Transgender rights in the United States

Transgender rights in the United States vary considerably by jurisdiction as the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) has only once ruled directly on transgender rights, in 2020; regarding the applicability of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act 1964, in the case of R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, SCOTUS held that Title VII protections on sex discrimination in Employment extend to Transgender Employees.

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT rights |

|---|

|

| lesbian ∙ gay ∙ bisexual ∙ transgender |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Transgender topics |

|---|

|

|

Birth certificates are typically issued by the Vital Records Office of the state (or equivalent territory, or capital district) where the birth occurred, and thus the listing of sex as male or female on the birth certificate (and whether or not this can be changed later) is regulated by state (or equivalent) law. However, federal law regulates sex as listed on a Consular Report of Birth Abroad, and other federal documents that list sex or name, such as the U.S. passport and Certificate of Naturalization. Laws concerning name changes in U.S. jurisdictions are also a complex mix of federal and state rules. States vary in the extent to which they recognize transgender people's gender identities, often depending on the steps the person has taken in their transition (including psychological therapy, hormone therapy), with some states making sex reassignment surgery a pre-requisite of recognition.

As of February 2019, Congress has not codified any laws specifically protecting transgender people from discrimination in employment, housing, healthcare, and adoption, but some lawsuits argue that the Equal Protection Clause of the federal constitution or federal laws prohibiting discrimination based on gender should be interpreted to include transgender people and discrimination based on gender identity. U.S. President Barack Obama issued an executive order prohibiting discrimination against transgender people in employment by the federal government and its contractors.[1] In 2016, the Departments of Education and Justice issued a letter to schools receiving federal funding that interpreted Title IX protection to apply to gender identity and transgender students, advising schools to use a student's preferred name and pronouns and to allow use of bathrooms and locker rooms of the student's gender identity.[2] Recognition and protection against discrimination is provided by some state and local jurisdictions to varying degrees.

The SCOTUS decision in Obergefell v. Hodges established that equal protection requires all jurisdictions to recognize same-sex marriages, giving transgender people the right to marry regardless of whether their partners are legally considered to be same-sex or opposite-sex. The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, of 2009, added crimes motivated by a victim's actual or perceived gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability to the federal definition of a hate crime. However, only some states and territories include gender identity in their hate crime laws.

Non-binary or genderqueer people may seek legal recognition of a gender identity other than that indicated by their birth sex; in 2016, Oregon became the first state to legally recognize non-binary people.[3] When a person's gender is not officially recognized, they may seek associated changes, such as to their legal name, including on their birth certificate.

Marriage

In Obergefell v. Hodges, SCOTUS ruled that people have a right to marry without regard to sex. While this is commonly understood as a ruling allowing same-sex marriage, it also meant that a person's sex, whether assigned at birth or recognized following transitioning, can not be used to determine their eligibility to marry. Prior to this ruling, the right of transgender people to marry was often subject to legal challenge — as was the status of their marriages after transitioning, particularly in cases where an individual's birth sex was interpreted to mean a same-sex marriage had taken place.[4]

Cases

In 1959, Christine Jorgensen, a trans woman, was denied a marriage license by a clerk in New York City, on the basis that her birth certificate listed her as male;[5][6] Jorgensen did not pursue the matter in court. Later that year, Charlotte McLeod, another trans female who underwent sex reassignment surgery, married her husband Ralph H. Heidel in Miami. She did not mention her birth sex, however, or the fact she was still legally male. The first case in the United States which found that post-operative trans people could marry in their post-operative sex was the New Jersey case M.T. v J.T., (1976). Here the court expressly considered the English Corbett v. Corbett decision, but rejected its reasoning.

In Littleton v. Prange, (1999),[7] Christie Lee Littleton, a post-operative trans woman, argued to the Texas 4th Court of Appeals that her marriage to her genetically male husband (deceased) was legally binding and hence she was entitled to his estate. The court decided that plaintiff's sex is equal to her chromosomes, which were XY (male). The court subsequently invalidated her revision to her birth certificate, as well as her Kentucky marriage license, ruling "We hold, as a matter of law, that Christie Littleton is a male. As a male, Christie cannot be married to another male. Her marriage to Jonathon was invalid, and she cannot bring a cause of action as his surviving spouse." She appealed to SCOTUS but it denied certiorari in 2000.[4]

The Kansas Appellate Court ruling in In re Estate of Gardiner (2001)[8] considered and rejected Littleton, preferring M.T. v. J.T. instead. In this case, the Kansas Appellate Court concluded that "[A] trial court must consider and decide whether an individual was male or female at the time the individual's marriage license was issued and the individual was married, not simply what the individual's chromosomes were or were not at the moment of birth. The court may use chromosome makeup as one factor, but not the exclusive factor, in arriving at a decision. Aside from chromosomes, we adopt the criteria set forth by Professor Greenberg. On remand, the trial court is directed to consider factors in addition to chromosome makeup, including: gonadal sex, internal morphologic sex, external morphologic sex, hormonal sex, phenotypic sex, assigned sex and gender of rearing, and sexual identity." In 2002, the Kansas Supreme Court reversed the Appellate court decision in part, following Littleton.[9]

The custody case of Michael Kantaras made national news.[10] Kantaras met another woman and filed for divorce in 1998, requesting primary custody of the children. Though he won that case in 2002, it was reversed on appeal in 2004 by the Florida Second District Court of Appeal,[11] upholding Forsythe's claim that the marriage was null and void because her ex-husband was still a woman and same-sex marriages were illegal in Florida.[12] Review was denied by the Florida Supreme Court.[13]

In re Jose Mauricio LOVO-Lara (2005),[14] the Board of Immigration Appeals ruled that for purposes of an immigration visa, "A marriage between a postoperative transsexual and a person of the opposite sex may be the basis for benefits under ..., where the State in which the marriage occurred recognizes the change in sex of the postoperative transsexual and considers the marriage a valid heterosexual marriage."[14]

In Fields v. Smith (2006), three transgender women filed a lawsuit against this state of Wisconsin for passing a law banning hormone treatment or sex reassignment surgery for inmates. The courts of appeal struck down the law issuing that transgender people have a right to medical access in prison.[15]

Parental rights

There is little consistency across courts in the treatment of transgender parent in child custody and visitation cases. In some cases, a parent's transgender status is not weighed in a court decision; in others, rulings are made on the basis of a transgender person being presumed to be an inherently unfit parent.

Courts are generally allowed to base custody or visitation rulings only on factors that directly affect the best interests of the child. According to this principle, if a transgender parent's gender identity cannot be shown to hurt the child, contact should not be limited, and other custody and visitation orders should not be changed for this reason. Many courts have upheld this principle and have treated transgender custody cases like any other child custody determination—by focusing on standard factors such as parental skills. In Mayfield v. Mayfield, for instance, the court upheld a transgender parent's shared parenting plan because there was no evidence in the record that the parent would not be a "fit, loving and capable parent."[16]

Other times, courts claiming to consider a child's interests have ruled against the transgender parent, leading to the parent losing access to their children on the basis of their gender identity. For example, in Cisek v. Cisek, the court terminated a transgender parent's visitation rights, holding that there was a risk of both mental and "social harm" to the children. The court asked whether the parent's sex change was "simply an indulgence of some fantasy". An Ohio court imposed an indefinite moratorium on visitation based on the court's belief that it would be emotionally confusing for the children to see "their father as a woman".[17]

Reproductive rights

Transgender people who haven't undergone complete sex reassignment surgery are still able to procreate. However, many U.S. jurisdictions require surgery in order to change the trans person's legal sex. This has been criticized as forced sterilization.[18] Some trans people wish to retain their ability to procreate. Others do not medically require hysterectomy, phalloplasty, metoidioplasty, penectomy, orchiectomy, or vaginoplasty to treat their gender dysphoria. In these cases, surgery is considered medically unnecessary and, for that reason, medically unethical. Additionally, surgery is generally the final series of medical procedures in a complete sex transition, and is financially prohibitive for many people.[19]

