Sound barrier

The sound barrier or sonic barrier is the sudden increase in aerodynamic drag and other undesirable effects experienced by an aircraft or other object when it approaches the speed of sound. When aircraft first approached the speed of sound, these effects were seen as constituting a barrier making faster speeds very difficult or impossible.[3][4] The term sound barrier is still sometimes used today to refer to aircraft reaching supersonic flight. Flying faster than sound produces a sonic boom.

_-_filtered.jpg.webp)

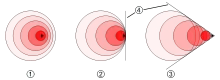

- Subsonic

- Mach 1

- Supersonic

- Shock wave

In dry air at 20 °C (68 °F), the speed of sound is 343 metres per second (about 767 mph, 1234 km/h or 1,125 ft/s). The term came into use during World War II when pilots of high-speed fighter aircraft experienced the effects of compressibility, a number of adverse aerodynamic effects that deterred further acceleration, seemingly impeding flight at speeds close to the speed of sound. These difficulties represented a barrier to flying at faster speeds. In 1947, American test pilot Chuck Yeager demonstrated that safe flight at the speed of sound was achievable in purpose-designed aircraft, thereby breaking the barrier. By the 1950s, new designs of fighter aircraft routinely reached the speed of sound, and faster.[N 1]

History

Some common whips such as the bullwhip or stockwhip are able to move faster than sound: the tip of the whip exceeds this speed and causes a sharp crack—literally a sonic boom.[5] Firearms made after the 19th century generally have a supersonic muzzle velocity.[6]

The sound barrier may have been first breached by living beings about 150 million years ago. Some paleobiologists report that, based on computer models of their biomechanical capabilities, certain long-tailed dinosaurs such as Brontosaurus, Apatosaurus, and Diplodocus may have been able to flick their tails at supersonic speeds, creating a cracking sound. This finding is theoretical and disputed by others in the field.[7] Meteors entering the Earth's atmosphere usually, if not always, descend faster than sound.

Early problems

The tip of the propeller on many early aircraft may reach supersonic speeds, producing a noticeable buzz that differentiates such aircraft. This is undesirable, as the transonic air movement creates disruptive shock waves and turbulence. It is due to these effects that propellers are known to suffer from dramatically decreased performance as they approach the speed of sound. It is easy to demonstrate that the power needed to improve performance is so great that the weight of the required engine grows faster than the power output of the propeller can compensate. This problem was one that led to early research into jet engines, notably by Frank Whittle in England and Hans von Ohain in Germany, who were led to their research specifically in order to avoid these problems in high-speed flight.

Nevertheless, propeller aircraft were able to approach the critical Mach number in a dive. Unfortunately, doing so led to numerous crashes for a variety of reasons. Most infamously, in the Mitsubishi Zero, pilots flew at full power into the terrain because the rapidly increasing forces acting on the control surfaces of their aircraft overpowered them.[8] In this case, several attempts to fix it only made the problem worse. Likewise, the flexing caused by the low torsional stiffness of the Supermarine Spitfire's wings caused them, in turn, to counteract aileron control inputs, leading to a condition known as control reversal. This was solved in later models with changes to the wing. Worse still, a particularly dangerous interaction of the airflow between the wings and tail surfaces of diving Lockheed P-38 Lightnings made "pulling out" of dives difficult; however, the problem was later solved by the addition of a "dive flap" that upset the airflow under these circumstances. Flutter due to the formation of shock waves on curved surfaces was another major problem, which led most famously to the breakup of a de Havilland Swallow and death of its pilot Geoffrey de Havilland, Jr. on 27 September 1946. A similar problem is thought to have been the cause of the 1943 crash of the BI-1 rocket aircraft in the Soviet Union.

