Solitary confinement

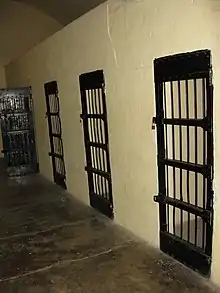

Solitary confinement is a form of imprisonment distinguished by living in single cells with little or no meaningful contact to other inmates, strict measures to control contraband, and the use of additional security measures and equipment. It is specifically designed for disruptive inmates who are security risks to other inmates, the prison staff, or the prison itself. It is mostly employed for violations of discipline, such as violence against others, or as a measure of protection for inmates whose safety is threatened by other inmates.[1]

| Criminology and penology |

|---|

|

According to a 2017 review study, "a robust scientific literature has established the negative psychological effects of solitary confinement", leading to "an emerging consensus among correctional as well as professional, mental health, legal, and human rights organizations to drastically limit the use of solitary confinement."[2] The United Nations considers solitary confinement exceeding 15 days to be torture.[3]

History

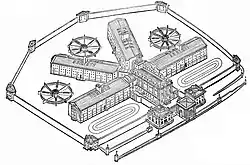

The practice of solitary confinement traces its origins back to the 19th century when Quakers in Pennsylvania used this method as a substitution for public punishments. Research surrounding the possible psychological and physiological effects of solitary confinement dates back to the 1830s. When the new prison discipline of separate confinement was introduced at the Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia in 1829, commentators attributed the high rates of mental breakdown to the system of isolating prisoners in their cells. Charles Dickens, who visited the Philadelphia Penitentiary during his travels to America, described the "slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body".[4] Prison records from the Denmark institute in 1870 to 1920 indicate that staff noticed inmates were exhibiting signs of mental illnesses while in isolation, revealing that the persistent problem has been around for decades.[5]

In the twentieth century, Scandinavian countries such as Denmark have extensively used solitary confinement for prisoners in pretrial detention with the stated goal of preventing them from interfering in the investigation.[6] Norwegian mass murderer Anders Breivik was held in solitary confinement, partly to protect him from other inmates. However, his complaint was partially upheld by the European Court of Human Rights in 2016.[7]

The first comment by the Supreme Court of the United States about solitary confinement's effect on prisoner mental status was made in 1890 (In re Medley 134 U.S. 160).[8][9] In it the court found that the use of solitary confinement produced reduced mental and physical capabilities.[9]

The use of solitary confinement increased greatly during the COVID-19 pandemic in order to avoid spread of the virus in prisons.[10][11][12]

Use

The practice is used when a prisoner is considered dangerous to themselves or to others, is suspected of organizing or being engaged in illegal activities outside of the prison, or, as in the case of a prisoner such as a child molester or a witness, is at a high risk of being harmed by other inmates. The latter example is a form of protective custody. Solitary confinement is also the norm in supermax prisons, where prisoners who are deemed dangerous or of high risk are held.[1]

By country or region

Australia

Solitary confinement is colloquially referred to in Australian English as "the Slot" or "the Pound".

United States

Europe

Solitary confinement as a disciplinary measure for prisoners in Europe was largely reduced or eliminated during the twentieth century.[13]

The European Court of Human Rights has three labels for solitary confinement: complete sensory isolation, total social isolation and relative social isolation.[14]

The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, or CPT, defines solitary confinement as "whenever a prisoner is ordered to be held separately from other prisoners, for example, as a result of court decision, as a disciplinary sanction imposed within the prison system, as a preventive administrative measure or for the protection of the prisoner concerned".[14] The CPT "considers that solitary confinement should only be imposed in exceptional circumstances, as a last resort and for the shortest possible time".[15]

In Italy, a person sentenced to more than one life sentence is required to serve a period of between 6 months to 3 years in solitary confinement during the daytime only.

