Seabees in World War II

When World War II broke out the United States Naval Construction Battalions (Seabees) did not exist. The logistics of a two theater war were daunting to conceive. Rear Admiral Moreell completely understood the issues. What needed to be done was build staging bases to take the war to the enemy, across both oceans, and create the construction force to do the work. Naval Construction Battalions were first conceived at Bureau of Yards and Docks (BuDocks) in the 1930s. The onset of hostilities clarified to Radm. Moreell the need for developing advance bases to project American power. The solution: tap the vast pool of skilled labor in the U.S. Put it in uniform to build anything, anywhere under any conditions and get the Marine Corps to train it. The first volunteers came skilled. To obtain these tradesmen, military age was waived to age 50. It was later found that several past 60 had managed to get in. Men were given advanced rank/pay based upon experience making the Seabees the highest paid group in the U.S. military.[1] The first 60 battalions had an average age of 37.

| Naval Construction Battalions | |

|---|---|

The Seabee logo | |

| Founded | 28 December 1941 (requested), 5 March 1942 (authorized) |

| Role | Militarized construction |

| Size | 258,000 |

| Nickname(s) | Seabees |

| Motto(s) | "Can Do" |

| Colors | |

| Mascot(s) | Bumblebee |

| Engagements | Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Cape Gloucester, Los Negros, Kwajalein, Saipan, Tinian, Guam, Peleliu, Tarawa, Philippines, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, Normandy landing, Sicily, Anzio, North Africa |

| Website | https://www.public.navy.mil/seabee/Pages/default.aspx |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Admiral Ben Moreell |

"December 1942 saw voluntary Seabee enlistments cease per presidential order. For the next year the Selective Service System provided younger unskilled recruits."[2] The Seabee solution were Construction Training Centers with courses in over 60 trades. In the field seabees became renowned for the arts of obtaining materials by unofficial and unorthodox means,[note 1][3] and souvenir making. Bulldozers, steel pontoons, steel mat, and corrugated steel, combined with "ingenuity and elbow grease became synonymous with Seabees[4] Nearly 11,400 became officers in the Civil Engineer Corps of which nearly 8,000 served with CBs. During the war the Naval Construction Force (NCF) was simultaneously spread across multiple projects worldwide. On 13 February 1945 Chief of Naval Operations, Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, made the NCF a permanent Naval element.[5] Before that happened Seabees had volunteered for many tasks outside the NCF: Naval Combat Demolition Units, UDTs, Marine Corps Engineers/Pioneers and the top secret Chemical Warfare Service Flame tank Group.

Pre-war naval construction development

In the late 1930s the US saw the need to prepare militarily. Congress authorized the expansion of naval Shore Activities in the Caribbean and by 1939 in the Central Pacific. "Following standard peacetime guidelines the Navy awarded contracts to civilian constructions firms. These contractors employed native civilian populations as well as U.S citizens and were answerable to naval officers in charge of construction. By 1941 large bases were being built on Guam, Midway, Wake, Pearl Harbor, Iceland, Newfoundland, Bermuda, and Trinidad to name a few."[6] International law, dictated civilians not to resist enemy military attacks. Resistance meant they could be summarily executed as guerrillas.[7] Wake turned out to be an case in point for Americans.

World War II

.jpg.webp)

The need for a militarized construction force became evident after the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor. On December 28 Radm. Moreell requested authority to create Naval Construction Battalions. The Bureau of Navigation gave authorization on 5 January 1942.[8] Three Battalions were officially authorized on 5 March 1942. Enlistment was voluntary until December when the Selective Service System became responsible for recruitment. Seabee Training Centers were named for former heads of the Civil Engineer Corps: Radm. Mordecai T. Endicott, Radm. Harry H. Rousseau, Radm. Richard C. Hollyday, Radm. Charles W. Park.[9] Camp Peary was named for RADM. Robert Peary. The Seabees also named a Center for the first CEC killed in action, Lt. Irwin W. Lee and Lt. (jg) George W. Stephenson of the 24th CB.[10]

A pressing issue for the BuDocks was CB command.[8] Navy regulations stated that command of naval personnel was limited to line officers of the fleet. BuDocks deemed it essential that CBs be commanded by CEC officers trained in construction.[8] The Bureau of Naval Personnel strongly objected to this violation of Naval tradition.[8] Radm. Moreell took the issue directly to the Secretary of the Navy.[8] On March 19 the Secretary gave the CEC complete command of all those assigned to naval construction units.[8] With CBs authorized and the command question settled, BuDocks then had to deal with recruitment and training. Following that, was deciding the military organization structure and organizing the logistical support necessary to make everything work. That all happened quickly. Due to the exigencies of war there was a great deal of "improvisation", a quality that became synonymous with Seabees in general.[11]

"At Naval Construction Training Centers (NCTC) and Advanced Base Depots (ABD) on both coasts, men learned: trade skills, military discipline, and advanced combat training. Although technically designated "support", Seabees frequently found themselves under fire with the Marines. After completing boot training at Camp Allen VA. and later Camp Peary VA, the men were formed into CBs or other smaller CB units. The first five battalions were deployed immediately upon completion of training due to the backlog of projects. Battalions that followed were sent to an ABDs at either Davisville, Rhode Island, or Port Hueneme, California to be staged prior to shipping out. Basic military training was done by the Navy while the Marine Corps provided advanced military training at Camp Peary, Camp Lejeune or Camp Pendelton. About 175,000 Seabees were staged out of Port Hueneme during the war. Units that had seen extended service in the Pacific were returned to the R&R Center at Camp Parks, Shoemaker, CA. There units were reorganized, re-deployed or decommissioned. Men were given 30-day leaves and later, those eligible were discharged. The same was done at the Davisville, Rhode Island, for the east coast."[2]

From California, battalions attached to III Amphibious Corps or V Amphibious Corps, were staged to the Moanalua Ridge Seabee encampment in the Hawaiian Territory. It covered 120 acres and had 20 self-contained areas for CB units.[12] Within each area were 6 two-story barracks served by a 1,200 man galley and messhall plus 8 standard quonsets for offices, dispensary, officers quarters and a single large quonset for the ships store.[12] The entire facility had water, sewer, electricity, pavements, armory and a large outdoor theater.[12] A second CB encampment of 4 additional 1000 man Quonsit areas was built on Iroquois Point.[13] Battalions attached to the 7th Amphibious Fleet were staged at Camp Seabee next to the ABCD in Brisbane Australia.

The Atlantic theater

"When the war became a two-ocean war, the Panama Canal became geographically strategic. The convergence of shipping lanes necessitated bases to protect its approaches. Agreements in the Caribbean made that possible as did the Lend Lease Agreement. Under the Greenslade Program naval bases in Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Panama Canal Zone were all expanded. In Puerto Rico Naval Station Roosevelt Roads was turned into the "Pearl Harbor of the Caribbean. Construction on existing bases was done primarily by civilian contractors until late 1943 when CBs took over. In the Atlantic, the bases formed a line from Bermuda to Brazil. On the Pacific side of the Americas the U.S had bases from the Honduras to Ecuador.[14] The 80th(colored) CB upgraded Carlson airfield on Trinidad. The 83rd CB cut a highway out of Port of Spain, that required moving one million cubic yards of material."[14] "On the Galapagos Islands, CBD 1012 constructed a seaplane base with tank farm and did the same again at Salinas, Ecuador. Salinas would be the southernmost U.S. base in the Pacific. While not in combat zones these bases were necessary for the overall war effort."[14]

"North Africa was the Seabees' first combat. Landing with the assault in November 1942, they built facilities at Oran, Casablanca, Sifi, and Fedala. Later they would build a string of staging and training areas along the Mediterranean including NAS Port Lyautey, Morocco."[11]

"Once Tunisia was taken the Seabees began a buildup at Bizerte. There they prepped steel pontoon boxes for their first use in combat at Sicily. This Seabee "innovation" was adapted for amphibious warfare. A pontoon box was standardized in size so multiple pontoons could be quickly assembled like to form causeways, piers, or rhinos. As such they could be used to meet the exigencies of amphibious warfare. The beaches of Sicily were considered impossible for an amphibious landing by both the Allies and Axis. The Seabees with their pontoons proved that was not true. The Germans were overwhelmed by the men and material that poured ashore over them.[11]

"Seabee causeways were used again at Salerno and Anzio. The Germans were prepared causing heavy casualties at both. At Anzio Seabees were under continuous fire for a long time. After Southern Italy the Seabees had one last task in the theater, Operation Dragoon."[11]

"Seabee operations in the North Atlantic began early 1942. The first were in Iceland, Newfoundland, and Greenland. These airfields and ports supported Allied convoys. To complete the defensive line these bases made, Seabees were sent to Londonderry, Northern Ireland, Lough Erne, Loch Ryan, and Rosneath, Scotland. Depots, fuel farms, and seaplane bases were constructed to anchor the line. Afterwards the Seabees went South for Operation Overlord preparations. They built invasion bases from Milford Haven to Exeter and prepared for their own multifaceted D-day role."[11]

