Đại Việt

Đại Việt (大越, IPA: [ɗâjˀ vìət]; literally Great Viet), often known as Annam, was a Vietnamese kingdom and sovereign state on Eastern Mainland Southeast Asia from the 10th century AD to the early 19th century. Its early name, Đại Cồ Việt (大瞿越), was established in 968 by Vietnamese ruler Đinh Bộ Lĩnh after he ended the Anarchy of the 12 Warlords, until the beginning of the reign of Lý Thánh Tông (r. 1054–1072), the third emperor of the Lý dynasty. Đại Việt lasted until the reign of Gia Long (r. 1802–1820), the first emperor of the Nguyễn dynasty, when the name was changed to Việt Nam (越南).[4][5][6]

Kingdom of Đại Việt Đại Việt Quốc (大越國) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 968–14071428–1804 | |||||||||

Flag of the Tây Sơn Dynasty in 1778

Royal Standard

| |||||||||

Dai Viet (green) during late 18th century | |||||||||

| Capital | Hoa Lư (968–1010)Thăng Long (Hanoi) (1010–1398, 1428–1789)Thanh Hóa (1398–1407)Phú Xuân (1789–1802)Huế (1802–1804) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Official Vietnamese | ||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism (State religion from 968 to 1400) Taoism Confucianism (State ideolody from 1428 to 1883) Vietnamese folk religion Catholicism Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King or Emperor | |||||||||

• 968–979 | Đinh Bộ Lĩnh | ||||||||

• 1802–1820 | Gia Long | ||||||||

| Historical era | Postclassical era to Late modern period | ||||||||

• End of Third Chinese domination of Vietnam | 905 | ||||||||

| 968 | |||||||||

• Lý Thánh Tông shortened Vietnam's name from Đại Cồ Việt to Đại Việt | 1054 | ||||||||

• Renamed Đại Ngu under the Hồ dynasty | 1400–1407 | ||||||||

| 1407–1427 | |||||||||

| 17 February 1804 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1480 est. | 620,000 km2 (240,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Currency | Vietnamese văn, banknote | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

| Nước Đại Việt[2][3] | |

|---|---|

| Vietnamese name | |

| Vietnamese | Nước Đại Việt |

| Hán-Nôm | 渃大越 |

| History of Vietnam (Names of Vietnam) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Đại Việt is the second-longest used name for Vietnam after "Văn Lang".[7] Its history is divided into the seven royal dynasties of the Đinh (968–980), Early Lê (980–1009), Lý (1009–1226), Trần (1226–1400), and Later Lê (1428–1789); the Mạc dynasty (1527–1677); and the brief Tây Sơn dynasty (1778–1802). It was briefly interrupted by the Hồ (1400–1407), which used the name Đại Ngu (大虞),[8][9] and the Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam (1407–1427) when the region was administered as Jiaozhi.[10]:181

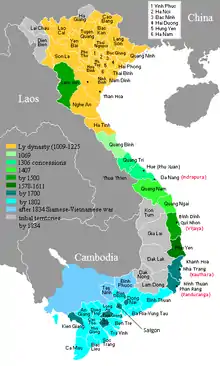

From the 13th to 18th century, Đại Việt's borders expanded to encompass territory that resemble modern-day Vietnam, which lies along the South China Sea from the Gulf of Tonkin to the Gulf of Thailand. Throughout its long existence from 968 to 1804, Đại Việt flourished and acquired significant power in the region. The kingdom slowly annexed Champa's and Cambodia's territories, expanded Vietnamese territories to the south and west.

Etymology

The term "Việt" (Yue) (Chinese: 越; pinyin: Yuè; Cantonese Yale: Yuht; Wade–Giles: Yüeh4; Vietnamese: Việt) in Early Middle Chinese was first written using the logograph "戉" for an axe (a homophone), in oracle bone and bronze inscriptions of the late Shang dynasty (c. 1200 BC), and later as "越".[11] At that time it referred to a people or chieftain to the northwest of the Shang.[12] In the early 8th century BC, a tribe on the middle Yangtze were called the Yangyue, a term later used for peoples further south.[12] Between the 7th and 4th centuries BC Yue/Việt referred to the State of Yue in the lower Yangtze basin and its people.[11][12]

