Supply chain management

In commerce, supply chain management (SCM), the management of the flow of goods and services,[2] involves the movement and storage of raw materials, of work-in-process inventory, and of finished goods as well as end to end order fulfilment from point of origin to point of consumption. Interconnected, interrelated or interlinked networks, channels and node businesses combine in the provision of products and services required by end customers in a supply chain.[3] Supply-chain management has been defined[4] as the "design, planning, execution, control, and monitoring of supply-chain activities with the objective of creating net value, building a competitive infrastructure, leveraging worldwide logistics, synchronizing supply with demand and measuring performance globally".[5] SCM practice draws heavily from the areas of industrial engineering, systems engineering, operations management, logistics, procurement, information technology, and marketing[6] and strives for an integrated approach. Marketing channels play an important role in supply-chain management.[6] Current research in supply-chain management is concerned with topics related to sustainability and risk management,[7] among others. Some suggest that the “people dimension” of SCM, ethical issues, internal integration, transparency/visibility, and human capital/talent management are topics that have, so far, been underrepresented on the research agenda.[8] Supply chain management (SCM) is the broad range of activities required to plan, control and execute a product's flow from materials to production to distribution in the most economical way possible. SCM encompasses the integrated planning and execution of processes required to optimize the flow of materials, information and capital in functions that broadly include demand planning, sourcing, production, inventory management and logistics -- or storage and transportation.[9]

| Business administration |

|---|

| Management of a business |

|

.png.webp)

Although it has the same goals as supply chain engineering, supply chain management is focused on a more traditional management and business based approach, whereas supply chain engineering is focused on a mathematical model based one.[10]

Mission

Supply-chain management, techniques with the aim of coordinating all parts of SC from supplying raw materials to delivering and/or resumption of products, tries to minimize total costs with respect to existing conflicts among the chain partners. An example of these conflicts is the interrelation between the sale department desiring to have higher inventory levels to fulfill demands and the warehouse for which lower inventories are desired to reduce holding costs.[11]

Origin of the term and definitions

In 1982, Keith Oliver, a consultant at Booz Allen Hamilton introduced the term "supply chain management" to the public domain in an interview for the Financial Times.[12] In 1983 WirtschaftsWoche in Germany published for the first time the results of an implemented and so called "Supply Chain Management project", led by Wolfgang Partsch.[13]

In the mid-1990s, more than a decade later, the term "supply chain management" gained currency when a flurry of articles and books came out on the subject. Supply chains were originally defined as encompassing all activities associated with the flow and transformation of goods from raw materials through to the end user, as well as the associated information flows. Supply-chain management was then further defined as the integration of supply chain activities through improved supply-chain relationships to achieve a competitive advantage.[12]

In the late 1990s, "supply-chain management" (SCM) rose to prominence, and operations managers began to use it in their titles with increasing regularity.[14][15][16]

Other commonly accepted definitions of supply-chain management include:

- The management of upstream and downstream value-added flows of materials, final goods, and related information among suppliers, company, resellers, and final consumers.[17]

- The systematic, strategic coordination of traditional business functions and tactics across all business functions within a particular company and across businesses within the supply chain, for the purposes of improving the long-term performance of the individual companies and the supply chain as a whole[18]

- A customer-focused definition is given by Hines (2004:p76): "Supply chain strategies require a total systems view of the links in the chain that work together efficiently to create customer satisfaction at the end point of delivery to the consumer. As a consequence, costs must be lowered throughout the chain by driving out unnecessary expenses, movements, and handling. The main focus is turned to efficiency and added value, or the end user's perception of value. Efficiency must be increased, and bottlenecks removed. The measurement of performance focuses on total system efficiency and the equitable monetary reward distribution to those within the supply chain. The supply-chain system must be responsive to customer requirements."[19]

- The integration of key business processes across the supply chain for the purpose of creating value for customers and stakeholders[20][21]

- According to the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP), supply-chain management encompasses the planning and management of all activities involved in sourcing, procurement, conversion, and logistics management. It also includes coordination and collaboration with channel partners, which may be suppliers, intermediaries, third-party service providers, or customers.[6] Supply-chain management integrates supply and demand management within and across companies. More recently, the loosely coupled, self-organizing network of businesses that cooperate to provide product and service offerings has been called the Extended Enterprise.

A supply chain, as opposed to supply-chain management, is a set of organizations directly linked by one or more upstream and downstream flows of products, services, finances, or information from a source to a customer. Supply-chain management is the management of such a chain.[18]

Supply-chain-management software includes tools or modules used to execute supply chain transactions, manage supplier relationships, and control associated business processes.

Supply-chain event management (SCEM) considers all possible events and factors that can disrupt a supply chain. With SCEM, possible scenarios can be created and solutions devised.

In some cases, the supply chain includes the collection of goods after consumer use for recycling or the reverse logistics processes for returning faulty or unwanted products backwards to producers early in the value chain.

Functions

Supply-chain management is a cross-functional approach that includes managing the movement of raw materials into an organization, certain aspects of the internal processing of materials into finished goods, and the movement of finished goods out of the organization and toward the end consumer. As organizations strive to focus on core competencies and become more flexible, they reduce ownership of raw materials sources and distribution channels. These functions are increasingly being outsourced to other firms that can perform the activities better or more cost effectively. The effect is to increase the number of organizations involved in satisfying customer demand, while reducing managerial control of daily logistics operations. Less control and more supply-chain partners lead to the creation of the concept of supply-chain management. The purpose of supply-chain management is to improve trust and collaboration among supply-chain partners thus improving inventory visibility and the velocity of inventory movement.[22] in this section we have to communicate with all the vendors, suppliers and after that we have to take some comparisons after that we have to place the order.

