Salmon run

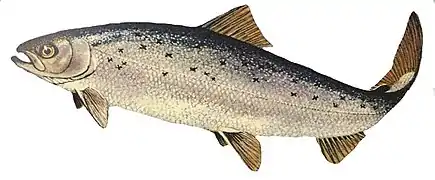

The salmon run is the time when salmon, which have migrated from the ocean, swim to the upper reaches of rivers where they spawn on gravel beds. After spawning, all Pacific salmon and most Atlantic salmon[1] die, and the salmon life cycle starts over again. The annual run can be a major event for grizzly bears, bald eagles and sport fishermen. Most salmon species migrate during the fall (September through November).[2]

.jpg.webp)

Most salmon mostly spend their early life in rivers or lakes, and then swim out to sea where they live their adult lives and gain most of their body mass. When they have matured, they return to the rivers to spawn. There are populations of some salmon species that spend their entire life in freshwater. Usually they return with uncanny precision to the natal river where they were born, and even to the very spawning ground of their birth. It is thought that, when they are in the ocean, they use magnetoreception to locate the general position of their natal river, and once close to the river, that they use their sense of smell to home in on the river entrance and even their natal spawning ground.

In northwest America, salmon is a keystone species, which means the impact they have on other life is greater than would be expected in relation to their biomass. The death of the salmon has important consequences, since it means significant nutrients in their carcasses, rich in nitrogen, sulfur, carbon and phosphorus, are transferred from the ocean to terrestrial wildlife such as bears and riparian woodlands adjacent to the rivers. This has knock-on effects not only for the next generation of salmon, but to every species living in the riparian zones the salmon reach.[3] The nutrients can also be washed downstream into estuaries where they accumulate and provide much support for estuarine breeding birds.

Background

Most salmon are anadromous, a term which comes from the Greek anadromos, meaning "running upward".[4] Anadromous fish grow up mostly in the saltwater in oceans. When they have matured they migrate or "run up" freshwater rivers to spawn in what is called the salmon run.[5]

Anadromous salmon are Northern Hemisphere fish that spend their ocean phase in either the Atlantic Ocean or the Pacific Ocean. They do not thrive in warm water. There is only one species of salmon found in the Atlantic, commonly called the Atlantic salmon. These salmon run up rivers on both sides of the ocean. Seven different species of salmon inhabit the Pacific (see table), and these are collectively referred to as Pacific salmon. Five of these species run up rivers on both sides of the Pacific, but two species are found only on the Asian side.[6] In the early 19th century, Chinook salmon were successfully established in the Southern Hemisphere, far from their native range, in New Zealand rivers. Attempts to establish anadromous salmon elsewhere have not succeeded.[7]

Species of anadromous salmon Oceans Coasts Species[6] Maximum Comment length weight life span North Atlantic Both sides Atlantic salmon[8] 150 cm 46.8 kg 13 years North Pacific Both sides Chinook salmon[9] 150 cm 61.4 kg 9 years Also established in New Zealand Chum salmon[10] 100 cm 15.9 kg 7 years Coho salmon[11] 108 cm 15.2 kg 5 years Pink salmon[12] 76 cm 6.8 kg 3 years Sockeye salmon[13] 84 cm 7.7 kg 8 years Asian side Masu salmon[14] 79 cm 10.0 kg Biwa salmon[15] 44 cm 1.3 kg

The life cycle of an anadromous salmon begins and, if it survives the full course of its natural life, usually ends in a gravel bed in the upper reaches of a stream or river. These are the salmon spawning grounds where salmon eggs are deposited, for safety, in the gravel. The salmon spawning grounds are also the salmon nurseries, providing a more protected environment than the ocean usually offers. After 2 to 6 months the eggs hatch into tiny larvae called sac fry or alevin. The alevin have a sac containing the remainder of the yolk, and they stay hidden in the gravel while they feed on the yolk. When the yolk has gone they must find food for themselves, so they leave the protection of the gravel and start feeding on plankton. At this point the baby salmon are called fry. At the end of the summer the fry develop into juvenile fish called parr. Parr feed on small invertebrates and are camouflaged with a pattern of spots and vertical bars. They remain in this stage for up to three years.[16][17]

As they approach the time when they are ready to migrate out to the sea the parr lose their camouflage bars and undergo a process of physiological changes which allows them to survive the shift from freshwater to saltwater. At this point salmon are called smolt. Smolt spend time in the brackish waters of the river estuary while their body chemistry adjusts their osmoregulation to cope with the higher salt levels they will encounter in the ocean.[18] Smolt also grow the silvery scales which visually confuse ocean predators. When they have matured sufficiently in late spring, and are about 15 to 20 centimetres long, the smolt swim out of the rivers and into the sea. There they spend their first year as a post-smolt. Post-smolt form schools with other post-smolt, and set off to find deep-sea feeding grounds. They then spend up to four more years as adult ocean salmon while their full swimming ability and reproductive capacity develop.[16][17][18]