United Kingdom

In 2004, 40 out of 75,000 inmates held in England and Wales were placed in solitary confinement cells.[16]

In the United Kingdom, the state has a duty to "set the highest standards of care" when it limits the liberties of children.[17] Frances Crook is one of many to believe that incarceration and solitary confinement are the harshest forms of possible punishments and "should only be taken as a last resort".[17] Because children are still mentally developing, incarceration also should not encourage them to commit more violent crimes.[17]

The penal system has been cited as failing to protect juveniles in custody.[17] In the United Kingdom, 29 children died in penal custody between 1990 and 2006: "Some 41% of the children in custody were officially designated as being vulnerable".[17] That is attributed to the fact that isolation and physical restraint are used as the first response to punish them for simple rule infractions.[17] Moreover, Frances Crook argues that these punitive policies not only violate their basic rights but also leave the children mentally unstable and left with illnesses that are often ignored.[17] Overall, the solitary confinement of youth is considered to be counterproductive because the “restrictive environment... and intense regulation of children” aggravates them, instead of addressing the issue of rehabilitation.[17]

Solitary confinement is colloquially referred to in British English as "the block", "The Segregation Unit" or "the cooler".[18][19]

Venezuela

The headquarters for the Bolivarian Intelligence Service (SEBIN) in Plaza Venezuela, Caracas, have an underground detention facility that has been dubbed La Tumba (The Tomb). The facility is located at the place that the underground parking for the Metro Caracas was to be located. The cells are two by three meters that have a cement bed, white walls, security cameras, no windows, and barred doors, with cells aligned next to one another so that there is no interaction between prisoners.[20] Such conditions have caused prisoners to become very ill, but they are denied medical treatment.[21] Bright lights in the cells are kept on so that prisoners lose their sense of time, with the only sounds heard being from the nearby Caracas Metro trains.[22][20][23] Those who visit the prisoners are subjected to strip searches by multiple SEBIN personnel.[22]

Allegations of torture in La Tumba, specifically white torture, are also common, with some prisoners attempting to commit suicide.[20][24][23] Those conditions according to the NGO Justice and Process are intended to make prisoners plead guilty to the crimes that they are accused of.[20]

Effects

There is a scholarly consensus that solitary confinement is seriously harmful, which has led to a growing movement to abolish it.[25]

Psychiatric

Physicians have concluded that for those inmates who enter the prison already diagnosed with a mental illness, the punishment of solitary confinement is extremely dangerous in that the inmates are more susceptible to exacerbating the symptoms.[26] Research indicates that the psychological effects of solitary confinement may encompass "anxiety, depression, anger, cognitive disturbances, perceptual distortions, obsessive thoughts, paranoia, and psychosis."[26] A main issue with isolating prisoners who are known to have mental illnesses is that it prevents the inmates from ever possibly recovering. Instead, many "mentally ill prisoners decompensate in isolation, requiring crisis care or psychiatric hospitalization." It is also noted that if a prisoner is restrained from interacting with the individuals they wish to have contact with they exhibit similar effects.[26]

The lack of human contact, and the sensory deprivation that often go with solitary confinement, can have a severe negative impact on a prisoner's mental state[27] that may lead to certain mental illnesses such as depression, permanent or semi-permanent changes to brain physiology,[28] an existential crisis,[29][30][31][32] and death.[33]

A 2013 systematic review published in Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica concluded that solitary confinement was "associated with negative effects on mental health."[34]

Self-harm

According to a March 2014 article in American Journal of Public Health, "Inmates in jails and prisons attempt to harm themselves in many ways, resulting in outcomes ranging from trivial to fatal."[35]

Self harm was seven times higher among the inmates where seven percent of the jail population was confined in isolation. Fifty-three percent of all acts of self harm took place in jail. "Self-harm" included, but was not limited to, cutting, banging heads, self-amputations of fingers or testicles. These inmates were in bare cells, and were prone to jumping off their beds head first into the floor or even biting through their veins in their wrists.[1] A main issue within the prison system and solitary confinement is the high number of inmates who turn to self-harm.[35]