On D-Day Seabees were the first ashore as Naval Combat Demolition Units (NCDU). Their task was to remove German defensive beach obstructions built to impede amphibious landings.[11] "They came under very heavy fire, but placed and detonated all their charges. The gaps created permitted the assault to hit the beach. To facilitate this Seabees placed pontoon causeways over which the assault could access the gaps."[11] "Seabees also brought their Rhino ferries, a motorized adaptation of their modular pontoon boxes. With them, vast amounts of men and material went ashore. For the American sector Seabees assembled piers, and breakwaters into Mulberry A. It was a temporary port until French ports were liberated. Even after weather disabled the Mulberry, Seabees continued to get thousands of tons supplies and troops ashore."[11]

"The liberation of Cherbourg and Le Havre gave CBs major projects. These were the harbors that would replace Mulberry A. Foreseeing the Allies would want those harbors the Germans had left them in ruins. At Cherbourg the first cargo landed 11 days of the Seabees and within a month it was handling 14 ships simultaneously. Seabees repeated this at Le Havre and again at Brest, Lorient, and St. Nazaire."[11]

"The last Seabee project in Europe was the crossing of the Rhine. The U.S. Army called for Seabees to do the job, but General Patton ordered they wear Army fatigues to do it. They crossed first at Bad Neuenahr near Remagen and the Seabees made the operation work as planned. On 22 March 1945, the Seabees put Gen. George S. Patton and his armor across at Oppenheim, on pontoon ferries. More than 300 craft were involved. One crew even took Prime Minister Churchill across." [11]

"The 69th was the only CB to set foot in Germany. They also were the first CB to deployed by air. They were flown to Bremen in April 1945 tasked to repair damaged buildings and power lines for the U.S. occupation force. Making the port of Bremerhaven operational also fell to them. One detachment was sent to Frankfurt-am-Main to make the U.S. Navy Hq in Germany. By August 1945 the battalion was back in England concluding Atlantic operations."[11]

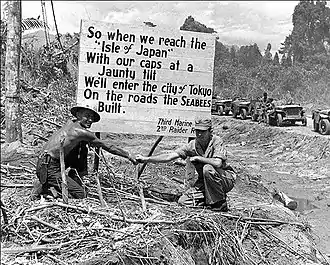

The Pacific theater

"Pacific Seabee deeds were historically unparalleled.[15] The Pacific was where 80% of the NCF literally built the road to V-J-day. It built all the airfields, piers, ammunition bunkers, supply depots, hospitals, fuel tanks, and barracks required to make it happen on 300 plus islands."[11]

"The entire Pacific, including Alaska and the Aleutians were Japanese targets. Japanese operations of 1942, took the islands of Attu and Kiska. Seabees sent to the North were there to work on stalling what appeared at the time to be a major Japanese offensive. By late June 1942 bases were being built on Adak and Amchitka which served as deterrents for the remainder of the war."[11]

"The first CB projects were on Bora Bora where the 1st CB Detachment arrived February 1942. The det took the name "Bobcats" from the Operation's code name BOBCAT (they deployed before the "Seabee" name was created). The project was a fuel depot on the down under route to Australia. They encountered typical issues of the tropics: incessant rain, 50 types of dysentery, numerous skin problems, and the dreaded elephantiasis. Combined they made conditions miserable, and were harbingers of what was awaiting Seabees else wheres. That det was beset with difficulties, but gained satisfaction when the island's tank farms fueled Task Force 44 for the Battle of the Coral Sea."[11]

"While the Bobcats were in transit to Bora Bora the 2nd and 3rd CB Detachments were formed. The 2nd went to Tongatapu in the Tonga Islands while the 3rd went to Efate in the New Hebrides. Both lay on down under routes too. Bases built on them would support actions in the Coral Sea and the Solomon Islands. Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides became strategic when the Japanese took Guadalcanal and started airfields there. The 3rd CB Det was rushed from Efate to Espiritu Santo to build a countermanding field asap. Within 20 days a 6000ft airstrip was operational.

CB 3 sent a detachment to Bora Bora to augment the Bobcats.[16] In the fall of 1943 the Seabees all received orders to Noumea to join CB 3. Before that happened they were redesignated 3rd Battalion 23rd Marines.[16] The remainder of A Co. CB 3 was transferred to the 22nd as well. Neither the Bobcats nor A Co had not received advanced military training before deploying so the 22nd Marines gave them all an intense field version on Bora Bora. Afterwards the regiment returned to Hawaii for amphibious warfare training.[16] For the Marshalls landings 3rd Battalion was tasked as shore party, engineers and demolitions men.[16] They would see extensive combat at the Battle of Eniwetok. When those operations were over the 22nd Marines were given a Naval Unit Commendation and the Bobcats and A Co 3 CB were released by the Marines.[16]

_at_Noumea%252C_New_Caledonia%252C_10_November_1942%252C_while_the_Big_E_was_undergoing_repairs_after_the_Battle_of_Santa_Cruz.jpg.webp)

On 30 October 1942 the USS Enterprise (CV-6) pulled into Noumea damaged from the Battle of Santa Cruz.[17] She was the only air craft carrier remaining in the Pacific west of Pearl Harbor, but had a bomb go through the flight deck at the bow and just aft of the forward elevator.[17] One near miss was midships below the waterline while another was adjacent the elevator hit.[17] B Co. from CB 3 put a 75-man aboard her to assist effect emergency repairs en route to her next engagement in the Solomons. Underway with the ship ordered to engage the enemy, the Seabees focused on the repairs even into the battle.[17] They had worked round-the-clock under the Enterprise's damage control officer.[18] He wrote that on 11 November: "She made the open sea with her decks... shaking and echoing to air hammers, with welders' arcs sparking... and with her forward elevator still jammed... since the bomb...broke it in half."[19] On 13 November the ship's Captain of notified SOPAC in Noumea that "The emergency repairs accomplished by this skillful, well-trained, and enthusiastically energetic force have placed this vessel in condition for further action against the enemy".[20] Those repairs enabled the Enterprise to engage and sink the Japanese battleship Hiei that day. Over the next three days her planes would be involved in the sinking of 16 and damaging another 8.[17] When it was over and Vice Admiral Bull Halsey knew what those Seabee repairs meant to the outcome. He sent a commendatory letter to the Seabee's OIC, Lt. Quayle: "Your commander wishes to express to you and the men of the Construction Battalion serving under you, his appreciation for the services rendered by you in effecting emergency repairs during action against the enemy. The repairs were completed by these men with speed and efficiency. I hereby commend them for their willingness, zeal, and capability."[21] The Navy learned from this that the fleet could turn to the Seabees for repairs. The 27th CB created its own "Ships Repair Shop" as a courtesy to the fleet. Its divers replaced 160 damaged ship's props. That "Shop" logged major repairs on 145 vessels, including 4 submarines.[22] The 74th had a shop that changed a similar number number of props.[23]

The 6th CB became the first CB to see combat with the 1st Marine Division on Guadalcanal. Their task was keeping Henderson Field operational. The Japanese made this a never-ending job bombing it as fast as the Seabees repaired it. The first Seabee Silver Star was for actions there."[11] "The Marines/Seabees made simultaneous landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi Island. On Tulagi it was to construct the PT base behind the famous sea battles in the "slot""[11] PT Squadron 2 was there and requested Seabee volunteers nightly to fill out its crews.[22] It also would be Hq Motor Torpedo Boat So. Pacific Command MTBSoPac. News worthy to the troops at the time, off Tassafaronga Point on Guadalcanal, Seabees in a Higgins boat ran into the periscope of a sunk Japanese two-man sub 300 yd (270 m) offshore.[24] It was in 20 ft (6.1 m) of water and with improvised diving gear they hooked cables for bulldozers to pull it ashore. With bulldozers straining, eight sticks of dynamite blast it free of the mud suction force and it was beached. It became a "must see" for U.S troops on Guadalcanal.[11]

Like CBs, PTs were new in WWII. The Seabees would build 119 PT bases. The largest would be on Mios Woendi. Many battalions were involved, however, the 113th and 116th Construction Battalions had PT Advance Base construction detachments. The 113th's det was attached to Task Group 70.1[25] through the end of the war. It was a precursor to postwar Seabee teams. Each man was cross-trained in at least three trades with some qualified as corpsmen and divers.[26]

As the war island-hopped the Solomons, the Russells, Rendova, New Georgia, and Bougainville CBs turned all into some kind of advanced base. "Mid-1943 Merauke, New Guinea got an air strip and comm station at Port Moresby. In December Seabees with the 1st Marine Division landed at Cape Gloucester. There, Seabees of the 19th Marines bulldozed trails for armor beyond the front lines so far they had to be told to hold up.[11]

