Magnetite

Magnetite is a rock mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe3O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself.[5][6] It is the most magnetic of all the naturally occurring minerals on Earth.[5][7] Naturally magnetized pieces of magnetite, called lodestone, will attract small pieces of iron, which is how ancient peoples first discovered the property of magnetism. Today it is mined as iron ore.

| Magnetite | |

|---|---|

Magnetite from Bolivia | |

| General | |

| Category |

|

| Formula (repeating unit) | iron(II,III) oxide, Fe2+Fe3+2O4 |

| Strunz classification | 4.BB.05 |

| Crystal system | Isometric |

| Crystal class | Hexoctahedral (m3m) H-M symbol: (4/m 3 2/m) |

| Space group | Fd3m |

| Unit cell | a = 8.397 Å; Z = 8 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Black, gray with brownish tint in reflected sun |

| Crystal habit | Octahedral, fine granular to massive |

| Twinning | On {Ill} as both twin and composition plane, the spinel law, as contact twins |

| Cleavage | Indistinct, parting on {Ill}, very good |

| Fracture | Uneven |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 5.5–6.5 |

| Luster | Metallic |

| Streak | Black |

| Diaphaneity | Opaque |

| Specific gravity | 5.17–5.18 |

| Solubility | Dissolves slowly in hydrochloric acid |

| References | [1][2][3][4] |

| Major varieties | |

| Lodestone | Magnetic with definite north and south poles |

Small grains of magnetite occur in almost all igneous and metamorphic rocks. Magnetite is black or brownish-black with a metallic luster, has a Mohs hardness of 5–6 and leaves a black streak.[5]

The chemical IUPAC name is iron(II,III) oxide and the common chemical name is ferrous-ferric oxide.

Properties

In addition to igneous rocks, magnetite also occurs in sedimentary rocks, including banded iron formations and in lake and marine sediments as both detrital grains and as magnetofossils. Magnetite nanoparticles are also thought to form in soils, where they probably oxidize rapidly to maghemite.[8]

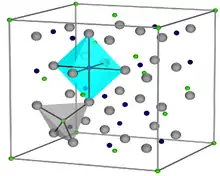

Crystal structure

The chemical composition of magnetite is Fe2+Fe23+O42−. The main details of its structure were established in 1915. It was one of the first crystal structures to be obtained using X-ray diffraction. The structure is inverse spinel, with O2− ions forming a face-centered cubic lattice and iron cations occupying interstitial sites. Half of the Fe3+ cations occupy tetrahedral sites while the other half, along with Fe2+ cations, occupy octahedral sites. The unit cell consists of 32 O2− ions and unit cell length is a = 0.839 nm.[9][10]

Magnetite contains both ferrous and ferric iron, requiring environments containing intermediate levels of oxygen availability to form.[11]

Magnetite differs from most other iron oxides in that it contains both divalent and trivalent iron.[9]

As a member of the spinel group, magnetite can form solid solutions with similarly structured minerals, including ulvospinel (Fe2TiO4), hercynite (FeAl2O4) and chromite (FeCr2O4).

Titanomagnetite, also known as titaniferous magnetite, is a solid solution between magnetite and ulvospinel that crystallizes in many mafic igneous rocks. Titanomagnetite may undergo oxyexsolution during cooling, resulting in ingrowths of magnetite and ilmenite.

Crystal morphology and size

Natural and synthetic magnetite occurs most commonly as octahedral crystals bounded by {111} planes and as rhombic-dodecahedra.[9] Twinning occurs on the {111} plane.[2]

Hydrothermal synthesis usually produce single octahedral crystals which can be as large as 10mm across.[9] In the presence of mineralizers such as 0.1 M HI or 2 M NH4Cl and at 0.207 MPa at 416–800 °C, magnetite grew as crystals whose shapes were a combination of rhombic-dodechahedra forms.[9] The crystals were more rounded than usual. The appearance of higher forms was considered as a result from a decrease in the surface energies caused by the lower surface to volume ratio in the rounded crystals.[9]