There is also advocacy for transgender people to have a legal right to access assisted reproduction technology services and preservation of reproductive tissue prior to having surgery that would render them infertile. This would include cryopreservation of semen in a sperm bank in the case of trans women and oocytes or ovum for trans men. For such individuals, access to surrogacy and in-vitro fertilization services is necessary to have children.[20]

Identity documents

Identity documents are a major area of legal concern for transgender people. Different procedures and requirements for legal name changes and gender marker changes on birth certificates, drivers licenses, social security identification and passports exist and can be inconsistent. Many states require sex reassignment surgery to change their name and gender marker. Also, documents which do not match each other can present difficulties in conducting personal affairs - particularly those which require multiple, matching forms of identification. Furthermore, having documents which do not match a person's gender presentation has been reported to lead to harassment and discrimination.[21][22]

Name change

Transgender people often seek legal recognition for a name change during a gender transition. Laws regarding name changes vary state-by-state. In some states, transgender people can change their name, provided that the change does not perpetrate fraud or enable criminal intent. In other states, the process requires a court order or statute and can be more difficult. An applicant may be required to post legal notices in newspapers to announce the name change - rules that have been criticized on grounds of privacy rights and potentially endangering transgender people to targeted hate crimes.[23] Some courts require medical or psychiatric documentation to justify a name change, despite having no similar requirement for individuals changing names for reasons other than gender transitioning.[24]

Birth certificates

- Some Texas officials have refused to amend the sex on birth certificates to reflect a sex change after the ruling Littleton v. Prange; however, a judge can order an amendment.

- From May 2013 to March 2017 Missouri allowed, through court order via CASE 13AR-CV00240, a quiet workaround of Mo. Ann. Stat. § 193.215(9). The workaround from the original petitioning case has been reversed by mandate of the several courts and Missouri now requires sexual reassignment surgery to change gender.

- In 2020, Idaho passed legislation prohibiting the changing of sex designations on birth certificates.[25] In April 2020 a judicial ruling sated the law was unenforcable.[26][27]

U.S. states make their own laws about birth certificates, and state courts have issued varied rulings about transgender people.[28][29]

Most states permit the name and sex to be changed on a birth certificate, either by amending the existing birth certificate or by issuing a new one, although some require medical proof of sex reassignment surgery to do so. These include:

- Texas, by opinion of the local clerk's office, will make a court-ordered change of sex.

- New York State and New York City both passed legislation in 2014 to ease the process for changing sex on the birth certificate, eliminating the requirement for proof of surgery.[30]

- Nevada eliminated the surgery requirement in November 2016. It requires an affidavit from the person making the change and an affidavit who can attest that the information is accurate.[31]

- Colorado (February 2019) and New Mexico (November 2019) eliminated the surgery requirement and made the gender marker "X" available.[32][33][34]

- Kansas began allowing changes to the gender marker in June 2019. The person must sign an affidavit. If they do not already have documentation (driver's license or passport) with their preferred gender marker, they must bring a letter from a doctor or psychotherapist affirming their gender, but they do not need proof of surgery.[35] Regulations were set up under a signed executive order for the Kansas Department of Health by the Governor of Kansas.

- Virginia removed the requirement for surgery to change the gender marker in September 2020.[36]

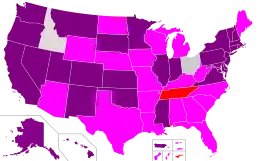

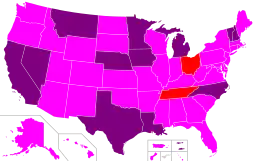

Only one state — Tennessee as of December 2020[37] [38] — will not change the sex on a birth certificate at all, under any circumstances. In December 2020, a federal judge invalidated an unconstitutional law banning sex changes on an individual's birth certificate within Ohio.[39]

Cases

The first case to consider legal gender change in the U.S. was Mtr. of Anonymous v. Weiner (1966), in which a post-operative transgender woman wished to change of her name and sex on her birth certificate in New York City. The New York City Health Department denied the request. She took the case to court, but the court ruled that the New York City Health Code didn't permit the request, which only permitted a change of sex on the birth certificate if an error was made recording it at birth.[40][41]

The decision of the court in Weiner was again affirmed in Mtr. of Hartin v. Dir. of Bur. of Recs. (1973) and Anonymous v. Mellon (1977). Despite this, there can be noted as time progressed an increasing support expressed in judgments by New York courts for permitting changes in birth certificates, even though they still held to do so would require legislative action. Classification of characteristic sex is a public health matter in New York; and New York City has its own health department which operates separately and autonomously from the New York State health department.

An important case in Connecticut was Darnell v. Lloyd (1975),[42] where the court found that substantial state interest must be demonstrated to justify refusing to grant a change in sex recorded on a birth certificate.[43]

In K. v. Health Division (1977),[44] the Oregon Supreme Court rejected an application for a change of name or sex on the birth certificate of a post-operative transgender man, on the grounds that there was no legislative authority for such a change to be made.

Drivers' licenses

All U.S. states allow the gender marker to be changed on a driver's license,[45] although the requirements for doing so vary by state. Often, the requirements for changing one's driver's license are less stringent than those for changing the marker on the birth certificate. For example, the state of Massachusetts requires sex reassignment surgery for a birth certificate change,[46] but only a form including a sworn statement from a physician that the applicant is in fact the new gender to correct the sex designation on a driver's license.[47] The state of Virginia has policies similar to those of Massachusetts, requiring SRS for a birth certificate change, but not for a driver's license change.[48][49]

Sometimes, the states' requirements and laws conflict with and are dependent on each other; for example, a transgender woman who was born in Ohio but living in Kentucky will be unable to have the gender marker changed on her Kentucky driver's license. This is due to the fact that Kentucky requires an amended birth certificate reflecting person's accurate gender, but the state of Tennessee does not change gender markers on birth certificates.[50]

In addition, a number of states and city jurisdictions have passed legislation to allow a third gender marker on official identification documents (see below).

Cases

In May 2015, six Michigan transgender people filed Love v. Johnson in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan, challenging the state's policy requiring the information on a person's driver's license match the information on their birth certificate.[51][52] This policy requires transgender people to change the information on their birth certificates in order to change their driver's licenses, which at the time of filing was not possible in Tennessee, Nebraska and Ohio, where three of the plaintiffs were born, and requires a court order in South Carolina, where a fourth was born. The remaining two residents were born in Michigan, and would be required to undergo surgery to change their birth certificates.[51] The plaintiffs in the case are represented by the American Civil Liberties Union.[51][52]

In November 2015, Judge Nancy Edmunds denied the State of Michigan's motion to dismiss the case.[51]

Passports

The State Department determines what identifying biographical information is placed on passports. On June 10, 2010, the policy on gender changes was amended to allow permanent gender marker changes to be made with the statement of a physician that "the applicant has had appropriate clinical treatment for gender transition to the new gender."[53] The previous policy required a statement from a surgeon that gender reassignment surgery was completed.[54]

Persons not born in the United States

Persons not born in the United States and who hold status in the United States can change the gender marker on their USCIS-issued Certificate of Naturalization, Certificate of Citizenship, Permanent Resident Card, and their State Department-issued Consular Report of Birth Abroad; these serve as foundational identity documents that may be substituted for birth certificates.[55][56]

Other options include obtaining a state court order affirming the change of legal gender as a linking document, such as California's Order Recognizing Change of Gender.[57]

Third gender option

As of 2017, the U.S. federal government does not recognize a third gender option on passports or other national identity documents, though other countries including Australia, New Zealand, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Germany, Malta, and Canada have begun recognizing this.[58][59][60][61][62] Third genders have traditionally been acknowledged in a number of Native American cultures as "two spirit" people, in traditional Hawaiian culture as the māhū, and as the fa'afafine in American Samoa.[63][64][65][66] Similarly, immigrants from traditional cultures that acknowledge a third gender would benefit from such a reform, including the muxe gender in southern Mexico and the hijra of south Asian cultures.[67][68] [69]