Prior to Cape Gloucester the 1st Marine Division posted for flight qualified volunteers to form an aviation unit to of Piper L4 Grasshoppers.[27] Sixty stepped forward with a dozen having flight time. A Seabee in the 17th Marines, MM2 Chester Perkins, was one.[28] Perkins and the others were put through two months recon and artillery spotting training once the Grasshoppers arrived. He logged over 200 hours dropping flares ammo, medical supplies, observing troop movements, and providing taxi service to officers.[28] For this Maj. Gen. Rupertus, USMC promoted him to Staff sergeant/Petty officer 1st class and Admiral Nimitz wrote him and the other flyers commendations for the Navy Air Medal.[28]

"The Admiralities became key to isolating Rabaul and the neutralization of New Britain. The seizure of Manus Island and Los Negros Island cut supplies from all points north and east. By 1944 Seabees had transformed those islands into the largest Lion and Oak in the Southwest Pacific. The Lion became the main supply and repair depot of the Seventh Fleet. The capture of Emirau completed the encirclement of Rabaul. A strategic two-field Oak, with depots, dry dock, and PT base was constructed there."[11]

"The Central Pacific saw CBs both directly and indirectly involved in combat. Landing in all the assaults, their efforts moved the U.S relentlessly toward the Japanese homeland. Tarawa in the Gilberts was bad, but in fifteen hours Seabees had the airfield operational. They turned Majuro Atoll into one of the fleet's Lions and similarly transformed Kwajalein Atoll into a Oak."[11]

"Seizure of the Marianas turned the Pacific war. Their loss cut the Japanese defense and placed Japan within bomber range. Operation Forager saw Seabees make some of their most significant contributions in the Pacific at Kwajalein, Saipan, Guam, and Tinian. On Siapan and Tinian top secret Seabee work was fielded by the 2nd and 4th Tank Battalions, flamethrowing tanks. Within four days of capture, Seabees had Aslito on Saipan operational. During the battle for Guam, CB Specials did stevedoring while others were Marine combat engineers. When they were done CBs turned Guam into a Lion for the fleet and an Oak for the air corps. The invasion of Tinian was a showcase of Seabee ingenuity and engineering. The CEC engineered detachable ramps mounted on LVT-2s making landings possible where the Japanese thought it was impossible. Before the island was even secure, Seabees were completing an unfinished Japanese airfield."[11]

During 1944 dredging harbors to facilitate movement of men, supplies, and vessels became an unheralded priority. The 301st CB was formed to do the job and given two ex-NCDU and two ex-UDT CEC to help. Between them they had three Silver stars and one Bronze.

"Once the Marianas were taken B-29s needed an emergency field and a forward base for fighter escort. Iwo Jima was chosen for V Amphibious Corps to assault on 19 February 1945. The assault had 4 battalions tasked as shore party: 4th & 5th Pioneers and 31st & 133rd CBs. The 133rd suffered the most casualties in Seabee History tasked to the 23rd Marines D-day-D+18. Only basic road construction was accomplished during the first days. Work on the first airfield began on D+5.[11] On Iwo Jima it got so that the Marines would hold up the assault to wait for one of their Seabee built flamethrowering tanks.

"Island hopping CBs made Hollandia instrumental in the liberation of the Philippines. The 3rd Naval Construction Brigade was part of MacArthur's return to Leyte. Seabee pontoons brought MacArthur's Forces ashore. The 3rd was joined by the 2nd and 7th Naval Construction Brigades. This NCF totaled 37,000 and turned the Philippines into a huge forward base. The 7th Fleet moved Hq there with Seabees building everything needed: fleet anchorages, sub bases, fleet repair facilities, fuel and supply depots, Pt bases and air stations.[11] At Dulag, Leyte Seabee activity became an issue to the Japanese. There, the 61st CB had a air strip detachment assaulted by Japanese paratroopers. The assault lasted 72 hours, costing the Japanese over 350 men.[29] As in the South Pacific, PTs had Seabees augmenting crews on runs along Halmahera in the Lembeh Strait.[30]

"At Okinawa the 24th Army Corps and Third Marine Amphibious Corps landed off Rhinos and causeways of the 130th CB. The 58th, 71st, and 145th CBs were attached to the three Marine Division. The Seabees created an entire Battalion of flamethrowering tanks for the assault. Numerous CBs followed, as Okinawa became the anticipated jumping-off point for invasion of Japan. Nearly 55,000 in four CB brigades were there. By August 1945 everything was prepped for the invasion."[11]

When the USS Indianapolis (CA-35) delivered the atomic bomb to Tinian[31] 6th Brigade Seabees unloaded the components, stored and posted guard.[31] When technicians assembled the weapon Seabees assisted as needed.[31] On 6 August it was loaded into a B29[31] for the bombing of Hiroshima. When the war ended 258,872 officers and enlisted had served in the Seabees. Their authorized allotment of 321,056 was never reached.[32] The war saw over 300 Seabees killed in action while over 500 died on the job site.[33] U.S. Fleet Admiral Halsey: "The Seabees helped crush the Japs in every South Pacific campaign".[34]

Lions, Cubs, Oaks, Acorns advance base units

Advance base construction operations were given a code name as a numbered metaphor for the size/type of base the Seabees were to construct and assigned to it the "unit" charged with development and administration of that base.[35] These were Lion, Cub, Oak and Acorn with a Lion being a large Fleet Base numbered 1–6.[36] Cubs were Secondary Fleet Bases 1/4 the size of a Lion (numbered 1–12 and most often for PT boats)[37] Oak and Acorn were the names given airfields, new or captured enemy fields (primary and secondary in size).[38] Cubs were quickly adopted as the primary type airfield with few Oaks. Of the three base types Lions, Cubs and Acorns, Acorns received priority due to their tactical importance and the speed at which the Seabees could make one operational. The Navy believed the Seabees could produce an operational runway overnight. In the Office of Naval Operations manual for Logistics of Advance Bases it reads " Highly mobile Acorns...can be established by surprise tactics between sunset and sunrise on enemy territory...(are) strategically important... offensive instruments possessing tactical surprise to a highly portentous degree."[39]:Page 88

Camp Bedilion was home to the Acorn Assembly and Training Detachment responsible for training and organizing Acorn units. It shared a common fenceline with Camp Rousseau at Port Hueneme.[40] A Lion, Cub, or Acorn was composed of three components: Base Operation units, Fleet/Aviation repair-maintenance units and Construction Battalion personnel. CBs constructed, repaired or upgraded 111 major airfields with the number of acorn fields not published.[41] When the code was first created the Navy thought it would require two CBs to construct a Lion. By 1944 entire Construction Regiments were being used to build Lions.

Lions, Cubs, Oaks, Acorns USN Administration in WWII:[39] ACORN: acronym for Aviation, Construction, Ordnance, Repair. A CBMU was attached to every ACORN. A single island could have multiple Acorns on it. It was common practice to separate airfields for bombers and fighters. In December 1944 the Navy took over an unused Army Air Corps base at Thermal, CA. making it Naval Air Field Thermal. The Navy made it the pre-embarkation and training center for Acorns, CASUs, and CBMUs.

- Lion 1 Espirtu Santo[42](40th CB)

- Lion 4 Manus

- Lion 6 Guam

- Cub 1 Guadalcanal[43]

- Cub 2 Tulagi

- Cub 9 Guadalcanal

- Cub 12 Emirau

- Acorn 1 Guadalcanal

- Acorn Red 1 Guadalcanal

- Acorn 2 Espirto Santo

- Acorn 3 Banika/south[44]

- Acorn Red 3 Green Island

- Acorn 4 Tulagi[45]

- Acorn 5 Woodlark[46]

- Acorn 7 Emirau

- Acorn 8 Noumea

- Munda Point

- Biak

- Acorn 10 Green Island

- Acorn 11 Nouméa

- Acorn 12 Banika/Sterling Island

- Acorn 13 Espirtu Santo (bomber field 1)

- Acorn 14 Tarawa

- Acorn 15 Green Island[47] (93rd CB)

- Acorn 16 Apamama

- Acorn 17 South Tarawa(Kiribati)[48]

- Acorn 18 Espirto Santo (bomber field 2)

- Acorn 19 Mindoro

- Acorn 22 Eniwetok

- Acorn 21 Roi-Namur

- Acorn 23 Kwajalein (Ebeye)[49]

- Acorn 24 Los Negros

- Acorn 29 Yonabara

- Acorn 30 Jinamoc Tacloban, Leyte[50]

- Acorn 33 Samar[50]

- Acorn 38 Saipan

- Acorn 41 Marpi point, Saipan

- Acorn 44 Okinawa[51]

- Acorn 45 Sangley Point, Cavite[50]

- Acorn 46 Marpi, Saipan

- Acorn 47 Puerto Princesa[50]

- Acorn 50 Kobler, Saipan

- Acorn 51 Cebu/Mactan Island[40]