Then, in one of the animal kingdom's more extreme migrations, the salmon return from the saltwater ocean back to a freshwater river to spawn afresh.[19]

Return from the ocean

After several years wandering huge distances in the ocean, most surviving salmon return to the same natal rivers where they were spawned. Then most of them swim up the rivers until they reach the very spawning ground that was their original birthplace.[20]

There are various theories about how this happens. One theory is that there are geomagnetic and chemical cues which the salmon use to guide them back to their birthplace. The fish may be sensitive to the Earth's magnetic field, which could allow the fish to orient itself in the ocean, so it can navigate back to the estuary of its natal stream.[21]

Salmon have a strong sense of smell. Speculation about whether odours provide homing cues go back to the 19th century.[22] In 1951, Hasler hypothesised that, once in vicinity of the estuary or entrance to its birth river, salmon may use chemical cues which they can smell, and which are unique to their natal stream, as a mechanism to home onto the entrance of the stream.[23] In 1978, Hasler and his students convincingly showed that the way salmon locate their home rivers with such precision was indeed because they could recognise its characteristic smell. They further demonstrated that the smell of their river becomes imprinted in salmon when they transform into smolts, just before they migrate out to sea.[20][24][25] Homecoming salmon can also recognise characteristic smells in tributary streams as they move up the main river. They may also be sensitive to characteristic pheromones given off by juvenile conspecifics. There is evidence that they can "discriminate between two populations of their own species".[20][26]

The recognition that each river and tributary has its own characteristic smell, and the role this plays as a navigation aid, led to a widespread search for a mechanism or mechanisms that might allow salmon to navigate over long distances in the open ocean. In 1977, Leggett identified, as mechanisms worth investigating, the use of the sun for navigation, and orientation to various possible gradients, such as temperature, salinity or chemicals gradients, or geomagnetic or geoelectric fields.[27][28]

There is little evidence salmon use clues from the sun for navigation. Migrating salmon have been observed maintaining direction at nighttime and when it is cloudy. Likewise, electronically tagged salmon were observed to maintain direction even when swimming in water much too deep for sunlight to be of use.[29]

In 1973, it was shown that Atlantic salmon have conditioned cardiac responses to electric fields with strengths similar to those found in oceans. "This sensitivity might allow a migrating fish to align itself upstream or downstream in an ocean current in the absence of fixed references."[30] In 1988, researchers found iron, in the form of single domain magnetite, resides in the skulls of sockeye salmon. The quantities present are sufficient for magnetoception.[31]

Tagging studies have shown a small number of fish don't find their natal rivers, but travel instead up other, usually nearby streams or rivers.[32][33] It is important some salmon stray from their home areas; otherwise new habitats could not be colonized. In 1984, Quinn hypothesized there is a dynamic equilibrium, controlled by genes, between homing and straying.[34] If the spawning grounds have a uniform high quality, then natural selection should favour the descendants that home accurately. However, if the spawning grounds have a variable quality, then natural selection should favour a mixture of the descendants that stray and the descendants that home accurately.[21][34]

Prior to the run up the river, the salmon undergo profound physiological changes. Fish swim by contracting longitudinal red muscle and obliquely oriented white muscles. Red muscles are used for sustained activity, such as ocean migrations. White muscles are used for bursts of activity, such as bursts of speed or jumping.[35] As the salmon comes to end of its ocean migration and enters the estuary of its natal river, its energy metabolism is faced with two major challenges: it must supply energy suitable for swimming the river rapids, and it must supply the sperm and eggs required for the reproductive events ahead. The water in the estuary receives the freshwater discharge from the natal river. Relative to ocean water, this has a high chemical load from surface runoff. Researchers in 2009 found evidence that, as the salmon encounter the resulting drop in salinity and increase in olfactory stimulation, two key metabolic changes are triggered: there is a switch from using red muscles for swimming to using white muscles, and there is an increase in the sperm and egg load. "Pheromones at the spawning grounds [trigger] a second shift to further enhance reproductive loading."[36]

The salmon also undergo radical morphological changes as they prepare for the spawning event ahead. All salmon lose the silvery blue they had as ocean fish, and their colour darkens, sometimes with a radical change in hue. Salmon are sexually dimorphic, and the male salmon develop canine-like teeth and their jaws develop a pronounced curve or hook (kype). Some species of male salmon grow large humps.[37]

Obstacles to the run

Salmon start the run in peak condition, the culmination of years of development in the ocean. They need high swimming and leaping abilities to battle the rapids and other obstacles the river may present, and they need a full sexual development to ensure a successful spawn at the end of the run. All their energy goes into the physical rigours of the journey and the dramatic morphological transformations they must still complete before they are ready for the spawning events ahead.