Reactions

Magnetite has been important in understanding the conditions under which rocks form. Magnetite reacts with oxygen to produce hematite, and the mineral pair forms a buffer that can control oxygen fugacity. Commonly, igneous rocks contain solid solutions of both titanomagnetite and hemoilmenite or titanohematite. Compositions of the mineral pairs are used to calculate how oxidizing was the magma (i.e., the oxygen fugacity of the magma): a range of oxidizing conditions are found in magmas and the oxidation state helps to determine how the magmas might evolve by fractional crystallization. Magnetite also is produced from peridotites and dunites by serpentinization.

Magnetic properties

Lodestones were used as an early form of magnetic compass. Magnetite typically carries the dominant magnetic signature in rocks, and so it has been a critical tool in paleomagnetism, a science important in understanding plate tectonics and as historic data for magnetohydrodynamics and other scientific fields.

The relationships between magnetite and other iron oxide minerals such as ilmenite, hematite, and ulvospinel have been much studied; the reactions between these minerals and oxygen influence how and when magnetite preserves a record of the Earth's magnetic field.

At low temperatures, magnetite undergoes a crystal structure phase transition from a monoclinic structure to a cubic structure known as the Verwey transition. Optical studies show that this metal to insulator transition is sharp and occurs around 120 K.[12] The Verwey transition is dependent on grain size, domain state, pressure,[13] and the iron-oxygen stoichiometry.[14] An isotropic point also occurs near the Verwey transition around 130 K, at which point the sign of the magnetocrystalline anisotropy constant changes from positive to negative.[15] The Curie temperature of magnetite is 858 K (585 °C; 1,085 °F).

If magnetite is in a large enough quantity it can be found in aeromagnetic surveys using a magnetometer which measures magnetic intensities.[16]

Distribution of deposits

Magnetite is sometimes found in large quantities in beach sand. Such black sands (mineral sands or iron sands) are found in various places, such as Lung Kwu Tan of Hong Kong; California, United States; and the west coast of the North Island of New Zealand.[17] The magnetite, eroded from rocks, is carried to the beach by rivers and concentrated by wave action and currents. Huge deposits have been found in banded iron formations. These sedimentary rocks have been used to infer changes in the oxygen content of the atmosphere of the Earth.[18]

Large deposits of magnetite are also found in the Atacama region of Chile; the Valentines region of Uruguay; Kiruna, Sweden; the Pilbara, Midwest and Northern Goldfields regions in Western Australia; the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia; the Tallawang Region of New South Wales; and in the Adirondack region of New York in the United States. Kediet ej Jill, the highest mountain of Mauritania, is made entirely of the mineral. Deposits are also found in Norway, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, South Africa, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Hong Kong, and in Oregon, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, West Virginia, Virginia, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado in the United States. In 2005, an exploration company, Cardero Resources, discovered a vast deposit of magnetite-bearing sand dunes in Peru. The dune field covers 250 square kilometers (100 sq mi), with the highest dune at over 2,000 meters (6,560 ft) above the desert floor. The sand contains 10% magnetite.[19]

In large enough quantities magnetite can affect compass navigation. In Tasmania there are many areas with highly magnetized rocks that can greatly influence compasses. Extra steps and repeated observations are required when using a compass in Tasmania to keep navigation problems to the minimum.[20]

Magnetite crystals with a cubic habit have been found in just one location: Balmat, St. Lawrence County, New York.[21]

Magnetite can also be found in fossils due to biomineralization and are referred to as magnetofossils.[22] There are also instances of magnetite with origins in space coming from meteorites.[23]

Biological occurrences

Biomagnetism is usually related to the presence of biogenic crystals of magnetite, which occur widely in organisms.[24] These organisms range from bacteria (e.g., Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum) to animals, including humans, where magnetite crystals (and other magnetically sensitive compounds) are found in different organs, depending on the species.[25][26] Biomagnetites account for the effects of weak magnetic fields on biological systems.[27] There is also a chemical basis for cellular sensitivity to electric and magnetic fields (galvanotaxis).[28]

