Sápmi

Sápmi (Northern Sami: [ˈsapmi],[1] Lule Sami: Sábme / Sámeednam, Southern Sami: Saepmie, Ume Sami: Sábmie, Inari Sami: Säämi, Skolt Sami: Sääʹmjânnam) is the cultural region traditionally inhabited by the Sámi people. Sápmi is in Northern Europe and includes the northern parts of Fennoscandia.

Sápmi | |

|---|---|

Flag | |

Anthem: Sámi soga lávlla | |

Location of Sápmi in Europe | |

| Recognised national languages | Sámi languages |

| Regional | Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, Meänkieli, Kven and Russian |

| Integrated parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia respectively, but with varying degrees of autonomy for the Sami population | |

| Area | |

• Total | 400,000 km2 (150,000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 2,000,000 total

|

• Density | 5/km2 (12.9/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 to +3 (CET, EET, FET) |

The region stretches over four countries: Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. On the north it is bounded by the Barents Sea, on the west by the Norwegian Sea, and on the east by the White Sea.[2][3] The area is historically referred to as Lapland (/ˈlæplænd/) in English, although the term "Lapp" for its inhabitants is now often discouraged.[4]

Sápmi refers to the areas where the Sámi people have traditionally lived, but overlaps with other regions and definitions. In practice most of the Sámi population is largely concentrated in a few traditional areas in the northernmost part of Sápmi, such as Kautokeino and Karasjok, with the exception of those who have left for the larger cities.

The Sami people are estimated to make up around only 2.5% to 5% of the total population in the Sápmi area.[lower-alpha 1] No political organization advocates secession, although several groups desire more territorial autonomy and/or more self-determination for the region's indigenous population.

Etymology

Sápmi (and corresponding terms in other Sami languages) refers to both the Sami land and the Sami people. The word "Sámi" is the accusative-genitive form of the noun "Sápmi"—making the name's (Sámi olbmot) meaning "people of Sápmi". The origin of the word is speculated to be related to the Baltic word *žēmē, meaning "land".[5] Also "Häme", the Finnish name for Tavastia, a historical province of Finland, is thought to have the same origin, and the same word is at least speculated to be the origin of "Suomi", the Finnish name for Finland.

Sápmi is the name in North Sami, while the Julev Sami name is Sábme and the South Sami name is Saepmie. In Norwegian and Swedish the term Sameland is often used.

In modern Swedish and Norwegian, Sápmi is known as "Sameland", but in older Swedish it was known as "Lappmarken", "Lappland", and Finnmark, respectively.[6] Originally these two names did refer to the entire Sápmi, but subsequently became applied to areas exclusively inhabited by the Sami. "Lappland" (Laponia) became the name of Sweden's northernmost province (landskap) which in 1809 was split into one part that remained Swedish and one part falling under Finland (which became part of the Russian Empire). "Lappland" survives as the name of both Sweden's northernmost province and Finland's, also containing part of the old Ostrobothnian province. The terms "Lapp" and "Lappland" are regarded as offensive by some Sami people, who prefer the area's name in their own language, "Sápmi".[7]

In older Norwegian, Sápmi was known as "Finnmork" or "Finnmark"; which is now the name of Norway's northernmost county. Northern Norway and Murmansk Oblast are sometimes marketed as Norwegian Lapland and Russian Lapland, respectively.

In the 17th century, Johannes Schefferus assumed the etymology of the term "Lapland" to be related to the Swedish word for "running", "löpa" (cognate with English, to leap).[8]

Geography

Landscape

The largest part of Sápmi lies north of the Arctic Circle. The western portion is an area of fjords, deep valleys, glaciers and mountains, the highest point being Mount Kebnekaise (2,111 m [6,926 ft]), in Swedish Lapland. The Swedish part of Sápmi is characterized by great rivers running from the northwest to the southeast. From the Norwegian province of Troms and Finnmark and eastward, the terrain is that of a low plateau with many marshes and lakes, the largest of which is Lake Inari in Finnish Lapland. The extreme northeastern section lies within the tundra region, but it does not have permafrost.