- Acorn 55 commissioned at the Argus Assembly and Training Unit, Port Hueneme

Espirto Santo war's end

.jpg.webp)

At the end of WWII Espiritu Santo had become the second largest base the U.S. had in the Pacific. To deal with the vast quantities of supplies and equipment staged there the military had to find a solution.[52] It cost too much to send back to the states and would hurt industry by flooding the market with cheap military surplus. Additionally, the Navy was more concerned about discharging men and mothballing ships. The answer was to offer to sell it to the French for 6 cents on the dollar. The French thought they wouldn't offer anything and the U.S would abandon it all.[52] Instead the U.S ordered the Seabees to build a ramp into the sea by Luganville Airfield.[52] There, day after day the surplus went into the water. Seabees wept at what they had to do.[52] Today the site is a tourist attraction called Million Dollar Point. Individual CBs were ordered to do the same across the Pacific with Guam another example.[53]

CB rates

These indicate the construction trade in which a Seabee is skilled. During WWII, the Seabees were the highest-paid group in the U.S. military, due to all the skilled journeymen in their ranks. [54][55] Camp Endicott had roughly 45 vocational schools plus additional specialized classes. These included Air compressors, Arc welding, BAR, Bridge building, Bulldozer, Camouflage, Carpentry, Concrete, Cranes, Dams, Diving, Diesel engines, Distillation and water purification, Dock building, Drafting, Drilling, Dry docks, Dynamite and demolition, Electricity, Electric motors, First aid, Fire fighting, Gasoline Engines, Generators, Grading roads and airfields, Ice makers, Ignition systems, Judo, Huts and tents, Lubrication, Machine gun, Marine engines, Marston Matting, Mosquito control, Photography, Pile driving, Pipe-fitting/plumbing, Pontoons, Power-shovel operation, Pumps, Radio, Refrigeration, Rifle, Riveting, Road building, Road Scrapers, Sheet metal, Soil testing, Steelworking, Storage tanks wood or steel, Tire repair, Tractor operation, Transformers, Vulcanizing, Water front, and Well-drilling.[56]

- BMCB : Boatswains Mate Seabee

- CB : Construction Battalion ( first rate in 1942 for all construction trades)

- CMCBB : Carpenters Mate CB Builder

- CMCBD : Carpenters Mate CB Draftsman

- CMCBE : Carpenters Mate CB Excavation foreman

- CMCBS : Carpenters Mate CB Surveyor

- EMCBC : Electricians Mate CB Communications

- EMCBD : Electricians Mate CB Draftsman

- EMCBG : Electricians Mate CB General

- EMCBL : Electricians Mate CB Line and Station

- GMCB : Gunners Mate CB

- GMCBG : Gunners Mate CB Armorer

- GMCBP : Gunners Mate CB Powder-man

- MMCBE : Machinists Mate CB Equipment Operator

- SFCBB : Ship Fitter CB Blacksmith

- SFCBM : Ship Fitter CB Draftsman

- SFCBP : Ship Fitter CB Pipe-fitter and Plumber

- SFCBR : Ship Fitter CB Rigger

- SFCBS : Ship Fitter CB Steelworker

- SFCBW : Ship Fitter CB Welder

- Diver

The Seabees had a divers school of their own to qualify 2nd class divers. During WWII being a diver was not a "rate", it was a "qualification" that had four grades: Master, 1st Class, Salvage, and 2nd Class.[57] CBs would put men in the water from the tropics to the Arctic circle. In the Aleutians CB 4 had divers doing salvage on the Russian freighter SS Turksib in 42 °F water.[58] In the tropics Seabee divers would be sent close to an enemy airfield to retrieve a Japanese aircraft.[59] At Halavo on Florida Island divers from the 27th CB would recover a Disburser's safe full of money plus change 160 props on vessels of all sizes.[22] The Seabees of the 27th CB alone, logged 2.550 diving hours with 1,345 classified as "extra hazardous".[22] Seabee Underwater Demolition Teams were swimmers during WWII, but postwar transitioned to divers. Another historic note to the Seabees is that they had African American divers in the 34th CB. Those men fabricated their diving gear in the field using Navy Mk-III gas masks as taught at diving school. Twice, while at Milne Bay, the 105th CB sent special diving details on undisclosed missions. At Pearl Harbor Seabee Divers were involved in the salvage of many of the ships hit on 7 December as well as the recovery of bodies for a long time after the attack.[60][61] Divers in the 301st CB placed as much as 50 tons of explosives a day to keep their dredges productive.

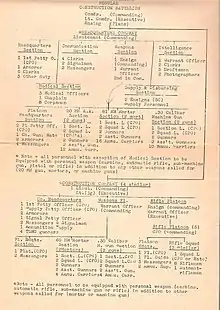

Organization

The primary Seabee unit was the battalion, composed of a headquarters company and four construction companies. Each company could do smaller jobs independently as they each had all the basic ratings for doing any job. Hq. Co. was made up primarily of fleet rates plus surveyors and draftsman. A CB's complement was 32 officers and 1,073 enlisted.

"By 1944 construction projects grew in scope and scale. Often more than one CB was assigned to a job. To promote efficient administrative control 3-4 battalions would be organized into a regiment, if necessary, two or more regiments were organized into a brigade. This happened on Okinawa where 55,000 Seabees deployed. All were under the Commander, Construction Troops, Commodore Andrew G. Bisset (CEC). He also had 45,000 U.S. Army engineers under his command making it the largest concentration of construction troops ever."[2]

The overall cost of all Seabee projects was $11 billion. At wars end they would number over 258,000. The NCF grew into 12 Naval Construction Brigades of: 54 Construction Regiments, 151 CBs, 39 Special CBs, 136 CB Maintaince Units, 118 CB Detachments, and 5 Pontoon Assembly Detachments.[62] In addition, many Seabees served in the NCDUs, UDTs, Cubs, Lions, Acorns and Marine Corps.

While the CB itself was versatile it was apparent that some units could be smaller and/or specialized for task specific units. "The first departure from the standard CB was the "Special" Construction Battalion, or the "CB Special". "Special" CBs were composed of stevedores and longshoremen who were badly needed for the unloading of cargo in combat zones. Many officers for "Specials" were recruited from the Merchant Marine (and commissioned as CEC) while stevedoring companies were the source of many of the enlisted. Soon, the efficiency of cargo handling in combat zones was on a par to that found in the most efficient ports in the U.S."[2] There were five battalions specialized in pontoons, barges, and causeways: 70th, 81st, 111th, 128th, 302nd.[63] The 134th & 139th CBs were made trucking units due to the transportation and logistic needs on Guam and Okinawa.

"Several types of smaller, specialized units were created. Construction Battalion Maintenance Units/CBMUs, a quarter the size of a CB were one. They were Public Works units intended to assume base maintenance of newly constructed bases. Another unit type was the Construction Battalion Detachment/CBD, of 6 to 600 men. CBDs did everything from running tire-repair shops to operating dredges. Many were tasked with the handling, launching, assembly, installation of pontoon causeways. Others were petroleum dets specializing in pipelines or petroleum facilities)."[2]

The Seabee

The Seabee's machinegun-toting bumblebee insignia was created by Frank J. Iafrate, a clerk at the Camp Endicott, Quonset Point, Rhode Island. Iafrate was known for being artistic and a lieutenant asked if he could do a "Disney style" Seabee insignia. He chose the bumblebee for his model. Image-wise they have more "heft" than the honeybee and "heft" suited the whole idea. He put three hours sketching: a sailor's cap, a uniform with petty officer ranks on each arm plus the tools and rates of the gunner's mate, machinist mate, and carpenter's mate. On each wrist he placed the CEC insignia. For a border he usedna letter Q for Quonset Point. He gave the design to the lieutenant. The lieutenant showed it to his captain, who sent it off to Adm. Moreell. The only change the Admiral requested was that the border be changed to a hawser rope in keeping with Naval tradition for Naval insignia.[64]

Flame throwing tanks, CWS: Flame Tank Group

During WWII Seabees modified/created all of the main armament flame throwing tanks that the USMC put in the field on Saipan, Tinian, Iwo Jima, and the U.S. Army on Okinawa. They were a weapon Japanese troops feared and the Marine Corps said was the best weapon they had in the taking of Iwo Jima.[67] After Okinawa the Army stated that the tanks had a psychological presence on the battlefield. U.S. troops preferred to follow them over standard armor for the fear they put in the enemy.[68]

Pacific field commanders had tried field modified mechanized flame throwers early on,[69] with the Marine Corps deciding to leave further development to the Army. The Navy had an interest in flame throwing and five Navy Mark I flamethrowers arrived in Hawaii in April 1944. The Navy deemed them "unsuitable" due to their weight and turned the over to the Army's Chemical Warfare Service.[70] In May a top secret composite unit was assembled at Schofield Barracks.[71] It was lead by Colonel Unmacht of the US Army Chemical Warfare Service, Central Pacific Area (CENPAC)[68][72] Col. Unmacht began the project with only the 43rd Chemical Laboratory Company. They modified the first light tank designating it a "Satan". The flame tank group was expanded with men from the 5th Marine tank battalion and 25 from the 117th CB.[71] The newly attached Seabees went over what the Army had created and concluded it was a little over engineered. They recommended reducing the number of moving parts from over a hundred to a half dozen.