Pure magnetite particles are biomineralized in magnetosomes, which are produced by several species of magnetotactic bacteria. Magnetosomes consist of long chains of oriented magnetite particle that are used by bacteria for navigation. After the death of these bacteria, the magnetite particles in magnetosomes may be preserved in sediments as magnetofossils. Some types of anaerobic bacteria that are not magnetotactic can also create magnetite in oxygen free sediments by reducing amorphic ferric oxide to magnetite.[29]

Several species of birds are known to incorporate magnetite crystals in the upper beak for magnetoreception,[30] which (in conjunction with cryptochromes in the retina) gives them the ability to sense the direction, polarity, and magnitude of the ambient magnetic field.[25]

Chitons, a type of mollusk, have a tongue-like structure known as a radula, covered with magnetite-coated teeth, or denticles.[32] The hardness of the magnetite helps in breaking down food, and its magnetic properties may additionally aid in navigation. Biological magnetite may store information about the magnetic fields the organism was exposed to, potentially allowing scientists to learn about the migration of the organism or about changes in the Earth's magnetic field over time.[33]

Human brain

Living organisms can produce magnetite.[26] In humans, magnetite can be found in various parts of the brain including the frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes, brainstem, cerebellum and basal ganglia.[26][34] Iron can be found in three forms in the brain – magnetite, hemoglobin (blood) and ferritin (protein), and areas of the brain related to motor function generally contain more iron.[34][35] Magnetite can be found in the hippocampus. The hippocampus is associated with information processing, specifically learning and memory.[34] However, magnetite can have toxic effects due to its charge or magnetic nature and its involvement in oxidative stress or the production of free radicals.[36] Research suggests that beta-amyloid plaques and tau proteins associated with neurodegenerative disease frequently occur after oxidative stress and the build-up of iron.[34]

Some researchers also suggest that humans possess a magnetic sense,[37] proposing that this could allow certain people to use magnetoreception for navigation.[38] The role of magnetite in the brain is still not well understood, and there has been a general lag in applying more modern, interdisciplinary techniques to the study of biomagnetism.[39]

Electron microscope scans of human brain-tissue samples are able to differentiate between magnetite produced by the body's own cells and magnetite absorbed from airborne pollution, the natural forms being jagged and crystalline, while magnetite pollution occurs as rounded nanoparticles. Potentially a human health hazard, airborne magnetite is a result of pollution (specifically combustion). These nanoparticles can travel to the brain via the olfactory nerve, increasing the concentration of magnetite in the brain.[34][36] In some brain samples, the nanoparticle pollution outnumbers the natural particles by as much as 100:1, and such pollution-borne magnetite particles may be linked to abnormal neural deterioration. In one study, the characteristic nanoparticles were found in the brains of 37 people: 29 of these, aged 3 to 85, had lived and died in Mexico City, a significant air pollution hotspot. A further eight, aged 62 to 92, came from Manchester, and some had died with varying severities of neurodegenerative diseases.[40] According to researchers led by Prof. Barbara Maher at Lancaster University and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, such particles could conceivably contribute to diseases like Alzheimer's disease. Though a causal link has not been established, laboratory studies suggest that iron oxides like magnetite are a component of protein plaques in the brain, linked to Alzheimer's disease.[41]

Increased iron levels, specifically magnetic iron, have been found in portions of the brain in Alzheimer's patients.[42] Monitoring changes in iron concentrations may make it possible to detect the loss of neurons and the development of neurodegenerative diseases prior to the onset of symptoms[35][42] due to the relationship between magnetite and ferritin.[34] In tissue, magnetite and ferritin can produce small magnetic fields which will interact with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) creating contrast.[42] Huntington patients have not shown increased magnetite levels; however, high levels have been found in study mice.[34]

Applications

Due to its high iron content, magnetite has long been a major iron ore.[43] It is reduced in blast furnaces to pig iron or sponge iron for conversion to steel.