In the 19th century scientific expeditions to Sápmi were undertaken, for instance by Jöns Svanberg.[9]

Climate

The climate is subarctic and vegetation is sparse, except in the densely forested southern portion. The mountainous west coast has significantly milder winters and more precipitation than the large areas east of the mountain chain. North of the Arctic Circle polar night characterize the winter season and midnight sun the summer season—both phenomena are longer the further north you go. Traditionally, the Sami divide the year in eight seasons instead of four.

Natural resources

Reindeer, wolf, bear, and birds are the main forms of animal life, in addition to a myriad of insects in the short summer. Sea and river fisheries abound in the region. Steamers are operated on some of the lakes, and many ports are ice-free throughout the year. All ports along the Norwegian Sea in the west and the Barents Sea in the northeast to Murmansk are ice-free all year. The Gulf of Bothnia usually freezes over in winter. The ocean floor to the north and west of Sápmi has deposits of petroleum and natural gas. Sápmi contains valuable mineral deposits, particularly iron ore in Sweden, copper in Norway, and nickel and apatite in Russia.

Cultural subdivisions

East Sápmi

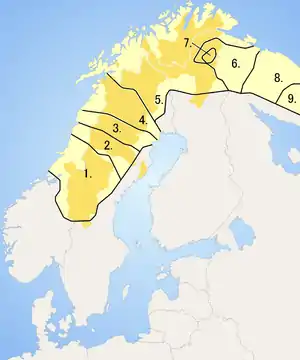

East Sápmi consists of the Kola peninsula and the Lake Inari region and is home to the eastern Sami languages. While being the most-heavily populated part of Sápmi, this is also the region where the indigenous population and their culture is weakest. Corresponds to the regions marked 6 through 9 on the map below.

Central Sápmi

Central Sápmi consists of the western part of Finland's Sami Domicile Area, the parts of Norway north of the Saltfjellet mountains and areas on the Swedish side corresponding to this. Central Sápmi is the region where Sami culture is strongest, and home to North Sami—the most widely used Sami language. In the southernmost part of this subregion, however, Sami culture is rather weak—this is where the moribound Bithun Sami language is used. The areas around the Tysfjord fjord in Norway and the river Lule in Sweden are home to the Julev Sami language, one of the more widely used Sami languages. These correspond to the regions marked 3 through 5 on the map below.

South Sápmi

South Sápmi consists of the areas south of Saltfjellet and corresponding areas in Sweden, and is home to the southern languages. In this area Sami culture is mostly visible inland and on the coast of Baltic Sea, and the languages are spoken by few. Corresponds to the regions marked 1 and 2 on the map below to the south-east of region 1 in Sweden.

Lapland

The inner parts of Sápmi are often referred to as Lappi. The name is also found on the Russian side as Laplandige (the name of a natural reservation) and the Norwegian landscape of Finnmark is sometimes titled the "Norwegian Lapland", especially by the travel industry.[10] Lappi- appears as a common component of place-names throughout central and southern Finland as well; in many cases, it probably refers to earlier Sami presence, though in some cases the underlying meaning may be merely "periphery" or "outlying district".

"Sides"

Finally, Sápmi may also be sub-divided into cultural regions according to the states' borders, that obviously affects daily life for people no matter their ethnicity. These regions are commonly referred to as "sides" by Sami, for example "the Norwegian side" (norgga bealli) or "the Finnish side" (suoma bealli).

Languages

(see text for explanation of numbers)

Sámi languages

The Saamic languages are the region's main minority languages and also its original languages. They belong to the Uralic language family, and are most closely related to the Finnic languages. Many Sami languages are mutually unintelligible, but the languages originally formed a dialect continuum stretching southwest–northeast, so that a message could hypothetically be passed between Sami speakers from one end to the other and be understood by all. Today, however, many of the languages are moribund and thus there are "gaps" in the original continuum.