V Amphibious Corps (VAC) wanted mechanized flamethrowing capabilities for the Marianas operations. VAC had ordered and received two shipments of Canadian Ronson F.U.L. Mk IV flamethrowers (30 flamethrowers in total) to field modify tanks. With a war to wage field modification was much quicker than going through official military procurement channels. The 117th CB was assigned to the upcoming Saipan operation. Col Unmacht worked out an arrangement to not only keep the 117th Seabees he had, but get more. Augmented by the additional Seabees, the group worked sun up to sundown and, with Seabee Can-do twenty-four M3s were modified to start the campaign.[72] The very first, made by the 43rd Co, was christened "Hells Afire".[73] The installation configuration of the flamethrower components limited the turret's traverse to 180°. As Satans were produced Colonel Unmacht had the Seabees conduct a comprehensive series of 40-hour classes on flame tank operation with first and second eschelon maintenance. First, for officers and enlisted of the Marine Corps and then later for the Army.[74][72] The Satans had a range of 40–80 yd (37–73 m) and were the first tanks to have the main armament swapped for flame throwers. They were divided between the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions for Siapan and Tinian with Tinian being more favorable to their use.[72]

- Four Seabees received commendations for their work from Lt. Gen. Holland M. Smith Commanding General(USMC) FMF Pacific.[71]

- At least 7 were awarded the Bronze Star.[73]

Mid-September the Army decided to officially form a CWS "Flame Thrower Group" with Col Unmacht requesting 56 additional Seabees.[73] The group included more Army CWS and 81st Ordnance men as well.[71] It was apparent that a larger flamethrower on a bigger tank would be more desirable, but very few tanks were available for conversion. Operation Detachment was next and Col Unmacht's group located eight M4A3 Sherman medium tanks for it. The Seabees worked to combine the best elements from three different flame units: the Ronson, the Navy model I and those Navy Mk-1s the Navy gave up.[71] MMS1c A.A. Reiche and EM2c Joseph Kissel are credited with designing the CB-H1. Installation required 150 lbs of welding rod, 1100 electrical connections, and cost between $20,000-25,000 per tank[71](adj. for inflation $288,000-$360,000 in 2019). The CB-H1 flamethrower operated on 300 psi which gave it a range of 400 ft (120 m) and could transverse 270°.[71] This model was quickly superseded by the CB-H2 that was far better.[75] EM2c Kissel and another Bee accompanied the tanks to oversee maintenance during the battle of Iwo Jima. Kissel filled in as an assistant driver/gunner with tank crews on 20 days of the operation.[73]

In November 1944, prior to the rave USMC reviews of Iwo Jima, the Fleet Marine Force had requested 54 mechanized flame throwers, nine for each of the Marine Corps Divisions[76] On Iwo the tanks all landed D-day and went into action on D+2, sparingly at first. As the battle progressed, portable flame units sustained casualty rates up to 92%, leaving few troops trained to use the weapon. More and more calls came for the Mark-1s to the point that the Marines became dependent upon the tanks and would hold up their assault until a flame tank was available.[68] Since each tank battalion had only four they were not assigned. Rather, they were "pooled" and would dispatch from their respective refueling locations as the battle progressed. One the 4th Division tanks had a 50 cal. machine gun coaxial to the flamethrower as well as 4 in (100 mm) concrete armor to counter placement of magnetic charges. Towards the end of the battle, 5th Marine tanks used between 5,000 to 10,000 US gal (19,000 to 38,000 L) gallons per day.[68]

For Okinawa the 10th Army decided that the entire 713th Tank Battalion would provisionally convert to flame. The Battalion was tasked to support both the Army and the Marine Corps assault. It was ordered to Schofield Barracks on Nov 10. There the Seabees supervised three officers and 60 enlisted of the 713th convert all 54 of their tanks to Ronsons.[76][77] The Ronsons did not have the range of either the CB-H1 or CB-H2.

In June 1945, the 43rd Chemical Lab. Co. had developed a stabilized flamethrower fuel (napalm). They oversaw CB construction of an Activating Plant that produced over 250,000 gallons.[73] The 713th went through 200,000 gallons on Okinawa. Also in June, the Army cancelled all further production orders for any more M4 Sherman's. This caused Under Secretary of War Robert Patterson to place an expedite on Col. Unmacht's production of flame tanks. They were given a "Triple A" procurement priority, the same given to the B-29 and the Atomic bomb projects.[78]

Another 72 tanks were ordered by the Marine Corps for the planned invasion of Japan[68] of which Col. Unmacht's crews had 70 ready by Victory over Japan Day. In total Unmacht's Flame Tank Group produced 354 tanks.[79]

The military did not have uniform terminology for referencing mechanized flamethrowers so there is some wording variation in documents. The Seabees produced 11 different models of flamethrowing tanks off three basic variations identified with a POA-CWS-H number[73]

"Primary" where the main armament was removed and replaced.

- The first eight had Navy CB-H1 or CB-H2 flamethrowers. US Army Chemical Corps variously identified these tanks as POA-CWS-H1,[73] (Pacific Ocean Area-Chemical Warfare Section-Hawaii) CWS-POA-H2, CWS-POA-H1 H2, OR CWS-"75"-H1 H2 mechanized flamethrowers. US Marine and US Army observer documents from Iwo Jima refer to them as the CB-Mk-1 or CB-H1.[80] Marines on the lines simply called them the Mark I.[80] The official USMC designation was "M4 A3R5".[80] The Japanese referred to them as M1 tanks and it is speculated that they did so due to a poor translation of "MH-1".[80]

- The next 54 tanks had Ronson flamethrowers. That made them the third tank variant produced. Army records identify them as POA-CWS-H1s.

- Some of these tanks were configured with an external 400-foot (120 m) long hose supplying a M2-2 portable flamethrower that ground troops could use.[80] This variation could throw some 60 ft (18 m). A drawback to this attachment was all the fuel it took to charge the hose line so it could fire diminished the tank's overall effectiveness. Army documents post-war refer to this variation as being a CWS-POA-H1.[80]

"Auxiliary" where the flame thrower was mounted coaxial to the main armament. Eighteen of the first generation model were on the way to the 10th Army on Okinawa, but the island was taken before they arrived, so they were given to the 3rd Marine Division tank battalion on Guam.[81]

- 75mm main armament with Ronson

- 75mm main armament H1a-H5a

- 105mm main armament with Ronson

- 105mm main armament with H1a-H5a USMC designation M4-A3E8. These would be at Inchon in 1950.[80]

In mid-1945 the Seabees started producing the second generation of these tanks. These H1a-H5a Shermans, with either 75mm or 105mm main armaments, were jointly referred to as CWS-POA-5s.

"Periscope Mount" This model was based upon work done by the U.S. Army at Fort Knox. The flame thrower was mounted through the assistant driver's hatch alongside their tank periscope which meant that the bow machine gun could be retained. 176 were produced.[82] Word spread that one of these tanks lost a crew when the flamethrower nozzle took a hit.[72] The Marine Corps did not want this design.[82]

- H1 periscope[82]

- H1A periscope[82]

- H1B periscope[82]

- Examples labeled POA-CWS-H1 and POA-CWS-H5 are on display at the Mahaffey Museum at Fort Leonard Wood Missouri.

- 5th Marine CB-H1 in action on D+22,[83]

- Example M42 B1E9

The Marines preferred the CB tanks to any produced in the U.S. at that time.[84] The Marine Corps and Army both felt that the flamethrowing tanks saved U.S. troops lives and kept the casualty numbers lower than they would have been had the tanks not been used.[72] They also agreed that they would need many for the invasion of the Japanese homeland.

Postwar the Army stood down the provisional 713th keeping no flame tanks.[80] The Marine Corps came close to doing the same. When Korea broke out they were able to put together nine CWS-POA-H5s from Pendelton and Hawaii. Together they formed a platoon, named the "Flame Dragons", in the 1st tank battalion.[85] They landed at Inchon in 1950 and were the only U.S. mechanized flame unit to be in Korea.[85]

- Col Unmacht 1946 Military Review flame tank article.[86]

Seabee Awards in the NCF

During WWII Seabees would be awarded 5 Navy Crosses, 33 Silver Stars, and over 2000 Purple Hearts. Many would receive citations and commendations from the Marine Corps. The most decorated officer was Lt. Jerry Steward (CEC): Navy Cross, Purple Heart with 3 Gold Stars, Army Distinguished Unit Badge with Oak leaf and the Philippine Distinguished Service Star. Another CEC with an unusual set of awards was Capt. Wilfred L. Painter: Legion of Merit with Combat "V" and 4 Gold Stars.