The run up the river can be exhausting, sometimes requiring the salmon to battle hundreds of miles upstream against strong currents and rapids. They cease feeding during the run.[5] Chinook and sockeye salmon from central Idaho must travel 900 miles (1,400 km) and climb nearly 7,000 feet (2,100 m) before they are ready to spawn. Salmon deaths that occur on the upriver journey are referred to as en route mortality.[38]

Salmon negotiate waterfalls and rapids by leaping or jumping. They have been recorded making vertical jumps as high as 3.65 metres (12 ft).[39] The height that can be achieved by a salmon depends on the position of the standing wave or hydraulic jump at the base of the fall, as well as how deep the water is.[39]

Fish ladders, or fishways, are specially designed to help salmon and other fish to bypass dams and other man-made obstructions, and continue on to their spawning grounds further upriver.[40] Data suggest that navigation locks have a potential to be operated as vertical slot fishways to provide increased access for a range of biota, including poor swimmers.[41]

Skilled predators, such as bears, bald eagles and fishermen can await the salmon during the run. Normally solitary animals, grizzly bears congregate by streams and rivers when the salmon spawn.[3][42] Predation from Harbor seals, California sea lions, and Steller sea lions, can pose a significant threat, even in river ecosystems.[43][44]

Black bears also fish the salmon. Black bears usually operate during the day, but when it comes to salmon they tend to fish at night.[45] This is partly to avoid competition with the more powerful brown bears, but it is also because they catch more salmon at night.[46] During the day, salmon are very evasive and attuned to visual clues, but at night they focus on their spawning activities, generating acoustic clues the bears tune into.[45] Black bears may also fish for salmon during the night because their black fur is easily spotted by salmon in the daytime. In 2009, researchers compared the foraging success of black bears with the white-coated Kermode bear, a morphed subspecies of the black bear. They found the Kermode bear had no more success catching salmon at night time, but had greater success than the black bears during the day.[47]

Otters are also common predators. In 2011, researchers showed that when otters predate salmon, the salmon can "sniff them out". They demonstrated that once otters have eaten salmon, the remaining salmon could detect and avoid the waters where otter faeces was present.[48][49]

The spawning

The term prespawn mortality is used to refer to fish that arrive successfully at the spawning grounds, and then die without spawning. Prespawn mortality is surprisingly variable, with one study observing rates between 3% and 90%.[38][50] Factors that contribute to these mortalities include high temperatures,[51][52] high river discharge rates,[53] and parasites and diseases.[50][54] However, "at present there are no reliable indicators to predict whether an individual arriving at a spawning area will in fact survive to spawn."[38]

The eggs of a female salmon are called her roe. To lay her roe, the female salmon builds a spawning nest, called a redd, in a riffle with gravel as its streambed. A riffle is a relatively shallow length of stream where the water is turbulent and flows faster. She builds the redd by using her tail (caudal fin) to create a low-pressure zone, lifting gravel to be swept downstream, and excavating a shallow depression. The redd may contain up to 5,000 eggs, each about the size of a pea, covering 30 square feet (2.8 m2).[55] The eggs usually range from orange to red. One or more males will approach the female in her redd, depositing his sperm, or milt, over her eggs.[56] The female then covers the eggs by disturbing the gravel at the upstream edge of the depression before moving on to make another redd. The female will make as many as seven redds before her supply of eggs is exhausted.[56][57]

Male pink salmon and some sockeye salmon develop pronounced humps just before they spawn. These humps may have evolved because they confer species advantages. The humps make it less likely the salmon will spawn in the shallow water at margins of the streambed, which tend to dry out during low water flows or freeze in winter. Further, riffles can contain many salmon spawning simultaneously, as in the image on the right. Predators, such as bears, will be more likely to catch the more visually prominent humped males, with their humps projecting above the surface of the water. This may provide a protective buffer for the females.[58]

Dominant male salmon defend their redds by rushing at and chasing intruders. They butt and bite them with the canine-like teeth they developed for the spawning event. The kypes are used to clamp around the base of the tail (caudal peduncle) of an opponent.[58]