Magnetic recording

Audio recording using magnetic acetate tape was developed in the 1930s. The German magnetophon utilized magnetite powder as the recording medium.[44] Following World War II, 3M Company continued work on the German design. In 1946, the 3M researchers found they could improve the magnetite-based tape, which utilized powders of cubic crystals, by replacing the magnetite with needle-shaped particles of gamma ferric oxide (γ-Fe2O3).[44]

Catalysis

Approximately 2–3% of the world's energy budget is allocated to the Haber Process for nitrogen fixation, which relies on magnetite-derived catalysts. The industrial catalyst is obtained from finely ground iron powder, which is usually obtained by reduction of high-purity magnetite. The pulverized iron metal is burnt (oxidized) to give magnetite or wüstite of a defined particle size. The magnetite (or wüstite) particles are then partially reduced, removing some of the oxygen in the process. The resulting catalyst particles consist of a core of magnetite, encased in a shell of wüstite, which in turn is surrounded by an outer shell of iron metal. The catalyst maintains most of its bulk volume during the reduction, resulting in a highly porous high-surface-area material, which enhances its effectiveness as a catalyst.[45][46]

Magnetite nanoparticles

Magnetite micro- and nanoparticles are used in a variety of applications, from biomedical to environmental. One use is in water purification: in high gradient magnetic separation, magnetite nanoparticles introduced into contaminated water will bind to the suspended particles (solids, bacteria, or plankton, for example) and settle to the bottom of the fluid, allowing the contaminants to be removed and the magnetite particles to be recycled and reused.[47] This method works with radioactive and carcinogenic particles as well, making it an important cleanup tool in the case of heavy metals introduced into water systems.[48] These heavy metals can enter watersheds due to a variety of industrial processes that produce them, which are in use across the country. Being able to remove contaminants from potential drinking water for citizens is an important application, as it greatly reduces the health risks associated with drinking contaminated water.

Another application of magnetic nanoparticles is in the creation of ferrofluids. These are used in several ways, in addition to being fun to play with. Ferrofluids can be used for targeted drug delivery in the human body.[47] The magnetization of the particles bound with drug molecules allows “magnetic dragging” of the solution to the desired area of the body. This would allow the treatment of only a small area of the body, rather than the body as a whole, and could be highly useful in cancer treatment, among other things. Ferrofluids are also used in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology.[49]

Coal mining industry

For the separation of coal from waste, dense medium baths were used. This technique employed the difference in densities between coal (1.3–1.4 tonnes per m³) and shales (2.2–2.4 tonnes per m³). In a medium with intermediate density (water with magnetite), stones sank and coal floated.[50]

Gallery of magnetite mineral specimens

Octahedral crystals of magnetite up to 1.8 cm across, on cream colored feldspar crystals, locality: Cerro Huañaquino, Potosí Department, Bolivia

Octahedral crystals of magnetite up to 1.8 cm across, on cream colored feldspar crystals, locality: Cerro Huañaquino, Potosí Department, Bolivia Magnetite with super-sharp crystals, with epitaxial elevations on their faces

Magnetite with super-sharp crystals, with epitaxial elevations on their faces Alpine-quality magnetite in contrasting chalcopyrite matrix

Alpine-quality magnetite in contrasting chalcopyrite matrix Magnetite with a rare cubic habit from St. Lawrence County, New York.

Magnetite with a rare cubic habit from St. Lawrence County, New York.

See also

- Bluing (steel), a process in which steel is partially protected against rust by a layer of magnetite

- Buena Vista Iron Ore District

- Corrosion product

- Ferrite

- Greigite

- Maghemite

- Magnesia (in natural mixtures with magnetite)

- Magnetotactic bacteria

- Mill scale

- Mineral redox buffer

- Magnes the shepherd

References

- Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W. "Magnetite" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Chantilly, VA: Mineralogical Society of America. p. 333. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- "Magnetite". mindat.org and the Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- Barthelmy, Dave. "Magnetite Mineral Data". Mineralogy Database. webmineral.com. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (20th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-80580-9.