![]() Presidential Unit Citation USN/USMC :

Presidential Unit Citation USN/USMC :

- 75 men 3rd CB, Guadalcanal, USS Enterprise [87]

- 6th CB, Guadalcanal, 1st Marine Division [87]

- 202 men 33rd CB, Peleliu, 1st Marine Pioneers[87]

- 241 men, 73rd CB, Peleliu, 1st Marine Pioneers[87]

![]() U.S. Army Distinguished Unit Citation :

U.S. Army Distinguished Unit Citation :

- 3rd Naval Construction Detachment- Espirto Santo[87]

- 11th Special CB, Okinawa[87]

- 31st CB, Iwo Jima, 5th Marine Shore party Regiment[87]

- 33rd CB, Peleliu 1st Marine Pioneers[87]

- 58th CB, Vella Lavella[87]

- 62nd CB, Iwo Jima, V Amphibious Corps[87]

- 71st CB, Okinawa[87]

- 53 men 113th CB, PT boat Advance Base Construction Detachment, Balikpapan Borneo/Philippines[87]

- 133rd CB, Iwo Jima, 23rd Marine Regiment[87]

- 301st CB, Siapan, Tinian, Guam, Peleliu, Iwo Jima, Okinawa[87]

- CBMU 515, Guam, 22nd Marine Regiment[87]

- CBMU 617, Okinawa[87]

- CBMU 624, Okinawa[87]

- CBD 1006, Sicily[87]

![]() U.S.ARMY Meritorious Unit Commendation

U.S.ARMY Meritorious Unit Commendation

- 60th CB, Los Negros, 1st Cavalry Division[88]

Seabee Awards outside the NCF

Seabees serving outside the NCF received numerous awards as well. The Navy does not make a distinction for awards given inside or outside the NCF nor does it identify Seabees in the NCDUs or UDTs awards. Admiral Turner recommended over 60 Silver Stars and over 300 Bronze Stars with Combat "Vs" for the Seabees and other service members of UDTs 1-7[89] That was unpresendented in USN/USMC history.[89] For UDTs 3 and 4 at Guam and UDTs 5 and 7 at Tinian and all officers received silver stars and all enlisted received bronze stars with Combat "Vs".[90]

![]() Presidential Unit Citation USN/USMC

Presidential Unit Citation USN/USMC

- 3rd Battalion 18th Marines (18th CB) Tarawa, 2nd Marine Division[87]

- 12 men of 3rd Battalion 20th Marines (121st CB) Saipan and Tinian 4th Marine Division[87]

- Naval Combat Demolition Units assault force O Normandy[87]

- NCDU 11, NCDU 22, NCDU 23, NCDU 27

- NCDU 41, NCDU 42, NCDU 43, NCDU 44

- NCDU 45, NCDU 46, NCDU 128, NCDU 129

- NCDU 130, NCDU 131, NCDU 133, NCDU 137

- UDT 11 Bruni Bay, Borneo[87]

- UDT 11 Balikpapan, Borneo[87]

- 3rd Battalion 22nd Marines [1st Naval Construction Detachment(Bobcats), & A Company 3rd CB] Eniwetok[87]

- ACORN 14, Tarawa, 2nd Marine Division[87]

- Naval Combat Demolition Units force U Normandy[87]

- NCDU 25, NCDU 26, NCDU 28, NCDU 29

- NCDU 30, NCDU 127, NCDU 132, NCDU 134

- NCDU 135, NCDU 136, NCDU 139

- UDT 4, Guam[87]

- UDT 4, Leyte[87]

- UDT 4, Okinawa[87]

- UDT 7, Marianas[87]

- UDT 7, Western Carolina's[87]

The Seabee Record[91]

Post-war legacy

During the war many of the bases the Seabees built were disassembled for the materials to be reused in new bases closer to the front. However, the airfields could not be moved and remained post war. The Seabees built or repaired dozens across the Pacific. Today, after upgrades and modernization, many are still in use or remain usable.

Pacific:

- Abemama Atoll Airport (95th CB)

- Alexai Point Army Airfield and Casco Cove Coast Guard Station (114th & 138th CBs)

- Andersen Air Force Base (5th Construction Brigade)

- Awase Airfield (36th CB)

- Bauerfield International Airport ( 1st CB)

- Bonriki International Airport (3rd Bn 18th Marines)

- Bucholz Army Airfield (109th CB with CBs 74, 107, & 3rd Bn 20th Marines)

- Carney Airfield used until 1970's (CB 14 abandoned)

- Central Field (Iwo Jima) (CBs 31,62, 133)

- Daniel Z. Romualdez Airport (88th CB)

- Dulag Airfield (61st CB)

- East Field (Saipan) (51st CB) The airfield is on the National Register of Historic Places as the "Isley Field Historic District", and is part of the National Historic Landmark District on Saipan.

- Emirau Airport (out of service but remains usable)

- Enewetak Auxiliary Airfield (110th CB)

- Falalop Airfield (51st CB)

- Faleolo International Airport (CB 1)

- Finschhafen Airport (60th CB and U.S. Army)

- French Frigate Shoals Airport (B Co. CB 5)

- Freeflight International Airport (3rd Bn 20th Marines & 109th CB)

- Funafuti International Airport (2nd CB detachment)

- Fuaʻamotu International Airport (1st CB)

- Guasopa Airport/Woodlark Airfield (60th CB)

- Guam International Airport/NAS Agana (103rd CB, 5th Construction Brigade)

- Guiuan Airport (61st & 93RD CBs)

- Hawkins Field (3rd Bn 18th Marines, CBs 74 & 98)

- Haleiwa Fighter Strip (14th CB)

- Henderson Field (Midway Atoll)

- Hihifo Airport (Seabees)

- Honiara International Airport/ Henderson Field (Guadalcanal) (CBs 6, 14, 18)

- Honolulu International Airport NAS Honolulu – John Rodgers Field (5th CB with CBs 13, 64, & 133)

- Johnston Island Air Force Base (CBs 5, 10, & 99)

- Kornasoren Airport (Yeburro Airfield) 95th CB

- Kukum Field used until 1969 (CBs 6, 26, 46, 61)

- La Tontouta International Airport (seabees)

- Leo Wattimena Airport

- Losuia Airport/Kiriwina Airfield (60th CB)

- Luganville Airfield used until mid-1970's (40th CB)

- Mactan-Benito Ebuen Air Base (54th CB, Cub 51)

- Majuro Airfield (100th CB used 20 years postwar)

- Marpi Point Field (51st CB & CBMU 614) The airfield is on the National Register of Historic Places as the "Isley Field Historic District", and is part of the National Historic Landmark District on Saipan.

- Marine Corps Air Station Kaneohe Bay (CBs 56, 112, 74)

- Momote Airport (40th CB)

- Mono Airport (87th CB)

- Mopah International Airport (55th CB)

- Munda Airport (CBs 24, 47, 63, 7)

- Nanumea Airfield (16th CB)

- Nausori International Airport ( Seabees)

- Naval Base Guam (5th Naval Construction Brigade)

- Naval Air Base Tanapag (39th CB), site of NTTU Saipan (Naval Technical Training Unit – CIA, used postwar until 1962)[92]

- Naval Air Station Kaneohe (CBs 56, 74, 112)

- Naval Station Sangley Point is now Danilo Atienza Air Base(PAF) and Naval Base Cavite(PN) (77th CB,12th Construction Regiment)

- Nissan Island Airport (93rd CB)

- North Field (Tinian) The airfield is an element of the Tinian National Historic Landmark District. (6th Construction Brigade) (NMCB 28)

- Northwest Field (Guam) (53rd CB semi-abandoned)

- Nouméa Magenta Airport (11th CB)

- Nukufetau Airfield (Motolalo Airfield) 16th CB

- Ondonga Airfield (CBs 37 & 82)

- Orote Field (5th Naval Construction Brigade)

- Palmyra (Cooper) Airport (Seabees)

- Palikulo Bay Airfield ( 7th & 15th CBs)

- Penrhyn atoll has the Tongareva Airport (Seabees)

- Piva Airfield ( CBs 25, 53, 71, & 74)

- Point Barrow Naval Arctic Research Laboratory Airfield (CBD 1058) Runway and two hangars intact 2014

- Puerto Princesa International Airport (CB 84)

- Rota International Airport (48th CB)

- Santo-Pekoa International Airport ( CBs 3, 7, 15)

- Saipan International Airport (3rd Bn 20th Marines/CB 121) The airfield is on the National Register of Historic Places as the "Isley Field Historic District", and is part of the National Historic Landmark District on Saipan.