The condition of the salmon deteriorates the longer they remain in fresh water. Once the salmon have spawned, most of them deteriorate rapidly and die. This programmed senescence is "characterized by immunosuppression and organ deterioration."[38][59][60] The Pacific salmon is the classic example of a semelparous animal. It lives for many years in the ocean before swimming to the freshwater stream of its birth, spawning, and then dying. Semelparous animals spawn once only in their lifetime. Semelparity is sometimes called "big bang" reproduction, since the single reproductive event of semelparous organisms is usually large and fatal to the spawners.[61] Most Atlantic salmon also die after spawning, but not all. About 5 to 10%, mostly female, return to the ocean where they can recover and spawn again.[18]

Keystone species

In the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, salmon is a keystone species, supporting wildlife from birds to bears and otters.[62] The bodies of salmon represent a transfer of nutrients from the ocean, rich in nitrogen, sulfur, carbon and phosphorus, to the forest ecosystem.

Grizzly bears function as ecosystem engineers, capturing salmon and carrying them into adjacent wooded areas. There they deposit nutrient-rich urine and faeces and partially eaten carcasses. It has been estimated that bears leave up to half the salmon they harvest on the forest floor,[63][64] in densities that can reach 4,000 kilograms per hectare,[65] providing as much as 24% of the total nitrogen available to the riparian woodlands.[3] The foliage of spruce trees up to 500 m (1,600 ft) from a stream where grizzlies fish salmon have been found to contain nitrogen originating from fished salmon.[3]

Wolves normally hunt for deer. However, a 2008 study shows that, when the salmon run starts, the wolves choose to fish for salmon, even if plenty of deer are still available.[67] "Selecting benign prey such as salmon makes sense from a safety point of view. While hunting deer, wolves commonly incur serious and often fatal injuries. In addition to safety benefits we determined that salmon also provides enhanced nutrition in terms of fat and energy."[66]

The upper reaches of the Chilkat River in Alaska has particularly good spawning grounds. Each year these attract a run of up to half a million chum salmon. As the salmon run up the river, bald eagles arrive in their thousands to feast at the spawning grounds. This results in some of the world's largest congregations of bald eagles. The number of participating eagles is directly correlated with the number of spawning salmon.[68]

Residual nutrients from salmon can also accumulate downstream in estuaries. A 2010 study showed the density and diversity of many estuarine breeding birds in the summer "were strongly predicted by salmon biomass in the autumn."[69] Anadromous salmon provide nutrients to these "diverse assemblages ... ecologically comparable to the migrating herds of wildebeest in the Serengeti".[65]

Prospects

The future of salmon runs worldwide depends on many factors, most of which are driven by human actions. Among the key driving factors are (1) harvest of salmon by commercial, recreational, and subsistence fishing, (2) alterations in stream and river channels, including construction of dikes and other riparian corridor modifications, (3) electricity generation, flood control, and irrigation supplied by dams, (4) alteration by humans of freshwater, estuarine, and marine environments used by salmon, coupled with aquatic changes due to climate and ocean circulatory regimes, (5) water withdrawals from rivers and reservoirs for agricultural, municipal, or commercial purposes, (6) changes in climate caused at least in part by human activities, (7) competition from non-native fishes, (8) salmon predation by marine mammals, birds, and other fish species, (9) diseases and parasites, including those from outside the native region, and (10) reduced nutrient replenishment from decomposing salmon.[70]

In 2009, NOAA advised that continued runoff into North American rivers of three widely used pesticides containing neurotoxins will "jeopardize the continued existence" of endangered and threatened Pacific salmon.[71][72] Global warming could see the end of some salmon runs by the end of the century, such as the Californian runs of Chinook salmon.[73][74] A 2010 United Nations report says increases in acidification of oceans means shellfish such as pteropods, an important component of the ocean salmon diet, are finding it difficult to build their aragonite shells.[75] There are concerns that this too may endanger future salmon runs.[76]

Notable runs

| External video | |

|---|---|

- Adams River (British Columbia)

- Chilkat River (Alaska)

- Columbia River (British Columbia, United States)

- Copper River (Alaska)

- Fraser River (British Columbia)

- Kenai River (Alaska)

- River Spey (Scotland)

- River Tay (Scotland)

- River Tweed (border of Scotland and England)

- River Tyne (England)

- Snake River (United States)

- Yukon River (Alaska, Yukon, British Columbia)

See also

References

- Atlantic salmon, Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- "Questions and Answers About Salmon". Western Fisheries Research Center. U.S. Geological Survey.