One study has shown that "inmates ever assigned to solitary confinement were 3.2 times as likely to commit an act of self-harm per 1,000 days at some time during their incarceration as those never assigned to solitary."[35] The study has concluded that there is a direct correlation between inmates who self-harm and inmates that are punished into solitary confinement. Many of the inmates look to self-harm as a way to "avoid the rigors of solitary confinement."[35] Mental health professionals ran a series of tests that ultimately concluded that "self-harm and potentially fatal self-harm associated with solitary confinement was higher independent of mental illness status and age group."[35]

Physical

Solitary confinement has been reported to cause hypertension, headaches and migraines, profuse sweating, dizziness, and heart palpitations. Many inmates also experience extreme weight loss due to digestion complications and abdominal pain. Many of these symptoms are due to the intense anxiety and sensory deprivation. Inmates can also experience neck and back pain and muscle stiffness due to long periods of little to no physical activity. These symptoms often worsen with repeated visits to solitary confinement.[36]

Social

Some sociologists argue that prisons create a unique social environment that do not allow inmates to create strong social ties outside or inside of prison life. Men are more likely to become frustrated, and therefore more mentally unstable when keeping up with family outside of prisons.[37] Extreme forms of solitary confinement and isolation can affect the larger society as a whole. The resocialization of newly released inmates who spent an unreasonable amount of time in solitary confinement and thus suffer from serious mental illnesses is a huge dilemma for society to face.[38] The effects of isolation unfortunately do not stop once the inmate has been released. After release from segregated housing, psychological effects have the ability to sabotage a prisoner's potential to successfully return to the community and adjust back to ‘normal’ life.[39] The inmates are often startled easily, and avoid crowds and public places. They seek out confined small spaces because the public areas overwhelm their sensory stimulation.[39]

Criticism

Ineffectiveness

In 2002, the Commission on Safety and Abuse in America, chaired by John Joseph Gibbons and Nicholas Katzenbach found that: "The increasing use of high-security segregation is counter-productive, often causing violence inside facilities and contributing to recidivism after release."[40]

Solitary confinement has been traditionally used as a behavioral reform of isolating prisoners physically, emotionally and mentally in order to control and change inmate behavior. Recently arrived inmates are more likely to violate prison rules than their inmate counterparts and thus are more likely to be put in solitary confinement. Additionally, individual attributes and environmental factors combine to increase an inmate's likelihood of being put into solitary confinement.[41]

Torture

Solitary confinement is considered to be a form of psychological torture with measurable long-term physiological effects when the period of confinement is longer than a few weeks or is continued indefinitely.[13][42][43][28] In October 2011, UN Special Rapporteur on torture, Juan E. Méndez, told the General Assembly's third committee, which deals with social, humanitarian, and cultural affairs, that the practice could amount to torture:[44] "Considering the severe mental pain or suffering solitary confinement may cause, it can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment when used as a punishment, during pre-trial detention, indefinitely or for a prolonged period, for persons with mental disabilities or juveniles."[44] In November 2014. the United Nations Committee Against Torture stated that full isolation for 22–23 hours a day in super-maximum security prisons is unacceptable.[45] The United Nations have also banned the use of solitary confinement for longer than 15 days.[46]

Political use

Solitary confinement has been used in brainwashing efforts and against political dissidents in countries such as South Africa and Myanmar.[25][47]

In immigration detention centers, reports have surfaced concerning its use against detainees in order to keep those knowledgeable about their rights away from other detainees.[48] In the prison-industrial complex itself, reports of solitary confinement as punishment in work labor prisons have also summoned much criticism.[49] One issue prison reform activists have fought against is the use of Security Housing Units (extreme forms of solitary confinement). They argue that they do not rehabilitate inmates but rather serve only to cause inmates psychological harm.[50] Further reports of placing prisoners into solitary confinement based on sexual orientation, race and religion have been an ongoing but very contentious subject in the last century.[51]