- Hurlbut, Cornelius Searle; W. Edwin Sharp; Edward Salisbury Dana (1998). Dana's minerals and how to study them. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 96. ISBN 978-0-471-15677-2.

- Wasilewski, Peter; Günther Kletetschka (1999). "Lodestone: Nature's only permanent magnet - What it is and how it gets charged". Geophysical Research Letters. 26 (15): 2275–78. Bibcode:1999GeoRL..26.2275W. doi:10.1029/1999GL900496.

- Harrison, R. J.; Dunin-Borkowski, RE; Putnis, A (2002). "Direct imaging of nanoscale magnetic interactions in minerals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (26): 16556–16561. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9916556H. doi:10.1073/pnas.262514499. PMC 139182. PMID 12482930.

- Maher, B. A.; Taylor, R. M. (1988). "Formation of ultrafine-grained magnetite in soils". Nature. 336 (6197): 368–370. Bibcode:1988Natur.336..368M. doi:10.1038/336368a0. S2CID 4338921.

- Cornell; Schwertmann (1996). The Iron Oxides. New York: VCH. pp. 28–30. ISBN 978-3-527-28576-1.

- an alternative visualisation of the crystal structure of Magnetite using JSMol is found here.

- Kesler, Stephen E.; Simon, Adam F. (2015). Mineral resources, economics and the environment (2nd ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107074910. OCLC 907621860.

- Gasparov, L. V.; et al. (2000). "Infrared and Raman studies of the Verwey transition in magnetite". Physical Review B. 62 (12): 7939. arXiv:cond-mat/9905278. Bibcode:2000PhRvB..62.7939G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.242.6889. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.62.7939. S2CID 39065289.

- Gasparov, L. V.; et al. (2005). "Magnetite: Raman study of the high-pressure and low-temperature effects". Journal of Applied Physics. 97 (10): 10A922. arXiv:0907.2456. Bibcode:2005JAP....97jA922G. doi:10.1063/1.1854476. S2CID 55568498. 10A922.

- Aragón, Ricardo (1985). "Influence of nonstoichiometry on the Verwey transition". Phys. Rev. B. 31 (1): 430–436. Bibcode:1985PhRvB..31..430A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.31.430. PMID 9935445.

- Gubbins, D.; Herrero-Bervera, E., eds. (2007). Encyclopedia of geomagnetism and paleomagnetism. Springer Science & Business Media.

- "Magnetic Surveys". Minerals Downunder. Australian Mines Atlas. 2014-05-15. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- Templeton, Fleur. "1. Iron – an abundant resource - Iron and steel". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Klein, C. (1 October 2005). "Some Precambrian banded iron-formations (BIFs) from around the world: Their age, geologic setting, mineralogy, metamorphism, geochemistry, and origins". American Mineralogist. 90 (10): 1473–1499. Bibcode:2005AmMin..90.1473K. doi:10.2138/am.2005.1871.

- Moriarty, Bob (5 July 2005). "Ferrous Nonsnotus". 321gold. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- Leaman, David. "Magnetic Rocks - Their Effect on Compass Use and Navigation in Tasmania" (PDF).

- "The mineral Magnetite". Minerals.net.

- Chang, S. B. R.; Kirschvink, J. L. (May 1989). "Magnetofossils, the Magnetization of Sediments, and the Evolution of Magnetite Biomineralization" (PDF). Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 17 (1): 169–195. Bibcode:1989AREPS..17..169C. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.17.050189.001125. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- Barber, D. J.; Scott, E. R. D. (14 May 2002). "Origin of supposedly biogenic magnetite in the Martian meteorite Allan Hills 84001". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (10): 6556–6561. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.6556B. doi:10.1073/pnas.102045799. PMC 124441. PMID 12011420.

- Kirschvink, J L; Walker, M M; Diebel, C E (2001). "Magnetite-based magnetoreception". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 11 (4): 462–7. doi:10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00235-x. PMID 11502393. S2CID 16073105.