- Helfield, J. & Naiman, R. (2006), "Keystone Interactions: Salmon and Bear in Riparian Forests of Alaska" (PDF), Ecosystems, 9 (2): 167–180, doi:10.1007/s10021-004-0063-5

- "Anadromous". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- Moyle, p. 188

- NOAA (2011) NEFSC Fish FAQ Archived 2012-01-04 at the Wayback Machine NOAA Fisheries Service. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- Walrond C (2010) Trout and salmon – Chinook salmon Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated 9 September 2010.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). "Salmo salar" in FishBase. December 2011 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). "Oncorhynchus tshawytscha" in FishBase. December 2011 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). "Oncorhynchus keta" in FishBase. December 2011 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). "Oncorhynchus kisutch" in FishBase. December 2011 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). "Oncorhynchus gorbuscha" in FishBase. December 2011 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). "Oncorhynchus nerka" in FishBase. December 2011 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011h). "Oncorhynchus masou" in FishBase. December 2011h version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). "Oncorhynchus rhodurus" in FishBase. December 2011 version.

- Bley, Patrick W and Moring, John R (1988) Freshwater and Ocean Survival of Atlantic Salmon and Steelhead: A Synopsis" US Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Lindberg, Dan-Erik (2011) Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) migration behavior and preferences in smolts, spawners and kelts Introductory Research Essay, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

- Atlantic Salmon Trust Salmon Facts Archived 2011-11-30 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- Crossin, G. T.; Hinch, S. G.; Cooke, S. J.; Cooperman, M. S.; Patterson, D. A.; Welch, D. W.; Hanson, K. C.; Olsson, I; English, K. K.; Farrell, A. P. (2009). "Mechanisms Influencing the Timing and Success of Reproductive Migration in a Capital Breeding Semelparous Fish Species, the Sockeye Salmon" (PDF). Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 82 (6): 635–52. doi:10.1086/605878. PMID 19780650. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-04-26.

- Moyle, p. 190

- Lohmann K, Putnam N, Lohmann C (2008). "Geomagnetic imprinting: a unifying hypothesis of long-distance natal homing in salmon and sea turtles". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (49): 19096–19101. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801859105. PMC 2614721. PMID 19060188.

- Trevanius GR (1822) Biologie oder Philosophic der lebenden Natur fur Naturforscher und Arzte, vol VI Rower, Gottingen.

- Hasler AD (1951). "Discrimination of stream odors by fishes and its relation to parent stream behavior". American Naturalist. 85 (823): 223–238. doi:10.1086/281672. JSTOR 2457678.

- Hasler AD and Scholtz AT (1978) "Olfactory imprinting and homing in salmon: Investigations into the mechanism of the imprinting process, pp. 356-369 in Animal migration, navigation, and homing, Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-08777-9.

- Dittman A, Quinn T (1996). "Homing in Pacific salmon: mechanisms and ecological basis". Journal of Experimental Biology. 199 (Pt 1): 83–91. PMID 9317381.

- Groot C, Quinn TP, Hara TJ (1986). "Responses of migrating adult sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) to population-specific odours". Can. J. Zool. 64 (4): 926–932. doi:10.1139/z86-140.

- Leggett WC (1977). "The ecology of fish migrations" (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 8: 285–308. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.08.110177.001441. JSTOR 2096730. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-06.

- Moyle, p. 191

- Ogura M, Ishida Y (1995). "Homing behavior and vertical movements of four species of Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) in the central Bering Sea". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 52 (3): 532–540. doi:10.1139/f95-054.

- Rommel SA, McCleave JD (1973). "Sensitivity of American Eels (Anguilla rostrata) and Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) to Weak Electric and Magnetic Fields". Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. 30 (5): 657–663. doi:10.1139/f73-114.

- Walker MM, Quinn TP, Kirschvink JL, Groot C (1988). "Production of single-domain magnetite throughout life by sockeye salmon, Oncorhynchus nerka" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 140: 51–63. PMID 3204338.

- Quinn TP, Nemeth RS, McIsaac DO (1991). "Homing and straying patterns of fall chinook salmon in the lower Columbia River". Trans Am Fish Soc. 120 (2): 150–156. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1991)120<0150:HASPOF>2.3.CO;2.

- Tallman RF, Healey MC (1994). "Homing, straying, and gene flow among seasonally separated populations of chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta)". Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 51 (3): 577–588. doi:10.1139/f94-060.

- Quinn TP (1984) "Mechanisms of Migration in Fishes Eds: McCleave JD, Arnold GP, Dodson JJ, Neill WH, pp. 357–362. Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-41676-7.

- Kapoor BG and Khanna B (2004) Ichthyology handbook. Springer. pp. 137–140. ISBN 978-3-540-42854-1.