On the map to the right numbers indicate Sámi Languages (Darkened areas represent municipalities that recognize Sami as an official language.): 1. South (Åarjil) Sámi, 2. Ume (Upme) Sámi, 3. Pite (Bitthun) Sámi, 4. Lule (Julev) Sámi, 5. North (Davvi) Sámi, 6. Skolt Sámi, 7. Inari (Ánár) Sámi, 8. Kildin Sámi, 9. Ter Sámi. Of these languages the North one is by far the most vital; whereas Ume, Pite and Ter seem to be dying languages. Kemi Sámi is extinct.

North Sami is subdivided into three main dialects: West, East, and Coast. The written standard is based on the Western dialect.

East Slavic languages

The language spoken by most people in the region is Russian, which is an East Slavic language. It is the dominant language on the Russian side of the border and also spoken by recently immigrated minority groups elsewhere in Sápmi. Earlier, a common pidgin language was spoken on the northern coast of Sápmi that combined elements of Russian, Norwegian, North Sami, and Kven. This language was known as Russenorsk. On the Russian side, there are also speakers of the East Slavic Belarusian and Ukrainian languages.

North Germanic (Scandinavian) languages

Norwegian and Swedish dominate the largest part of Sápmi, including the entire Southern region and most of the Central region. There also used to be minorities speaking Norwegian on the Kola Peninsula. The Scandinavian languages are to a very large degree mutually intelligible, much more so than South Sami and North Sami. The Norwegian dialects spoken particularly in North and Central Norway Sami areas differ very much from the written bokmål standard. In Central Sápmi the Sámi dialects have taken the Scandinavian language trait of having a more or less constant emphasis on the first syllable of each spoken word. In the inner and northernmost parts of Sweden and Norway, however, people often speak Norwegian and Swedish close to the written standard, though with a heavy Uralic accent.

Finnic languages

The Finnic (i.e. Baltic Finnic) languages are spoken on the Finnish (Finnish), Swedish (Meänkieli—spoken by the Tornedalians) and Norwegian (Kven) sides of the borders. There also used to be minorities speaking Finnish on the Kola Peninsula. The languages are as mutually intelligible as the Scandinavian languages. Other Finnic languages include Karelian, Estonian, Livonian, Veps, Votic and Izhoran. Many are mutually intelligible.

Demography

The number of people living in Sápmi is about 2 million, though it is difficult to give the precise number of inhabitants since certain counties and provinces only include parts of Sápmi. It is also difficult to account for the distribution of ethnic groups as many people have double or multiple ethnic identities—both seeing themselves as members of the majority population and being part of one or more minority groups.

Sami

Different criteria are set when calculating the number of Sami, but the number is generally between 80,000 and 100,000. Many live in areas outside Sápmi such as Oulu, Oslo, Stockholm and Helsinki. Some Sami people have migrated to places outside the Sapmi vernacular region, such as in Canada and the United States. Many Sapmi people have settled in the northern parts of Minnesota.[11]

Russians

About 900,000 people inhabit Murmansk province (oblast'), but parts of this area lie outside Sápmi. About 758,600 of Murmansk's population claim to be exclusively Russian. Ethnic Russians also live elsewhere in Sápmi. The Russian side of Sápmi is ethnically diverse, with particularly big Ukrainian and Belarusian minorities. The Sami are one of the minor minorities in this part of Sápmi.

Norwegians

About 850,000 people inhabit the Norwegian regions of North Norway (fully within Sápmi) and Trøndelag (mostly within Sápmi). However, many of the regions' inhabitants—particularly those of North Norway—are not exclusively Norwegian. Notable minority groups include the Sami, Finns, and Kvens.

Swedes

About 700,000 people inhabit the Swedish counties Norrbotten, Västerbotten, Västernorrland, and Jämtland. Many of the counties' inhabitants are not exclusively Swedish. Notable minority groups in the former three counties include the Sami, Tornedalians, and Finns.