On June 10, 2016, an Oregon circuit court ruled that a resident, Jamie Shupe, could obtain a non-binary gender designation. The Transgender Law Center believes this to be "the first ruling of its kind in the U.S."[3]

On September 26, 2016, intersex California resident Sara Kelly Keenan became the second person in the United States to legally change her gender to 'non-binary'. Keenan, who uses she/her pronouns, cited Shupe's case as inspiration for her petition.[70] Keenan later obtained a birth certificate with an intersex sex marker. In press reporting of this decision, it became apparent that Ohio had issued an 'hermaphrodite' sex marker in 2012.[71]

On January 26, 2017, a bill was introduced in the California State Senate that would create a third, nonbinary gender marker on California birth certificates, drivers' licenses, and identity cards. The bill, SB 179, would also remove the requirements for a physician's statement and mandatory court hearing for gender change petitions.[72] This bill was signed into law on October 15, 2017; the non-binary option became available on January 1, 2019.[73]

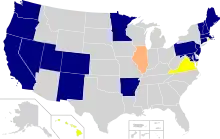

On June 15, 2017, Oregon became the first state in the U.S. to announce it will allow a non-binary "X" gender marker on state IDs and driver's licenses. The law took effect July 1. No doctor's note is required for the change.[74] The following week, Washington D.C. announced that a non-binary "X" gender marker for district-issued ID cards and driver's licenses would very shortly be offered with no medical certification required.[75] The D.C. policy change went into effect on June 27, making the district the first place in the U.S. to offer gender-neutral driver's licenses and ID cards.[76] In June 2018, Maine began issuing yellow stickers to cover part of the ID card with the statement "Gender has been changed to: X - Non-binary".[77] In July 2018, New Jersey enacted legislation to permit people to amend birth and death certificates to reflect their identity as female, male, or "undesignated" without requiring a physician to provide proof of surgery.[78] In October 2018, it was reported that Minnesota would offer an "X" as part of REAL ID.[79] Since November 2018, Colorado has legally provided gender X on driver's license forms and other I.Ds.[80]

Legislation to offer an "X" gender marker for residents' ID cards was introduced in New York state in June 2017[75][81] (and was introduced in New York City in June 2018),[82] and in Massachusetts in May 2018.[83] New York city began offering birth certificates with an "X" gender marker in January 2019.[84]

US jurisdictions with “gender X” driver licenses

- Arkansas (since 2010)[85]

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut[86]

- District of Columbia

- Massachusetts[87][88]

- Maine

- Maryland

- Minnesota

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania[89][90]

- Utah

- Vermont

- Washington State

See the Movement Advancement Project's tracking for up to date information and further sourcing.[91]

Laws offering an "X" gender marker on driver's licenses and state identification cards have also been passed in several US jurisdictions, but have not gone into effect yet namely[92][93][94][95][96] - Rhode Island,[97] Hawaii, Virginia,[98][99] and Illinois (from sometime in 2024 due to delays by government contracts from third parties).

Discrimination

Employment

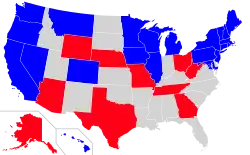

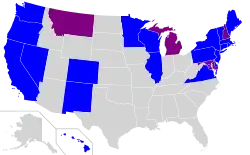

In June 2020 SCOTUS ruled for the first time on a case directly regarding Transgender rights. In the case R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission the Supreme Court held that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act 1964 extends protections to individuals who are transgender in Employment. This is based on discrimination on the grounds of transgender status is a form of discrimination based on sex. Prior to the rulings that Title VII protections covered transgender status, four states (Alaska, Arizona, Minnesota, and Missouri) had not enacted specific protections based on transgender status in any employment, and 22 states had extended protections to public employment only.[100]

Laws

Federal

There is no federal law designating transgender as a protected class, or specifically requiring equal treatment for transgender people. Some versions of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act introduced in the U.S. Congress have included protections against discrimination for transgender people, but as of 2015 no version of ENDA has passed. Whether or not to include such language has been a controversial part of the debate over the bill. In 2016 and again in 2017, Rep. Pete Olson [R-TX] introduced legislation to strictly interpret gender identity according to biology, which would end federal civil rights protection of gender identity. It remains legal at the federal level for parents to subject transgender children to conversion therapy.

On October 4, 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions released a Department of Justice memo stating that Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination based on sex, which he stated "is ordinarily defined to mean biologically male or female," but the law "does not prohibit discrimination based on gender identity per se."[101]

On January 30, 2012, HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan announced new regulations that would require all housing providers that receive HUD funding to prevent housing discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.[102] These regulations went into effect on March 5, 2012.[103]

State and local

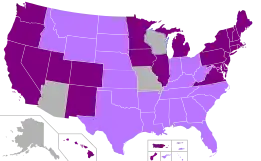

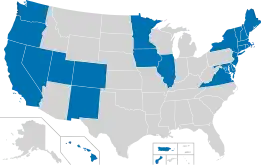

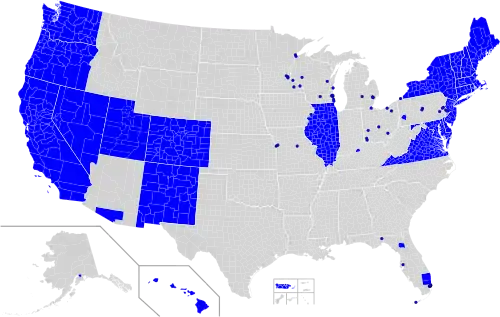

Over 225 jurisdictions including the District of Columbia (as of 2016)[104] and 22 states (as of 2018) feature legislation that prohibit discrimination based on gender identity in either employment, housing, and/or public accommodations. In Anchorage, Alaska, voters chose in April 2018 to keep the existing protections for transgender people.[105] In Massachusetts, a state law prohibited discrimination in public accommodations on the basis of gender identity; in October 2016, anti-transgender activists submitted the minimum number of signatures necessary to the Secretary of the Commonwealth of within Massachusetts to put the law up for repeal on a statewide ballot measure,[106] Massachusetts voters chose on November 6, 2018 to retain the state law, with 67.8% in favor of upholding law, and 32.2% opposed. The Massachusetts Gender Identity Anti-Discrimination Initiative was the first-ever statewide ballot question of its kind in the United States.

Some states and cities have banned conversion therapy for minors.

| State | Date effective | Employment | Housing | Public accommodations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minnesota | 1993[107] | |||

| Rhode Island | Dec 6, 1995 (public accommodation) July 17, 2001 (employment and housing)[108] |

|||

| New Mexico | July 1, 2003 (employment and housing) 2004 (public accommodation) |

|||

| California[109] | 2004 (employment and housing) Oct 9, 2011 (public accommodations) |

|||

| District of Columbia | 2005 (employment and housing) March 8, 2006 (public accommodations) |

|||

| Maine | December 28, 2005 | |||

| Illinois | 2005 (employment and housing) 2006 (public accommodations) |

|||

| Hawaii | July 11, 2005 (housing and public accommodations) May 5, 2011 (employment) |

|||

| Washington | 2006 | |||

| New Jersey | 2006 | |||

| Vermont | 2007 | |||

| Oregon | 2007 | |||

| Iowa | 2007 | |||

| Colorado[110] | 2007 (employment and housing) 2008 (public accommodations) |

|||

| Nevada | 2011 | |||

| Connecticut[111] | October 1, 2011 | |||

| Massachusetts[112] | 2012 (employment and housing) 2016 (public accommodations)[112] |

|||

| Delaware | 2013 | |||

| Maryland | 2014 | |||

| Utah | 2015 | |||

| New York[113] | January 20, 2016 | |||

| New Hampshire[114][115] | July 8, 2018 |

Cases

In 2000, a court ruling in Connecticut determined that conventional sex discrimination laws protected transgender persons. However, in 2011, to clarify and codify this ruling, a separate law was passed defining legal anti-discrimination protections on the basis of gender identity.[116]