- Miller KM, Schulze AD, Ginther N, Li S, Patterson DA, Farrell AP, Hinch SG (2009). "Salmon spawning migration: metabolic shifts and environmental triggers" (PDF). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology D. 4 (2): 75–89. doi:10.1016/j.cbd.2008.11.002. PMID 20403740.

- Department of Fish and Wildlife (2011) Salmon and steelhead life cycle and habitat information Washington. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- Jeffries KM, SG Hinch SG, MR Donaldson MR, Gale MK, Burt JM, Thompson LA, Farrell AP, Patterson DA, Miller KM (2011). "Temporal changes in blood variables during final maturation and senescence in male sockeye salmon Oncorhynchus nerka: reduced osmoregulatory ability can predict mortality" (PDF). Journal of Fish Biology. 79 (2): 449–65. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2011.03042.x. PMID 21781102.

- Beach MH (1984). "Fish pass design - criteria for the design and approval of fish passes and other structures to facilitate the passage of migratory fish in rivers" (PDF). Fish Res Tech Rep. 78: 1–46.

- Michigan DNR. What is a Fish Ladder? Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- Silva, Sergio; Lowry, Maran; Macaya-Solis, Consuelo; Byatt, Barry; Lucas, Martyn C. (2017). "Can navigation locks be used to help migratory fishes with poor swimming performance pass tidal barrages? A test with lampreys". Ecological Engineering. 102: 291–302. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2017.02.027.

- Hilderbrand, G.; Hanley, T.; Robbins, C. & Schwartz, C. (1999). "Role of Brown Bears (Ursus arctos) in the Flow of Marine Nitrogen into a Terrestrial Ecosystem". Oecologia. 121 (4): 546–550. Bibcode:1999Oecol.121..546H. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.160.450. doi:10.1007/s004420050961. PMID 28308364.

- Seal & Sea Lion Facts of the Columbia River & Adjacent Nearshore Marine Areas (PDF), NOAA, March 2008, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-23, retrieved 2012-04-16

- "Endangered Seals Eating Endangered Salmon", Bryant Park Project, NPR, May 6, 2008

- Klinka DR, Reimchen TE (2009). "Darkness, twilight, and daylight foraging success of bears (Ursus Americanus) on salmon in coastal British Columbia" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 90: 144–149. doi:10.1644/07-MAMM-A-200.1.

- Reimchen TE (2009). "Nocturnal foraging behaviour of black bears Ursus americanus on Moresby Island British Columbia" (PDF). Canadian Field-Naturalist. 112: 446–450.

- Klinka DR, Reimchen TE (2009). "Adaptive coat colour polymorphism in the Kermode bear of coastal British Columbia" (PDF). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 98 (3): 479–488. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01306.x.

- Roberts LJ, de Leaniz CG (2011). "Something smells fishy: predator-naive salmon use diet cues, not kairomones, to recognize a sympatric mammalian predator". Animal Behaviour. 82 (4): 619–625. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.06.019.

- PlanetEarth (12 September 2011). Salmon can sniff out predators Archived 2011-10-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- Gilhousen P (1990) Prespawning mortalities of sockeye salmon in the Fraser River system and possible causal factors International Pacific Salmon Fisheries Commission, Bulletin 26, 1–58.

- Crossin GT, Hinch SG, Cooke SJ, Welch DW, Patterson DA, Jones SR, Lotto AG, Leggatt RA, Mathes MT, Shrimpton JM, Van der Kraak G, Farrell AP (2008). "Exposure to high temperature influences the behaviour, physiology, and survival of sockeye salmon during spawning migration" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Zoology. 86 (2): 127–140. doi:10.1139/Z07-122.

- Farrell AP, Hinch SG, Cooke SJ, Patterson DA, Crossin GT, Lapointe M, Mathes MT (2008). "Pacific salmon in hot water: applying metabolic scope models and biotemetry to predict the success of spawning migrations". Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 81 (6): 697–708. doi:10.1086/592057. PMID 18922081.

- Rand PS, Hinch SG, Morrison J, Foreman MG, MacNutt MJ, Macdonald JS, Healey MC, Farrell AP, Higgs DA (2006). "Effects of river discharge, temperature, and future climates on energetics and mortality of adult migrating Fraser River sockeye salmon" (PDF). Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 135 (3): 655–667. doi:10.1577/T05-023.1.

- Jones SR, Prosperi-Porta G, Dawe SC, Barnes DP (2003). "Distribution, prevalence and severity of Parvicapsula minibicornis infections among anadromous salmonids in the Fraser River, British Columbia, Canada" (PDF). Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 54 (1): 49–54. doi:10.3354/dao054049. PMID 12718470.