Finns

13,226 people inhabit the Sami native region of Lapland, Finland. A great portion of these are Sami.

Tornedalians and Kvens

These two ethnic groups, closely related to each other and also the Finns, mainly live on the Finnish, Swedish and Norwegian sides of Nordkalotten, respectively. In Sweden, there are two meanings to the word 'Norrbotten'. One is the older 'landskap' Norrbotten, which is much smaller than the modern county, 'län', Norrbotten, which encompasses all of north Sweden from Jävre. Norrbottens län also encompasses the northern part of the 'landskap' Lappland. The modern county Norrbotten has only a small minority of reindeer-herding Sami. The Tornedalians, who have lived, hunted, fished and farmed, mainly south and east of the line of arable climate and land (that line mostly coincides approximately with the border between the two landscapes Lappland and Norrbotten) for 700–1000 years, is a much larger minority. There are also a lot of Tornedalians in the mining district around Kiruna and Gällivare, and the increasingly restrictions on leisure, movement, fishing, and hunting for all but the reindeer-herding Sami minority are controversial and contested in Norrbotten.

Politics

Sami political structures

Norway, Finland and Sweden all have Sami Parliaments that to varying degrees are involved in governing the region—though mostly they only have authority over the matters of the Sami citizens of the states in which they are situated.

Sami Parliaments

Every Norwegian citizen registered as a Sami has the right to vote in the elections for the Sami Parliament of Norway. Elections are held every four years by direct vote from seven constituencies covering all of Norway (six of which are in Sápmi), and run parallel to the general Norwegian parliamentary elections. This is the Sami Parliament with the most influence over any part of Sápmi, as it is involved in the autonomy established by the Finnmark Act. The parliament is in Kárášjohka and its current president is Aili Keskitalo from the Norwegian Sami Association.

The Sami Parliament of Sweden, situated in Kiruna (Northern Sami: Giron), is elected by a general vote where all registered Sami citizens of Sweden may attend. The current president is Lars-Anders Baer.

Voting for elections to the Sámi Parliament of Finland is restricted to inhabitants of the Sami Domicile Area. The Parliament is in Inari (Inari Sami: Aanaar), and its current president is Pekka Aikio.

In Russia there is no Sami Parliament. There are two Sami organizations that are members of the national umbrella organisation of indigenous peoples, the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON), and represent the Russian Sami in the Sami Council. RAIPON is represented in Russia's Public Chamber by Pavel Sulyandziga. On 14 December 2008 the first Congress of the Russian Sámi took place. The Conference decided to demand the formation of a Russian Sámi Parliament, to be elected by the local Sami. A suggestion to have the Russian Federation pick representatives to the Parliament was voted down with a clear majority. The Congress also chose a Council of Representatives that were to work for the establishment of a parliament and otherwise represent the Russian Sami. It is headed by Valentina Sovkina.[12]

Sami Parliamentary Council

On 2 March 2000, the Sami parliaments of Norway and Finland founded the Sami Parliamentary Council, and the Sami Parliament of Sweden joined two years later. Each parliament sends seven representatives, and observers are sent from the Sami organizations of Russia and the Sami Council. The Sami Parliamentary Council discuss cross-border cooperation, hand out the annual Gollegiella language development award, and represent the Sami people abroad.[13]

Saami Council

In addition to the parliaments and their common council, there is a Saami Council based on Saami organizations. This council also organizes interstate cooperation between the Saami, and also often represents the Saami in international fora such as the Barents Region. This organization is older than the Parliamentary Council, but not connected to the parliaments except that some of the NGOs double as party lists in Sami parliament elections.