From the 3rd century BC the term was used for the non-Chinese populations of south and southwest China and northern Vietnam, with particular ethnic groups called Minyue, Ouyue, Luoyue (Vietnamese: Lạc Việt), etc., collectively called the Baiyue (Bách Việt, Chinese: 百越; pinyin: Bǎiyuè; Cantonese Yale: Baak Yuet; Vietnamese: Bách Việt; "Hundred Yue/Viet"; ).[11][12] The term Baiyue/Bách Việt first appeared in the book Lüshi Chunqiu compiled around 239 BC.[13] By the 17th and 18th centuries AD, educated Vietnamese apparently referred to themselves as nguoi Viet (Viet people) or nguoi nam (southern people).[14]

History

Origins

For a thousand years, the area of what is now Northern Vietnam was ruled by a succession of Chinese regimes as Giao Châu (交州, Jiaozhou) and Giao Chỉ (交趾, Jiaozhi).

The indigenous inhabitants in Northern Vietnam of ancient kingdom of Nanyue (c. 204 – 111 BC) were known as the Lạc Việt (Luoyue).[2] In 111 BC, Western Han dynasty (c. 202 BC – 9 AD) conquered Nanyue and incorporated the kingdom into Chinese rules, as known as Giao Chỉ. However until the 7th century, the region's population were largely indigenous people.[15]

In 679, the Tang dynasty created Protectorate General to Pacify the South and a military government. In late 9th century, the collapsing Tang dynasty was unable to retain control of the area. Local Viet chieftains and highland people in central Vietnam, in an attempt to overthrow the Tang Chinese influences in the region, allied with Nanzhao.[16] Repeated Nanzhao attack and local rebels from 854 to 866 in Annan ousted the Chinese until Gao Pian recaptured it in 866.[17] In 880, the army in Annan mutinied, took the city of Đại La, and forced the military commissioner Zeng Gun to flee, ending de facto Chinese control in Vietnam.[18][19]

Founding and early period

In 905, a local Vietnamese sinicized chieftain Khúc Thừa Dụ was elected as jiedushi (military governor) of Tĩnh Hải circuit amid the collapsing of Tang Empire.[3][20] This notable event was widely regarded by Vietnamese historians as the reclaim of Vietnamese Independence after a thousand years of Imperial Chinese rules.[21] In 930, Southern Han attacked Annam, decimated the Khuc, but was repulsed by Duong Dinh Nghe in the next year. In 937 Duong Dinh Nghe was assassinated by Kieu Cong Tien, who was assisted by the Southern Han. Ngo Quyen, a warlord from the south killed Kieu Cong Tien, defeated the Southern Han naval invasion in December 938 on the Bach Dang River. Ngo Quyen established himself as king of the Viet with Co Loa as his estates.[22] However, chaos returned after his death in 944, as his two sons were struggling for deposing their uncle Duong Tam Kha out of power, resulted in the Twelve Warlords period.[23]

In 968, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh (r. 968–979) reunited the Viet state[24] under the name of Đại Cồ Việt and claimed the title (emperor).[25] The founder of the kingdom, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh, and his successors, were less sinicized than the previous Khuc family.[26] With assistance of powerful Buddhist monks, Bộ Lĩnh chose Hoa Lư in the southern edge of the Red River Delta as the capital instead of Tang-era Dai La, adopted Chinese-style imperial titles, coinage, and ceremonies and tried to preserve the T’ang administrative framework.[26] In 980 royal powers was transferred to the Lê family of general Lê Hoàn (r. 980–1005), who repelled an Chinese invasion in 981 and invaded Champa in 982.[27] A short period of civil war between princes and princess of Lê Hoàn for succession weakened the royal court. In 1009 Ly Cong Uan deposed the last Early Le king and to become the ruler of Dai Viet.[28]

Late classical period

In 1010, King Lý Thái Tổ relocated the Vietnamese capital from Hoa Lư to Thăng Long (modern-day Hanoi).[29] His son and grandson, Ly Phat Ma (r. 1028–1053) and Ly Nhat Ton (r.1054-1072) led two seaborne attacks against Champa in 1044 and 1069, expanded Vietnamese kingdom to the south, raided Song China in 1053 and 1059, established strong Buddhist institutions around the capital and open the first Confucian classic school in the capital.[30] The Ly abandoned Chinese-style administrative system, divided the country into 24 outer and inner phu (mandalas), with each governed by regional families connecting with the Ly family through royal marriages, that allowed maternal clans to introduce their rivalries at court, but still retained an Sinic techniques to enhance unitary.[31] The fourth Ly king, Ly Can Duc (r.1072-1127) opened the first national civil service examinations in 1075 to recruit officials.[32] The Ly period also saw the creation of a new script called nôm which based on Chinese characters and contain a mix of logographs and phonographs to write Vietnamese language.[33]