- McGrath, Susan. "Spawning Hope". Audubon Society. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- Fish and Wildlife Services (2011) Pacific Salmon, (Oncorhynchus spp.) U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services. Accessed: 28 December 2011.

- Department of Fish and Wildlife (2011) What is a redd? Washington. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- Groot C and Margolis L (1991) Pacific salmon life histories. UBC Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7748-0359-5.

- Dickhoff WW (1989) "Salmonids and annual fishes: death after sex" Pages 253–266. In: Schreibman MP and Scanes C G (eds) Development, maturation, and senescence of neuroendocrine systems, University of California. ISBN 978-0-12-629060-8.

- Finch CE (1990) Longevity, Senescence, and the Genome University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-24889-9.

- Ricklefs RE and Miller GK (2000) Ecology W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-2829-0.

- Willson MF, Halupka KC (1995). "Anadromous Fish as Keystone Species in Vertebrate Communities" (PDF). Conservation Biology. 9 (3): 489–497. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1995.09030489.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-11-28.

- Reimchen TE (2001). "Salmon nutrients, nitrogen isotopes and coastal forests" (PDF). Ecoforestry. 16: 13.

- Quinn, T.; Carlson, S.; Gende, S. & Rich, H. (2009). "Transportation of Pacific Salmon Carcasses from Streams to Riparian Forests by Bears" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Zoology. 87 (3): 195–203. doi:10.1139/Z09-004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-06-16.

- Reimchen TE, Mathewson DD, Hocking MD, Moran J (2002). "Isotopic evidence for enrichment of salmon-derived nutrients in vegetation, soil, and insects in riparian zones in coastal British Columbia" (PDF). American Fisheries Society Symposium. 20: 1–12.

- ScienceDaily (1 September 2008) Wolves Would Rather Eat Salmon.

- Darimont CT, Paquet PC, Reimchen TE (2008). "Spawning salmon disrupt trophic coupling between wolves and ungulate prey in coastal British Columbia". BMC Ecology. 8: 14. doi:10.1186/1472-6785-8-14. PMC 2542989. PMID 18764930.

- Hansen A, EL Boeker EL and Hodges JI (2010) "The Population Ecology of Bald Eagles Along the Pacific Northwest Coast" Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 117–133 in PF Schempf and BA Wright, Bald Eagles in Alaska, Hancock House Pub. ISBN 978-0-88839-695-2.

- Field RD, Reynolds JD (2011). "Sea to sky: impacts of residual salmon-derived nutrients on estuarine breeding bird communities" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1721): 3081–3088. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2731. PMC 3158931. PMID 21325324. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-04.

- Stouder, Deanna J. (1997). Pacific Salmon & Their Ecosystems : Status and Future Options. Bisson, Peter A., Naiman, Robbert J., Duke, Marcus G. Boston, MA: Springer US. ISBN 978-1-4615-6375-4. OCLC 840286102.

- NOAA (2009) [ Registration of Pesticides Containing Carbaryl, Carbofuran, and Methomyl] Biological Opinion, National Marine Fisheries Service.

- Environment News Service (21 April 2009) Three Common Pesticides Toxic to Salmon.

- Thompson LC, Escobar MI, Mosser CM, Purkey DR, Yates D, Moyle PB (2012). "Water Management Adaptations to Prevent Loss of Spring-Run Chinook Salmon in California under Climate Change". Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management. 138 (5): 465–478. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)WR.1943-5452.0000194.

- ScienceDaily (1 September 2011) Warming Streams Could Be the End for Spring-Run Chinook Salmon in California.

- UNEP (2010) Environmental Consequences of Ocean Acidification: A Threat to Food Security

- The Telegraph (3 December 2010). Cancun climate summit: Britain's salmon at risk from ocean acidification.

Cited sources

- Moyle PB, Cech JJ (2004). Fishes, An Introduction to Ichthyology (5th ed.). Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-13-100847-2.

Further reading

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). "Oncorhynchus mykiss" in FishBase. December 2011 version.

- USDA Forest Service, Salmon/Steelhead Pacific Northwest Fisheries Program. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- Knapp G, Roheim CA and Anderson JL (2007) The Great Salmon Run: Competition Between Wild and Farmed Salmon World Wildlife Fund.

- Mozaffari, Ahmad and Alireza Fathi (2013) "A natural-inspired optimization machine based on the annual migration of salmons in nature" arXiv:1312.4078.

- Quinn, Thomas P. (2005) The Behavior and Ecology of Pacific Salmon and Trout UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-1128-6.