- South Field (Iwo Jima) (CBs 31, 64, & 133 abandoned post-war)

- Segi Point Airfield (47th CB)

- Seghe Airport (47th CB)9

- Tontouta Air Base (53rd CB)

- Torokina Airfield (CBs 25, 53, 71, & 75)

- Umiat Airport (CBD 1058)

- Wake Island (85th CB)

- West Field (Tinian) Today is Tinian International Airport. (6th Construction Brigade)

- Yandina Airport (CBs 33 & 35)

- Yomitan Auxiliary Airfield (71st & 87th CB)

- Yonabaru Airfield ( 145th CB)

- Atlantic

- Naval Air Station Port Lyautey/Kenitra Air Base (120th CB)

- Naval Communication Station Sidi Yahya (120th CB)

- Military installations WWII

- Casco Cove Coast Guard Station (22nd CB)

- Lombrum Naval Base (CBs 11, 58, 71)

- Naval Base Guam (5th Naval Brigade)

- Subic Bay Naval Station now Subic Bay Freeport Zone

- Military installations built post-war

- Naval Air Station Cubi Point now Subic Bay International Airport (MCBs 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 11) 1951–56

- TACAN Naval Station Adak[93] 1959 (MCB 10)

- LORAN Station Grand Turk, 1957–59 (MCB 7)

- LORAN Station San Salvador Island, 1957–59 (MCB 7)

- Marine Corps Air Station Futenma 1957 (MCB 3 plus detachment MCB 2)

- Naval Communications Station Nea-Makri, 1962

- Nakhon Phanom Royal Thai Navy Base (MCB 3) 1962

- Royal Thai Air Base Nam Phong (NMCB 5)

- Minami Torishima Airport (MCB 9) 1964

- Camp Hansen (MCBs 3, 9, 11) 1965

- Chu Lai Air Base now is Chu Lai International Airport (MCB 10) 1965

- Quảng Trị Combat Base (Seabees) 1967

- Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia (NMCBs 1, 40, 62, 71, 133 & ACB 2) 1971–82

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States Navy Seabees. |

- Camp Allen

- Camp Endicott

- Camp Peary

- Civil Engineer Corps

- Leapfrogging (strategy)

- Military engineering of the United States

- Seabees Memorial

- Underwater Demolition Team

- United States Navy Argus Units with Acorn Units

- 17th Marine Regiment (Engineer) 19th CB

- 18th Marine Regiment (Engineer) 18th CB

- 19th Marine Regiment (Engineer) 25th CB

- 20th Marine Regiment (Engineer) 121st CB

Notes

- On Johnson atoll the 1st Marine Defense Battalion detachment named each of its batteries. One them was made up of four 3" AA guns and called the "Seabee battery".[94]

- "Cumshaw" ("Cumshaw definition". Merrian Webster.) "moonlight procurement",

References

- Rogers, J. David. "USN Seabees During World War II" (PDF). Missouri University of Science and Technology. p. 8. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- History of the Seabees, Command Historian, Naval Facilities Engineering Command (Report). 1996. p. 13. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- 105th NCB, BuDocks, Dept. of the Navy 1946, Seabee Museum, Port Hueneme, CA.

- Henry, Mark (2002), The U.S. Navy in WWII, Elite 80, Osprey Publishing, p. 24

- "This Date in Seabee History", Seabee Online Magazine, 11 February 2018

- "Seabee History: Introduction". Naval History and Heritage Command. 17 February 2017.

- Seabee History, Formation of the Seabees in World War II, NHHC, Navy Dept. Library online, April 16, 2015

- "Part I". Building the Navy's Bases in World War II. Volume I. 1947 – via Naval History and Heritage Command.

- NAVFAC website Washington Navy Yard, DC

- Camp Lee-Stephenson Monument at Quoddy Village, Eastport, Maine, CEC/Seabee Historical Foundation

- "Seabee History: Formation of the Seabees and World War II". Naval History and Heritage Command. 16 April 2015.

- Pearl Harbor and the Outlying Islands, Building the Navy's Bases in WWII, GPO Washington DC, 1947, p. 148

- 136th Seabee cruisebook, 136th CB, Yokouska, Japan Oct 1945, Seabee Museum Archives, Port Hueneme, CA.

- "Chapter XVIII: Bases in South America and the Caribbean Area, Including Bermuda". Building the Navy's Bases in World War II: … Volume II – via HyperWar.

- How The Seabees Won World War II for America, by Warfare History Network, January 12, 2020, p. 4,5 ,

- NCB 3 History, NCB History List, NHHC, Seabee Museum Archives, Port Hueneme, CA

- Section F & G, USS Enterprise (CV-6) War History, 7 December 1941 to 15 August 1945, War Damage Report 59, The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal 12-15 NOV. 1942, NHHC, U.S. Hydrographic Office, 1947, p. 17-26

- Stafford, Edward P. (1962). "XIII: The Slot". The Big E: The Story of the USS Enterprise. Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press. p. 214. ISBN 1-55750-998-0.

- Leckie, Robert (1965). "Part V - Crux, chapter 2". Challenge For the Pacific: The Bloody Six-Month Battle of Guadalcanal. New York: Perseus Book Group. p. 321. ISBN 0-306-80911-7.

- Stafford, Edward P. (1962). The Big E: The Story of the USS Enterprise. Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press. p. 546. ISBN 1-55750-998-0.

- Seabees Repair Carrier During Sea Battle (Technical report). News Letter Bureau of Aeronautics Navy Department. 1 February 1943. pp. 15–16. 187.

- part 5, 27th Naval Construction Battalion cruisebook, 1946, Seabee Museum Archives, Port Hueneme, CA, p.41

- "US Navy Divers in World War 2". WWII Forums.

- "That One Time the Seabees Found a Submarine", Julius Lacano, Seabee Museum, Port Hueneme, CA

- Task Force 70, 7th Fleet, United States Navy in Australia during WWII, Peter Dunn, oz@war

- The Forgotten Fifty Five, NCB93: 113RD Seabees detachment assigned to PT Squadrons, Seabees93.net

- An Improvised Air Force, The Mopping-up Begins in the West, Cape Gloucester: The Green Inferno, Bernard C. Nalty, Marines in World War II Commemorative Series, Marine Corps Historical Center, Building 58, Washington Navy Yard, Washington, D.C. 20374-5040, 1994

- Cape Gloucester: Mud-bogged roads, Sherman tanks, and a Seabee “Aviator”, Julius Lacano, Seabee Museum, Port Hueneme, Ca

- Seafoam, 61st CB cruisebook, 14 April 1945, p. 46

- 2nd Anniversary 1945 84th Battalion Seabees, Seabee Museum, Port Hueneme Ca., p. 196

- "August 6, 1945, This Week in Seabee History", Dr. Frank A. Blazich Jr., NHHC, Seabee Museum, Port Hueneme, CA

- Olsen, A.N. (2011). The King Bee. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781612511085. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- Morelock, Jerry D. (September 2014). "U.S. Navy Seabees". Armchair General. Retrieved 14 December 2019 – via HistoryNet.

- Issue 20, 16 May 1944, Seabee News Service, Budocks, p. 1

- Blazich, Frank A. (26 November 2014). "Harbor-Base-Neighbors: When the Navy Came to Port Hueneme, 1942–1945, and Beyond". Seabees Online. Navy Facilities Engineering Command. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). World War II Pacific Island Guide: A Geo-military Study. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 78. ISBN 9780313313950. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- "Chapter XXV: Campaign in the Solomons". Building the Navy's Bases in World War II. Vol. II. p. 264. Retrieved 18 October 2017 – via HyperWar.

- "Chapter V: Procurement and Logistics for Advance Bases". Building the Navy's Bases in World War II: … Volume II. p. 120. Retrieved 18 October 2017 – via HyperWar.

- "Chapter VI: Advance Base Units – LIONS, CUBS, ACORNS". The Logistics of Advance Bases. Naval History and Heritage Command, The Base Maintenance Division. 7 November 2017. pp. 75–97. OP-30 [OP-415]. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Acorn 51 cruise book (PDF). Port Hueneme, CA: Seabee Museum.

- Rogers, J. David. "U.S. Navy Seabees During World War II" (PDF). Missouri University of Science and Technology. p. 67. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- Lion 1, "Beans, Bullets, and Black Oil", The Story of Fleet Logistics Afloat in the Pacific During World War II, RADM Worrall USN (Retired),1952, Naval Heritage and History Command website, Aug 2017, p.50

- "Chapter XXIV: Bases in the South Pacific". Building the Navy's Bases in World War II: … Volume II – via HyperWar.

- The Amphibians came to Conquer, U. S. Marine Corps, DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY, Headquarters United States Marine Corps, Washington, DC 20380-0001, PCN – 140- 12991900, p. 467

- 34th Naval Construction Battalion, NHHC, Seabee Museum Archives, Port Hueneme, California.