On October 16, 1976, SCOTUS rejected plaintiff's appeal in sex discrimination case involving termination from teaching job after sex reassignment surgery from a New Jersey school system.[117]

Carroll v. Talman Fed. Savs. & Loan Association, 604 F.2d 1028, 1032 (7th Cir.) 1979, held that dress codes are permissible. "So long as [dress codes] and some justification in commonly accepted social norms and are reasonably related to the employer's business needs, such regulations are not necessarily violations of Title VII even though the standards prescribed differ somewhat for men and women."[118]

In Ulane v. Eastern Airlines Inc. 742 F.2d 1081 (7th Cir. 1984) Karen Ulane, a pilot who was assigned male at birth, underwent sex reassignment surgery to attain typically female characteristics. The Seventh Circuit denied Title VII sex discrimination protection by narrowly interpreting "sex" discrimination as discrimination "against women" [and denying Ulane's womanhood].[119]

The case of Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins 490 U.S. 228 (1989), expanded the protection of Title VII by prohibiting gender discrimination, which includes sex stereotyping. In that case, a woman who was discriminated against by her employer for being too "masculine" was granted Title VII relief.[120]

Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc. 523 U.S. 75 (1998), found that same-sex sexual harassment is actionable under Title VII.[121]

A gender stereotype is an assumption about how a person should dress which could encompass a significant range of transgender behavior. This potentially significant change in the law was not tested until Smith v. City of Salem 378 F.3d 566, 568 (6th Cir. 2004). Smith, a trans woman, had been employed as a lieutenant in the fire department without incident for seven years. After doctors diagnosed Smith with Gender Identity Disorder ("GID"), she began to experience harassment and retaliation following complaint. She filed Title VII claims of sex discrimination and retaliation, equal protection and due process claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, and state law claims of invasion of privacy and civil conspiracy. On appeal, the Price Waterhouse precedent was applied at p574: "[i]t follows that employers who discriminate against men because they do wear dresses and makeup, or otherwise act femininely, are also engaging in sex discrimination, because the discrimination would not occur but for the victim's sex."[122] Chow (2005 at p214) comments that the Sixth Circuit's holding and reasoning represents a significant victory for transgender people. By reiterating that discrimination based on both sex and gender expression is forbidden under Title VII, the court steers transgender jurisprudence in a more expansive direction. But dress codes, which frequently have separate rules based solely on gender, continue. Carroll v. Talman Fed. Savs. & Loan Association, 604 F.2d 1028, 1032 (7th Cir.) 1979, has not been overruled.

Harrah's implemented a policy named "Personal Best", in which it dictated a general dress code for its male and female employees. Females were required to wear makeup, and there were similar rules for males. One female employee, Darlene Jesperson, objected and sued under Title VII. In Jespersen v. Harrah's Operating Co., No. 03-15045 (9th Cir. April 14, 2006), plaintiff conceded that dress codes could be legitimate but that certain aspects could nevertheless be demeaning; plaintiff also cited Price Waterhouse. The Ninth Circuit disagreed, upholding the practice of business-related gender-specific dress codes. When such a dress code is in force, an employee amid transition could find it impossible to obey the rules.

In Glenn v. Brumby, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals held that the Equal Protection Clause prevented the state of Georgia from discriminating against an employee for being transgender.[123][124]

In education

The Obama administration took the position that Title IX's prohibition on discrimination on the basis of "sex" encompasses discrimination on the basis of gender identity and gender expression. In 2016, the Fourth Circuit became the first[125] Court of Appeals to agree with the administration on the scope of Title IX as applied to transgender students, in the case of Virginia high school student Gavin Grimm (G.G. v. Gloucester County School Board).[126] The validity of the executive's position is being tested further in the federal courts. In 2017 the ACLU, representing Grimm, stated that they had stopped Grimm's "request for an immediate halt to the Gloucester County School Board's policy prohibiting him and other transgender students from using the common restrooms at school" but were "moving forward with his claim for damages and his demand to end the anti-trans policy permanently."[127] Judge Allen of the U.S. District Court of the Eastern District of Virginia, in May 2018, ruled that Grimm's discrimination claim was valid based upon Title IX and the U.S. Constitution's equal protection clause.[128][129]

In 2014, Maryland Senate passed a bill that "bans discrimination based on sexual orientation and sexual identity but includes an exemption for religious organizations, private clubs and educational institutions.[130]

In 2016, guidance was issued by the Departments of Justice and Education stating that schools which receive federal money must treat a student's gender identity as their sex (for example, in regard to bathrooms).[131] However, this policy was revoked in 2017.[131]

Restroom access

An area of legal concern for transgender people is access to restrooms which are segregated by gender. Transgender people have, in the past, been asked for legal identification while entering or using a gendered restroom.[132][133][134] Recent legislation has moved in contradictory directions. On one hand, non-discrimination laws have included restrooms as public accommodations, indicating a right to use gendered facilities which conform with a person's gender identity.[135] On the other, some efforts have been made to insist that individuals use restrooms that match their biological sex, regardless of an individual's gender identity or expression.[136]

Comprehensive legislation

Numerous jurisdictions and states have passed or considered so-called "bathroom bills" which restrict the use of bathrooms by transgender people, forcing them to choose facilities in accordance with their biological sex. This includes Florida, Arizona, Kentucky and Texas.[137][138][139][140]

On March 23, 2016, North Carolina passed a comprehensive bathroom restriction bill (the Public Facilities Privacy & Security Act, also known as "HB2"), overriding a prior municipal Charlotte non-discrimination ordinance on the same subject.[141] It was quickly signed into law by Gov. Pat McCrory, but on March 30, 2017, following national controversy, the part of the law related to bathrooms was repealed.[142] According to the ACLU, the partial repeal still allowed discrimination against transgender persons.[143]

In April 2016, objecting to the "bathroom predator myth," a coalition of over 200 U.S. organizations for sexual assault and domestic violence survivors noted that, while “over 200 municipalities and 18 states" had legal protections for transgender people, none of these places had tied an increase in sexual violence to these nondiscrimination laws.[144]

In September 2016, California governor Jerry Brown signed a bill requiring all single-occupancy bathrooms to be gender-neutral, effective since March 1, 2017.[145] California is the first U.S. state to adopt such legislation.[146] Vermont, New Mexico and Illinois have since followed suit in 2019.[147]

Schools

In Doe v. Regional School Unit, the Maine Supreme Court held that a transgender girl had a right to use the women's bathroom at school because her psychological well-being and educational success depended on her transition. The school, in denying her access, had "treated [her] differently from other students solely because of her status as a transgender girl." The court determined that this was a form of discrimination.[148]

In Mathis v. Fountain-Fort Carson School District 8 (2013), Colorado's Division of Civil Rights found that denying a transgender girl access to the women's restroom at school was discrimination. They reasoned, "By not permitting the [student] to use the restroom with which she identifies, as non-transgender students are permitted to do, the [school] treated the [student] less favorably than other students seeking the same service." Furthermore, the court rejected the school's defense—that the discriminatory policy was implemented to protect the transgender student from harassment—and observed that transgender students are in fact safest when a school does not single them out as different. Based on this finding, it is no longer acceptable to institute different kinds of bathroom rules for transgender and cisgender people.[148]

In May 2016, guidance was issued by the United States Department of Justice and the United States Department of Education stating that schools which receive federal money must treat a student's gender identity as their sex (for example, in regard to bathrooms).[131] However, this policy was revoked in 2017.[131]