Importance

Organizations increasingly find that they must rely on effective supply chains, or networks, to compete in the global market and networked economy.[23] In Peter Drucker's (1998) new management paradigms, this concept of business relationships extends beyond traditional enterprise boundaries and seeks to organize entire business processes throughout a value chain of multiple companies.

In recent decades, globalization, outsourcing, and information technology have enabled many organizations, such as Dell and Hewlett Packard, to successfully operate collaborative supply networks in which each specialized business partner focuses on only a few key strategic activities.[24] This inter-organisational supply network can be acknowledged as a new form of organisation. However, with the complicated interactions among the players, the network structure fits neither "market" nor "hierarchy" categories.[25] It is not clear what kind of performance impacts different supply-network structures could have on firms, and little is known about the coordination conditions and trade-offs that may exist among the players. From a systems perspective, a complex network structure can be decomposed into individual component firms.[26] Traditionally, companies in a supply network concentrate on the inputs and outputs of the processes, with little concern for the internal management working of other individual players. Therefore, the choice of an internal management control structure is known to impact local firm performance.[27]

In the 21st century, changes in the business environment have contributed to the development of supply-chain networks. First, as an outcome of globalization and the proliferation of multinational companies, joint ventures, strategic alliances, and business partnerships, significant success factors were identified, complementing the earlier "just-in-time", lean manufacturing, and agile manufacturing practices.[28][29][30][31] Second, technological changes, particularly the dramatic fall in communication costs (a significant component of transaction costs), have led to changes in coordination among the members of the supply chain network.[32]

Many researchers have recognized supply network structures as a new organisational form, using terms such as "Keiretsu", "Extended Enterprise", "Virtual Corporation", "Global Production Network", and "Next Generation Manufacturing System".[33][34][35] In general, such a structure can be defined as "a group of semi-independent organisations, each with their capabilities, which collaborate in ever-changing constellations to serve one or more markets in order to achieve some business goal specific to that collaboration".[36]

The importance of supply chain management proved crucial in the 2019-2020 fight against the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic that swept across the world. During the pandemic period, governments in countries which had in place effective domestic supply chain management had enough medical supplies to support their needs and enough to donate their surplus to front-line health workers in other jurisdictions.[37][38][39] Some organizations were able to quickly develop foreign supply chains in order to import much needed medical supplies.[40][41][42]

Supply-chain management is also important for organizational learning. Firms with geographically more extensive supply chains connecting diverse trading cliques tend to become more innovative and productive.[43]

The security-management system for supply chains is described in ISO/IEC 28000 and ISO/IEC 28001 and related standards published jointly by the ISO and the IEC. Supply-Chain Management draws heavily from the areas of operations management, logistics, procurement, and information technology, and strives for an integrated approach.

Historical developments

Six major movements can be observed in the evolution of supply-chain management studies: creation, integration, and globalization,[44] specialization phases one and two, and SCM 2.0.

Creation era

The term "supply chain management" was first coined by Keith Oliver in 1982. However, the concept of a supply chain in management was of great importance long before, in the early 20th century, especially with the creation of the assembly line. The characteristics of this era of supply-chain management include the need for large-scale changes, re-engineering, downsizing driven by cost reduction programs, and widespread attention to Japanese management practices. However, the term became widely adopted after the publication of the seminal book Introduction to Supply Chain Management in 1999 by Robert B. Handfield and Ernest L. Nichols, Jr.,[45] which published over 25,000 copies and was translated into Japanese, Korean, Chinese, and Russian.[46]

Integration era

This era of supply-chain-management studies was highlighted with the development of electronic data interchange (EDI) systems in the 1960s, and developed through the 1990s by the introduction of enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. This era has continued to develop into the 21st century with the expansion of Internet-based collaborative systems. This era of supply-chain evolution is characterized by both increasing value added and reducing costs through integration.

A supply chain can be classified as a stage 1, 2 or 3 network. In a stage 1–type supply chain, systems such as production, storage, distribution, and material control are not linked and are independent of each other. In a stage 2 supply chain, these are integrated under one plan and enterprise resource planning (ERP) is enabled. A stage 3 supply chain is one that achieves vertical integration with upstream suppliers and downstream customers. An example of this kind of supply chain is Tesco.

Globalization era

It is the third movement of supply-chain-management development, the globalization era, can be characterized by the attention given to global systems of supplier relationships and the expansion of supply chains beyond national boundaries and into other continents. Although the use of global sources in organisations' supply chains can be traced back several decades (e.g., in the oil industry), it was not until the late 1980s that a considerable number of organizations started to integrate global sources into their core business. This era is characterized by the globalization of supply-chain management in organizations with the goal of increasing their competitive advantage, adding value, and reducing costs through global sourcing.

Specialization era (phase I): outsourced manufacturing and distribution

In the 1990s, companies began to focus on "core competencies" and specialization. They abandoned vertical integration, sold off non-core operations, and outsourced those functions to other companies. This changed management requirements, as the supply chain extended beyond the company walls and management was distributed across specialized supply-chain partnerships.

This transition also refocused the fundamental perspectives of each organization. Original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) became brand owners that required visibility deep into their supply base. They had to control the entire supply chain from above, instead of from within. Contract manufacturers had to manage bills of material with different part-numbering schemes from multiple OEMs and support customer requests for work-in-process visibility and vendor-managed inventory (VMI).

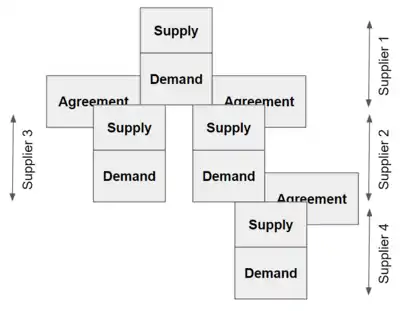

The specialization model creates manufacturing and distribution networks composed of several individual supply chains specific to producers, suppliers, and customers that work together to design, manufacture, distribute, market, sell, and service a product. This set of partners may change according to a given market, region, or channel, resulting in a proliferation of trading partner environments, each with its own unique characteristics and demands.

Specialization era (phase II): supply-chain management as a service

Specialization within the supply chain began in the 1980s with the inception of transportation brokerages, warehouse management (storage and inventory), and non-asset-based carriers, and has matured beyond transportation and logistics into aspects of supply planning, collaboration, execution, and performance management.

Market forces sometimes demand rapid changes from suppliers, logistics providers, locations, or customers in their role as components of supply-chain networks. This variability has significant effects on supply-chain infrastructure, from the foundation layers of establishing and managing electronic communication between trading partners, to more complex requirements such as the configuration of processes and work flows that are essential to the management of the network itself.

Supply-chain specialization enables companies to improve their overall competencies in the same way that outsourced manufacturing and distribution has done; it allows them to focus on their core competencies and assemble networks of specific, best-in-class partners to contribute to the overall value chain itself, thereby increasing overall performance and efficiency. The ability to quickly obtain and deploy this domain-specific supply-chain expertise without developing and maintaining an entirely unique and complex competency in house is a leading reason why supply-chain specialization is gaining popularity.

Outsourced technology hosting for supply-chain solutions debuted in the late 1990s and has taken root primarily in transportation and collaboration categories. This has progressed from the application service provider (ASP) model from roughly 1998 through 2003, to the on-demand model from approximately 2003 through 2006, to the software as a service (SaaS) model currently in focus today.

Supply-chain management 2.0 (SCM 2.0)

Building on globalization and specialization, the term "SCM 2.0" has been coined to describe both changes within supply chains themselves as well as the evolution of processes, methods, and tools to manage them in this new "era". The growing popularity of collaborative platforms is highlighted by the rise of TradeCard's supply-chain-collaboration platform, which connects multiple buyers and suppliers with financial institutions, enabling them to conduct automated supply-chain finance transactions.[47]

Web 2.0 is a trend in the use of the World Wide Web that is meant to increase creativity, information sharing, and collaboration among users. At its core, the common attribute of Web 2.0 is to help navigate the vast information available on the Web in order to find what is being bought. It is the notion of a usable pathway. SCM 2.0 replicates this notion in supply chain operations. It is the pathway to SCM results, a combination of processes, methodologies, tools, and delivery options to guide companies to their results quickly as the complexity and speed of the supply-chain increase due to global competition; rapid price fluctuations; changing oil prices; short product life cycles; expanded specialization; near-, far-, and off-shoring; and talent scarcity.

Business-process integration

Successful SCM requires a change from managing individual functions to integrating activities into key supply-chain processes. In an example scenario, a purchasing department places orders as its requirements become known. The marketing department, responding to customer demand, communicates with several distributors and retailers as it attempts to determine ways to satisfy this demand. Information shared between supply-chain partners can only be fully leveraged through process integration.

Supply-chain business-process integration involves collaborative work between buyers and suppliers, joint product development, common systems, and shared information. According to Lambert and Cooper (2000), operating an integrated supply chain requires a continuous information flow. However, in many companies, management has concluded that optimizing product flows cannot be accomplished without implementing a process approach. The key supply-chain processes stated by Lambert (2004)[48] are:

- Customer-relationship management

- Customer-service management

- Demand-management style

- Order fulfillment

- Manufacturing-flow management

- Supplier-relationship management

- Product development and commercialization

- Returns management

Much has been written about demand management.[49] Best-in-class companies have similar characteristics, which include the following:

- Internal and external collaboration

- Initiatives to reduce lead time

- Tighter feedback from customer and market demand

- Customer-level forecasting

One could suggest other critical supply business processes that combine these processes stated by Lambert, such as:

- Customer service management process

- Customer relationship management concerns the relationship between an organization and its customers. Customer service is the source of customer information. It also provides the customer with real-time information on scheduling and product availability through interfaces with the company's production and distribution operations. Successful organizations use the following steps to build customer relationships:

- determine mutually satisfying goals for organization and customers

- establish and maintain customer rapport

- induce positive feelings in the organization and the customers

- Inventory management

- Inventory management is concerned with ensuring the right stock at the right levels, in the right place, at the right time and the right cost. Inventory management entails inventory planning and forecasting: forecasting helps planning inventory.

- Procurement process

- Strategic plans are drawn up with suppliers to support the manufacturing flow management process and the development of new products.[50] In firms whose operations extend globally, sourcing may be managed on a global basis. The desired outcome is a relationship where both parties benefit and a reduction in the time required for the product's design and development. The purchasing function may also develop rapid communication systems, such as electronic data interchange (EDI) and internet linkage, to convey possible requirements more rapidly. Activities related to obtaining products and materials from outside suppliers involve resource planning, supply sourcing, negotiation, order placement, inbound transportation, storage, handling, and quality assurance, many of which include the responsibility to coordinate with suppliers on matters of scheduling, supply continuity (inventory), hedging, and research into new sources or programs. Procurement has recently been recognized as a core source of value, driven largely by the increasing trends to outsource products and services, and the changes in the global ecosystem requiring stronger relationships between buyers and sellers.[51]

- Product development and commercialization

- Here, customers and suppliers must be integrated into the product development process in order to reduce the time to market. As product life cycles shorten, the appropriate products must be developed and successfully launched with ever-shorter time schedules in order for firms to remain competitive. According to Lambert and Cooper (2000), managers of the product development and commercialization process must:

- coordinate with customer relationship management to identify customer-articulated needs;

- select materials and suppliers in conjunction with procurement; and

- develop production technology in manufacturing flow to manufacture and integrate into the best supply chain flow for the given combination of product and markets.

Integration of suppliers into the new product development process was shown to have a major impact on product target cost, quality, delivery, and market share. Tapping into suppliers as a source of innovation requires an extensive process characterized by development of technology sharing, but also involves managing intellectual[52] property issues.

- Manufacturing flow management process

- The manufacturing process produces and supplies products to the distribution channels based on past forecasts. Manufacturing processes must be flexible in order to respond to market changes and must accommodate mass customization. Orders are processes operating on a just-in-time (JIT) basis in minimum lot sizes. Changes in the manufacturing flow process lead to shorter cycle times, meaning improved responsiveness and efficiency in meeting customer demand. This process manages activities related to planning, scheduling, and supporting manufacturing operations, such as work-in-process storage, handling, transportation, and time phasing of components, inventory at manufacturing sites, and maximum flexibility in the coordination of geographical and final assemblies postponement of physical distribution operations.

- Physical distribution

- This concerns the movement of a finished product or service to customers. In physical distribution, the customer is the final destination of a marketing channel, and the availability of the product or service is a vital part of each channel participant's marketing effort. It is also through the physical distribution process that the time and space of customer service become an integral part of marketing. Thus it links a marketing channel with its customers (i.e., it links manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers).

- Outsourcing/partnerships

- This includes not just the outsourcing of the procurement of materials and components, but also the outsourcing of services that traditionally have been provided in-house. The logic of this trend is that the company will increasingly focus on those activities in the value chain in which it has a distinctive advantage and outsource everything else. This movement has been particularly evident in logistics, where the provision of transport, storage, and inventory control is increasingly subcontracted to specialists or logistics partners. Also, managing and controlling this network of partners and suppliers requires a blend of central and local involvement: strategic decisions are taken centrally, while the monitoring and control of supplier performance and day-to-day liaison with logistics partners are best managed locally.

- Performance measurement

- Experts found a strong relationship from the largest arcs of supplier and customer integration to market share and profitability. Taking advantage of supplier capabilities and emphasizing a long-term supply-chain perspective in customer relationships can both be correlated with a firm's performance. As logistics competency becomes a critical factor in creating and maintaining competitive advantage, measuring logistics performance becomes increasingly important, because the difference between profitable and unprofitable operations becomes narrower. A.T. Kearney Consultants (1985) noted that firms engaging in comprehensive performance measurement realized improvements in overall productivity. According to experts, internal measures are generally collected and analyzed by the firm, including cost, customer service, productivity, asset measurement, and quality. External performance is measured through customer perception measures and "best practice" benchmarking.

- Warehousing management

- To reduce a company's cost and expenses, warehousing management is concerned with storage, reducing manpower cost, dispatching authority with on time delivery, loading & unloading facilities with proper area, inventory management system etc.

- Workflow management

- Integrating suppliers and customers tightly into a workflow (or business process) and thereby achieving an efficient and effective supply chain is a key goal of workflow management.

Theories

There are gaps in the literature on supply-chain management studies at present (2015): there is no theoretical support for explaining the existence or the boundaries of supply-chain management. A few authors, such as Halldorsson et al.,[53] Ketchen and Hult (2006),[54] and Lavassani et al. (2009), have tried to provide theoretical foundations for different areas related to supply chain by employing organizational theories, which may include the following:

- Resource-based view (RBV)[55]

- Transaction cost analysis (TCA)

- Knowledge-based view (KBV)

- Strategic choice theory (SCT)

- Agency theory (AT)

- Channel coordination

- Institutional theory (InT)

- Systems theory (ST)

- Network perspective (NP)

- Materials logistics management (MLM)

- Just-in-time (JIT)

- Material requirements planning (MRP)

- Theory of constraints (TOC)

- Total quality management (TQM)

- Agile manufacturing

- Time-based competition (TBC)

- Quick response manufacturing (QRM)

- Customer relationship management (CRM)

- Requirements chain management (RCM)

- Dynamic Capabilities Theory

- Dynamic Management Theory

- Available-to-promise (ATP)

- Supply Chain Roadmap[56]

- Optimal Positioning of the Delivery Window (OPDW)[57][58]

However, the unit of analysis of most of these theories is not the supply chain but rather another system, such as the firm or the supplier-buyer relationship. Among the few exceptions is the relational view, which outlines a theory for considering dyads and networks of firms as a key unit of analysis for explaining superior individual firm performance (Dyer and Singh, 1998).[59]

Organization and governance

The management of supply chains involve a number of specific challenges regarding the organization of relationships among the different partners along the value chain. Formal and informal governance mechanisms are central elements in the management of supply chain.[60] Research in supply chain management has noted the importance of using the appropriate combination of contracts and relational norms to mitigate the risks and prevent conflicts between supply chain partners.[61] In turn, particular combinations of governance mechanisms may impact the relational dynamics within the supply chain.

Supply chain centroids

In the study of supply-chain management, the concept of centroids has become a useful economic consideration. In mathematics and physics, a centroid is the arithmetic mean position of all the points in a plane figure.[62] For supply chain management, a centroid is a location with a high proportion of a country's population and a high proportion of its manufacturing, generally within 500 mi (805 km). In the US, two major supply chain centroids have been defined, one near Dayton, Ohio, and a second near Riverside, California.

The centroid near Dayton is particularly important because it is closest to the population center of the US and Canada. Dayton is within 500 miles of 60% of the US population and manufacturing capacity, as well as 60% of Canada's population.[63] The region includes the interchange between I-70 and I-75, one of the busiest in the nation, with 154,000 vehicles passing through per day, of which 30–35% are trucks hauling goods. In addition, the I-75 corridor is home to the busiest north-south rail route east of the Mississippi River.[63]

A supply chain is the network of all the individuals, organizations, resources, activities and technology involved in the creation and sale of a product. A supply chain encompasses everything from the delivery of source materials from the supplier to the manufacturer through to its eventual delivery to the end user. The supply chain segment involved with getting the finished product from the manufacturer to the consumer is known as the distribution channel.[64]

Wal-Mart strategic sourcing approaches

In 2010, Wal-Mart announced a big change in its sourcing strategy. Initially, Wal-Mart relied on intermediaries in the sourcing process. It bought only 20% of its stock directly, but the rest were bought through the intermediaries.[65] Therefore, the company came to realize that the presence of many intermediaries in the product sourcing was actually increasing the costs in the supply chain. To cut these costs, Wal-Mart decided to do away with intermediaries in the supply chain and started direct sourcing of its goods from the suppliers. Eduardo Castro-Wright, the then Vice President of Wal-Mart, set an ambitious goal of buying 80% of all Wal-Mart goods directly from the suppliers.[66] Walmart started purchasing fruits and vegetables on a global scale, where it interacted directly with the suppliers of these goods. The company later engaged the suppliers of other goods, such as cloth and home electronics appliances, directly and eliminated the importing agents. The purchaser, in this case Wal-Mart, can easily direct the suppliers on how to manufacture certain products so that they can be acceptable to the consumers.[67] Thus, Wal-Mart, through direct sourcing, manages to get the exact product quality as it expects, since it engages the suppliers in the producing of these products, hence quality consistency.[66] Using agents in the sourcing process in most cases lead to inconsistency in the quality of the products, since the agent's source the products from different manufacturers that have varying qualities.

Wal-Mart managed to source directly 80% profit its stock; this has greatly eliminated the intermediaries and cut down the costs between 5-15%, as markups that are introduced by these middlemen in the supply chain are cut. This saves approximately $4–15 billion.[65] This strategy of direct sourcing not only helped Wal-Mart in reducing the costs in the supply chain but also helped in the improvement of supply chain activities through boosting efficiency throughout the entire process. In other words, direct sourcing reduced the time that takes the company to source and stocks the products in its stock.[66] The presence of the intermediaries elongated the time in the process of procurement, which sometimes led to delays in the supply of the commodities in the stores, thus, customers finding empty shelves. Wal-Mart adopted this strategy of sourcing through centralizing the entire process of procurement and sourcing by setting up four global merchandising points for general goods and clothing. The company instructed all the suppliers to bring their products to these central points that are located in different markets.[67] The procurement team assesses the quality brought by the suppliers, buys the goods, and distributes them to various regional markets. The procurement and sourcing at centralized places helped the company to consolidate the suppliers.

The company has established four centralized points, including an office in Mexico City and Canada. Just a mere piloting test on combining the purchase of fresh apples across the United States, Mexico, and Canada led to the savings of about 10%. As a result, the company intended to increase centralization of its procurement in North America for all its fresh fruits and vegetables.[65] Thus, centralization of the procurement process to various points where the suppliers would be meeting with the procurement team is the latest strategy which the company is implementing, and signs show that this strategy is going to cut costs and also improve the efficiency of the procumbent process.

Strategic vendor partnerships is another strategy the company is using in the sourcing process. Wal-Mart realized that in order for it to ensure consistency in the quality of the products it offers to the consumers and also maintain a steady supply of goods in its stores at a lower cost, it had to create strategic vendor partnerships with the suppliers.[65] Wal-Mart identified and selected the suppliers who met its demand and at the same time offered it the best prices for the goods. It then made a strategic relationship with these vendors by offering and assuring the long-term and high volume of purchases in exchange for the lowest possible prices.[66] Thus, the company has managed to source its products from same suppliers as bulks, but at lower prices. This enables the company to offer competitive prices for its products in its stores, hence, maintaining a competitive advantage over its competitors whose goods are a more expensive in comparison.

Another sourcing strategy Wal-Mart uses is implementing efficient communication relationships with the vendor networks; this is necessary to improve the material flow. The company has all the contacts with the suppliers whom they communicate regularly and make dates on when the goods would be needed, so that the suppliers get ready to deliver the goods in time.[68] The efficient communication between the company's procurement team and the inventory management team enables the company to source goods and fill its shelves on time, without causing delays and empty shelves.[69] In other words, the company realized that in ensuring a steady flow of the goods into the store, the suppliers have to be informed early enough, so that they can act accordingly to avoid delays in the delivery of goods.[66] Thus, efficient communication is another tool which Wal-Mart is using to make the supply chain be more efficient and to cut costs.

Cross-docking is another strategy that Wal-Mart is using to cut costs in its supply chain. Cross-docking is the process of transferring goods directly from inbound trucks to outbound trucks.[65] When the trucks from the suppliers arrive at the distribution centers, most of the trucks are not offloaded to keep the goods in the distribution centers or warehouses; they are transferred directly to another truck designated to deliver goods to specific retail stores for sale. Cross-docking helps in saving the storage costs.[70] Initially, the company was incurring considerable costs of storing the suppliers from the suppliers in its warehouses and the distributions centers to await the distribution trucks to the retail stores in various regions.

Tax-efficient supply-chain management

Tax-efficient supply-chain management is a business model that considers the effect of tax in the design and implementation of supply-chain management. As the consequence of globalization, cross-national businesses pay different tax rates in different countries. Due to these differences, they may legally optimize their supply chain and increase profits based on tax efficiency.[71]

Sustainability and social responsibility in supply chains

Supply chain networks are the veins of an economy, but the health of these veins is dependent on the well-being of the environment and society.[72] Supply-chain sustainability is a business issue affecting an organization's supply chain or logistics network, and is frequently quantified by comparison with SECH ratings, which uses a triple bottom line incorporating economic, social, and environmental aspects.[73] SECH ratings are defined as social, ethical, cultural, and health' footprints. Consumers have become more aware of the environmental impact of their purchases and companies' SECH ratings and, along with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), are setting the agenda for transitions to organically grown foods, anti-sweatshop labor codes, and locally produced goods that support independent and small businesses. Because supply chains may account for over 75% of a company's carbon footprint, many organizations are exploring ways to reduce this and thus improve their SECH rating.

For example, in July 2009, Wal-Mart announced its intentions to create a global sustainability index that would rate products according to the environmental and social impacts of their manufacturing and distribution. The index is intended to create environmental accountability in Wal-Mart's supply chain and to provide motivation and infrastructure for other retail companies to do the same.[74]

It has been reported that companies are increasingly taking environmental performance into account when selecting suppliers. A 2011 survey by the Carbon Trust found that 50% of multinationals expect to select their suppliers based upon carbon performance in the future and 29% of suppliers could lose their places on 'green supply chains' if they do not have adequate performance records on carbon.[75]

The US Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, signed into law by President Obama in July 2010, contained a supply chain sustainability provision in the form of the Conflict Minerals law. This law requires SEC-regulated companies to conduct third party audits of their supply chains in order to determine whether any tin, tantalum, tungsten, or gold (together referred to as conflict minerals) is mined or sourced from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and create a report (available to the general public and SEC) detailing the due diligence efforts taken and the results of the audit. The chain of suppliers and vendors to these reporting companies will be expected to provide appropriate supporting information.

Incidents like the 2013 Savar building collapse with more than 1,100 victims have led to widespread discussions about corporate social responsibility across global supply chains. Wieland and Handfield (2013) suggest that companies need to audit products and suppliers and that supplier auditing needs to go beyond direct relationships with first-tier suppliers. They also demonstrate that visibility needs to be improved if supply cannot be directly controlled and that smart and electronic technologies play a key role to improve visibility. Finally, they highlight that collaboration with local partners, across the industry and with universities is crucial to successfully managing social responsibility in supply chains.[76]

Circular supply-chain management

Circular Supply-Chain Management (CSCM) is "the configuration and coordination of the organisational functions marketing, sales, R&D, production, logistics, IT, finance, and customer service within and across business units and organizations to close, slow, intensify, narrow, and dematerialise material and energy loops to minimise resource input into and waste and emission leakage out of the system, improve its operative effectiveness and efficiency and generate competitive advantages". By reducing resource input and waste leakage along the supply chain and configure it to enable the recirculation of resources at different stages of the product or service lifecycle, potential economic and environmental benefits can be achieved. These comprise e.g. a decrease in material and waste management cost and reduced emissions and resource consumption.[77]

Components

Management components

SCM components are the third element of the four-square circulation framework. The level of integration and management of a business process link is a function of the number and level of components added to the link.[78][79] Consequently, adding more management components or increasing the level of each component can increase the level of integration of the business process link.

Literature on business process reengineering,[80][81][82] buyer-supplier relationships,[83][84][85][86] and SCM[21][87][88] suggests various possible components that should receive managerial attention when managing supply relationships. Lambert and Cooper (2000) identified the following components:

- Planning and control

- Work structure

- Organization structure

- Product flow facility structure

- Information flow facility structure

- Management methods

- Power and leadership structure

- Risk and reward structure

- Culture and attitude

However, a more careful examination of the existing literature[26][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96] leads to a more comprehensive understanding of what should be the key critical supply chain components, or "branches" of the previously identified supply chain business processes—that is, what kind of relationship the components may have that are related to suppliers and customers. Bowersox and Closs (1996) state that the emphasis on cooperation represents the synergism leading to the highest level of joint achievement. A primary-level channel participant is a business that is willing to participate in responsibility for inventory ownership or assume other financial risks, thus including primary level components.[97] A secondary-level participant (specialized) is a business that participates in channel relationships by performing essential services for primary participants, including secondary level components, which support primary participants. Third-level channel participants and components that support primary-level channel participants and are the fundamental branches of secondary-level components may also be included.

Consequently, Lambert and Cooper's framework of supply chain components does not lead to any conclusion about what are the primary- or secondary-level (specialized) supply chain components[98] —that is, which supply chain components should be viewed as primary or secondary, how these components should be structured in order to achieve a more comprehensive supply chain structure, and how to examine the supply chain as an integrative one.

Reverse supply chain

Reverse logistics is the process of managing the return of goods and may be considered as an aspect of "aftermarket customer services".[99] Any time money is taken from a company's warranty reserve or service logistics budget, one can speak of a reverse logistics operation. Reverse logistics also includes the process of managing the return of goods from store, which the returned goods are sent back to warehouse and after that either warehouse scrap the goods or send them back to supplier for replacement depending on the warranty of the merchandise.

Digitizing supply chains

Consultancies and media expect the performance efficacy of digitizing supply chains to be high.[100] Additive manufacturing and blockchain technology have emerged as the two technologies with some of the highest economic relevance. The potential of additive manufacturing is particularly high in the production of spare parts, since its introduction can reduce warehousing costs of slowly rotating spare parts.[101] Digitizing technology bears the potential to completely disrupt and restructure supply chains and enhance existing production routes.[102]

In comparison, research on the influence of blockchain technology on the supply chain is still in its early stages. The conceptual literature has argued for a considerably long time that the highest performance efficacy is expected in the potential for automatic contract creation.[103] Empirical evidence contradicts this hypothesis: the highest potential is expected in the arenas of verified customer reviews and certifications of product quality and standards.[104]

In addition, the technological features of blockchains support transparency and traceability of information, as well as high levels of reliability and immutability of records.[105] Blockchains thus offer opportunities to foster collaboration in the supply chain.[106]

Systems and value

Supply chain systems configure value for those that organize the networks. Value is the additional revenue over and above the costs of building the network. Co-creating value and sharing the benefits appropriately to encourage effective participation is a key challenge for any supply system. Tony Hines defines value as follows: "Ultimately it is the customer who pays the price for service delivered that confirms value and not the producer who simply adds cost until that point".[19]

Global applications

Global supply chains pose challenges regarding both quantity and value. Supply and value chain trends include:

- Globalization

- Increased cross-border sourcing

- Collaboration for parts of value chain with low-cost providers

- Shared service centers for logistical and administrative functions

- Increasingly global operations, which require increasingly global coordination and planning to achieve global optimums

- Complex problems involve also midsized companies to an increasing degree

These trends have many benefits for manufacturers because they make possible larger lot sizes, lower taxes, and better environments (e.g., culture, infrastructure, special tax zones, or sophisticated OEM) for their products. There are many additional challenges when the scope of supply chains is global. This is because with a supply chain of a larger scope, the lead time is much longer, and because there are more issues involved, such as multiple currencies, policies, and laws. The consequent problems include different currencies and valuations in different countries, different tax laws, different trading protocols, vulnerability to natural disasters and cyber threats,[107] and lack of transparency of cost and profit.

Roles and responsibilities

Supply chain professionals play major roles in the design and management of supply chains. In the design of supply chains, they help determine whether a product or service is provided by the firm itself (insourcing) or by another firm elsewhere (outsourcing). In the management of supply chains, supply chain professionals coordinate production among multiple providers, ensuring that production and transport of goods happen with minimal quality control or inventory problems. One goal of a well-designed and maintained supply chain for a product is to successfully build the product at minimal cost. Such a supply chain could be considered a competitive advantage for a firm.[108][109]

Beyond design and maintenance of a supply chain itself, supply chain professionals participate in aspects of business that have a bearing on supply chains, such as sales forecasting, quality management, strategy development, customer service, and systems analysis. Production of a good may evolve over time, rendering an existing supply chain design obsolete. Supply chain professionals need to be aware of changes in production and business climate that affect supply chains and create alternative supply chains as the need arises.[108]

In a research project undertaken by Michigan State University's Broad College of Business, with input from 50 participating organisations, the main issues of concern to supply chain managers were identified as capacity/resource availability, talent (recruitment), complexity, threats/challenges (supply chain risks), compliance and cost/purchasing issues. Keeping up with frequent changes in regulation was identified as a particular concern.[110]

Supply-chain consultants may provide expert knowledge in order to assess the productivity of a supply-chain and, ideally, to enhance its productivity. Supply chain consulting involves the transfer of knowledge on how to exploit existing assets through improved coordination and can hence be a source of competitive advantage: the role of the consultant is to help management by adding value to the whole process through the various sectors from the ordering of the raw materials to the final product.[111] In this regard, firms may either build internal teams of consultants to tackle the issue or engage external ones: companies choose between these two approaches taking into consideration various factors.[112]

The use of external consultants is a common practice among companies.[113] The whole consulting process generally involves the analysis of the entire supply-chain process, including the countermeasures or correctives to take to achieve a better overall performance.[114]

Certification

Individuals working in supply-chain management can attain a professional certification by passing an exam developed by a third party certification organization. The purpose of certification is to guarantee a certain level of expertise in the field.

Skills and competencies

Supply chain professionals need to have knowledge of managing supply chain functions such as transportation, warehousing, inventory management, and production planning. In the past, supply chain professionals emphasized logistics skills, such as knowledge of shipping routes, familiarity with warehousing equipment and distribution center locations and footprints, and a solid grasp of freight rates and fuel costs. More recently, supply-chain management extends to logistical support across firms and management of global supply chains.[115] Supply chain professionals need to have an understanding of business continuity basics and strategies.[116]

Education

The knowledge needed to pass a certification exam may be gained from several sources. Some knowledge may come from college courses, but most of it is acquired from a mix of on-the-job learning experiences, attending industry events, learning best practices with their peers, and reading books and articles in the field.[117] Certification organizations may provide certification workshops tailored to their exams.[118] There are also free websites that provide a significant amount of educational articles, as well as blogs that are internationally recognized which provide good sources of news and updates.