Access to healthcare

Research has shown that the routine features of prison can make huge demands on limited coping resources. After prison many ex-convicts with mental illness do not receive adequate treatment for their mental health issues, because health services turn them away. This is caused by restrictive policies or lack of resources for treating the formerly incarcerated individual.[52] In a study focusing on women and adolescent men, those who had health insurance, received mental health services, or had a job were less likely to return to jail. However, very few of the 1,000 individuals in this study received support from mental health services.[53]

Ethics

Treating mentally ill patients by sentencing them into solitary confinement has captured the attention of human rights experts who conclude that "solitary confinement may amount to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment" that violates rights specifically targeting cruel, inhuman treatment.[26] Health care professionals and organizations recognize the fact that solitary confinement is not ethical, yet the segregating treatment fails to come to a halt.[26] "Experience demonstrates that prisons can operate safely and securely without putting inmates with mental illness in typical conditions of segregation."[26] Despite this and medical professionals' obligations, segregation policies have not changed because mental health clinics believe that "isolation is necessary for security reasons."[26] In fact, many believe that it is ethical for physicians to help those in confinement but that the physicians should also be trying to stop the abuse. If they cannot do so they are expected to undertake public advocacy.[54]

Legality

The legality of solitary confinement has been frequently challenged over the past sixty years as conceptions surrounding the practice have changed. Much of the legal discussion concerning solitary confinement has centered on whether or not it constitutes torture or cruel and unusual punishment. While international law has generally begun to discourage solitary confinement's use in penal institutions,[55] opponents of solitary confinement have been less successful at challenging it within the United States legal system.

The UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and other UN bodies have stated that the solitary confinement (physical and social isolation of 22–24 hours per day for 1 day or more) of young people under age 18, for any duration, constitutes cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment.[56]

The documented psychological effects led one Texas judge in a 2001 suit to rule that "Solitary confinement units are virtual incubators of psychoses—seeding illness in otherwise healthy inmates and exacerbating illness in those already suffering from mental infirmities."[57] In fact, as of 2016, there have been thirty-five U.S. Supreme Court cases petitioning solitary confinement.[58]

International law

Throughout the twentieth century, the United Nations' stance on solitary confinement has become increasingly oppositional. International law has reflected this change, and UN monitoring has led to a major reduction of solitary confinement.[55]

In 1949, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly. Although the Declaration is non-binding, the basic human rights outlined within it have served as the foundation of customary international law.[55] The relevance of the Declaration to solitary confinement is found in Article 5, which states that "No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment."[59] Thus, if solitary confinement is believed to constitute torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, then the country practicing solitary confinement is violating the provisions set by the UDHR.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), effective 1976, reiterates the fifth article of the UDHR; Article 7 of the ICCPR identically states, "No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment."[60] Because the ICCPR is a legally binding agreement, any nation that is signatory to the covenant would be violating international law if it practiced torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.

At the time that the UDHR and ICCPR were adopted, solitary confinement was not yet believed to constitute torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.[55] Its practice, therefore, was not believed to violate international law. This changed, however, after the UN definition of torture was outlined in detail in the 1984 Convention Against Torture (CAT); Article 1.1 of the CAT states that torture is "any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person" for any reason such as obtaining information or punishment, and Article 16 of the same convention prohibits "other acts of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment". Based on these provisions, many members of the UN began to believe that solitary confinement's detrimental psychological effects could, indeed, constitute cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, if not, torture.[55] In the years following the CAT, UN representatives "have publicly decried the use of solitary confinement as a violation of the CAT and ICCPR," as well as the UDHR.[55]