In October 2016, SCOTUS agreed to take on the case of whether a transgender boy, Gavin Grimm, could use the boys' bathroom in his Virginia high school. Grimm was assigned female at birth but is a transgender male. For a while, he was permitted access to the boys' bathroom but was later denied access after a new policy was adopted by the local school board. The ACLU took on the case, stating that girls objected when he tried to use the girls' bathroom in accordance with the new policy and that he was humiliated when the school directed him to use a private bathroom, unlike other boys. After challenging the policy, he won his case in the Court of Appeals in 2015 in a tie vote.[149][150] This marked the first ruling by an appeals court to find that transgender students are protected under federal laws that ban sex-based discrimination.[151] However, later in 2016 the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to put that ruling on hold.[152] Then in 2017 the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the decision of the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and refused to hear the case.[153] Later in 2017, it was announced that the 4th Circuit would send the case back to the district court for the judge to determine whether the case was moot because Grimm graduated.[154] The District Court found the case was not moot, and ruled in favor of Grimm, which was later upheld by the Fourth Circuit on appeal in August 2020, using the Supreme Court's recent decision in Bostock v. Clayton County as a basis for their decision.[155]

A similar case had occurred in the public schools of Dallas, Oregon, which had allowed transgender students to use the restrooms and locker rooms of the school based on their gender identity on the basis of the 2016 federal policy. Parents of other students had sued to have the policy overturned, but the policy was upheld at both the United States District Court for the District of Oregon and the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The Supreme Court denied to hear the challenge to the Ninth Circuit in November 2020, leaving that decision in place.[156]

Workplace

Rights to restrooms that match one's gender identity have also been recognized in the workplace and are actively being asserted in public accommodations. In Iowa, for example, discrimination in public accommodations on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity has been prohibited by law since 2007 through the Iowa Civil Rights Act.[148]

In Cruzan v. Special School District #1, decided in 2002, a Minnesota federal appeals court ruled that it isn't the job of the transgender person to accommodate the concerns of cisgender people who express discomfort with sharing a facility with a transgender person. Employers need to offer an alternative to the complaining employee in these situations, such as an individual restroom.[148]

Hate crimes legislation

Federal hate crimes legislation include limited protections for gender identity. The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009 criminalized "willfully causing bodily injury (or attempting to do so with fire, firearm, or other dangerous weapon)" on the basis of an "actual or perceived" identity. However, protections for hate crimes motivated on the basis of a victim's gender identity or sexual orientation is limited to "crime affect[ing] interstate or foreign commerce or occur[ring] within federal special maritime and territorial jurisdiction." This limitation only applies to gender identity and sexual orientation, and not to race, color, religion or national origin.[158] Therefore, hate crimes which occur outside these jurisdictions are not protected by federal law.

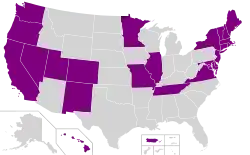

22 states plus Washington D.C. have hate crimes legislation which include gender identity or expression as a protected group. They are Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Missouri, Minnesota, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Rhode Island, Washington, Oregon, California, Hawaii, Maine, Tennessee, Puerto Rico, Utah, Virginia[159] and New York. The District of Columbia also has a trans-inclusive hate crimes law. Twenty-seven states have hate-crimes legislation which exclude transgender people. Six states have no hate-crimes legislation at all.[160]

Numerous municipalities have passed hate-crime legislation, some of which include transgender people. However Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee recently passed laws which ban municipalities from enacting such protections for sexual orientation, gender identity or expression.[161][162]

Healthcare

Transgender people confront two major legal issues within the healthcare system: access to health care for gender transitioning and discrimination by health care workers.

In 2020, at least seven states are considering bills to prevent transgender children from accessing healthcare related to gender transition: South Dakota, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Missouri, South Carolina, and Texas. South Dakota's bill would make it a felony for healthcare providers to provide this care, and it includes an exception for to allow them to perform medically necessary surgeries on intersex children.[163][164]

Even though there is medical consensus that hormone therapy and sex reassignment surgery (SRS) are medically necessary for many transgender people, the kinds of health care associated with gender transition are sometimes misunderstood as cosmetic, experimental or simply unnecessary. This has led to public and private insurance companies denying coverage for such treatment.[165] Courts have repeatedly ruled that these treatments may be medically necessary and have recognized gender dysphoria as a legitimate medical condition constituting a "serious medical need."[166]

The idea that transition-related care is cosmetic or experimental has been ruled as discriminatory and out of touch with current medical thinking. The AMA and WPATH have specifically rejected these arguments, and courts have affirmed their conclusion.[167][168] In a case brought by Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders (GLAD), O'Donnabhain v. Commissioner, for instance, the Internal Revenue Service lost its claim that such treatments were cosmetic and experimental when a transgender woman deducted her SRS procedures as a medical expense. Courts have also found that psychotherapy alone is insufficient treatment for gender dysphoria, and that for some people, SRS may be the only effective treatment.[166]

Transgender people also sometimes experience discrimination by healthcare professionals, who have refused to treat them for conditions both related and unrelated to their gender identity.[169][170][171] A 2017 report by the Center for American Progress found 29 percent of transgender people reporting they were denied care by a medical provider in the preceding year due to their gender identity or sexual orientation. The same study found that 21 percent of trans people reported medical providers used abusive or harsh language when they sought care.[172]

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 prohibits sex discrimination in federally funded health care facilities, and in 2012 the federal Department of Health and Human Services clarified that this includes discrimination based on transgender status though a 2016 injunction prevented the antidiscriminiation protections from going into effect. The relevant anti-discrimination part of ACA is Section 1557. A 2016 ruling stated that discrimination based on gender identity is forbidden by the ACA.[173] The ACA also forbids insurance providers from refusing to cover a person based on a pre-existing condition, including being transgender. A federal judge in Texas in 2016 issued a nationwide injunction stopping the ACA's transgender antidiscrimination protections from taking effect.[174] Complaints sent to the Department of Health and Human Services indicate medical providers still frequently deny care to transgender people on the basis of their gender identity.[174] Protections are provided in some jurisdictions that have laws prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex, gender identity or gender expression in public accommodations - and under medical malpractice and misconduct law.[175]

Transgender people have the right to medical privacy. According to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), medical providers and insurance companies are prohibited from disclosing any personal medical information including a person’s transgender status.[176] HIPAA also allows transgender people to access and receive a copy of their medical records from health care facilities.[176]

It can be difficult for transgender people to find insurance coverage for their medical needs.[177] The ban on Medicare coverage for gender reassignment surgery was repealed by the US Department of Health and Human Services in 2014. Insurance companies, however, still hold the authority to decide whether the procedures are a medical necessity.[177] Thus, insurance companies can decide whether they will provide Medicare coverage for the surgeries.[177]

Under federal tax laws, the Internal Revenue Code, section 213, defines the purpose of “medical care” as “for the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease, or for the purpose of affecting any structure or function of the body.”[178] Only cosmetic surgeries promoting the physical or mental health of an individual can qualify for medical deductions. Transgender people have used the diagnosis of gender dysphoria to qualify for deductible health care.[178]

The lack of knowledge and education related to transgender health is an obstacle transgender people face.[179] A 2011 study published in JAMA reported that medical students cover up to "only five hours" of LGBT related content.[180] A different study done by Lamba Legal in 2010 stated that 89.4% of transgender people felt that there aren’t enough medical providers that are “adequately trained” for their needs.[181] This lack of medical training makes it harder for transgender people to find suitable and proper healthcare.[179]

Prisoners' rights

In September 2011, a California state court denied the request of a California inmate, Lyralisa Stevens, for sex reassignment surgery at the state's expense.[182]

On January 17, 2014, in Kosilek v. Spencer a three-judge panel of the First Circuit Court of Appeals ordered the Massachusetts Department of Corrections to provide Michelle Kosilek, a Massachusetts inmate, with sex reassignment surgery. It said denying the surgery violated Kosilek's Eighth Amendment rights, which included "receiving medically necessary treatment ... even if that treatment strikes some as odd or unorthodox".[183]