- Wiltschko, Roswitha; Wiltschko, Wolfgang (2014). "Sensing magnetic directions in birds: radical pair processes involving cryptochrome". Biosensors. 4 (3): 221–42. doi:10.3390/bios4030221. PMC 4264356. PMID 25587420. Lay summary.

Birds can use the geomagnetic field for compass orientation. Behavioral experiments, mostly with migrating passerines, revealed three characteristics of the avian magnetic compass: (1) it works spontaneously only in a narrow functional window around the intensity of the ambient magnetic field, but can adapt to other intensities, (2) it is an "inclination compass", not based on the polarity of the magnetic field, but the axial course of the field lines, and (3) it requires short-wavelength light from UV to 565 nm Green.

- Kirschvink, Joseph; et al. (1992). "Magnetite biomineralization in the human brain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 89 (16): 7683–7687. Bibcode:1992PNAS...89.7683K. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.16.7683. PMC 49775. PMID 1502184. Lay summary.

Using an ultrasensitive superconducting magnetometer in a clean-lab environment, we have detected the presence of ferromagnetic material in a variety of tissues from the human brain.

- Kirschvink, J L; Kobayashi-Kirschvink, A; Diaz-Ricci, J C; Kirschvink, S J (1992). "Magnetite in human tissues: a mechanism for the biological effects of weak ELF magnetic fields". Bioelectromagnetics. Suppl 1: 101–13. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.326.4179. doi:10.1002/bem.2250130710. PMID 1285705. Lay summary.

A simple calculation shows that magnetosomes moving in response to earth-strength ELF fields are capable of opening trans-membrane ion channels, in a fashion similar to those predicted by ionic resonance models. Hence, the presence of trace levels of biogenic magnetite in virtually all human tissues examined suggests that similar biophysical processes may explain a variety of weak field ELF bioeffects.

- Nakajima, Ken-ichi; Zhu, Kan; Sun, Yao-Hui; Hegyi, Bence; Zeng, Qunli; Murphy, Christopher J; Small, J Victor; Chen-Izu, Ye; Izumiya, Yoshihiro; Penninger, Josef M; Zhao, Min (2015). "KCNJ15/Kir4.2 couples with polyamines to sense weak extracellular electric fields in galvanotaxis". Nature Communications. 6: 8532. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8532N. doi:10.1038/ncomms9532. PMC 4603535. PMID 26449415. Lay summary.

Taken together these data suggest a previously unknown two-molecule sensing mechanism in which KCNJ15/Kir4.2 couples with polyamines in sensing weak electric fields.

- Lovley, Derek; Stolz, John; Nord, Gordon; Phillips, Elizabeth. "Anaerobic production of magnetite by a dissimilatory iron-reducing microorganism" (PDF). geobacter.org. US Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 22092, USA Department of Biochemistry, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts 01003, USA. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- Kishkinev, D A; Chernetsov, N S (2014). "[Magnetoreception systems in birds: a review of current research]". Zhurnal Obshcheĭ Biologii. 75 (2): 104–23. PMID 25490840. Lay summary.

There are good reasons to believe that this visual magnetoreceptor processes compass magnetic information which is necessary for migratory orientation.

- Lowenstam, H.A. (1967). "Lepidocrocite, an apatite mineral, and magnetic in teeth of chitons (Polyplacophora)". Science. 156 (3780): 1373–1375. Bibcode:1967Sci...156.1373L. doi:10.1126/science.156.3780.1373. PMID 5610118. S2CID 40567757.

X-ray diffraction patterns show that the mature denticles of three extant chiton species are composed of the mineral lepidocrocite and an apatite mineral, probably francolite, in addition to magnetite.

- Bókkon, Istvan; Salari, Vahid (2010). "Information storing by biomagnetites". Journal of Biological Physics. 36 (1): 109–20. arXiv:1012.3368. Bibcode:2010arXiv1012.3368B. doi:10.1007/s10867-009-9173-9. PMC 2791810. PMID 19728122.