All of these effects, although unrelated in most ways, led to the concept of a "barrier" making it difficult for an aircraft to exceed the speed of sound.[9] Erroneous news reports caused most people to envision the sound barrier as a physical "wall", which supersonic aircraft needed to "break" with a sharp needle nose on the front of the fuselage. Rocketry and artillery experts' products routinely exceeded Mach 1, but aircraft designers and aerodynamic engineers during and after World War II discussed Mach 0.7 as a limit dangerous to exceed.[10]

Early claims

During WWII and immediately thereafter, a number of claims were made that the sound barrier had been broken in a dive. The majority of these purported events can be dismissed as instrumentation errors. The typical airspeed indicator (ASI) uses air pressure differences between two or more points on the aircraft, typically near the nose and at the side of the fuselage, to produce a speed figure. At high speed, the various compression effects that lead to the sound barrier also cause the ASI to go non-linear and produce inaccurately high or low readings, depending on the specifics of the installation. This effect became known as "Mach jump".[11] Before the introduction of Mach meters, accurate measurements of supersonic speeds could only be made remotely, normally using ground-based instruments. Many claims of supersonic speeds were found to be far below this speed when measured in this fashion.

In 1942, Republic Aviation issued a press release stating that Lts. Harold E. Comstock and Roger Dyar had exceeded the speed of sound during test dives in a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. It is widely agreed that this was due to inaccurate ASI readings. In similar tests, the North American P-51 Mustang demonstrated limits at Mach 0.85, with every flight over M0.84 causing the aircraft to be damaged by vibration.[12]

One of the highest recorded instrumented Mach numbers attained for a propeller aircraft is the Mach 0.891 for a Spitfire PR XI, flown during dive tests at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough in April 1944. The Spitfire, a photo-reconnaissance variant, the Mark XI, fitted with an extended "rake type" multiple pitot system, was flown by Squadron Leader J. R. Tobin to this speed, corresponding to a corrected true airspeed (TAS) of 606 mph.[13] In a subsequent flight, Squadron Leader Anthony Martindale achieved Mach 0.92, but it ended in a forced landing after over-revving damaged the engine.[14]

Hans Guido Mutke claimed to have broken the sound barrier on 9 April 1945 in the Messerschmitt Me 262 jet aircraft. He states that his ASI pegged itself at 1,100 kilometres per hour (680 mph). Mutke reported not just transonic buffeting, but the resumption of normal control once a certain speed was exceeded, then a resumption of severe buffeting once the Me 262 slowed again. He also reported engine flame-out.[15]

This claim is widely disputed, even by pilots in his unit.[16] All of the effects he reported are known to occur on the Me 262 at much lower speeds, and the ASI reading is simply not reliable in the transonic. Further, a series of tests made by Karl Doetsch at the behest of Willy Messerschmitt found that the plane became uncontrollable above Mach 0.86, and at Mach 0.9 would nose over into a dive that could not be recovered from. Post-war tests by the RAF confirmed these results, with the slight modification that the maximum speed using new instruments was found to be Mach 0.84, rather than Mach 0.86.[17]

In 1999, Mutke enlisted the help of Professor Otto Wagner of the Munich Technical University to run computational tests to determine whether the aircraft could break the sound barrier. These tests do not rule out the possibility, but are lacking accurate data on the coefficient of drag that would be needed to make accurate simulations.[18][19] Wagner stated: "I don't want to exclude the possibility, but I can imagine he may also have been just below the speed of sound and felt the buffeting, but did not go above Mach-1."[16]

One bit of evidence presented by Mutke is on page 13 of the "Me 262 A-1 Pilot's Handbook" issued by Headquarters Air Materiel Command, Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio as Report No. F-SU-1111-ND on January 10, 1946:

Speeds of 950 km/h (590 mph) are reported to have been attained in a shallow dive 20° to 30° from the horizontal. No vertical dives were made. At speeds of 950 to 1,000 km/h (590 to 620 mph) the air flow around the aircraft reaches the speed of sound, and it is reported that the control surfaces no longer affect the direction of flight. The results vary with different airplanes: some wing over and dive while others dive gradually. It is also reported that once the speed of sound is exceeded, this condition disappears and normal control is restored.