On April 3, 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice intervened in a federal lawsuit filed in Georgia to argue that denying hormone treatment for transgender inmates violates their rights. It contended that the state's policy that only allows for continuing treatments begun before incarceration was insufficient and that inmate treatment needs to be based on ongoing assessments.[184] The case was brought by Ashley Diamond, an inmate who had used hormone treatment for seventeen years before entering the Georgia prison system.[185]

On May 11, 2018, the US Bureau of Prisons announced that prison guidelines issued by the Obama Administration in January 2017 to allow transgender prisoners to be transferred to prisons housing inmates of the gender which they identify with had been rescinded and that assigned sex at birth would once again determine where transgender prisoners are jailed.[186]

Immigration

In 2000, the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals concluded that "gay men with female sexual identities [sic] in Mexico constitute a 'particular social group'" that was persecuted and was entitled to asylum in the US (Hernandez-Montiel v. INS).[187][188] Since then, several cases have reinforced and clarified the decision.[189] Morales v. Gonzales (2007) is the only published decision in asylum law that uses "male-to-female transsexual" instead of "gay man with female sexual identity".[189] An immigration judge stated that, under Hernandez-Montiel, Morales would have been eligible for asylum (if not for her criminal conviction).[190]

Critics have argued that allowing transgender people to apply for asylum "would invite a flood of people who could claim a 'well-founded fear' of persecution".[188] Precise numbers are unknown, but Immigration Equality, a nonprofit for LGBT immigrants, estimates hundreds of cases.[188]

The United States has no process for accepting visa requests for third gender citizens from other countries. In 2015, trans HIV activist Amruta Alpesh Soni's request for a visa was delayed because her gender is listed as "T" (for transgender) on her Indian passport. In order to receive a visa, the State Department requires the gender identification on the visa to match the gender identification on the passport.[191]

Military

Currently, transgender people cannot serve or enlist in the United States military, except if they serve in their birth gender, had been grandfathered in prior to April 12, 2019, or were given a waiver. This is a result of Directive-type Memorandum-19-004, which took effect on April 12, 2019 and is set to expire on March 12, 2020.

History

Discharges for gender transitioning were once commonplace. In one case, a trans person who had had gender-reassignment surgery was discharged from the Air Force Reserve, a decision supported by the Court of Appeals.[192]

Obama administration

In 2015, the Pentagon reviewed its policy regarding transgender service members and announced that its ban would be removed.[193] It announced on June 30, 2016 that, effective immediately, existing servicemembers who came out as transgender would no longer be discharged, denied reenlistment, involuntarily separated, or denied continuation of service simply because of their gender,[194] and that, starting in July 2017, people who already identify as transgender were welcome to join the military so long as they had already adapted to their self-identified gender for at least an 18-month period.[194]

Trump administration

President Donald Trump tweeted on July 26, 2017 that transgender individuals will not be allowed to "serve in any capacity in the U.S. military."[195] Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford pushed back, saying that the Secretary of Defense needed time to review this order. "In the meantime," he said, "we will continue to treat all of our personnel with respect."[196] On August 1, 2017, the Palm Center released a letter signed by 56 retired generals and admirals, opposing the proposed ban on transgender military service members. The letter stated that, if implemented, the ban would "deprive the military of mission-critical talent" and would compel cisgender servicemembers "to choose between reporting their comrades or disobeying policy".[197] To challenge Trump's intended policy, at least four lawsuits were filed (Jane Doe v. Trump, Stone v. Trump, Karnoski v. Trump, and Stockman v. Trump), as well as bipartisan Senate and House bills (S. 1820 and H.R. 4041). On August 25, 2017, Trump signed a presidential memorandum to formalize his request for an implementation plan from the Secretary of Defense and the Secretary of Homeland Security.[198] Several days later, Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis announced that he would set up a panel of experts to provide recommendations and that, meanwhile, currently serving transgender troops would be allowed to remain.[199] After another memorandum in 2018, and a further memorandum in 2019 the procedures regarding serving in the armed forces were finalized.

Biden administration

President Joe Biden overturned the laws the Trump Administration put in place to ban Transgender people from serving in the military 5 days after he took the oath of office on January 25, 2021.[200] Biden goes on to say "It is my conviction as Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces that gender identity should not be a bar to military service. Moreover, there is substantial evidence that allowing transgender individuals to serve in the military does not have any meaningful negative impact on the Armed Forces." Biden executive order will be a step by step process. Biden orders repeal, the orders Donald Trump signed banning transgender people from the military, the Department of Defense to correct the record of anyone dismissed from service due to their gender identity, the Secretary of Defense and the Secretary of Homeland Security to begin the process of allowing transgender service members to serve openly.

Taxes

IRS Publication 502[201] lists medical expenses that are tax-deductible to the extent they 1) exceed 7.5% of the individual's adjusted gross income, and 2) were not paid for by any insurance or other third party. For example, a person with $20,000 gross adjusted income can deduct all medical expenses after the first $1,500 spent. If that person incurred $16,000 in medical expenses during the tax year, then $14,500 is deductible. At higher incomes where the 7.5% floor becomes substantial, the deductible amount is often less than the standard deduction, in which case it is not cost-effective to claim.

IRS Publication 502 includes several deductions that may apply to gender transition treatments, including some operations.[201] The deduction for operations was denied to a trans woman but was restored in tax court.[202] The deductibility of the other items in Publication 502 was never in dispute.

Summary

| Transgender Identity and Transvestism legal | |

| Right to change gender on Birth Certificate | |

| Anti-Discrimination laws in Employment | |

| Anti-Discrimination laws in Housing | |

| Anti-Discrimination laws in Public Accommodations | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in health insurance | |

| LGBT anti-bullying law in schools and colleges | |

| LGBT anti-discrimination law in hospitals | |

| Freedom of Expression | |

| Transgender people allowed to serve openly in the Military | |

| Transvestites allowed in the Military | |

| Intersex people allowed in the Military | |

| Legal recognition of gender diversity beyond male/female binary for Intersex people | |

| Intersex Minors protected from invasive surgical procedures | |

| Transgender health care, such as SRS and Hormone medications decriminalized | |

| Transgender Identity declassified as a mental illness | |

| Intersex sex characteristics declassified as a physical deformity | N/A |

See also

References

- Bendery, Jennifer (July 21, 2014). "Obama Signs Executive Order On LGBT Job Discrimination". Archived from the original on July 16, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2017 – via Huff Post.

- Emanuella Grinberg, CNN (May 13, 2016). "White House issues guidance on transgender bathrooms - CNNPolitics.com". CNN. Archived from the original on May 16, 2016.

- O'Hara, Mary Emily (June 10, 2016). "'Nonbinary' is now a legal gender, Oregon court rules". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- J. Courtney Sullivan (July 16, 2015). "What Marriage Equality Means for Transgender Rights". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- Staff report (April 4, 1959). Bars Marriage Permit; Clerk Rejects Proof of Sex of Christine Jorgensen (subscription required). The New York Times

- "Christine Denied Marriage License". Toledo Blade. April 4, 1959. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- "Case # 04-99-00010-CV". Texas Fourth Court of Appeals. 2000. Archived from the original on May 3, 2010. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- "85030 – In re Estate of Gardiner". Court of Appeals of the State of Kansas. 2000. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- "FAQ About Transgender People and Marriage Law". Archived from the original on October 3, 2016.

- Canedy, Dana (February 18, 2002). "Sex Change Complicates Battle Over Child Custody". The New York Times.