In more recent years, UN representatives have strengthened their efforts to stop solitary confinement from being used worldwide.[55] The urgency with which representatives have undertaken these efforts is largely due to the UN Special Rapporteurs on Torture, Manfred Nowak and Juan Méndez.[55] Nowak and Méndez have both "repeatedly unequivocally stated that prolonged solitary confinement is cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, and may amount to torture".[55] Nowak and Méndez have been especially critical of long-term or prolonged solitary confinement, which they define as lasting fifteen days or more.[55] Their authority and explicit characterization of solitary confinement as cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment has led the UN to include long-term to indefinite solitary confinement in the group of practices that violate the provisions outlined in the UDHR, ICCPR, and CAT. Solitary confinement lasting for a short period of time, however, is allowed under international law when used as a last resort, though Nowak, Mendez, and many other UN representatives believe that the practice should be abolished altogether.[55]

According to a law review article by Elizabeth Vasiliades, America's detention system is far below the basic minimum standards for treatment of prisoners under international law and has caused an international human rights concern: "U.S. solitary confinement practices contravene international treaty law, violate established international norms, and do not represent sound foreign policy."[61]

Opposition and protests

The 2013 California prisoner hunger strike saw approximately 29,000 prisoners protesting conditions.[62] This statewide hunger strike reaching 2/3 of California's prisons began with the organizing of inmates at Pelican Bay State Prison. On 11 July 2011, prisoners at Pelican Bay State Prison began a hunger strike to "protest torturous conditions in the Security Housing Unit (SHU) there..." and to advocate for procedural and policy changes like the termination of the "debriefing process" which forces prisoners "to name themselves or others as gang members as a condition of access to food or release from isolation".[63] Nearly 7,000 inmates throughout the California prison system stood in solidarity with these Pelican State Bay prisoners in 2011 by also refusing their food.[63] Also in solidarity with the 2011 Pelican Bay prisoners on strike is the Bay Area coalition of grassroots organizations known as the Prisoner Hunger Strike Solidarity coalition. This coalition has aided the prisoners in their strike by providing a legal support force for their negotiations with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) and by creating and running a media based platform to raise support and awareness for the strikers and their demands among the general public.[63]

Solitary confinement has served as a site of inspiration for protest-organizing against its use in and outside of prisons and conversely, as a response tactic for prisons to react to the protest-organizing of its prisoners. In March 2014, authorities at the Northwest Detention Center in Washington relegated multiple detainees to solitary confinement units after their participation in protests for the improvement of conditions within the facility and in solidarity with activist organizing against deportation escalations outside of the facility.[64]

Alternatives and reform

Possible alternatives

Scrutiny of super-maximum security prisons and the institutionalization of solitary confinement is accompanied by suggestions for alternative methods. One alternative is to administer medical treatment for disorderly inmates who display signs of mental illness.[65] The Correction Department of New York City implemented plans to transfer mentally ill inmates to an internal facility for further help rather than solitary confinement in 2013.[65] Dora B. Schriro, correction commissioner, said that treatment would help turn a “one size fits all” policy into a program to promote success in jail and the outside world.[65] A second alternative is to deal with long-term inmates by promoting familial and social relationships through the encouragement of visitations which may help boost morale.[66] Carl Kummerlowe believes that familial counseling and support may be useful for inmates nearing the end of a long-term sentence that may otherwise exhibit signs of aggression.[66] This alternative would help inmates cope with extreme long term sentences in prisons such as those harbored in Pelican Bay.[66] A third alternative would involve regular reevaluation and accelerated transition of isolated inmates back to prison population to help curb long-term effects of solitary confinement.[66] These alternative methods suggest a more restorative justice approach to handling high-security offenders.

Recent reform

Many states such as Colorado, Mississippi, and Maine have implemented plans to reduce use of supermax prisons and solitary confinement and have begun to show signs of reform.[65] Joseph Ponte, Corrections Commissioner of Maine, cut supermax prison population by half.[65] Colorado has announced reforms to limit the use of solitary confinement in prisons following a study that showed significant levels of confinement and isolation in prisons.[65] Washington has also showed signs of decreased use of solitary confinement, low segregation of overall prison population, and emphasis on alternative methods.[65]

Women

Studies have shown the effects of solitary confinement to be detrimental to all inmates, but solitary confinement of women has particular consequences for women that may differ from the way it affects men. Rates for women in the United States are roughly comparable to those for men, and about 20% of prisoners are in solitary confinement at some point during their prison career.[67][68]

See also

- Prison#Control units

- Isolation to facilitate abuse

- Prison abolition movement

- Single-celling

- Box (form of torture involving solitary confinement in an overheated room)

References

- Bottos, Shauna. 2007. Profile of Offenders in Administrative Segregation: A Review of the Literature. Research Report No. B-39. Ottawa: Research Branch, Correctional Service of Canada.