The comments about restoration of flight control and cessation of buffeting above Mach 1 are very significant in a 1946 document. However, it is not clear where these terms came from, as it does not appear the US pilots carried out such tests.[18]

In his 1990 book Me-163, former Messerschmitt Me 163 "Komet" pilot Mano Ziegler claims that his friend, test pilot Heini Dittmar, broke the sound barrier while diving the rocket plane, and that several people on the ground heard the sonic booms. He claims that on 6 July 1944, Dittmar, flying Me 163B V18, bearing the Stammkennzeichen alphabetic code VA+SP, was measured traveling at a speed of 1,130 km/h (702 mph).[20] However, no evidence of such a flight exists in any of the materials from that period, which were captured by Allied forces and extensively studied.[21] Dittmar had been officially recorded at 1,004.5 km/h (623.8 mph) in level flight on 2 October 1941 in the prototype Me 163A V4. He reached this speed at less than full throttle, as he was concerned by the transonic buffeting. Dittmar himself does not make a claim that he broke the sound barrier on that flight and notes that the speed was recorded only on the AIS. He does, however, take credit for being the first pilot to "knock on the sound barrier".[16]

The Luftwaffe test pilot Lothar Sieber (7 April 1922 – 1 March 1945) may have inadvertently become the first man to break the sound barrier on 1 March 1945. This occurred while he was piloting a Bachem Ba 349 "Natter" for the first manned vertical takeoff of a rocket in history. In 55 seconds, he traveled a total of 14 km (8.7 miles). The aircraft crashed, and he perished violently in this endeavor.[22]

There are a number of unmanned vehicles that flew at supersonic speeds during this period, but they generally do not meet the definition. In 1933, Soviet designers working on ramjet concepts fired phosphorus-powered engines out of artillery guns to get them to operational speeds. It is possible that this produced supersonic performance as high as Mach 2,[23] but this was not due solely to the engine itself. In contrast, the German V-2 ballistic missile routinely broke the sound barrier in flight, for the first time on 3 October 1942. By September 1944, V-2s routinely achieved Mach 4 (1,200 m/s, or 3044 mph) during terminal descent.

Breaking the sound barrier

In 1942, the United Kingdom's Ministry of Aviation began a top-secret project with Miles Aircraft to develop the world's first aircraft capable of breaking the sound barrier. The project resulted in the development of the prototype Miles M.52 turbojet-powered aircraft, which was designed to reach 1,000 mph (417 m/s; 1,600 km/h) (over twice the existing speed record) in level flight, and to climb to an altitude of 36,000 ft (11 km) in 1 minute 30 seconds.

A huge number of advanced features were incorporated into the resulting M.52 design, many of which hint at a detailed knowledge of supersonic aerodynamics. In particular, the design featured a conical nose and sharp wing leading edges, as it was known that round-nosed projectiles could not be stabilised at supersonic speeds. The design used very thin wings of biconvex section proposed by Jakob Ackeret for low drag. The wing tips were "clipped" to keep them clear of the conical shock wave generated by the nose of the aircraft. The fuselage had the minimum cross-section allowable around the centrifugal engine with fuel tanks in a saddle over the top.

Another critical addition was the use of a power-operated stabilator, also known as the all-moving tail or flying tail, a key to supersonic flight control, which contrasted with traditional hinged tailplanes (horizontal stabilizers) connected mechanically to the pilots control column. Conventional control surfaces became ineffective at the high subsonic speeds then being achieved by fighters in dives, due to the aerodynamic forces caused by the formation of shockwaves at the hinge and the rearward movement of the centre of pressure, which together could override the control forces that could be applied mechanically by the pilot, hindering recovery from the dive.[24][25] A major impediment to early transonic flight was control reversal, the phenomenon which caused flight inputs (stick, rudder) to switch direction at high speed; it was the cause of many accidents and near-accidents. An all-flying tail is considered to be a minimum condition of enabling aircraft to break the transonic barrier safely, without losing pilot control. The Miles M.52 was the first instance of this solution, which has since been universally applied.