- Magnetoception and natal homing

- Bandoh H, Kida I, Ueda H (2011). "Olfactory Responses to Natal Stream Water in Sockeye Salmon by BOLD fMRI". PLoS ONE. 6 (1): e16051. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...616051B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016051. PMC 3022028. PMID 21264223.

- Bracis, Chloe (2010) A model of the ocean migration of Pacific salmon University of Washington.

- Johnsen S, Lohmann KJ (2005). "The physics and neurobiology of magnetoreception" (PDF). Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 6 (9): 703–712. doi:10.1038/nrn1745. PMID 16100517. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-30.

- Johnsen S, Lohmann KJ (2008). "Magnetoreception in animals" (PDF). Physics Today. 61 (3): 29–35. Bibcode:2008PhT....61c..29J. doi:10.1063/1.2897947. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-30.

- Lohmann KJ, Lohmann CM, Endres CS (2008). "The sensory ecology of ocean navigation". J Exp Biol. 211 (11): 1719–1728. doi:10.1242/jeb.015792. PMID 18490387.

- Mann S, Sparks NH, Walker MM, Kirschvink JL (1988). "Ultrastructure, morphology and organization of biogenic magnetite from sockeye salmon, Oncorhynchus nerka: implications for magnetoreception" (PDF). J Exp Biol. 140: 35–49. PMID 3204335.

- Metcalfe J, Arnold G and McDowall R (2008) "Migration" pp. 175–199. In: John D. Reynolds, Handbook of fish biology and fisheries, Volume 1, John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-632-05412-1.

- Moore A, Privitera L and Riley WD (2013) "The behaviour and physiology of migrating Atlantic salmon" In: H Ueda and K Tsukamoto (eds),Physiology and Ecology of Fish Migration, CRC Press, pp. 28–55. ISBN 9781466595132.

- Ueda, Hiroshi (2013) "Physiology of imprinting and homing migration in Pacific salmon" In: H Ueda and K Tsukamoto (eds),Physiology and Ecology of Fish Migration, CRC Press, pp. 1–27. ISBN 9781466595132.

- Walker MM, Diebel CE, Haugh CV, Pankhurst PM, Montgomery JC, Green CR (1997). "Structure and function of the vertebrate magnetic sense". Nature. 390 (6658): 371–6. Bibcode:1997Natur.390..371W. doi:10.1038/37057. PMID 20358649.

- Wired. Hacking Salmon’s Mental Compass to Save Endangered Fish 2 December 2008.

- Nitrogen

- Cederholm CJ, Kunze MD, Murota T, Sibatani T (1999). "Pacific salmon carcasses: essential contributions of nutrients and energy for aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems" (PDF). Fisheries. 24 (10): 6–15. doi:10.1577/1548-8446(1999)024<0006:psc>2.0.co;2.

- Gresh T, Lichatowich J, Schoonmaker P (2000). "Salmon Decline Creates Nutrient Deficit in Northwest Streams". Fisheries. 15 (1): 15–21. doi:10.1577/1548-8446(2000)025<0015:AEOHAC>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09.

- Hocking MD, Reynolds JD (2011). "Impacts of salmon on riparian plant diversity" (PDF). Science. 331 (6024): 1609–1612. Bibcode:2011Sci...331.1609H. doi:10.1126/science.1201079. PMID 21442794.

- Naiman RJ, Bilby RE, Schindler DE, Helfield JM (2002). "Pacific salmon, nutrients, and the dynamics of freshwater and riparian ecosystems" (PDF). Ecosystems. 5 (4): 399–417. doi:10.1007/s10021-001-0083-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-24.

- Ruckelshaus MH, Levin P, Johnson JB, Kareiva PM (2002). "The Pacific salmon wars: what science brings to the challenge of recovering species" (PDF). Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 33: 665–706. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.150504.

- Resilience

- Bottom DL, Jones KK, Simenstad CA, Smith CL (2009). "Reconnecting social and ecological resilience in salmon ecosystems" (PDF). Ecology and Society. 14 (1): 5. doi:10.5751/es-02734-140105.

- Bottom DL, Jones KK, Simenstad CA and Smith CL (Eds.) (2010) Pathways to Resilient Salmon Ecosystems Ecology and Society, Special Feature.

External links

- Putting a Price on Salmon True Slant, 9 July 2009.

- Fish passage at dams Northwest Power and Conservation Council. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- Mystery Disease Found in Pacific Salmon Wired, 13 January 2011.

- Pacific Salmon: Anadromous Lifestyles US National Park Service.

- Study takes long-term, diversified view of salmon issues Mount Shasta News, 30 September 2009.