Russian side

The Russian Federation consists of several types of subunits. The Russian side of Sápmi is within Murmansk Oblast. Oblasti are governed by popularly elected parliaments and formally headed by governors. The governors are nominated by the president of Russia, and accepted or rejected by the local parliaments. However, should the parliament refuse to accept the president's nominee, the president is entitled to dissolve parliament and call local elections. Currently, the acting governor is Andrey Chibis, who was appointed on 21 March 2019 after the resignation of Marina Kovtun.[14]

Murmansk Oblast covers the Kola Peninsula and is home to Murmansk, the largest city north of the Arctic Circle and in the Sápmi. It is subdivided into several districts, of which the geographically largest is Lovozersky District. This is also the part of Russia where the Sami population is most numerous and visible. In the west of the province there is a large natural reserve known as Laplandiya.

Norwegian side

The counties of Norway are governed by popularly elected assemblies, headed by county mayors. Formally, the counties are headed by county governors, but in practice these have limited influence today.

The largest of Norway's landscapes, Finnmárku (Northern Sami) or Finnmark (Norwegian), is in Sápmi and has a special form of autonomy: 95% (about 46,000 km2 [18,000 sq mi]) of the area is owned by the Finnmark Estate. The board of the Estate consists of equally many representatives from the Sami Parliament of Norway and Finnmark's county council. The two institutions appoint leaders of the board alternately. The administrative centre of Finnmárku (Finnmark) is Čáhcesuolu or Vadsø, in the far east of the county. The current county governor is Runar Sjåstad from the Norwegian Labour Party.

Romsa or Troms is southwest of Finnmárku. Its administrative centre is the city after which the county is named, Romsa or Tromsø. Romsa is North Norway's biggest city and Sápmi's biggest city after Murmansk. Current fylkesordfører is Terje Olsen from the Conservative Party. A similar solution to the Finnmark Estate, Hålogalandsallmenningen, has been proposed for Romsa county and its southern neighbour Nordlánda.

Nordland covers a long strip of coast that includes both North Sami, Julev Sami, Bithun Sami, and South Sami areas. Its administrative centre is Bådåddjo or Bodø. The current county governor is Mariette Korsrud from the Norwegian Labour Party.[15]

The southernmost parts of Norwegian Sapmi lie in Nord-Trøndelag and partially in Sør-Trøndelag, and the administrative centres of which are Steinkjer and Trondheim respectively. The latter city is outside Sápmi but well known for being the site of the first international Sami conference in February 1917. The county governors are Gunnar Viken (the Conservative Party) in Nord-Trøndelag and Tore Sandvik (Norwegian Labour Party) in Sør-Trøndelag.

Swedish side

Lapland is a large northwestern province of Sweden, wholly within Sápmi. The traditional provinces of Sweden are cultural and historical entities; for administrative and political purposes they were replaced by the counties of Sweden (län) in 1634.

Five counties are wholly or partially within Sápmi. Län are formally governed by the landshövding, who is an envoy of the government and runs the government-appointed länsstyrelse that coordinates administration with national political goals for the county. Much of county politics is run by the county council or landsting, which is elected by the inhabitants of the county; but the counties' top positions are still determined by those who win the general elections of Sweden.

Norrbotten is mostly covered by Sápmi, although the lower Tornedalen region is often excluded. The administrative centre is Luleå in the Julev Sami area (Norrbotten includes North, Julev and Bithun areas). Current landshövding is Per-Ola Eriksson of the Centre Party.

Sápmi covers the interior majority of Västerbotten, which are Ubmeje and South Sami regions. The administrative centre is Umeå, and the current landshövding is Chris Heister from the conservative Moderate Party.

Västernorrland is an old part of Sapmi and still is. There are a lot of Sami in the coast of Baltic Sea (Gulf of Bothnia).

Jämtland is sometimes considered a part of the Sápmi cultural region, and is a South Sami county. The administrative centre is Östersund. Current landshövding is Jöran Hägglund from the centre party Centerpartiet.

