Shiatsu

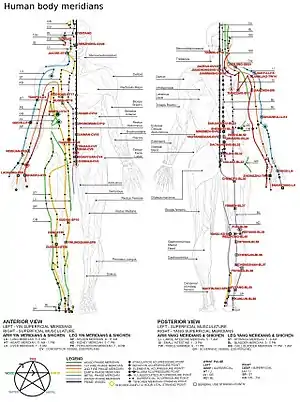

Shiatsu (/ʃiˈæts-, -ˈɑːtsuː/ shee-AT-, -AHT-soo;[1] 指圧) is a form of Japanese bodywork based on concepts in traditional Chinese medicine such as the use of chi meridians. Shiatsu derives from a Japanese massage modality called anma.

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

| Shiatsu | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese name | |||||

| Shinjitai | 指圧 | ||||

| |||||

There is no good evidence that shiatsu is an effective medical treatment.[2]

Description

In the Japanese language, shiatsu means "finger pressure". Shiatsu techniques include massages with fingers, thumbs, feet and palms; acupressure, assisted stretching; and joint manipulation and mobilization.[3] To examine a patient, a shiatsu practitioner uses palpation and, sometimes, pulse diagnosis.

The Japanese Ministry of Health defines shiatsu as "a form of manipulation by thumbs, fingers and palms without the use of instruments, mechanical or otherwise, to apply pressure to the human skin to correct internal malfunctions, promote and maintain health, and treat specific diseases. The techniques used in shiatsu include stretching, holding, and most commonly, leaning body weight into various points along key channels."[4]

Efficacy

There is no evidence that shiatsu is of any benefit in treating cancer or any other disease, though some weak evidence suggests it might help people feel more relaxed.[2] In 2015, the Australian Government's Department of Health published the results of a review of alternative therapies that sought to determine if any were suitable for being covered by health insurance; shiatsu was one of 17 therapies evaluated for which no clear evidence of effectiveness was found.[5]

History

Shiatsu evolved from anma, a Japanese style of massage developed in 1320 by Akashi Kan Ichi.[8][9] Anma was popularised in the seventeenth century by acupuncturist Sugiyama Waichi, and around the same time the first books on the subject, including Fujibayashi Ryohaku's Anma Tebiki ("Manual of Anma"), appeared.[10]

.jpg.webp)

The Fujibayashi school carried anma into the modern age.[11] Prior to the emergence of shiatsu in Japan, masseurs were often nomadic, earning their keep in mobile massage capacities, and paying commissions to their referrers.

Since Sugiyama's time, massage in Japan had been strongly associated with the blind.[12] Sugiyama, blind himself, established a number of medical schools for the blind which taught this practice. During the Tokugawa period, edicts were passed which made the practice of anma solely the preserve of the blind – sighted people were prohibited from practicing the art.[8] As a result, the "blind anma" has become a popular trope in Japanese culture.[13] This has continued into the modern era, with a large proportion of the Japanese blind community continuing to work in the profession.[14]

Abdominal palpation as a Japanese diagnostic technique was developed by Shinsai Ota in the 17th century.[15][16]

During the Occupation of Japan by the Allies after World War II, traditional medicine practices were banned (along with other aspects of traditional Japanese culture) by General MacArthur. The ban prevented a large proportion of Japan's blind community from earning a living. Many Japanese entreated for this ban to be rescinded. Additionally, writer and advocate for blind rights Helen Keller, on being made aware of the prohibition, interceded with the United States government; at her urging, the ban was rescinded.[17]

Tokujiro Namikoshi (1905–2000) founded his shiatsu college in the 1940s and his legacy was the state recognition of shiatsu as an independent method of treatment in Japan. He is often credited with inventing modern shiatsu. However, the term shiatsu was already in use in 1919, when a book called Shiatsu Ho ("finger pressure method") was published by Tamai Tempaku.[18] Also prior to Namikoshi's system, in 1925 the Shiatsu Therapists Association was founded, with the purpose of distancing shiatsu from anma massage.[18][19]

Namikoshi's school taught shiatsu within a framework of western medical science. A student and teacher of Namikoshi's school, Shizuto Masunaga, brought shiatsu back to traditional eastern medicine and philosophic framework. Masunaga grew up in a family of shiatsu practitioners, with his mother having studied with Tamai Tempaku.[18] He founded Zen Shiatsu and the Iokai Shiatsu Center school.[20] Another student of Namikoshi, Hiroshi Nozaki founded the Hiron Shiatsu,[21] a holistic technique of shiatsu that uses intuitive techniques and a spiritual approach to healing which identifies ways how to take responsibility for a healthy and happy life in the practitioner's own hands. It is practiced mainly in Switzerland, France and Italy where its founder opened several schools.[22]

See also

References

- Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- "Shiatsu". Cancer Research UK. 13 December 2018.

- Jarmey, Chris; Mojay, Gabriel (1991). Shiatsu: The Complete Guide. Thorsons. p. 8. ISBN 9780722522431.

Shiatsu therapy is a form of manipulation administered by the thumbs, fingers and palms, without the use of any instrument, mechanical or otherwise, to apply pressure to the human skin

- https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/

- Baggoley C (2015). "Review of the Australian Government Rebate on Natural Therapies for Private Health Insurance" (PDF). Australian Government – Department of Health. Lay summary – Gavura, S. Australian review finds no benefit to 17 natural therapies. Science-Based Medicine. (19 November 2015).

- Ernst E (2013). Healing, Hype or Harm?: A Critical Analysis of Complementary or Alternative Medicine. Andrews UK Limited. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-84540-712-4.

- Hall H (7 June 2016). "The Primo Vascular System: The N-rays of Acupuncture?". Science-Based Medicine.

- Jōya, Moku (1985). Mock Jōya's Things Japanese. The Japan Times. p. 55.

- Fu ren da xue (Beijing, China). Ren lei xue bo wu guan; S.V.D. Research Institute; Society of the Divine Word (1962). Folklore studies. p. 235. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- Kaneko, DoAnn T (2006). Shiatsu Anma Therapy. ISBN 9780977212804.

- Louis Frédéric (2002). Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard University Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- Young, Jacqueline (2007). Complementary Medicine For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 99. ISBN 9780470519684.

- Beresford-Cooke, Carola (2010). Shiatsu Theory and Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780080982472.

- American Foundation for the Blind (1973). "The New outlook for the blind". 67: 178. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Carl Dubitsky (1 May 1997). Bodywork Shiatsu: Bringing the Art of Finger Pressure to the Massage Table. Inner Traditions * Bear & Company. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-89281-526-5. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- Kiiko Matsumoto; Stephen Birch (1988). Hara Diagnosis: Reflections on the Sea. Paradigm Publications. pp. 315–. ISBN 978-0-912111-13-1. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- Beresford-Cooke, Carola (2003). Shiatsu Theory and Practice: A Comprehensive Text for the Student and Professional. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 2. ISBN 9780443070594.

- Anderson, Sandra K. (2008). The Practice of Shiatsu. Mosby Elsevier. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-323-04580-3.

- Stillerman, Elaine (2009). Modalities for Massage and Bodywork. Mosby. pp. 281–300. ISBN 032305255X.

- Jarmey, Chris; Mojay, Gabriel (1991). Shiatsu: The Complete Guide. Thorsons. p. 6. ISBN 9780722522431.

- Hiron Shiatsu

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-01-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)