Bolivarian Intelligence Service

The Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (Spanish: Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional, SEBIN) is the premier intelligence agency in Venezuela. SEBIN is an internal security force subordinate to the Vice President of Venezuela since 2012 and is dependent on Vice President Delcy Rodríguez.[3] SEBIN has been described as the political police force of the Bolivarian government.[4][5][6]

| Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional SEBIN | |

Seal of the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service | |

Flag of the Bolivarian Intelligence Service | |

| Intelligence agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | June 2, 2010 |

| Preceding Intelligence agency | |

| Headquarters | Plaza Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela[1] |

| Employees | Classified |

| Annual budget | $169 million (2013)[2] |

| Intelligence agency executives | |

| Parent department | Vice President of Venezuela |

History

The Venezuelan intelligence agency has an extensive record of human rights violations,[7] including recent allegations of torture and murder of political opponents.[8][9][10]

Predecessors

The predecessor of SEBIN was established in March 1969 with the name of DISIP, Dirección Nacional de los Servicios de Inteligencia y Prevención ("National Directorate of Intelligence and Prevention Services"), by then-president Rafael Caldera, replacing the Dirección General de Policía (DIGEPOL).

Human Rights Watch wrote in 1993 that DISIP was involved in targeting political dissenters within Venezuela and was involved in abusive tactics.[11] In their 1997 and 1998 reports, Amnesty International also detailed human rights violations by DISIP, including unlawful detention of Venezuelan human rights activists.[12][13]

Bolivarian Revolution

In 1999, President Hugo Chávez began the restructuring of DISIP, with commanders and analysts being selected for their political attributes and rumors of some armed civilian groups gaining credentials from such actions.[14] A retired SEBIN commissioner explained that there began to be "biased and incomplete reports, tailored to the new ears, that began to proliferate and ultimately affects the ability of the institution to process information and know what happens".[14] On December 4, 2009, President Chávez, during a swearing-in ceremony for the high command of the recently created Bolivarian National Police (Policía Nacional Bolivariana), announced the change of name of DISIP, with immediate effect, to Bolivarian Intelligence Service (Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia, or SEBIN).[15]

The restructuring of SEBIN was completed in 2013 with one of its goals to guarantee the "continuity and consolidation of the Bolivarian Revolution in power".[14][16] In the beginning of the 2014–15 Venezuelan protests, SEBIN agents open fire on protesters which resulted in the deaths of two and the dismissal of Brigadier General Manuel Gregorio Bernal Martinez days later.[16]

Under the Nicolas Maduro presidency, a building that was originally intended to be a subway station and offices in Plaza Venezuela was converted into the headquarters for SEBIN.[16][17] Dubbed "La Tumba", or "The Tomb", by Venezuelan officials, political prisoners are allegedly held five stories underground in inhumane conditions at below freezing temperatures and with no ventilation, sanitation, or daylight.[18][19][20] The cells are two by three meters that have a cement bed, security cameras and barred doors, with each cell aligned next to one another so there are no interactions between prisoners.[17] Such conditions have caused prisoners to become very ill though they are denied medical treatment.[20] Denounces of torture in "The Tomb", specifically white torture, are also common, with some prisoners attempting to commit suicide.[17][18][19] Such conditions according to NGO Justice and Process are to force prisoners to plead guilty to crimes they are accused of.[17]

Domestic actions

Media

According to El Nacional, SEBIN had raided facilities of reporters and human rights defenders several times.[21] It was also stated that SEBIN occasionally intimidated reporters by following them in unmarked vehicles where SEBIN personnel would "watch their homes and offices, the public places like bakeries and restaurants, and would send them text messages to their cell phones".[21]

Following the Narcosobrinos incident which saw President Maduro's nephews arrested in the United States for drug trafficking, Associated Press reporter Hannah Dreier, who had been awarded for her reporting on Venezuela,[22] was detained by SEBIN agents in Sabaneta, Barinas. SEBIN agents threatened her during an interrogation, saying they would behead her like ISIL did to James Foley and said that they would let her go for a kiss. Finally, agents said that they wanted to coerce the United States to exchange Maduro's nephews for Dreier, accusing her of being a spy and sabotaging the Venezuelan economy.[23]