- Haney, Craig (3 November 2017). "Restricting the Use of Solitary Confinement". Annual Review of Criminology. 1: 285–310. doi:10.1146/annurev-criminol-032317-092326. ISSN 2572-4568.

- Hart, Alexandra; Cabrera, Kristen (23 January 2020). "Why Some Experts Call Solitary Confinement 'Torture'". Texas Standard. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Dickens, Charles (1842). American Notes. Chapman and Hall.

- Smith, Peter Scharff (August 2008). "'Degenerate Criminals': Mental Health and Psychiatric Studies of Danish Prisoners in Solitary Confinement, 1870–1920". Criminal Justice and Behavior. 35 (8): 1048–1064. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.559.5564. doi:10.1177/0093854808318782.

- Smith, Peter Scharff (2006). "The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates: A Brief History and Review of the Literature". Crime and Justice. 34 (1): 441–528. doi:10.1086/500626. ISSN 0192-3234.

- "Anders Breivik case: How bad is solitary confinement?". BBC News. 20 April 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- "In re Medley/Opinion of the Court - Wikisource, the free online library".

- Arrigo, Bruce A.; Bullock, Jennifer Leslie (December 2008). "The Psychological Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prisoners in Supermax Units". International Journal of Offender Therapy & Comparative Criminology. 52 (6): 622–640. doi:10.1177/0306624X07309720. PMID 18025074.

- Cloud, David H.; Ahalt, Cyrus; Augustine, Dallas; Sears, David; Williams, Brie (6 July 2020). "Medical Isolation and Solitary Confinement: Balancing Health and Humanity in US Jails and Prisons During COVID-19". Journal of General Internal Medicine: 1–5. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05968-y. ISSN 0884-8734.

- "As COVID-19 Spreads In Prisons, Lockdowns Spark Fear Of More Solitary Confinement". NPR.org. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- "16 years old and stuck in solitary confinement 23 hours a day because of coronavirus". CNN. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Gawande, Atul (7 January 2009). "Is long-term solitary confinement torture?". The New Yorker. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- Oslo District Court declaratory judgement for breach of the ECHR art. 3 & 8; Anders Behring Breivik plaintiff (PDF) (Report). 20 April 2016. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- Solitary confinement of prisonersExtract from the 21st General Report of the CPT, published in 2011

- Tapley, Lance (1 November 2010). "The Worst of the Worst: Supermax Torture in America". Boston Review. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- Crook, Frances (September 2006). "Where Is Child Protection in Penal Custody?". Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 16 (3): 137–141. doi:10.1002/cbm.627. PMID 16838387.

- "Army captain was real life 'Cooler King' from The Great Escape". The Daily Telegraph. London. 17 June 2009. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- "Cooler King recalls Great Escape". BBC News. 16 March 2004. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- Vinogradoff, Ludmila (10 February 2015). ""La tumba", siete celdas de tortura en el corazón de Caracas". ABC. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Statement of Santiago A. Canton Executive Director, RFK Partners for Human Rights Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights" (PDF). United States Senate. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Un calabozo macabro". Univision. 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- "Political protesters are left to rot in Venezuela's secretive underground prison". News.com.au. 25 July 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "UNEARTHING THE TOMB: INSIDE VENEZUELA'S SECRET UNDERGROUND TORTURE CHAMBER". Fusion. 2015. Archived from the original on 29 July 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Haney, Craig (2018). "Restricting the Use of Solitary Confinement". Annual Review of Criminology. 1 (1): 285–310. doi:10.1146/annurev-criminol-032317-092326.