- Magnetite Nano-Particles in Information Processing: From the Bacteria to the Human Brain Neocortex - ISBN 9781-61761-839-0

- Zecca, Luigi; Youdim, Moussa B. H.; Riederer, Peter; Connor, James R.; Crichton, Robert R. (2004). "Iron, brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 5 (11): 863–873. doi:10.1038/nrn1537. PMID 15496864. S2CID 205500060.

- Barbara A. Maher; Imad A. M. Ahmed; Vassil Karloukovski; Donald A. MacLaren; Penelope G. Foulds; David Allsop; David M. A. Mann; Ricardo Torres-Jardón; Lilian Calderon-Garciduenas (2016). "Magnetite pollution nanoparticles in the human brain" (PDF). PNAS. 113 (39): 10797–10801. Bibcode:2016PNAS..11310797M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1605941113. PMC 5047173. PMID 27601646.

- Eric Hand (June 23, 2016). "Maverick scientist thinks he has discovered a magnetic sixth sense in humans". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aaf5803.

- Baker, R R (1988). "Human magnetoreception for navigation". Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 257: 63–80. PMID 3344279.

- Kirschvink, Joseph L; Winklhofer, Michael; Walker, Michael M (2010). "Biophysics of magnetic orientation: strengthening the interface between theory and experimental design". Journal of the Royal Society, Interface. 7 Suppl 2: S179–91. doi:10.1098/rsif.2009.0491.focus. PMC 2843999. PMID 20071390.

- BBC Environment:Pollution particles 'get into brain'

- Wilson, Clare (5 September 2016). "Air pollution is sending tiny magnetic particles into your brain". New Scientist. 231 (3090). Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- Qin, Y., Zhu, W., Zhan, C. et al. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. [Med. Sci.] (2011) 31: 578.

- Franz Oeters et al"Iron" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2006, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a14_461.pub2

- Schoenherr, Steven (2002). "The History of Magnetic Recording". Audio Engineering Society.

- Jozwiak, W. K.; Kaczmarek, E.; et al. (2007). "Reduction behavior of iron oxides in hydrogen and carbon monoxide atmospheres". Applied Catalysis A: General. 326: 17–27. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2007.03.021.

- Appl, Max (2006). "Ammonia". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a02_143.pub2.

- Blaney, Lee (2007). "Magnetite (Fe3O4): Properties, Synthesis, and Applications". The Lehigh Review. 15 (5).

- Rajput, Shalini; Pittman, Charles U.; Mohan, Dinesh (2016). "Magnetic magnetite (Fe 3 O 4 ) nanoparticle synthesis and applications for lead (Pb 2+ ) and chromium (Cr 6+ ) removal from water". Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 468: 334–346. Bibcode:2016JCIS..468..334R. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2015.12.008. PMID 26859095.

- Stephen, Zachary R.; Kievit, Forrest M.; Zhang, Miqin (2011). "Magnetite nanoparticles for medical MR imaging". Materials Today. 14 (7–8): 330–338. doi:10.1016/s1369-7021(11)70163-8. PMC 3290401. PMID 22389583.

- Nyssen, J; Diependaele, S; Goossens, R (2012). "Belgium's burning coal tips - coupling thermographic ASTER imagery with topography to map debris slide susceptibility". Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie. 56 (1): 23–52. Bibcode:2012ZGm....56...23N. doi:10.1127/0372-8854/2011/0061.

Further reading

- Lowenstam, Heinz A.; Weiner, Stephen (1989). On Biomineralization. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504977-0.

- Chang, Shih-Bin Robin; Kirschvink, Joseph Lynn (1989). "Magnetofossils, the Magnetization of Sediments, and the Evolution of Magnetite Biomineralization" (PDF). Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 17: 169–195. Bibcode:1989AREPS..17..169C. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.17.050189.001125.

External links

- Mineral galleries

- Bio-magnetics

- Magnetite mining in New Zealand Accessed 25-Mar-09