Finnish side

Finland is subdivided into nineteen regions (maakunta). The regions are governed by regional councils, which are generally forums of cooperation between the municipalities and not elected by direct popular vote. Lapland (Lappi) is the northernmost of the regions, which stretches farther south than Sápmi. North Sami, Skolt Sami, and Aanaar Sami are indigenous to the region.

Four municipalities in the northern part of Finnish Lapland constitute the Sami Domicile Area, Sámiid Ruovttoguovlu, a region that is autonomous on issues regarding Sami culture and language.

Coats of Arms of Sami Communities

- Coats of Arms

Romsa ja Finnmárku

Romsa ja Finnmárku

(Norway) Nordland

Nordland

(Norway) Trööndelage

Trööndelage

(Norway) Lapplánda

Lapplánda

(Sweden) Norrbottena

Norrbottena

(Sweden) Västerbottena

Västerbottena

(Sweden) Jämtlándda

Jämtlándda

(Sweden) Härjedaelie

Härjedaelie

(Sweden) Lappi

Lappi

(Finland) Murmánska

Murmánska

(Russia)

Sports

The region has its own football team, the Sápmi football team, which is organized by FA Sápmi. It is a member of ConIFA and the host of 2014 ConIFA World Football Cup. Sápmi football team won the 2006 VIVA World Cup and hosted the 2008 event.

The Tour de Barents is a cross-country skiing race held in the region.

Notable places

The following towns and villages have a significant Sami population or host Sami institutions. Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, or Russian toponyms are in parentheses.

North Sámi area

- Deatnu (Tana) has a significant Sami population.

- Divtasvuodna (Tysfjord) is a centre for the Lule (Julev) Sami population. The Árran Lule-Sami centre is here.

- Eanodat (Enontekiö).

- Gáivuotna (Kåfjord) is an important centre for the Coastal Sami culture, which is host to the Riddu Riđđu international indigenous festival each summer. The municipality has a Sami language centre, and hosts the Ája Sami Centre. The opposition against Sami language and culture revitalization in Gáivuotna was infamous in the late 1990s and included Sami language road signs being shot to pieces repeatedly.

- Giron (Kiruna) is the seat of the Swedish Sami Parliament and the largest urban settlement in Swedish Lapland.

- Guovdageaidnu (Kautokeino): About 90% of the population speak North Sami, and several Sami institutions are here. These include: Beaivváš Sami Theatre, a Sami High School and Reindeer Herding School, the Sami University College, the Nordic Sami Research Institute, the Sami Language Board, the Resource Centre for the Rights of Indigenous People, and the International Centre For Reindeer Husbandry. In addition, several Sami media are based in Kautokeino. These include the Sami language newspaper Áššu and the DAT Sami publishing house/record company. Kautokeino also hosts the Sami Easter Festival. The Kautokeino rebellion in 1852 is one of the few Sami rebellions against the Norwegian government's oppression against the Sami.

- Jiellevárri or Váhčir (Gällivare)

- Johkamohkki (Jokkmokk) holds a large Sami market and festival the first weekend of every February. It is also the location of Ájtte, Svenskt fjäll- och samemuseum.

- Kárášjohka (Karasjok) is the seat of the Norwegian Sami Parliament. Also other important Sami institutions including NRK Sami Radio, the Sami Collections museum, the Sami Art Centre, the Sami Specialist Library, the legal office of Middle Finnmark, the Inner Finnmark Child and Youth Psychiatric Policlinic, the Sami Specialist Medical Centre, and the Sami Health Research Institute. In addition, the Sápmi cultural park is in the township, and the Sami language Min Áigi newspaper is published here.

- Leavdnja (Lakselv) in Porsáŋgu (Porsanger) municipality is the location of the Finnmark Estate, and the Ságat Sami newspaper. The Finnmarkseiendommen organization owns and manages about 95% of the land in Finnmark, and 50% of its board members are elected by the Norwegian Sami Parliament.

- Ohcejohka (Utsjoki).