Initially, the aircraft was to use Frank Whittle's latest engine, the Power Jets W.2/700, which would only reach supersonic speed in a shallow dive. To develop a fully supersonic version of the aircraft, an innovation incorporated was a reheat jetpipe – also known as an afterburner. Extra fuel was to be burned in the tailpipe to avoid overheating the turbine blades, making use of unused oxygen in the exhaust.[26] Finally, the design included another critical element – the use of a shock cone in the nose to slow the incoming air to the subsonic speeds needed by the engine.

Although the project was eventually cancelled, the research was used to construct an unmanned missile that went on to achieve a speed of Mach 1.38 in a successful, controlled transonic and supersonic level test flight; this was a unique achievement at that time, which validated the aerodynamics of the M.52.

Meanwhile, test pilots achieved high velocities in the tailless, swept-wing de Havilland DH 108. One of them was Geoffrey de Havilland, Jr., who was killed on 27 September 1946 when his DH 108 broke up at about Mach 0.9.[27] John Derry has been called "Britain's first supersonic pilot"[28] because of a dive he made in a DH 108 on 6 September 1948.

The first "official" aircraft to break the sound barrier

The British Air Ministry signed an agreement with the United States to exchange all its high-speed research, data and designs and Bell Aircraft company was given access to the drawings and research on the M.52,[29] but the U.S. reneged on the agreement, and no data was forthcoming in return.[30] Bell's supersonic design was still using a conventional tail, and they were battling the problem of control.[31]

They utilized the information to initiate work on the Bell X-1. The final version of the Bell X-1 was very similar in design to the original Miles M.52 version. Also featuring the all-moving tail, the XS-1 was later known as the X-1. It was in the X-1 that Chuck Yeager was credited with being the first person to break the sound barrier in level flight on 14 October 1947, flying at an altitude of 45,000 ft (13.7 km). George Welch made a plausible but officially unverified claim to have broken the sound barrier on 1 October 1947, while flying an XP-86 Sabre. He also claimed to have repeated his supersonic flight on 14 October 1947, 30 minutes before Yeager broke the sound barrier in the Bell X-1. Although evidence from witnesses and instruments strongly imply that Welch achieved supersonic speed, the flights were not properly monitored and are not officially recognized. The XP-86 officially achieved supersonic speed on 26 April 1948.[32]

On 14 October 1947, just under a month after the United States Air Force had been created as a separate service, the tests culminated in the first manned supersonic flight, piloted by Air Force Captain Charles "Chuck" Yeager in aircraft #46-062, which he had christened Glamorous Glennis. The rocket-powered aircraft was launched from the bomb bay of a specially modified B-29 and glided to a landing on a runway. XS-1 flight number 50 is the first one where the X-1 recorded supersonic flight, at Mach 1.06 (361 m/s, 1,299 km/h, 807.2 mph) peak speed; however, Yeager and many other personnel believe that Flight #49 (also with Yeager piloting), which reached a top recorded speed of Mach 0.997 (339 m/s, 1,221 km/h), may have, in fact, exceeded Mach 1. (The measurements were not accurate to three significant figures and no sonic boom was recorded for that flight.)

As a result of the X-1's initial supersonic flight, the National Aeronautics Association voted its 1948 Collier Trophy to be shared by the three main participants in the program. Honored at the White House by President Harry S. Truman were Larry Bell for Bell Aircraft, Captain Yeager for piloting the flights, and John Stack for the NACA contributions.

Jackie Cochran was the first woman to break the sound barrier on 18 May 1953, in a Canadair Sabre, with Yeager as her wingman.

