Rumaliza

Muhammad bin Khalfan bin Khamis al-Barwani (Arabic: محمد بن خلفان بن خميس البرواني) (born c. 1855), commonly known as Rumaliza, was an Arab trader of ivory active in Central and East Africa in the last part of the nineteenth century. He was a member of the Arabian Barwani tribe. With the help of Tippu Tip he became Sultan of Ujiji. At one time he dominated the trade of Tanganyika, before being defeated by Belgian forces under Baron Francis Dhanis in January 1894.

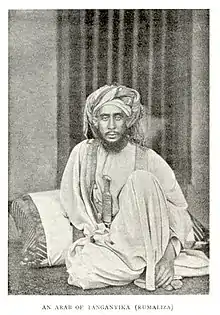

Rumaliza | |

|---|---|

Rumaliza, pictured in January 1900. | |

| Born | Muhammad bin Khalfan bin Khamis al-Barwani c. 1855 |

| Died | After 1894 |

| Occupation | Sultan of Ujiji |

| Known for | Ivory trading |

Background

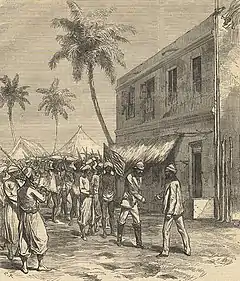

The trade in slaves from East Africa dates back thousands of years. Inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula are documented as trading in slaves from the East African coast as early the second century AD.[1] The Arabs established a series of trading posts along the coast which geographers referred to as the zanj. Through prolonged contact with the Arabs, a distinctive Swahili ("coastal") culture developed among the Bantu peoples of the region and some converted to Islam.[2] Although the Swahili language has Bantu roots, it includes many words of Arabic origin.[3] For many years, Zanzibar was considered part of the Omani Empire.[4] The Swahili and Arab traders obtained slaves in the interior of East Africa and sold them in the great markets like Zanzibar on the coast. The Arab slave trade peaked in the nineteenth century in response to growing local and international demand.[3]

Biography

Early life and trading activities

Rumaliza was born at Lindi, on the Indian Ocean coast in the south of modern Tanzania, in around 1855. He was educated at Zanzibar during the reign of Majid bin Sa'id (r. 1856–70).[5] He became a leader in the Islamic Qadiriyya brotherhood.[6] The Arab trader Tippu Tip from Zanzibar increasingly pushed inland towards the modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo and reached the Luba region in the late 1850s trading in slaves, ivory, and copper. Relying on force as needed to defeat uncooperative local chiefs, he steadily expanded his trading empire. In 1875, he established his capital as Kasongo.[7] Rumaliza spent some time with Tippu Tip at Tabora in western Tanzania, and is said to have acquired his name from the nearby village or suburb called Rumaliza or Lumaliza.[8] Rumaliza formed a trading alliance with Tippu Tip.

A market where salt could be exchanged for other goods was established at Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika in 1840. Tippu Tip and Ruwaliza established themselves there in 1881.[9] From 1883 Rumaliza was the leader of the Swahili community at Ujiji.[6] Rumaliza and his Magwangwara auxiliaries occupied five posts on the northeast coast of Lake Tanganyika between 1884 and 1894. He launched a series of raids into the mountains and up the Rusizi River valley as far as Lake Kivu.[10]

The HM Company, a trading organization led by Tippu Tip, appeared in 1883. It was backed by Sultan Barghash bin Said of Zanzibar and Taria Topan. The International African Association (IAA) offered their support if Tippu Tip would help them achieve control of the territories in which he had established strong points although it was notionally committed to eliminating the Arab slave trade.[11] Tippu used trade goods advanced to the company to form an alliance with Rumaliza, who had many men but was short of money and could not obtain loans. The new company operated between Ujiji and Stanley Falls and in areas to the south of this line, controlled by Abdullah ibn Suleiman as lieutenant of Tippu Tip and Rumaliza.[6] Between 1885 and 1892, after the death of Mwenge Heri, Rumaliza consolidated his power over the Masanze, Ubvari, Umona and Ubembi people. He wanted to open new trade routes towards Maniema to the west and Ituri to the north.[12]

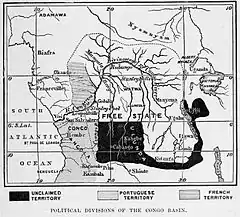

In 1886 Tippu Tip recognized the Congo Free State, which superseded the IAA, and was made Governor of the eastern areas that were covered by his trading network. In 1890 Rumaliza provided large amounts of ivory to the African Lakes Company for transport.[6] Taria Topan died in late 1891. Tippu Tip obtained part of the estate as payment for outstanding debts. Rumaliza sued for a share in the Dar es Salaam court as a newly-loyal subject of German East Africa which had consolidated control in modern-day Tanzania. He was awarded some of Tippu's property held in the German colony.[13]

