Sex reassignment surgery (male-to-female)

Sex reassignment surgery for male-to-female involves reshaping the male genitals into a form with the appearance of, and as far as possible, the function of female genitalia. Before any surgery, patients usually undergo hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and, depending on the age at which HRT begins, facial hair removal. There are associated surgeries patients may elect to undergo, including vaginoplasty, facial feminization surgery, breast augmentation and various other procedures. Additionally, a growing number of trans people and activists have voiced the opinion that gender confirmation surgery is a much more preferable term to use, citing its more accurate description of the procedures' intentions and effects.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Transgender topics |

|---|

|

|

History

Lili Elbe was the first known recipient of male-to-female sex reassignment surgery, in Germany in 1930. She was the subject of four surgeries: one for orchiectomy, one to transplant an ovary, one for penectomy, and one for vaginoplasty and a uterus transplant. However, she died three months after her last operation.

Christine Jorgensen was likely the most famous recipient of sex reassignment surgery, having her surgery done in Denmark in late 1952 and being outed right afterwards. She was a strong advocate for the rights of transgender people.

Another famous person to undergo male-to-female sex reassignment surgery was Renée Richards. She transitioned and had surgery in the mid-1970s, and successfully advocated to have transgender people recognized in U.S sports.

The first physician to perform sex reassignment surgery in the United States was Los Angeles-based urologist Dr. Elmer Belt, who quietly performed operations from the early 1950s until1968. In 1966 Johns Hopkins University opened the first sex reassignment surgery clinic in America. The Hopkins Gender Identity Clinic was made up of two plastic surgeons, two psychiatrists, two psychologists, a gynecologist, a urologist, and a pediatrician.

In 1997, Sergeant Sylvia Durand became the first serving member of the Canadian Forces to transition from male to female, and became the first member of any military worldwide to transition openly while serving under the Flag. On Canada Day of 1998, the military changed her legal name to Sylvia and changed her sex designation on all of her personal file documents. In 1999, the military paid for her sex reassignment surgery. Durand continued to serve and was promoted to the rank of Warrant Officer. When she retired in 2012, after more than 31 years of service, she was the assistant to the Canadian Forces Chief Communications Operator.

In 2017, for the first time, the United States Defense Health Agency approved payment for sex reassignment surgery for an active-duty U.S. military service member. The patient, an infantry soldier who identifies as a woman, had already begun a course of treatment for gender reassignment. The procedure, which the treating doctor deemed medically necessary, was performed on November 14 at a private hospital, since U.S. military hospitals lack the requisite surgical expertise.[2]

Genital surgery

When changing anatomical sex from male to female, the testicles are removed (castration), and the skin or foreskin and penis is usually inverted, as a flap preserving blood and nerve supplies (a technique pioneered by Sir Harold Gillies in 1951), to form a fully sensitive vagina (vaginoplasty). A clitoris fully supplied with nerve endings (innervated) can be formed from part of the glans of the penis. If the patient has been circumcised (removal of the foreskin), or if the surgeon's technique uses more skin in the formation of the labia minora, the pubic hair follicles are removed from some of the scrotal tissue, which is then incorporated by the surgeon within the vagina. Other scrotal tissue forms the labia majora.

In extreme cases of shortage of skin, or when a vaginoplasty has failed, a vaginal lining can be created from skin grafts from the thighs or hips, or a section of colon may be grafted in (colovaginoplasty).

Surgeon's requirements, procedures, and recommendations vary enormously in the days before and after, and the months following these procedures.

Since plastic surgery involves skin, it is never an exact procedure. Cosmetic refining to the outer vulva is sometimes required. Some surgeons prefer to do most of the crafting of the outer vulva as a second surgery, when other tissues, blood and nerve supplies have recovered from the first surgery. This relatively minor surgery, which is usually performed only under local anaesthetic, is called labiaplasty.

The aesthetic, sensational, and functional results of vaginoplasty vary greatly. Surgeons vary considerably in their techniques and skills, patients' skin varies in elasticity and healing ability (which is affected by age, nutrition, physical activity and smoking), any previous surgery in the area can impact results, and surgery can be complicated by problems such as infections, blood loss, or nerve damage.

Supporters of colovaginoplasty state that this method is better than use of skin grafts for the reason that colon is already mucosal, whereas skin is not. Lubrication is needed when having sex and occasional douching is advised so that bacteria do not start to grow and give off odors.

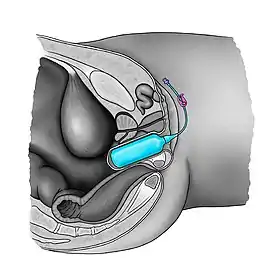

Because of the risk of vaginal stenosis (the narrowing or loss of flexibility of the vagina),[3][4] any current technique of vaginoplasty requires some long-term maintenance of volume by the patient using a vaginal expander,[5][6] or vaginal dilation using graduated dilators to keep the vagina open.[7][8][9] Penile-vaginal penetration with a sexual partner is not an adequate method of performing dilation. Daily dilation of the vagina for six months in order to prevent stenosis is recommended among health professionals.[4] Over time, dilation is required less often, but it may be required indefinitely in some cases.[9]

Regular application of estrogen into the vagina, for which there are several standard products, may help, but this must be calculated into the total estrogen dose. Some surgeons have techniques to ensure continued depth, but extended periods without dilation will still often result in reduced diameter (vaginal stenosis) to some degree, which would require stretching again, either gradually, or, in extreme cases, under anaesthetic.