On 21 August 1961, a Douglas DC-8-43 (registration N9604Z) unofficially exceeded Mach 1 in a controlled dive during a test flight at Edwards Air Force Base, as observed and reported by the flight crew; the crew were William Magruder (pilot), Paul Patten (co-pilot), Joseph Tomich (flight engineer), and Richard H. Edwards (flight test engineer).[33] This was the first supersonic flight by a civilian airliner, and the only one other than those by Concorde or the Tu-144.[33]

The sound barrier understood

As the science of high-speed flight became more widely understood, a number of changes led to the eventual understanding that the "sound barrier" is easily penetrated, with the right conditions. Among these changes were the introduction of thin swept wings, the area rule, and engines of ever-increasing performance. By the 1950s, many combat aircraft could routinely break the sound barrier in level flight, although they often suffered from control problems when doing so, such as Mach tuck. Modern aircraft can transit the "barrier" without control problems.[34]

By the late 1950s, the issue was so well understood that many companies started investing in the development of supersonic airliners, or SSTs, believing that to be the next "natural" step in airliner evolution. However, this has not yet happened. Although the Concorde and the Tupolev Tu-144 entered service in the 1970s, both were later retired without being replaced by similar designs. The last flight of a Concorde in service was in 2003.

Although Concorde and the Tu-144 were the first aircraft to carry commercial passengers at supersonic speeds, they were not the first or only commercial airliners to break the sound barrier. On 21 August 1961, a Douglas DC-8 broke the sound barrier at Mach 1.012, or 1,240 km/h (776.2 mph), while in a controlled dive through 41,088 feet (12,510 m). The purpose of the flight was to collect data on a new design of leading edge for the wing.[35] A China Airlines 747 may have broken the sound barrier in an unplanned descent from 41,000 ft (12,500 m) to 9,500 ft (2,900 m) after an in-flight upset on 19 February 1985. It also reached over 5g.[36]

Breaking the sound barrier in a land vehicle

On 12 January 1948, a Northrop unmanned rocket sled became the first land vehicle to break the sound barrier. At a military test facility at Muroc Air Force Base (now Edwards AFB), California, it reached a peak speed of 1,019 mph (1,640 km/h) before jumping the rails.[37][38]

On 15 October 1997, in a vehicle designed and built by a team led by Richard Noble, Royal Air Force pilot Andy Green became the first person to break the sound barrier in a land vehicle in compliance with Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile rules. The vehicle, called the ThrustSSC ("Super Sonic Car"), captured the record 50 years and one day after Yeager's first supersonic flight.

Felix Baumgartner

In October 2012 Felix Baumgartner, with a team of scientists and sponsor Red Bull, attempted the highest sky-dive on record. The project would see Baumgartner attempt to jump 120,000 ft (36,580 m) from a helium balloon and become the first parachutist to break the sound barrier. The launch was scheduled for 9 October 2012, but was aborted due to adverse weather; subsequently the capsule was launched instead on 14 October. Baumgartner's feat also marked the 65th anniversary of U.S. test pilot Chuck Yeager's successful attempt to break the sound barrier in an aircraft.[39]

Baumgartner landed in eastern New Mexico after jumping from a world record 128,100 feet (39,045 m), or 24.26 miles, and broke the sound barrier as he traveled at speeds up to 833.9 mph (1342 km/h, or Mach 1.26). In the press conference after his jump, it was announced that he was in freefall for 4 minutes 18 seconds, the second longest freefall after the 1960 jump of Joseph Kittinger for 4 minutes 36 seconds.[39]

Alan Eustace

In October 2014, Alan Eustace, a senior vice president at Google, broke Baumgartner's record for highest sky-dive and also broke the sound barrier in the process.[40] However, because Eustace's jump involved a drogue parachute, while Baumgartner's did not, their vertical speed and free-fall distance records remain in different categories.[41][42]

Legacy

David Lean directed The Sound Barrier, a fictionalized retelling of the de Havilland DH 108 test flights.

See also

References

Notes

- See "Speed of sound" for the science behind the velocity called the sound barrier, and "Sonic boom" for information on the sound associated with supersonic flight.

Citations

- Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (19 August 2007). "A Sonic Boom". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- "F-14 Condensation cloud in action". web.archive.org. Retrieved: August 30, 2010.

- sonic barrier Archived 2016-10-13 at the Wayback Machine. thefreedictionary.com.