Public surveillance

In an El Nuevo Herald, former SEBIN officials and security experts state that the Venezuelan government has allegedly spent millions of dollars to spy on Venezuelans; using Italian and Russian technology to monitor emails, keywords and telephone conversations of its citizens; especially those who use the dominant, state-controlled telecommunications provider CANTV. Acquired information is used to create a "person of interest" for Venezuelan authorities, where only selected individuals could have been fully spied on and where a database had been created to monitor those who publicly disagreed with the Bolivarian Revolution.[24]

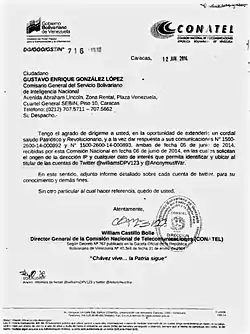

In 2014, multiple Twitter users were arrested and faced prosecution due to the tweets they made.[25] Alfredo Romero, executive director of the Venezuelan Penal Forum (FPV), stated that the arrests of Twitter users in Venezuela was a measure to instill fear among those using social media that were critical against the government.[25] In October 2014, eight Venezuelans were arrested shortly after the death of PSUV official Robert Serra.[26] Though the eight Venezuelans were arrested in October 2014, the Venezuelan government had been monitoring them since June 2014 according to leaked documents, with the state telecommunications agency Conatel providing IP addresses and other details to the Venezuelan intelligence agency SEBIN in order to arrest Twitter users.[26]

Surveillance on Jewish community

In January 2013, 50 documents were leaked by Analisis24 showing that SEBIN had been collecting "private information on prominent Venezuelan Jews, local Jewish organizations and Israeli diplomats in Latin America". Some info that was gathered by SEBIN operations included office photos, home addresses, passport numbers and travel itineraries. The leaked documents were believed to be authentic according to multiple sources which included the Anti-Defamation League, that stated, "It is chilling to read reports that the SEBIN received instructions to carry out clandestine surveillance operations against members of the Jewish community".[27][28]

2004 Venezuela recall protests

In March 2004, Amnesty International stated in a report following 2004 Venezuela recall protests that SEBIN (then DISIP) "allegedly used excessive force to control the situation on a number of occasions".[29]

2014–17 Venezuelan protests

Seven SEBIN members caused the first deaths of the 2014–15 Venezuelan protests on 12 February 2014 after shooting at unarmed, fleeing, protesters several times in violation of protocol, which resulted in the deaths of Bassil Da Costa and Juan Montoya.[30][31] Days later, on February 17, armed SEBIN agents raided the headquarters of Popular Will in Caracas and held individuals who were inside at gunpoint.[32]

Following alleged human rights violations by SEBIN during the protests, U.S. President Barack Obama used powers granted from the Venezuela Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society Act of 2014 and ordered the United States Department of the Treasury to freeze assets and property of the Director General of SEBIN, Gustavo Enrique González López and the former Director General, Manuel Gregorio Bernal Martínez.[33]

International actions

United States

In 2012, Livia Acosta Noguera and at least 10 other SEBIN agents that were allegedly operating under the guise of diplomatic missions left the United States following a controversy involving Acosta.[34] In a Univision documentary, while Acosta was a cultural attaché in Mexico, she allegedly met with Mexican students posing as hackers that were supposedly planning to launch cyberattacks on the White House, the FBI, The Pentagon and several nuclear plants.[35][36][37] After an FBI investigation and reactions from members of the United States congress, the United States Department of State declared Acosta Persona non grata.[35][36]

Despite the withdrawal of SEBIN agents, the government of Nicolás Maduro allegedly "maintains a network of spies in the United States, formed by supporters of the Bolivarian Revolution who are paid handsomely," according to former SEBIN officials.[34] The former officials also stated that the contributions of "spies" is maintained by members of the "Patriotas Cooperantes" and from open source contributions, such as from press reports or information posted on websites.[34] The Venezuelan government has used such tactics to reportedly observe government opposition organizations in the United States and has allegedly spied on United States government officials such as Cuban-American senator and representative Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-FL), respectively.[34][38]

On 15 February 2019, General Director Manuel Cristopher Figuera was sanctioned by the United States for suspected human rights violations and torture.[39] Following the Venezuelan uprising on 30 April 2019, the U.S. removed sanctions against Manuel Cristopher Figuera, who broke ranks with Maduro.[40]

Operations

SEBIN operates from two headquarters; El Helicoide the original headquarters of the agency, and "La Tumba", its second and more updated facility.