- Kantaras v. Kantaras, 884 So. 2d 155 (Fla. Ct. App. 2004)

- Michael J Kantaras v Linda Kantaras [2003] Case No. 98-5375CA. 511998DR005375xxxWS, 6th Circuit

- Kantaras v. Kantaras, 898 So. 2d 80 (Fla. 2005)

- "In re Jose Mauricio LOVO-Lara, Beneficiary of a visa petition filed by Gia Teresa LOVO-Ciccone, Petitioner" (PDF). Usdoj.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 25, 2009. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- "FindLaw's United States Seventh Circuit case and opinions". Archived from the original on June 7, 2016.

- "FAQ About Transgender Parenting". Lambda Legal. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015.

- Cisek v. Cisek, 80 113, 401 (Court of Appeals July 20, 1982) ("Judgment reversed."). – via http://www.lexisnexis.com (subscription required)

- Tornkvist, Ann (November 2, 2011). "Sweden's shameful transgender sterilization rule". Salon.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- The Right to (Trans) Parent Archived November 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, William & Mary Law School

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 19, 2016. Retrieved August 30, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Introduction and Anand's Story". Lambda Legal. Archived from the original on August 28, 2015.

- "Identity Documents & Privacy". National Center for Transgender Equality. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015.

- "California Governor Signs Bill to Remove Barriers for Transgender People to Change Name and Identity Documents". transgenderlawcenter.org. Archived from the original on June 18, 2015.

- "Name Change Ruling". The New York Times. October 21, 2009. Archived from the original on October 27, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- "Idaho House Passes Bill Banning Trans People from Correcting Gender on Birth Certificates". Lambda Legal. February 27, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- https://www.idahostatejournal.com/news/local/judge-idaho-must-allow-gender-changes-on-birth-certificates/article_5214b7e3-ee33-50d2-8f24-9214defdf6fb.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Idaho's transgender birth certificate ban goes back to court". nbcnews. April 17, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- "FindLaw's Writ - Grossman: When Parentage Turns on Anatomical Sex An Illinois Court Denies a Female-to-Male Transsexual's Claim of Fatherhood". findlaw.com. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011.

- Grenberg, Julie (2006). "The Roads Less Travelled: The Problem with Binary Sex Categories". In Currah, Paisley; Juang, Richard; Minter, Minter (eds.). Transgender Rights. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press. pp. 51–73. ISBN 0-8166-4312-1.

- "Insurers in New York Must Cover Gender Reassignment Surgery, Cuomo Says". Archived from the original on March 17, 2015.

- "Victory: Nevada passes the most progressive birth certificate gender change policy in the nation!". National Center for Transgender Equality. November 21, 2016. Archived from the original on April 7, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- "Sex Changes". June 16, 2014.

- "New Mexico".

- "Kansas". National Center for Transgender Equality. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "LIS > Bill Tracking > HB1041 > 2020 session". lis.virginia.gov. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- "Kansas to allow trans residents to change birth certificates".

- "Changing Birth Certificate Sex Designations: State-By-State Guidelines". Lambda Legal. Archived from the original on June 18, 2014.

- Turkington, Richard C.; Allen, Anita L. (August 2002). Privacy law: cases and materials. West Group. pp. 861–. ISBN 9780314262042. Archived from the original on June 26, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- Markowitz, Stephanie. "CHANGE OF SEX DESIGNATION ON TRANSSEXUALS' BIRTH CERTIFICATES: PUBLIC POLICY AND EQUAL PROTECTION" (PDF). Cardozo Journal of Law & Gender. 14: 705–. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 22, 2012.

- "Diana M. DARNELL v. Douglas LLOYD, Commissioner of Health, State of Connecticut". Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- "Darnell v. Lloyd". Archived from the original on October 3, 2016.

- "Annotations to ORS Chapter 432". Oregon State Legislature. Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- "Driver's License Policies by State". National Center for Transgender Equality. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- "General Laws". Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- "Change of Gender". Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- "Sources of Authority to Amend Sex Designation on Birth Certificates". Lambda Legal. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- "Gender Change Request" (PDF). Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- "Driver's License Policies by State". National Center for Transgender Equality. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- Khalil AlHajal, Judge refuses to dismiss challenge to Michigan policy on transgender drivers Archived December 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, MLive (November 16, 2015).

- ACLU Lawsuit: Michigan ID Policy Exposes Transgender Men and Women to Risk of Harassment, Violence Archived May 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, American Civil Liberties Union (May 21, 2015).

- "8 FAM 403.3 Gender Change". United States Department of State. June 27, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- "8 FAM 1004.1 Passport Amendments". United States Department of State. June 27, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- "Chapter 2 - USCIS-Issued Secure Identity Documents | USCIS". www.uscis.gov. April 15, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- "Passports". National Center for Transgender Equality. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- https://www.courts.ca.gov/25797.htm?rdeLocaleAttr=en

- "Nepal issues first third-gender passport, after Australia and N. Zealand". DailySabah. August 10, 2015. Archived from the original on August 17, 2015.

- Jacinta Nandi. "Germany got it right by offering a third gender option on birth certificates". the Guardian. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016.

- Joanna Plucinska (August 11, 2015). "Nepal Is The Latest Country to Acknowledge A Third Gender on Passports". TIME.com. Archived from the original on August 24, 2015.

- "Malta becomes first European country to recognize gender identity in Constitution". dailykos.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015.

- Busby, Mattha (August 31, 2017). "Canada introduces gender-neutral 'X' option on passports". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "The 'two-spirit' people of indigenous North Americans". the Guardian. Archived from the original on January 28, 2017.

- "The Beautiful Way Hawaiian Culture Embraces A Particular Kind Of Transgender Identity". The Huffington Post. April 28, 2015. Archived from the original on January 30, 2017.

- "Fa'afafines: The Third Gender". theculturetrip.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2015.

- "Society Of Fa'afafine In American Samoa - S.O.F.I.A.S." Facebook. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018.

- "In Mexico, Mixed Genders And 'Muxes'". NPR.org. June 5, 2012. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015.

- Homa Khaleeli. "Hijra: India's third gender claims its place in law". the Guardian. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017.

- "Third Gender". Huffington Post. March 19, 2014. Archived from the original on July 29, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- O'Hara, Mary Emily (September 26, 2016). "Californian Becomes Second US Citizen Granted 'Non-Binary' Gender Status". NBC News. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- O'Hara, Mary Emily (December 29, 2016). "Nation's First Known Intersex Birth Certificate Issued in NYC". Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- "TLC Backs CA Bill to Create New Gender Marker and Ease Process for Gender Change in Court Orders and on State Documents". Transgender Law Center. January 26, 2017. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- "SB-179 Gender identity: female, male, or nonbinary". California Legislative Information. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

- Levin, Sam (June 15, 2017). "'Huge validation': Oregon becomes first state to allow official third gender option". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- Rook, Erin (June 22, 2017). "Washington, DC joins Oregon in offering third gender marker on drivers' licenses". LGBTQ Nation. Archived from the original on October 21, 2017. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- Grinberg, Emanuella (June 27, 2017). "You can now get a gender neutral driver's license in D.C." CNN. Archived from the original on June 28, 2017. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- Bouchard, Kelly (June 11, 2018). "Maine begins putting 'non-binary' on driver's licenses for those not 'F' or 'M'". Press Herald. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- Vagianos, Alanna (July 4, 2018). "New Jersey Gov. Signs Bills Giving Transgender Residents More Rights". Huffington Post. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- Church, Danielle (October 3, 2018). "Minnesota Offers "X" Gender Option on Driver's Licenses". KVRR. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- Fetzer, Mary (January 30, 2018). "Third-gender designation: Does your state recognize it?". Avvo Stories. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- Hajela, Deepti (June 4, 2018). "Proposal Would Add 'X' Category to NYC Birth Certificates". NBC New York. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- Holtzman, Michael (May 14, 2018). "Female, male or 'X': Haddad looks to make 3rd gender option on licenses, IDs". South Coast Today. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- Simko-Bednarski, Evan (January 2, 2019). "New York City birth certificates get gender-neutral option". CNN. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- Herreria, Carla (June 27, 2019). "Hawaii Adds Third Gender Option For State-Issued IDs". HuffPost. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- Wood, Pamela (July 6, 2019). "Maryland to allow a 'nonbinary' gender option on voter registration and driver's licenses". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- Tuohy, Dan (July 10, 2019). "Governor Sununu Vetoes Ten Bills, Rejecting Democrats' Policy Priorities". New Hampshire Public Radio. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- "Civil Rights Law Protects Gay and Transgender Workers, Supreme Court Rules". The New York Times. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- Moreau, Julie (October 5, 2017). "Federal Civil Rights Law Doesn't Protect Transgender Workers, Justice Department Says". NBC News. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- "HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan announces new regulations to ensure equal access to housing for all Americans regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity" (Press release). United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. January 30, 2012. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- "Equal Access to Housing in HUD Programs Regardless of Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity" (PDF). Federal Register. February 3, 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- "Cities and Counties with Non-Discrimination Ordinances that Include Gender Identity". Human Rights Campaign. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013.