- Metzner, Jeffrey L.; Fellner, Jamie (March 2010). "Solitary Confinement and Mental Illness in U.S. Prisons: A Challenge for Medical Ethics". J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 38 (1): 104–108. PMID 20305083. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- Kerness, Bonnie (Fall 1998). "Solitary Confinement Torture In The U.S." The North Coast Xpress. Archived from the original on 28 June 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Grassian, Stuart (January 2006). "Psychiatric effects of solitary confinement" (PDF). Wash. U. J. L. & Pol'y. 22: 325. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- Grassian, Stuart (November 1983). "Psychopathological effects of solitary confinement". American Journal of Psychiatry. 140 (11): 1450–1454. doi:10.1176/ajp.140.11.1450. PMID 6624990.

- Haney, Craig (January 2003). "Mental Health Issues in Long-Term Solitary and "Supermax" Confinement". Crime & Delinquency. 49 (1): 124–156. doi:10.1177/0011128702239239.

- Franklin, Karen. "Segregation Psychosis". Archived from the original on 5 October 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Schwartz, Harold I. (1 June 2005). "Death Row Syndrome and Demoralization: Psychiatric Means to Social Policy Ends". J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 33 (2): 153–155. PMID 15985656. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- "Survivors of Solitary Confinement". Making Contact. Season 12. Episode 22. 3 June 2009. National Radio Project. Retrieved 12 June 2016. Direct link to audio file.

- Walker, J.; et al. (18 November 2013). "Changes in Mental State Associated with Prison Environments: A Systematic Review". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 129 (6): 427–36. doi:10.1111/acps.12221. PMID 24237622.

- Kaba, Fatos; et al. (March 2014). "Solitary Confinement and Risk of Self-Harm Among Jail Inmates". American Journal of Public Health. 104 (3): 442–447. doi:10.2105/ajph.2013.301742. PMC 3953781. PMID 24521238.

- Murphy Corcoran, Mary. "Effects of Solitary Confinement on the Well Being of Prison Inmates". NYU Steinhardt Department of Applied Psychology. NYU Steinhardt. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- Lindquist, Christine H. (September 2000). "Social Integration and Mental Well-Being Among Jail Inmates". Sociological Forum. 15 (3): 431–455. doi:10.1023/A:1007524426382.

- Kupers, Terry A. (August 2008). "What To Do With the Survivors? Coping With the Long-Term Effects of Isolated Confinement". Criminal Justice and Behavior. 35 (8): 1005–1016. doi:10.1177/0093854808318591.

- Goode, Erica (3 August 2015). "Solitary Confinement: Punished for Life". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- John J. Gibbons; Nicholas de B. Katzenbach (8 June 2006). "Confronting Confinement: A Report of The Commission on Safety and Abuse in America's Prisons" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- Adams, Kenneth (1992). "Adjusting to Prison Life". Crime and Justice. 16: 275–359. doi:10.1086/449208.

- A. Vrca; V. Bozikov; Z. Brzović; R. Fuchs; M. Malinar (September 1996). "Visual evoked potentials in relation to factors of imprisonment in detention camps". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 109 (3): 114–117. doi:10.1007/BF01369669. PMID 8956983.. This is the study of 57 Yugoslav POWs referenced in Atul Gawande's 2009 New Yorker article.

- Hresko, Tracy (Spring 2006). "In the Cellars of the Hollow Men". Pace International Law Review.

- Section, United Nations News Service (18 October 2011). "UN News - Solitary confinement should be banned in most cases, UN expert says". UN News Service Section.

- http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CAT/Shared%20Documents/USA/INT_CAT_COC_USA_18893_E.pdf

- Ramin Skibba (22 June 2018). "The hidden damage of solitary confinement". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-062118-065101.