- Romsa or Tromsa (Tromsø) is the largest city in the Central Sami area and has a university that specializes in Sami subjects. It also has a notable and very active Sami population.

- Unjárga (Nesseby) is an important centre for the Coastal Sami culture. It is also the site for the Várjjat Sami Museum and the Norwegian Sami Parliament's department of culture and environment. The first Sami to be elected into the Norwegian Parliament, Isak Saba, was born here.

South Sápmi

- Aarborte (Hattfjelldal) is a southern Sami centre with a southern-Sami language school and a Sami culture centre.

- Arjeplog.

- Snåase (Snåsa) is a centre for the Southern Sami language, and the only municipality in Norway where Southern Sami is an official language. The Saemien Sijte southern Sami museum is in Snåase.

East Sápmi

- Aanaar, Anár, or Aanar (Inari) is the seat of the Finnish Sami Parliament

- Lujávri (Lovozero) is the largest settlement of Sami on the Russian side.

See also

- Cuisine of Lapland

- Environmental racism in Europe

- Inari

- Laestadian

- Lapland War

- Laponian area—a UNESCO World Heritage site protecting the Sami homelands in Sweden

- Nordic countries

References

Notes

- Estimates of people who identify as Sámi in the four countries vary between 50,000 and 100,000, out of 2,000,000 in the region; the higher estimates tend to include people who are also part of their country's majority people, on account of for example a great-grandparent who was Sámi.

Citations

- Riitta-Liisa, Valijärvi (2017). North Sámi : an essential grammar. Kahn, Lily. Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 9781138839373. OCLC 974612447.

- "Lapland." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009. Web. 24 November 2009 http://search.eb.com/eb/article-9047170.

- We are the Sámi – Fact sheets. Gáldu Resource Centre for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

- Anderson, Myrdene (November 1983). "The Saami People of Lapland: Four Recent Works on the Interplay of History, Ethnicity and Reindeer Pastoralism". Nomadic Peoples. 14 (14): 57–58. JSTOR 43123201.; "The Lapp or Sami people". Yokmok. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

At present, the Scandinavian media use no other term than Sámis. Institutions and the media use the word Sámi. The term “lapp” is considered pejorative.

; "Saamis or Lapps". SURI. Retrieved 26 December 2019.They call themselves saam´ or saam´lja (on the Kola Peninsula), sabme, sabmelas^ (pl. sabmela at). Other nations have called them Fenn (Finn) and since the 12th century, Lapp (e.g. the form Lop’ appears in Old Russian Chronicles at about 1000 AD). The use of the name Saam has been propagated in Russia since the 1920s and in Scandinavia within the last decades. The Saamis themselves consider the name Lapp pejorative.

- Article on the subject by the Finno-Ugrian Society.

- Egil's Saga, Chapter XIV

- Rapp, Ole Magnus; Stein, Catherine (8 February 2008). "Samis don't want to be 'Lapps'". Aftenposten. Archived from the original on 15 March 2008.

- The History of Lapland: Chap. I: Of the name of Lapland, Scheffer, John, Oxford, 1674

- Svanberg, Jons (1805). Exposition des opérations faites en Lapponie, pour la détermination d'un arc du méridien en 1801, 1802 et 1803 (in French). Johan Pehr Lindh.

- Presentation of Finnmark by Norway's Ministry of Trade and Industry Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine in their official travel guide to Norway.

- http://www.samiculturalcenter.org/

- "RUSSLAND: Samene vil ha et eget Sameting". Galdu.org. 14 December 2008. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- Samiskt parlamentariskt råd – Sametinget

- "Президент России принял отставку губернатора Мурманской области Марины Ковтун, временно исполняющим обязанности главы региона назначен Андрей Чибис" (in Russian). Government of Murmansk Oblast. 21 March 2019.

- Korsrud Nordlands første, NRK, Retrieved 31 July 2008

External links

Works written on the topic Lapland at Wikisource

Works written on the topic Lapland at Wikisource