The eighth Ly king, Ly Hue Tong (r. 1210–1224) appointed his seven-years-old daughter Ly Chieu Hoang (r.1224–1226) as heir, and abdicated in her favor and became a monk. Tran Thu Do, an high-rank court official, offered Ly Chieu Hoang to marry with his nephew Trần Cảnh, which became Tran Thai Tong (r. 1226–1258), founder of the Tran dynasty of Dai Viet.[34] The ruling Tran (whom may have been descended from Chinese immigrants according to Victor Lieberman) patronized Chinese culture and Chinese-style government more than the previous Ly dynasty. For the first time Chinese-style population registers for each village were set up, civil examinations to recruit literati became larger and more important.[35] The Tran kings also aborted the previous administrative system, appointed their royal members to govern each province.[36]

Following the Mongol conquest of Dali Kingdom in 1253, Mongol army under Uriyangkhadai launched a campaign against Dai Viet in 1258 which resulted in subjugation of Dai Viet to the Yuan empire; however in the second attempt of re-subjugating the Vietnamese and the Cham in 1283, 1285 and 1288, the Yuan armies were repelled.[37]

Chinese conquest and destruction of Dai Viet

In 1400, the Trần was then succeeded by the Hồ dynasty, who claimed descent from the Trần and changed the name of the country to Đại Ngu.[8][9] The Hồ was then conquered by the Chinese Ming dynasty in the Ming–Hồ War of the early 15th century. The region was administered as Giao Chi (Jiaozhi).[10]:181

Revived and unitary period

Fragmentation period

In late 18th century, the Tây Sơn uprising led by the Nguyễn brothers overthrew the Lê dynasty and repelled the invading Qing armies in the Battle of Ngọc Hồi-Đống Đa, considered one of the greatest military victories in Vietnamese history.

In 1802, the Tây Sơn was then overthrown by Gia Long, who founded the Nguyễn dynasty and renamed the country Việt Nam in 1804.[38]

Culture

Traditional beliefs, Confucian study, literature, trade and commerce flourished in Đại Việt and the capital in modern-day Hanoi was a center of trade and industry; its ruins, Imperial Citadel of Thăng Long is the major UNESCO World Heritage Site in Vietnam. The kingdom created great achievements in Vietnamese art and culture, it has left a substantial legacy to modern Vietnam; much of modern Vietnamese culture, language, customs, social norms and nationalism.

Maps

Đại Việt during Dinh dynasty (blue, top right)

Đại Việt during Dinh dynasty (blue, top right) Đại Việt during Lý Dynasty in 1100

Đại Việt during Lý Dynasty in 1100.png.webp) Đại Việt during Tran dynasty (1225-1400) and Ho dynasty (1400–1407)

Đại Việt during Tran dynasty (1225-1400) and Ho dynasty (1400–1407) Đại Việt during the reign of Lê Thánh Tông c. 1480

Đại Việt during the reign of Lê Thánh Tông c. 1480 Đại Việt c. 1540

Đại Việt c. 1540 Đại Việt (Annam) with Mac (green) and Le-Nguyen-Trinh (blue) c. 1570

Đại Việt (Annam) with Mac (green) and Le-Nguyen-Trinh (blue) c. 1570- Đại Việt c. 1650

.png.webp) Đại Việt during Tay Son dynasty

Đại Việt during Tay Son dynasty

Art

10th-century terracotta brick with inscription: "Đại Việt quốc quân thành chuyên" brick to build Great Viet kingdom in Hoa Lư archaeological site

10th-century terracotta brick with inscription: "Đại Việt quốc quân thành chuyên" brick to build Great Viet kingdom in Hoa Lư archaeological site%252C_Bac_Ninh_province%252C_1057_AD_DSC04838.JPG.webp) Amitabha statue of Phat Tich temple, date 1057 AD