- Thiessen, Mark (April 12, 2018). "Anchorage voters are 1st in nation to defeat transgender 'bathroom bill' referendum". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- "Learn More". Freedom for All Massachusetts. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- Preston, Joshua. "Allan Spear and the Minnesota Human Rights Act." Minnesota History 65 (2016): 76-87.

- "Rhode island adopts transgender-inclusive non-discrimination law". transgenderlaw.org. Transgender Law and Policy Institute. July 18, 2001. Archived from the original on December 9, 2002. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- Cal Civ Code sec. 51

- C.R.S. 24-34-402 (2008)

- "Connecticut Becomes 15th State to Ban Discrimination Against Transgender Employees". The National Law Review. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011.

- Ennis, Dawn (July 8, 2016). "Massachusetts governor signs sweeping transgender rights bill". Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- "New York Finalizes Ban On Transgender Discrimination". Archived from the original on December 30, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- "Transgender anti-discrimination bill set to become law in New Hampshire". NBC News. Associated Press. May 3, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- "It's Done: Governor Sununu Signs #TransBillNH!". Freedom New Hampshire. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- Declaratory Ruling on Behalf of John/Jane Doe (Connecticut Human Rights Commission 2000)

- "Supreme Court / Sex Discrimination Case / New Jersey Teacher - Oct 18, 1976 - NBC - TV news: Vanderbilt Television News Archive". Tvnews.vanderbilt.edu. October 18, 1976. Archived from the original on December 30, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- "Ca 79-3151 Carroll v. Talman Federal Savings and Loan Association of Chicago". United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- "Ulane v. Eastern Airlines, Inc., 742 F. 2d 1081 - Court of Appeals, 7th Circuit 1984". United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- "Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins". American Psychological Association. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- Minter, Shannon (2003). "Representing Transsexual Clients: Selected Legal Issues". National Center for Lesbian Rights. Archived from the original on October 30, 2007. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- "SMITH v. CITY OF SALEM OHIO". United States Court of Appeals, Sixth Circuit. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- "VIDEO: Eleventh Circuit upholds victory for transgender employee fired by Georgia Legislature". San Diego Gay & Lesbian News. December 6, 2011. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- Dyana Bagby (December 9, 2011). "Vandy Beth Glenn may soon return to work at Ga. General Assembly". The GA Voice. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- Gov. McCrory files brief to reverse Gloucester transgender restroom policy case Archived May 28, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, WTKR, May 10, 2016

- Fausset, Richard (April 19, 2016). "Appeals Court Favors Transgender Student in Virginia Restroom Case". New York Times. Archived from the original on May 14, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- "Complaint amended in transgender lawsuit". Daily Press. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Hurley, Lawrence. "U.S. court backs transgender student at center of bathroom dispute".

- Freeman, Vernon. "Federal court rules in favor of transgender student Gavin Grimm".

- Kunkle, Fredrick (March 4, 2014). "Maryland Senate Passes Bill Banning Discrimination Against Transgender People". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016.

- "Trump Administration Rescinds Protections For Transgender Students | HuffPost". Huffingtonpost.com. February 22, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- Allison Ash. "Team 10: Transgender man claims he was harassed in department store bathroom". 10News. Archived from the original on August 4, 2015.

- "STUDY: Transgender People Experience Discrimination Trying To Use Bathrooms". ThinkProgress. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015.

- Mitch Kellaway. "Angry Activists Confront Trans Teen in Charlotte Bathroom, As Nondiscrimination Ordinance Fails". Advocate.com. Archived from the original on August 11, 2015.

- "Texas Court Sidelines Houston's Nondiscrimination Ordinance". keranews.org. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015.

- Katy Steinmetz (March 6, 2015). "Transgender Bathroom Laws: Kentucky, Florida Bills to Restrict Access". TIME.com. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015.

- "Arizona Transgender Bathroom Bill Won't Move". The Huffington Post. June 6, 2013. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- Dawn Ennis. "BREAKING: Florida's Trans Bathroom Bill Dies". Advocate.com. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016.

- "Parents Fight Bathroom Bills for Transgender Children". The Texas Observer. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015.

- Mic. "Statistics Show Exactly How Many Times Trans People Have Attacked You in Bathrooms". Mic.

- Dave Phillips, North Carolina Bans Local Anti-Discrimination Policies Archived May 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, March 23, 2016.

- http://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/article141647789.html

- ACLU. "ACLU Opposes HB2 Proposal that Would Continue Discrimination". American Civil Liberties Union. American Civil Liberties Union of North Carolina. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- Borrello, Stevie (April 22, 2016). "Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Groups Debunk 'Bathroom Predator Myth'". ABC News. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- Howe, Jason (September 29, 2016). "Governor Signs California "All-Gender" Restroom Bill". Equality California. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- Megarry, Daniel (October 4, 2016). "California becomes first US state to introduce gender-neutral bathroom law". Gay Times. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- "FAQ: Answers to Some Common Questions about Equal Access to Public Restrooms". Lambda Legal. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015.

- Liptak, Adam (October 28, 2016). "Supreme Court to Rule in Transgender Access Case". NY Times. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2016.

- Robert Barnes; Moriah Balingit (October 28, 2016). "Supreme Court takes up school bathroom rules for transgender students". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 29, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2016.

- "Transgender bathroom legal fight reaches Supreme Court". July 13, 2016 – via Reuters.

- Williams, Pete. "Supreme Court Blocks Transgender Bathroom Ruling". NBC News. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- Grindley, Lucas. "Grimm Case Vacated, Sessions Sets Back Trans Rights at Supreme Court". Advocate.com. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- "Judges send Gavin Grimm case back to lower court". Associated Press. August 2, 2017.

- Davies, Emily (August 26, 2020). "Court rules in favor of transgender student barred from using boys' bathroom". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- Kruzel, John; Coleman, Justine (December 7, 2020). "Supreme Court denies review of school transgender bathroom policy". The Hill. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- Anti-Defamation League, June 2006. Retrieved May 4, 2007;

- "The Matthew Shepard And James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act Of 2009". justice.gov. Archived from the original on August 28, 2015.

- "National Equality Map - Transgender Law Center". transgenderlawcenter.org. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015.

- "Arkansas House Votes In Favor Of LGBT Discrimination". The Huffington Post. February 13, 2015. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- Human Rights Watch (January 20, 2020). "Lawmakers in the US Unleash Barrage of Anti-Transgender Bills". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- Wong, Curtis M. (January 30, 2020). "South Dakota House Approves Bill That Would Jail Doctors For Treating Transgender Youth". HuffPost. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- Great Valley Publishing Company, Inc. "Transgender Patients Discriminated Against for Health Care Services". socialworktoday.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- "FAQ on Access to Transition-Related Care". Lambda Legal. Archived from the original on August 30, 2015.

- "WPATH". wpath.org. Archived from the original on August 14, 2015.