- sound barrier Archived 2015-04-11 at the Wayback Machine. oxforddictionaries.com.

- May, Mike. "Crackin' good mathematics" Archived 2016-03-22 at the Wayback Machine. American Scientist, Volume 90, Issue 5, September–October 2002. p. 1.

- "The Accuracy of Black Powder Muskets" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- Wilford, John Noble. "Did Dinosaurs Break the Sound Barrier?" Archived 2020-12-08 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, December 2, 1997. Retrieved: January 15, 2009.

- Yoshimura, Akira, translated by Retsu Kaiho and Michael Gregson (1996). Zero! Fighter. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Praeger Publishers. p. 108. ISBN 0-275-95355-6.

- Portway, Donald (1940). Military Science Today. London: Oxford University Press. p. 18: "For various reasons it is fairly certain that the maximum attainable speed under self-propelled conditions will be that of sound in air", i.e., 750 mph (1,210 km/h).

- Ley, Willy (November 1948). "The 'Brickwall' in the Sky". Astounding Science Fiction. pp. 78–99.

- Jordan, Corey C. "The Amazing George Welch, Part Two, First Through the Sonic Wall" Archived 2012-03-25 at the Wayback Machine. Planes and Pilots Of World War Two, 1998–2000. Retrieved: June 12, 2011.

- Compressibility Dive Tests on the North American P-51D Airplane, (‘Mustang IV’) AAF No.44-14134 (Technical report). Wright Field. 9 October 1944.

- Spitfire – Typical high speed dive Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine. spitfireperformance.com.

- Dick, Steven J., ed. (2010). NASA's First 50 Years: Historical Perspectives (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-16-084965-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-12-25. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- Mutke, Hans Guido. "The Unknown Pilot". Archived from the original on 6 February 2005.

- "Nazi-era pilot says he broke sound barrier first". news24. 12 August 2001. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- "Me 262 and the Sound Barrier". Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine aerospaceweb.org. Retrieved: August 30, 2010.

- Schulz, Matthias (19 February 2001). "Flammenritt über dem Moor". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- "Pilot claims he broke sound barrier first". USA Today. 19 June 2001. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- Käsmann, Ferdinand C. W. (1999) Die schnellsten Jets der Welt (in German). Berlin: Aviatic-Verlag GmbH. pp. 17, 122. ISBN 3-925505-26-1.

- Dunning, Brian (19 May 2009). "Skeptoid #154: Was Chuck Yeager the First to Break the Sound Barrier?". Skeptoid. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- "Historical Footnote: On March 1st 1945, did Lothar Sieber become the first person to break the sound barrier?" Archived 2013-10-03 at the Wayback Machine Doug's Darkworld: War, Science, and Philosophy in a Fractured World, November 25, 2008. Retrieved: November 18, 2012.

- Durant, Frederick C. and George S. James. "Early Experiments with Ramjet Engines in Flight". First Steps Toward Space: Proceedings of the First and Second History Symposia of the International Academy of Astronautics at Belgrade, Yugoslavia, September 26, 1967. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1974.

- Brown, Eric (August–November 1980). "Miles M.52: The Supersonic Dream". Air Enthusiast Thirteen. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Beamont, Roland. Testing Early Jets. London: Airlife, 1990. ISBN 1-85310-158-3.

- "Miles on Supersonic Flight". Aviation History: 355. 3 October 1946. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- Watkins, David (1996), de Havilland Vampire: The Complete History, Thrupp, Gloucestershire: Budding Books, p. 40, ISBN 1-84015-023-8.

- Rivas, Brian, and Bullen, Annie (1996), John Derry: The Story of Britain's First Supersonic Pilot, William Kimber, ISBN 0-7183-0099-8.

- Wood, Derek (1975). Project Cancelled. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company Inc. p. 36. ISBN 0-672-52166-0.

- Bancroft, Dennis. "Faster Than Sound" Archived 2017-08-29 at the Wayback Machine. NOVA Transcripts, PBS, air date: 14 October 1997. Retrieved: 26 April 2009.