Stories told in the Uele, Aruwimi, Tshuapa, Maniema and Kisangani areas, regions distant and far away from one another, associated Rumaliza and his parties with the kidnapping of women, cutting off men's genitals (to be captured and sold as eunuch slaves), cutting off legs, arms and hands, piercing of noses and ears, burning villages and killings.[14]

Conflict with Christian missionaries

The Catholic White Fathers missionaries had established posts in the northwest of Tanganyika that formed an obstacle to Arab incursions into the Maniema region, protected by Captain Léopold Louis Joubert, a former Papal Zouave.[15] Rumaliza tolerated the foundation of the missions at Mulwewa in 1880 and Kibanga in 1883, but would not allow establishment of a station at Ujiji. In 1886,he tried to conquer Burundi but was defeated by the king Mwezi Gisabo in Uzige situated in the actual city Bujumbura. In May 1890 a group of Arabs came close to attacking the White Fathers]] mission at Mpala on the west shore of Lake Tanganyika, and only withdrew after a storm destroyed a number of their supply boats. Before leaving they confirmed that Rumaliza had given orders to them not to harm the missionaries.[16] In September 1890 the White Fathers Léonce Bridoux and Francois Coulbois visited Ujiji, where they found Rumaliza and Tippu Tip. The two slavers were friendly, and Rumaliza was anxious that the missionaries gave a good report of him to Emin Pasha, who was expected at Ujiji. Rumaliza apologized for the hostility his men had shown to the missionaries, saying he was unable to control them.[16]

However, Rumaliza was determined to eliminate Léopold Louis Joubert, commander of the forces defending the White Fathers, who was disrupting the slave trade.[17] By 1891 the slavers had control of the entire western shore of the lake apart from Mpala and the Mrumbi plain.[18] Joubert's position was ambiguous. The Belgians had appointed Tippu Tip as their lieutenant in the region, but Joubert refused to recognize the authority of the slaver.[19] During a lull in January 1891, Father I. Moinet visited Ujiji where he found Rumaliza flying a German flag and saying he was waiting for the Germans to arrive so he could hand over to them. In a letter to Joubert in April 1891, Rumaliza asked if he was employed by the missionaries or by the government of the Congo. Joubert was evasive in his reply, pointing out that Rumaliza sometimes flew the German flag, sometimes the flag of Zanzibar and sometimes that of Britain.[20]

War and defeat

The Congo Free State became stronger and less tolerant of Arab strongmen, determined to stamp them out.[13] By 1892 Rumaliza dominated Tanganyika from his base at Ujiji on the old slave route that led from Stanley Falls up the Lualaba River to Nyangwe, east to Lake Tanganyika and then via Tabora to Bagamoyo opposite Zanzibar. The total number of Swahili fighters in this huge region numbered around one hundred thousand, but each chief acted independently. Although experienced in warfare, they were poorly armed with simple rifles. The Belgians had just six hundred troops divided between the camps at Basoko and Lusambo, but were much better armed and had six cannons and a machine gun.[21] A Belgian expedition under Captain Jacques came to the relief of Joubert in 1892, and then established a position at Albertville where Rumaliza's troops were defeated by a relief column while besieging the post.[15]

The Belgian forces under Francis Dhanis launched a campaign against the slave dealers in 1892, and Rumaliza was one of the main targets.[22] Dhanis advanced up the river. He reached Nyangwe on 4 March 1893 and Kasongo on 22 April 1893, finding both towns abandoned. He found a huge supply store at Kasongo including ivory, ammunition, food and luxuries such as gold and crystal tableware. For the next six months Dhanis remained inactive, while Rumaliza's forces were swelled by Swahili fighters who had escaped after defeat by Dhanis.[23]

In 1893 Tippu Tip advised Rumaliza to retire from the trade, but Rumaliza first had to look after his people at Lake Tanganyika.[13] Rumaliza raised a strong force, which clashed with Dhanis' column on 15 October 1893 causing the death of two European leaders and fifty of their soldiers. On 19 October 1893 Rumaliza attacked a position one day's march from Kasongo.[24] Dhanis concentrated his forces and defeated Rumaliza. A column under Captain Hubert Lothaire pursued him to the north of Lake Tanganyika, destroying his fortified positions along the route. At the lake they joined with the anti-slavery expedition led by Captain Alphonse Jacques.[15]

By 24 December 1893 Dhanis had obtained reinforcements and was ready to advance again. Rumaliza had also received assistance. Dhanis sent one column under Gillain to prevent Rumaliza from retreating, and another under De Wouters to advance on Rumaliza's fort near Bena Kalunga. A group of fresh forces coming to Rumaliza's aid from Tanganyika was headed off, and Dhanis's forces closed in on Rumaliza's two fortified bomas.[25] On 9 January 1894 Belgian reinforcements arrived under Lothaire, and the same day a shell blew up Rumaliza's ammunition store and burned down the fort containing it. Most of the occupants were killed while attempting to escape. Within three days the other forts, cut off from water supplies, surrendered. More than two thousand prisoners were taken, although Rumaliza himself managed to escape.[26] Rumaliza took refuge in the German territory of Tanganyika.[23]

References

Notes

Citations

- Wink 2002, p. 30.

- Wink 2002, p. 28.

- Insoll 1997, p. 523.

- Wink 2002, p. 29.

- Martin 2003, p. 169.

- Oliver 1985, p. 563.

- Simba 1997, p. 138.

- Martin 2003, p. 170.

- Chrétien 1993, p. 172.

- Chrétien 1993, p. 134.

- Oliver 1985, p. 562.

- Rumaliza 1975, p. 620.

- Oliver 1985, p. 569.

- Osumaka Likaka (2009). Naming Colonialism: History and Collective Memory in the Congo, 1870–1960. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 104.

- Ergo 2005, p. 43.

- Swann & Bennett 2012, p. 31.

- Coosemans 1951, p. 518.

- Shorter 2003.

- Swann & Bennett 2012, p. 32.

- Swann & Bennett 2012, p. 33.

- Ndaywel è Nziem, Obenga & Salmon 1998, p. 296.

- Ergo 2005, p. 41.

- Ndaywel è Nziem, Obenga & Salmon 1998, p. 297.

- Ergo 2005, p. 42.

- Boulger 1898, p. 179.

- Boulger 1898, p. 180.

Sources

- Boulger, Demetrius Charles (1898). The Congo State: Or, the Growth of Civilisation in Central Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-108-05069-2. Retrieved 2013-04-13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chrétien, Jean-Pierre (1993). Burundi, l'histoire retrouvée: 25 ans de métier d'historien en Afrique. KARTHALA Editions. p. 134. ISBN 978-2-86537-449-6. Retrieved 2013-04-13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coosemans, M. (1951). "JOUBERT (Leopold Louis)". Biographie Coloniale Belge (in French). II. Inst. roy. colon. belge. Retrieved 2013-04-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ergo, André-Bernard (2005). Des bâtisseurs aux contempteurs du Congo Belge: L'odyssée coloniale. Editions L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-7475-8502-6. Retrieved 2013-04-12.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Insoll, Timothy (1997). "Swahili". The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery: A-K ; Vol. II, L-Z. ABC-CLIO. p. 623. ISBN 978-0-87436-885-7. Retrieved 2013-04-13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martin, B. G. (2003-02-13). Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53451-2. Retrieved 2013-04-13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ndaywel è Nziem, Isidore; Obenga, Théophile; Salmon, Pierre (1998). Histoire générale du Congo: De l'héritage ancien à la République Démocratique. De Boeck Supérieur. p. 296. ISBN 978-2-8011-1174-1. Retrieved 2013-04-13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oliver, Roland Anthony (1985). The Cambridge History of Africa. Volume 6: From 1870 to 1905. Cambridge University Press. p. 562. ISBN 978-0-521-22803-9. Retrieved 2013-04-12.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Rumaliza". Hommes et destins: dictionnaire biographique d'outre-mer. Académie des sciences d'outre-mer. 1975. ISBN 978-2-900098-03-5. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- Shorter, Aylward (2003). "Joubert, Leopold Louis". Dictionary of African Christian Biography. Archived from the original on 2013-05-24. Retrieved 2013-04-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simba, Malik (1997). "Central Africa". The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery: A-K ; Vol. II, L-Z. ABC-CLIO. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-87436-885-7. Retrieved 2013-04-13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Swann, Alfred J.; Bennett, Norman (2012). Fighting the Slave Hunters in Central Africa: A Record of Twenty-Six Years of Travel and Adventure Round the Great Lakes. Routledge. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-136-25681-3. Retrieved 2013-04-12.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wink, Andre (2002). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7Th-11th Centuries. BRILL. ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8. Retrieved 2013-04-13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)