Amitabha statue of Phat Tich temple, date 1057 AD Garuda playing the drum, 10-11th century

Garuda playing the drum, 10-11th century Buddha resting statue, Bac Ninh, 17th century

Buddha resting statue, Bac Ninh, 17th century Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvar statue, 17-18th century

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvar statue, 17-18th century Pho Minh pagoda, built in 1262 AD

Pho Minh pagoda, built in 1262 AD The ruins of Thang Long royal palaces

The ruins of Thang Long royal palaces

Timeline (dynasties)

Started in 968 and ended in 1804.

| Ming domination | Nam–Bắc triều * Bắc Hà–Nam Hà | French Indochina | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese domination | Ngô | Đinh | Early Lê | Lý | Trần | Hồ | Later Trần | Lê | Mạc | Revival Lê | Tây Sơn | Nguyễn | Modern time | |||||||

| Trịnh lords | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Nguyễn lords | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 939 | 1009 | 1225 | 1400 | 1427 | 1527 | 1592 | 1788 | 1858 | 1945 | |||||||||||

Notes

References

Citations

- Hall 1981, p. 203.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 51.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 131.

- Lieberman 2003, p. 345.

- Cordier 1875, p. 3.

- Hall 1981, p. 456.

- Dai Viet - Historical Kingdom, Việt Nam.

- Trần, Xuân Sinh (2003). Thuyết Trần. p. 403.

...Quý Ly claims Hồ's ancestor to be Mãn the Duke Hồ [Man, Duke Hu], founding meritorious general of the Chu dynasty, king Ngu Thuấn's [king Shun of Yu] descendant, created his country's name Đại Ngu...

- Trần, Trọng Kim (1919). "I.III.XI.". Việt Nam sử lược. Vol.I.

Quí Ly deposed Thiếu-đế, but respected [the relationship] that he [Thiếu Đế] was his [Quí Ly's] grandson, only demoted him to prince Bảo-ninh 保寧大王, and claimed himself [Quí Ly] the Emperor, changing his surname to Hồ 胡. Originally the surname Hồ [胡 Hu] were descendants of the surname Ngu [虞 Yu] in China, so Quí Ly created a new name for his country Đại-ngu 大虞.

- Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (2011). Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80022-6.

- Norman, Jerry; Mei, Tsu-lin (1976). "The Austroasiatics in Ancient South China: Some Lexical Evidence". Monumenta Serica. 32: 274–301. doi:10.1080/02549948.1976.11731121.

- Meacham, William (1996). "Defining the Hundred Yue". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 15: 93–100. doi:10.7152/bippa.v15i0.11537. Archived from the original on 2014-02-28.

- The Annals of Lü Buwei, translated by John Knoblock and Jeffrey Riegel, Stanford University Press (2000), p. 510. ISBN 978-0-8047-3354-0. "For the most part, there are no rulers to the south of the Yang and Han Rivers, in the confederation of the Hundred Yue tribes."

- Lieberman 2003, p. 405.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 101.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 118.

- Walker 2012, p. 183.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 124.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 114.

- Taylor 2013, p. 44.

- Hall 1981, p. 215.

- Miksic & Yian 2016, p. 346.

- Coedes 2015, p. 80.

- Cotterell 2014, p. 83.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 144.

- Lieberman 2003, p. 353.

- Miksic & Yian 2016, p. 429.

- Coedes 2015, p. 82-83.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 133.

- Coedes 2015, p. 84.

- Lieberman 2003, p. 355-356.

- Lieberman 2003, p. 356.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 135-138.

- Coedes 2015, p. 86.

- Lieberman 2003, p. 360.

- Lieberman 2003, p. 359.

- Miksic & Yian 2016, p. 489.

- Alexander Woodside (1971). Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-0-674-93721-5.

Sources

- Kiernan, Ben (2019). Việt Nam: a history from earliest time to the present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190053796.

- Taylor, Keith W. (2013). A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107244351.

- Chapuis, Oscar (1995). A history of Vietnam: from Hong Bang to Tu Duc. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-29622-7.

- Cordier, Henri (1875). A Narrative of the Recent Events in Tong-King. American Presbyterian Mission Press. ISBN 9780371549506.

- Cotterell, Arthur (2014). A History of Southeast Asia. Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Private Limited. ISBN 9789814634700.