This federal entity could be considered the only security agency in Venezuela that never participates in any direct involvement with the general public. SEBIN doesn't patrol the public roads, arrest civilians, or do regular law enforcement work like police departments and doesn't participate in any police raids, joint task forces, or operations not related to the ministry of interior and justice. It is an agency that combines their counterparts of the FBI, CIA, Secret Service, and US Marshal core work, such as counterterrorism, intelligence, counterintelligence, government investigations, and background investigations and provides protection/escort for high-ranking government officials, among other federally mandated duties. Officers of this agency are rarely seen in public wearing their full black uniforms; they can be seen providing protection within a few federal buildings throughout the country.

See also

- Dirección de Inteligencia Militar

- Human rights in Venezuela

- Law enforcement in Venezuela

- List of secret police organizations

References

- Krygier, Rachelle; Partlow, Joshua (June 24, 2017). "In Venezuela, prisoners say abuse is so bad they are forced to eat pasta mixed with excrement". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

The headquarters of the Venezuelan intelligence service is a vast pyramid-shaped edifice known as the Helicoide, a former shopping mall which now functions as an interrogation pen for political prisoners and protesters.

- "SERVICIO BOLIVARIANO DE INTELIGENCIA NACIONAL SEBIN - Memoria 2013" (PDF). Vicepresidencia de la República. 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Con su nuevo cargo, Delcy Rodríguez será la responsable del Sebin". La Patilla] (in Spanish). 14 June 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

-

- "REPORT OF THE GENERAL SECRETARIAT OF THE ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES AND THE PANEL OF INDEPENDENT INTERNATIONAL EXPERTS ON THE POSSIBLE COMMISSION OF CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY IN VENEZUELA" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Organization of American States. May 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

The Bolivarian National Intelligence Service are the political police of the Bolivarian Government.

- Ross, Clifton (2016). Home from the Dark Side of Utopia: A Journey through American Revolutions. Oakland, CA: AK Press.

... SEBIN (Bolivarian secret police) ...

- Lares, Fermin (2015). The Chavismo Files. ISBN 9781682138434.

... Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional (Bolivarian Intelligence Service) (SEBIN), the political police of the regime.

- POLITICAL PERSECUTION IN VENEZUELA (PDF). Center for Justice and Peace (CEPAZ). June 2015. p. 64. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

The body of research commissioned for the cases is the political police, the SEBIN ...

- Trinkunas, Harold (20 February 2014). "Toward a Peaceful Solution for Venezuela's Crisis". Brookings Institution. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

Already, this has allowed journalists to identify SEBIN agents by name ... and it has led President Maduro to fire the head of the political police

- "Confusion swirls around Venezuelan prison revolt where US. citizen is detained". The Miami Herald. 17 May 2018. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

Political police officers from SEBIN ...

- Cristóbal Nagel, Juan (16 October 2015). "Venezuela's Other Political Prisoners". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

Venezuela’s political police, the SEBIN, ...

- "TalCual: Sebin Rules in Venezuela". Latin American Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

The use of the civil justice system to repress dissent seems not to be working as well as it should for the Government anymore and for that reason Sebin, Venezuela’s political police force, is trying to get the control of the courts of justice by forcing some of their judges to comply with its orders.

- "'Please Help Me!' American Caught In Venezuelan Prison Riot Pleads On Video". NPR. 17 May 2018. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

... Venezuelan political police headquarters, SEBIN, ...

- Márquez, Humberto (7 March 2014). "Gun Violence Darkens Political Unrest in Venezuela". Inter Press Service. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

Agents of the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN, the political police) were present ...