With current procedures, trans women are unable to receive ovaries or a uterus. This means that they are unable to bear children or menstruate, and that they will need to remain on hormone therapy after their surgery to maintain female hormonal status and features.

Other related procedures

Facial feminization surgery

Occasionally these basic procedures are complemented further with feminizing cosmetic surgeries or procedures that modify bone or cartilage structures, typically in the jaw, brow, forehead, nose and cheek areas. These are known as facial feminization surgery or FFS.

Breast augmentation

Breast augmentation is the enlargement of the breasts. Some trans women choose to undergo this procedure if hormone therapy does not yield satisfactory results. Usually, typical growth for trans women is one to two cup sizes below closely related females such as the mother or sisters.[10] Oestrogen is responsible for fat distribution to the breasts, hips and buttocks, while progesterone is responsible for developing the actual milk glands. Progesterone also rounds out the breast to an adult Tanner stage-5 shape and matures and darkens the areola.

Voice feminization surgery

Some MTF individuals may elect to have voice surgery, which alters an individual's vocal range or pitch. However, this procedure carries a risk of impairing a trans woman's voice forever. Since estrogen alone does not alter a person's vocal range or pitch, some people take the risk that comes along with voice feminization surgery. Other options, like voice feminization lessons, are available to people wishing to speak with less masculine mannerisms.

Tracheal shave

A tracheal shave procedure is also sometimes used to reduce the cartilage in the area of the throat and minimize the appearance of the Adam's apple in order to assimilate to female physical features.

Buttock augmentation

Some MTF individuals will choose to undergo buttock augmentation because anatomically, male hips and buttocks are generally smaller than those presented on a female. If, however, efficient hormone therapy is conducted before the patient is past puberty, the pelvis will broaden slightly, and even if the patient is past their teen years, a layer of subcutaneous fat will be distributed over the body, rounding contours. Trans women usually end up with a waist to hip ratio of around 0.8, and if estrogen is administered at a young enough age "before the bone plates close", some trans women may achieve a waist to hip ratio of 0.7 or lower. The pubescent pelvis will broaden under estrogen therapy even if the skeleton is anatomically masculine.

See also

- List of transgender-related topics

- Sex reassignment surgery

- Sex reassignment surgery (female-to-male)

- Uterus transplantation

References

- Clements, KC (2018). "What to Expect from Gender Confirmation Surgery". www.healthline.com. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- Kube, Courtney (November 14, 2017). "Pentagon to pay for surgery for transgender soldier". NBC News.

- Lynne Carroll, Lauren Mizock (2017). Clinical Issues and Affirmative Treatment with Transgender Clients, An Issue of Psychiatric Clinics of North America, E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 111. ISBN 978-0323510042. Retrieved January 8, 2018.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Abbie E. Goldberg (2016). The SAGE Encyclopedia of LGBTQ Studies. Sage Publications. p. 1281. ISBN 978-1483371290. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- Coskun, Ayhan; Coban, Yusuf Kenan; Vardar, Mehmet Ali; Dalay, Ahmet Cemil (10 July 2007). "The use of a silicone-coated acrylic vaginal stent in McIndoe vaginoplasty and review of the literature concerning silicone-based vaginal stents: a case report". BMC Surgery. 7 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2482-7-13. PMC 1947946. PMID 17623058.

- Barutçu, Ali; Akgüner, Muharrem (November 1998). "McIndoe Vaginoplasty with the Inflatable Vaginal Stent". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 41 (5): 568–9. doi:10.1097/00000637-199811000-00020. PMID 9827964.

- Jerry J. Bigner, Joseph L. Wetchler (2012). Handbook of LGBT-Affirmative Couple and Family Therapy. Routledge. p. 307. ISBN 978-1136340321. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

Van Trostenburg (2009) stresses the need to maintain dilation and hygiene for the newly created vagina and tissues left vulnerable to infections that may result from surgery. He further notes that transgender women and their male sexual partners have to be advised about vaginal intercourse, since the newly created vagina is physiologically different than a biological vagina.

CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Arlene Istar Lev (2013). Transgender Emergence: Therapeutic Guidelines for Working with Gender-Variant People and Their Families. Routledge. p. 361. ISBN 978-1136384882. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

Vaginoplasty surgery increases the size of the vagina, though not without surgical complications, and often requires repeated dilation of the vaginal opening so that it remains open.

- Laura Erickson-Schroth (2014). Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource for the Transgender Community. Oxford University Press. p. 280. ISBN 978-0199325368. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

The surgeon will also provide a set of vaginal dilators, used to maintain, lengthen, and stretch the size of the vagina. Dilators of increasing size are regularly inserted into the vagina at time intervals according to the surgeon's instructions. Dilation is required less often over time, but it may be recommended indefinitely.

- "The Young M.T.F. Transsexual - The Gender Centre INC". gendercentre.org.au. Retrieved 2020-02-24.