- "Argus Unit 1". United States Navy Argus Unit Historical Group. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "Banika (and Pavuvu), Russell (or Russel) Islands". History of the 93rd Seabees Battalion. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- John R. (20 November 2009). "Tarawa Seabees". DiscussionApp. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- Blazich, Frank A. (12 May 2017). "This Week in Seabee History (Week of May 14)". Seabees Online. Navy Facilities Engineering Command. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- This Week in Seabee History, July 29-AUGUST 4, NHHC, Dr Frank Blazich, Seabee Museum, Port Hueneme, CA.

- CBMU 615 history file (PDF). Port Hueneme, CA: Seabee Museum.

- The Million Dollar Point of Vanuatu, Kaushik Patowary, Amusing Planet web site, November 2016

- Seabee Junkyard: A holistic and locally inclusive approach to site management and interpretation, Kalle Applegate Palmer, online Museum of Underwater Archaeology, 2014

- "U.S. Navy Enlisted Rating Structure". bluejacket.com. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- U.S. Naval Construction Battalions, Administration Manual. U.S. Gov. January 1944. pp. 27–30. Retrieved 18 October 2017 – via google books.

- "Seabee", Henry B. Lent, The MacMillan Company, New York, 1944, pp. 65, 130

- "US Navy Divers in World War 2". WWII Forums.

- Water Temperature Table of the Alaska Coast, National Centers for Environmental Information, last updated: Sat Jun 06, 23:02:52 UTC 2020

- Navy Divers, Bureau of Naval Personnel Information Bulletin, All Hands, September 1944, p. 26-30, Evansville Vanderburgh Public Library, Indiana

- Issue 20, 16 May 1944, Seabee News Service, Budocks, p. 11

- WWII Navy Diver helped recover bodies at Pearl Harbor, The Daily Herald, Everett, WA, Jan 28, 2017, Heraldnet.com

- Rottman 2008, pp. 31–32.

- Rottman 2002, p. 31.

- "The Origin of the Seabees". NSVA.org. Navy Seabee Veterans of America, Inc. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- LVT4 Landing Vehicle, Tracked, Unarmored (Mark IV), John Pike, GlobalSecurity.Org, July 2011, paragraph 5[LVT4 Landing Vehicle, Tracked, Unarmored (Mark IV)]

- 117th Naval Construction Battalion Cruisebook, NHHC, Seabee Museum website, Port Hueneme CA, Jan. 2020, p. 22,23

- Chapter: the Bitter End, CLOSING IN: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima, Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret), History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., 1994, p.37

- Kelber, Brookes E.; Birdsell, Dale (1990), "Chapter XV, The Flame Thrower in the Pacific: Marianas to Okinawa" (PDF), United States Army in World War II, The Technical Services, The Chemical Warfare Service; Chemicals in Combat, Center of Military History United States Army, Washington DC, pp. 558–583, 586

- Kelber and Birdsall (1966) p 558

- Armored Thunderbolt: The U.S. Sherman in World War II, Steve Zaloga, 2008

- "New Tanks for Old", U.S. Navy Civil popEngineer Corps Bulletin, Bureau of BuDocks, Dept. of the Navy, Vol 2 NAVDOCKS P-2 (14), p. 51 on line 21, January 1948

- CHAPTER XV, The Flame Thrower in the Pacific: Marianas to Okinawa, WWII Chemical in Combat, Dec 2001, p. 558

- Unmacht (CWS), Col Geo. F. (April 1948), "Flame Throwing Seabees", United States Naval Institute Proceedings, 74 (342), pp. 425–7

- Dr. Frank A. Blazich Jr., This week in Seabee History (Week of Oct. 23), U.S. Navy Seabee Museum, Port Hueneme, CA.

- New Tanks for Old, USN CEC Bulletin Vol. 1, No. 1, Dec. 1946, BuDocks Navy Deot, U.S. GPO, Washington D.C., p. 53.

- Zaloga 2013, p. 29.

- 1st Lt. Patrick J. Donahoe (1994), "Flamethrower Tanks on Okinawa", Armor, U.S. Army Armor Center, Fort Knox (Jan-Feb 1994), p. 6

- History Friday: Mechanized Flame Weapons from the invasion That Never Happened, Chicagoboyz Blog archive, Trent Telenko, Nov 2013, chicagoboyz.net

- Montcastle, John W. (2016), Flame On, U.S. Incendiary Weapons, 1918-1945, StackpoleBooks, Mechanicburg, PA., p. 142 #33, ISBN 9780811764919

- Telenko, Trent (30 August 2013), "History Friday: Technological Surprise & the Defeat of the 193rd Tank Battalion at Kakuza Ridge", Chicago Boyz Blog archive

- The Chemical Warfare Service: From the Laboratory to the Field, L.B. Brophy, W.D. Miled, R.C. Cochrane, of Military History, U.S. Army, Washington D.C., U.S. GPO, Washington D.C., 1959, p. 153

- Zaloga, Steven J. (2013), US Flamethrower Tanks of World War II, Bloomsbury, ISBN 9781780960272

- "New Footage: Flame Tanks on Iwo Jima (Silent)", Marine Corps Film Archive – via youtube

- "Commandant USMC Memorandum for the record: 22 Jan, 1945, RG 127, File #2000,NA"

- Now They're Flame Dragons, chapt 50, Flame Dragons of the Korean War, Jerry Ravin & Jack Carty, Turner Publishing, 412 Broadway, Paducah, KY, 2003, p.222

- Flamethrower Tanks in the Pacific Ocean Areas, COLONEL GEORGE F. UNMACHT, Chemical Warfare Service Chemical Officer. United States Army, Forces. Middle Pacfic, Military Review, March 1946, Vol 25 No 12, p. 44-51, Combined Arms Research Library, created 2010-09-10,

- Naval History and Heritage Command website, Navy and Marine Corps Awards Manual [Rev. 1953] Part 2 – Unit Awards, 31 Aug 2015

- Meritorious Unit Commendation NCB 60, General Orders No. 77 of the Department of the Army, 5 September 1951, U.S Navy Civil Engineer Corps bulletin, Vol. 6 No. 1, Jan 1952

- America's First Frogman, Elizabeth K. Bush, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, Chapt. 7

- Naked Warriors, Cdt. Francis Douglas Fane USNR (Ret.), St. Martin's Press, New York, 1996, pp. 122, 131

- Appendix The Seabee Record, Building the Navy's Bases in WWII, History of BuDock and the CEC 1940-46, GOP, Washington D.C.

- Technical Training Unit (NTTU), 2003 Pacific World CNMI Tanapag website, Towson University

- MCB 10 1959 cruisebook, p. 18/53, Seabee Museum, Port Hueneme, CA.

- Pacific Island Forts web page, Johnston Atoll, Pete Payette, 23 August 2013

Bibliography

- Building the Navy's Bases in World War II: History of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineer Corps, 1940–1946, Volumes I & II. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. 1947 – via Naval History and Heritage Command.(via HyperWar)

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2008). U.S. Marine Corps WWII Order of Battle. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-31906-8.

- Zaloga, Steven J. (2013), US Flamethrower Tanks of World War II, New Vanguard, Osprey, ISBN 9781780960272

- Kelber, Brookes E.; Birdsell, Dale (1990) [1966], "Chapter XV, The Flame Thrower in the Pacific: Marianas to Okinawa" (PDF), The Chemical Warfare Service: Chemicals in Combat, United States Army in World War II, Center of Military History United States Army, Washington DC – via Hyperwar Foundation

Further reading

- Lions, Cubs, Oaks, Acorns; United States Naval Administration in WWII

- Operation Crossroads: Composition of Joint Task Force One. Naval History and Heritage Command. 13 April 2015.

- "US Navy War Diaries: Carrier Aircraft Service Unit 44, ACORN 35 & ACORN 39". casu44.com.

- Office of Naval History (1948), Glossary of U.S. Naval Code Words NAVEXOS P-474, Washington, DC: U.S. Gov. Printing Office

- U.S. Naval Construction Battalions, Administration Manual. January 1944. p. 24.

- Huie, William Bradford (1997) [1944]. Can Do!: The Story of the Seabees. Bluejacket Books. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. "Can Do" William Bradford Huie, E.P Dutton Press, 1944 University of Michigan Library website

- Huie, William Bradford (2012) [1945]. From Omaha to Okinawa – The Story of the Seabees. Bluejacket Books. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

- Nichols, Gina (2006). The Seabees at Port Hueneme. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

- OPNAV Notice 1650, Master List of Unit Awards and Campaign Medals, Dept. of the Navy, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Washington, DC

External links

- Official website

- U.S. Navy Seabee Museum Online Reading Room

- Seabee Unit Histories and Cruisebooks at the Seabee Museum

- Seabee History, Naval History & Heritage Command

- Seabee & CEC Historical Foundation

- Seabee Online: official online magazine of the Seabees

- Seabees. Department of the Navy. Bureau of Yards and Docks (c. 1944)

- Seabees Report: European Operations (1945)

- The Marston Mat and Seabee

- The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia