), pg232.

- Smith (1980), pg234.

- Smith (1980), pg236.

- Smith (1980), pg240.

- Smith (1980), pg241.

- Smith (1980), pg243-44.

- Smith (1980), pg261.

- Smith (1980), pg268.

- Smith (1984), pg182.

- Smith (1980), pg330.

- Smith (1980), pg331.

- John Davies, Nigel Jenkins, Menna Baines and Peredur Lynch The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales (2008) pp816 ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6

- "WRU axe falls on Warriors". bbc.co.uk. 2004-07-01. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- "WRU plan for northern development team". The Independent. London. 2008-09-09. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- "WRU must 'protect' clubs from the financial plight faced by Neath, says Paul Thorburn". 2018-12-07. Retrieved 2019-02-26.

- Dewey, Philip (2018-07-19). "The rise and fall of Pontypool, the town built on rugby". walesonline. Retrieved 2019-02-26.

- WalesOnline (2003-01-28). "Overseas and out". walesonline. Retrieved 2019-02-26.

- Orders, Mark (2018-04-05). "Chronicling 15 years of Welsh regional rugby - has it worked?". walesonline. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- Thomas, Simon (2013-12-30). "Welsh rugby in crisis: Everything you need to know about the WRU v regions war and what happens next". walesonline. Retrieved 2019-02-26.

- Orders, Mark (2019-01-07). "The monumental two-day Welsh rugby meeting about to take place". walesonline. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- Thomas, Simon (2018-07-11). "Project Reset uncovered: confidential new Welsh rugby deal changes everything". walesonline. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- Orders, Mark (2019-01-14). "Radical plan for Ospreys-Scarlets and Dragons-Blues mergers tabled". walesonline. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- Thomas, Simon (2019-02-26). "Welsh rugby's tense stand-off explained as a region fights for its life". walesonline. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- "As lease ticks down uncertainty is growing over Newport County's future at Rodney Parade". South Wales Argus. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- Southcombe, Matthew (2019-02-22). "Sean Holley claims Ospreys are on the verge of extinction". walesonline. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- "Alun Wyn Jones: Ospreys hopeful of keeping Wales captain". 2019-02-26. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- "Ospreys: Clarke 'delighted' at assurances over their future". 2019-02-22. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- "Ospreys: 'Worst week of our life' says managing director Millward". 2019-02-24. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- "Welsh rugby: Talks over radical overhaul with possible new region". 2019-02-26. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. John Davies, Nigel Jenkins, Menna Baines and Peredur Lynch (2008) pg512 ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6

- Rhondda Cynon Taff Library Service - Tonypandy Archived 2008-08-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Morgan (1988), pg393

- "Welsh R.U." irb.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2006.

- Philip, Robert (2006-03-09). "Actions speaks louder than words for White". London: telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rugby union in Wales. |

- The BBC's Welsh rugby union news page

- IC Wales's rugby union news page

- Gwlad Popular fan site for supporters of rugby union in Wales