- "Burma's Key Dissidents". The World from PRX. 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Venters, Homer; Dasch-Goldberg, Dana; Rasmussen, Andrew; Keller, Allen S. (May 2009). "Into the Abyss: Mortality and Morbidity Among Detained Immigrants". Human Rights Quarterly. 31 (2): 474–495. doi:10.1353/hrq.0.0074.

- Chang, Tracy F. H.; Thompkins, Douglas E. (2002). "Corporations Go to Prisons: The Expansion of Corporate Power in the Correctional Industry". Labor Studies Journal. 27 (1): 45–69. doi:10.1353/lab.2002.0001.

- Liebling, Alison (1999). "Prison Suicide and Prisoner Coping". Crime and Justice. 26: 283–359. doi:10.1086/449299. JSTOR 1147688.

- Browne, Angela; Cambier, Alissa; Agha, Suzanne (October 2011). "Prisons Within Prisons: The Use of Segregation in the United States". Federal Sentencing Reporter. 24 (1): 46–49. doi:10.1525/fsr.2011.24.1.46. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Primm, Annelle B.; Osher, Fred C.; Gomez, Marisela B. (2005). "Race and Ethnicity, Mental Health Services and Cultural Competence in the Criminal Justice System: Are we Ready to Change?". Community Mental Health Journal. 41 (5): 557–569. doi:10.1007/s10597-005-6361-3. PMID 16142538.

- Freudenberg, Nicholas; et al. (October 2005). "Coming Home From Jail: The Social and Health Consequences of Community Reentry for Women, Male Adolescents, and Their Families and Communities". Am J Public Health. 95 (10): 1725–1736. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.056325. PMC 1449427. PMID 16186451.

- Metzner, Jeffrey L.; Fellner, Jamie (1 March 2010). "Solitary Confinement and Mental Illness in U.S. Prisons: A Challengefor Medical Ethics". The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 38 (1): 104–108. ISSN 1093-6793. PMID 20305083.

- Conley, Anna (April 2013). "Torture in US Jails and Prisons: An Analysis of Solitary Confinement Under International Law". Vienna J. On Int'l Const. Law. 7: 415–453. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ACLU/Human Rights Watch (2012). Growing Up Locked Down: Youth in Solitary Confinement in Jails and Prisons in the United States (PDF). United States of America. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-56432-949-3.

- Ruiz v. Johnson, 154 F.Supp.2d 975 (S.D.Tex.2001)

- "U.S. Supreme Court Cases". Solitary Watch. 11 December 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN.org)

- "OHCHR - International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights". ohchr.org.

- Vasiliades, Elizabeth (2005). "Solitary Confinement and International Human Rights: Why the US Prison System Fails Global Standards" (PDF). Amer. U. Int'l Law Rev. 21: 71–101. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- Miles, Kathleen (9 July 2013). "California Prison Hunger Strike: 30,000 Inmates Refuse Meals". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Cohn, Marjorie (July 2011). "Prisoners Strike Against Torture in California Prisons". National Lawyers Guild Review. 68 (1): 61–62. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Honig, Doug; Lee, Melissa (4 April 2014). "Hunger Strikers Released from Solitary Confinement at New Detention Center". American Civil Liberties Union of Washington State. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Rice, Heather. "Alternatives to Solitary Confinement - National Religious Campaign Against Torture". www.nrcat.org.

- King, Kate; Steiner, Benjamin; Breach, Stephanie R. (March 2008). "Violence in the Supermax: A Self Fulfilling Prophecy". The Prison Journal. 88 (1): 144–68. doi:10.1177/0032885507311000.

- "FAQ". Solitary Watch. 31 January 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- "Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) - Use of Restrictive Housing in U.S. Prisons and Jails, 2011–12". www.bjs.gov. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

Bibliography

- Birckhead, T. R. (2015). Children in isolation: The solitary confinement of youth. Wake Forest Law Review 50(1), 1-80.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Solitary confinement. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Solitary confinement |

- 6×9: A virtual experience of solitary confinement. The Guardian.