- "El Sebin, la policía secreta que solo responde a Nicolás Maduro". La República (in Spanish). 2017-08-13. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

El Sebin, la policía secreta que solo responde a Nicolás Maduro (The Sebin, the secret police that only responds to Nicolás Maduro)

- "El accionar de la temible policía secreta chavista - Edicion Impresa". ABC Color (in Spanish). 23 July 2017. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

El Sebin, policía secreta del régimen chavista (The Sebin, the secret police of the chavista regime)

- "REPORT OF THE GENERAL SECRETARIAT OF THE ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES AND THE PANEL OF INDEPENDENT INTERNATIONAL EXPERTS ON THE POSSIBLE COMMISSION OF CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY IN VENEZUELA" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Organization of American States. May 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- OAS (2009-08-01). "OAS - Organization of American States: Democracy for peace, security, and development". www.oas.org. Retrieved 2019-07-27.

- "OAS says Venezuela is the region's top priority". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2019-07-27.

- "CIA declassified document 926816, October 13, 1976" (PDF). Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- "Human Rights Watch World Report 2001: Venezuela: Human Rights Developments". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- "HRW World Report 1999: Venezuela: Human Rights Developments". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- "Letter to President Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías (Human Rights Watch, 12-4-2004)". hrw.org. Archived from the original on 2004-04-30. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- "Human Rights in Venezuela" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. October 1993.

- 1997 AI Report Archived June 1, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- 1998 AI Report Archived June 1, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- Zerpa, Fabiola (18 May 2014). "Abran la puerta, es el Sebin". El Nacional. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Venezuelan Disip to be now designated as Bolivarian Intelligence Service. ABN Accessed on December 4th, 2009

- "Un calabozo macabro". Univision. 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- Vinogradoff, Ludmila (10 February 2015). ""La tumba", siete celdas de tortura en el corazón de Caracas". ABC. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "UNEARTHING THE TOMB: INSIDE VENEZUELA'S SECRET UNDERGROUND TORTURE CHAMBER". Fusion. 2015. Archived from the original on July 29, 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Political protesters are left to rot in Venezuela's secretive underground prison". News.com.au. 25 July 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "tatement of Santiago A. Canton Executive Director, RFK Partners for Human Rights Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights" (PDF). United States Senate. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 29, 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Abogados denuncian que el Sebin realiza seguimientos para amedrentarlos". El Nacional. 19 May 2014. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- "Associated Press announces 2017 staff awards". Associated Press. 23 June 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "Departing AP reporter looks back at Venezuela's slide". The Washington Post. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "El Nuevo Herald: Gobierno gasta millones en espionaje electrónico de sus ciudadanos". La Patilla. 2 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- "Venezuela: ya son siete los tuiteros detenidos por "opiniones inadecuadas"". Infobae. 1 November 2014. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- "Netizen Report: Leaked Documents Reveal Egregious Abuse of Power by Venezuela in Twitter Arrests". Global Voices Online. 17 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- Filar, Ray (5 February 2013). "Venezuela 'spying' on Jewish community". The JC. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- "Venezuela spying on its Jews, documents reveal". The Times of Israel. 31 January 2014. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- "VENEZUELA Protestors in civil disturbances". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on March 22, 2004. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- Neuman, William (26 February 2014). "Venezuela Accuses Intelligence Officers of Murdering 2". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- "Foreign journal provides identity of shooters". El Universal. 19 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- Gupta, Girish (17 February 2014). "Venezuelan security forces raid major opposition base". USA Today. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- Rhodan, Maya (9 March 2015). "White House Sanctions Seven Officials in Venezuela". Time. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Maria Delgado, Antonio (16 November 2014). "El régimen de Maduro mantiene una red de espías en Estados Unidos". El Nuevo Herald. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- "Expulsan a Cónsul de Venezuela en Miami mencionada en documental de Univision". Univision. 8 January 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- "US expels Venezuela's Miami consul Livia Acosta Noguera". BBC. 9 January 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- "U.S. expels Venezuelan diplomat in Miami". CNN. 9 January 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- Derby, Kevin (18 November 2014). "Nicolas Maduro's Regime Spies on Marco Rubio and Ileana Ros-Lehtinen". Sunshine State News. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- "Manuel Quevedo entre los cinco funcionarios de Maduro sancionados por EEUU". La Patilla (in Spanish). 2019-02-15. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- Ramptom, Roberta (7 May 2019). "U.S. lifts sanctions on Venezuelan general who broke with Maduro". Reuters. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bolivarian Intelligence Service. |