- Miller, Jay. The X-Planes: X-1 to X-45. Hinckley, UK: Midland, 2001. ISBN 1-85780-109-1.

- Wagner, Ray (1963). The North American Sabre. London: Macdonald. p. 17.

- Wasserzieher, Bill (August 2011). "I Was There: When the DC-8 Went Supersonic". Air & Space Magazine. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- barrier/source.html "Sound Barrier". DiracDelta.co.uk: Science and Engineering Encyclopedia. Retrieved: October 14, 2012.

- "Douglas Passenger Jet Breaks Sound Barrier" Archived 2006-10-26 at the Wayback Machine. dc8.org. Retrieved: August 30, 2010.

- "China Airlines Flight 006" Archived 2011-09-18 at the Wayback Machine. aviation-safety.net. Retrieved: August 30, 2010.

- "A rocket powered sled runs along the ground on the rails in Muroc" Archived 2011-03-22 at the Wayback Machine. Universal International News, January 22, 1948. Retrieved: September 9, 2011.

- "NASA Timeline" Archived 2012-10-20 at the Wayback Machine. NASA. Retrieved: September 9, 2011.

- Sunseri, Gina and Kevin Doak. "Felix Baumgartner: Daredevil Lands on Earth After Record Breaking Supersonic Leap" Archived 2020-11-11 at the Wayback Machine. ABC News, October 14, 2012.

- John Markoff. "Alan Eustace Jumps From Stratosphere, Breaking Felix Baumgartner’s World Record" Archived 2019-06-16 at the Wayback Machine. New York Times. October 24, 2014.

- "Baumgartner's Records Ratified by FAI!". FAI. February 22, 2013. Archived from the original on March 14, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- "Alan Eustace, D-7426, Bests High-Altitude World Record". U.S. Parachute Association. October 24, 2014. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

Bibliography

- "Breaking the Sound Barrier." Modern Marvels (TV program). July 16, 2003.

- Hallion, Dr. Richard P. "Saga of the Rocket Ships." AirEnthusiast Five, November 1977 – February 1978. Bromley, Kent, UK: Pilot Press Ltd., 1977.

- Miller, Jay. The X-Planes: X-1 to X-45, Hinckley, UK: Midland, 2001. ISBN 1-85780-109-1.

- Pisano, Dominick A., R. Robert van der Linden and Frank H. Winter. Chuck Yeager and the Bell X-1: Breaking the Sound Barrier. Washington, DC: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (in association with Abrams, New York), 2006. ISBN 0-8109-5535-0.

- Radinger, Willy and Walter Schick. Me 262 (in German). Berlin: Avantic Verlag GmbH, 1996. ISBN 3-925505-21-0.

- Rivas, Brian (2012), A Very British Sound Barrier: DH 108, A Story of Courage, Triumph and Tragedy, Walton-on-Thames, Surrey: Red Kite, ISBN 978-1-90659-204-2.

- Winchester, Jim. "Bell X-1." Concept Aircraft: Prototypes, X-Planes and Experimental Aircraft (The Aviation Factfile). Kent, UK: Grange Books plc, 2005. ISBN 978-1-84013-809-2.

- Wolfe. Tom. The Right Stuff. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979. ISBN 0-374-25033-2.

- Yeager, Chuck, Bob Cardenas, Bob Hoover, Jack Russell and James Young. The Quest for Mach One: A First-Person Account of Breaking the Sound Barrier. New York: Penguin Studio, 1997. ISBN 0-670-87460-4.

- Yeager, Chuck and Leo Janos. Yeager: An Autobiography. New York: Bantam, 1986. ISBN 0-553-25674-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sound barrier. |

- Fluid Mechanics, a collection of tutorials by Dr. Mark S. Cramer, Ph.D

- Breaking the Sound Barrier with an Aircraft by Carl Rod Nave, Ph.D

- a video of a Concorde reaching Mach 1 at intersection TESGO taken from below

- An interactive Java applet, illustrating the sound barrier.