- Hall, Daniel George Edward (1981). History of South East Asia. Macmillan Education, Limited. ISBN 9781349165216.

- Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521663724.

- Reid, Anthony; Nhung Tuyet, Tran, eds. (2016). Viet Nam: Borderless Histories. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316445044.

- Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. Trans: Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- Taylor, Keith W. (2018). Whitmore, John K. (ed.). Essays Into Vietnamese Pasts. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501718991.

- Nguyen, Tai Thu (2008). The History of Buddhism in Vietnam. Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. ISBN 9781565180970.

- Miksic, John Norman; Yian, Go Geok (2016). Ancient Southeast Asia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-317-27903-4.

- Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Integration of the Mainland Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800-1830, Vol 1. Cambridge University Press.

- Li, Tana (2018). Nguyen Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501732577.

- Andaya, Barbara Watson; Andaya, Leonard Y. (2015). A History of Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1400-1830. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521889926.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012). East Asia: A New History. ISBN 978-1477265161.

- Reid, Anthony, ed. (2018). Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Era: Trade, Power, and Belief. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501732171.

- Holcombe, Charles (2017). A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107118737.

- Kang, David C.; Haggard, Stephan, eds. (2020). East Asia in the World: Twelve Events That Shaped the Modern International Order. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108479875.

- Dutton, George; Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K., eds. (2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-51110-0.

- Boudarel, Georges; Nguyen, Van Ky; Nguyễn, Văn Ký (2002). Duiker, Claire (ed.). Hanoi: City of the Rising Dragon. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9780742516557.

- Baldanza, Kathlene (2016). Ming China and Vietnam: Negotiating Borders in Early Modern Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316531310.

- Hoang, Anh Tuấn (2007). Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese relations, 1637-1700. Brill. ISBN 978-9-04-742169-6.

- Coedes, George (2015). The Making of South East Asia (RLE Modern East and South East Asia). Taylor & Francis.

- Hall, Kenneth R. (2019). Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press.

- Baron, Samuel; Borri, Christoforo; Dror, Olga; Duiker, Keith W. (2018). Views of Seventeenth-Century Vietnam: Christoforo Borri on Cochinchina and Samuel Baron on Tonkin. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501720901.

Further reading

- Bridgman, Elijah Coleman (1840). Chronology of Tonkinese Kings. Harvard University. p. 205–212. ISBN 9781377644080.

- Aymonier, Etienne (1893). The Imperial and Asiatic Quarterly Review and Oriental and Colonial Record. Oriental University Institute. ISBN 978-1149974148.

- Cordier, Henri; Yule, Henry, eds. (1993). The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition : Including the Unabridged Third Edition (1903) of Henry Yule's Annotated Translation, as Revised by Henri Cordier, Together with Cordier's Later Volume of Notes and Addenda (1920). Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486275871.

- Harris, Peter (2008). The Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0307269133.

- Wade, Geoff. tr. (2005). Southeast Asia in the Ming Shi-lu: an open access resource. Singapore: Asia Research Institute and the Singapore E-Press, National University of Singapore.

- Pires, Tomé; Rodrigues, Francisco (1990). The Suma oriental of Tome Pires, books 1-5. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120605350.

- Relazione de’ felici successi della santa fede predicata dai Padri della Compagnia di Giesu nel regno di Tunchino (Rome, 1650)

- Tunchinesis historiae libri duo, quorum altero status temporalis hujus regni, altero mirabiles evangelicae predicationis progressus referuntur: Coepta per Patres Societatis Iesu, ab anno 1627, ad annum 1646 (Lyon, 1652)

- Histoire du Royaume de Tunquin, et des grands progrès que la prédication de L’Évangile y a faits en la conversion des infidèles Depuis l’année 1627, jusques à l’année 1646 (Lyon, 1651), translated by Henri Albi

- Divers voyages et missions du P. Alexandre de Rhodes en la Chine et autres royaumes de l'Orient (Paris, 1653), translated into English as Rhodes of Viet Nam: The Travels and Missions of Father Alexandre de Rhodes in China and Other Kingdoms of the Orient (1666)

- La glorieuse mort d'André, Catéchiste (The Glorious Death of Andrew, Catechist) (pub. 1653)

- Royal Geographical Society, The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society: Volume 7 (1837)

External links

- "Dai Viet - Historical Kingdom, Vietnam". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. 2019.