University rankings

The following North American universities rank high in their master's education in the SCM World University 100 ranking, which was published in 2017 and which is based on the opinions of supply chain managers: Michigan State University, Penn State University, University of Tennessee, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Arizona State University, University of Texas at Austin and Western Michigan University. In the same ranking, the following European universities rank high: Cranfield School of Management, Vlerick Business School, INSEAD, Cambridge University, Eindhoven University of Technology, London Business School and Copenhagen Business School.[119] In the 2016 Eduniversal Best Masters Ranking Supply Chain and Logistics the following universities rank high: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, KEDGE Business School, Purdue University, Rotterdam School of Management, Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Vienna University of Economics and Business and Copenhagen Business School.[120]

Organizations

A number of organizations provide certification in supply chain management, such as the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP),[121] IIPMR (International Institute for Procurement and Market Research), APICS (the Association for Operations Management), ISCEA (International Supply Chain Education Alliance) and IoSCM (Institute of Supply Chain Management). APICS' certification is called Certified Supply Chain Professional, or CSCP, and ISCEA's certification is called the Certified Supply Chain Manager (CSCM), CISCM (Chartered Institute of Supply Chain Management) awards certificate as Chartered Supply Chain Management Professional (CSCMP). Another, the Institute for Supply Management, is developing one called the Certified Professional in Supply Management (CPSM) [122] focused on the procurement and sourcing areas of supply-chain management. The Supply Chain Management Association (SCMA) is the main certifying body for Canada with the designations having global reciprocity. The designation Supply Chain Management Professional (SCMP) is the title of the supply chain leadership designation.

Topics addressed by selected professional supply chain certification programmes

The following table compares topics addressed by selected professional supply chain certification programmes.[122]

| Awarding Body | Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply (CIPS) | Supply Chain Management Association (SCMA) Supply Chain Management Professional (SCMP) | International Institute for Procurement and Market Research (IIPMR) Certified Supply Chain Specialist (CSCS) and Certified Procurement Professional (CPP) | Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Certified Professional in Supply Management (CPSM) | The Association for Operations Management (APICS) Certified Supply Chain Professional (CSCP) | International Supply Chain Education Alliance (ISCEA) Certified Supply Chain Manager (CSCM) | American Society of Transportation and Logistics (AST&L) Certification in Transportation and Logistics (CTL) | The Association for Operations Management (APICS) Certified Production and Inventory Management (CPIM) | International Supply Chain Education Alliance (ISCEA) Certified Supply Chain Analyst (CSCA) | Institute of Supply Chain Management (IOSCM) | Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Certified Purchasing Manager (CPM) | International Supply Chain Education Alliance (ISCEA) Certified Demand Driven Planner (CDDP) | CISCM (Chartered Institute of Supply Chain Management) awards certificate as Chartered Supply Chain Management Professional (CSCMP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procurement | High | High | High | High | High | High | Low | Low | High | High | High | Low | High |

| Strategic Sourcing | High | High | High | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | |

| New Product Development | Low | High | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | |

| Production, Lot Sizing | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | High | Low | High | Low | High | High | |

| Quality | High | High | High | High | Low | Low | High | Low | High | High | High | High | |

| Lean Six Sigma | Low | High | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High | Low | |

| Inventory Management | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | |

| Warehouse Management | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | High | High | Low | Low | High | |

| Network Design | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | High | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | |

| Transportation | High | High | Low | Low | High | High | High | High | High | High | Low | High | |

| Demand Management, S&OP | Low | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | Low | High | High | |

| Integrated SCM | High | High | Low | High | High | High | Low | High | High | High | High | High | |

| CRM, Customer Service | High | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | High | High | |

| Pricing | High | High | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Yes | High | |

| Risk Management | High | High | High | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | |

| Project Management | Low | High | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | High | |

| Leadership, People Management | High | High | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | High | High | High | |

| Technology | High | High | Low | High | High | High | Low | High | High | High | High | High | |

| Theory of Constraints | High | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High | High | |

| Operational Accounting | High | High | High | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low |

See also

- Beer distribution game

- Bullwhip effect

- Calculating demand forecast accuracy

- Cold chain

- Cost to serve

- Customer-driven supply chain

- Customer-relationship management

- Demand-chain management

- Distribution

- Document automation

- Ecodesk

- Enterprise planning systems

- Enterprise resource planning

- Industrial engineering

- Information technology management

- Integrated business planning

- Inventory

- Inventory control system

- Inventory management software

- LARG SCM

- Liquid logistics

- Logistic engineering

- Logistics

- Logistics management

- Logistics Officer

- Management accounting in supply chains

- Management information system

- Master of Science in Supply Chain Management

- Military supply-chain management

- Netchain analysis

- Offshoring Research Network

- Operations management

- Order fulfillment

- Procurement

- Procurement outsourcing

- Product quality risk in supply chain

- Radio-frequency identification

- Reverse logistics

- Service management

- Software configuration management (SCM)

- Strategic information system

- Supply-chain-management software

- Supply-chain network

- Supply-chain security

- Supply chain

- Supply management

- Trade finance

- Value chain

- Value grid

- Vendor-managed inventory

- Warehouse

- Warehouse management system

- Associations

References

- cf. Andreas Wieland, Carl Marcus Wallenburg (2011): Supply-Chain-Management in stürmischen Zeiten. Berlin.

- For SCM related to services, see for example the Association of Employment and Learning Providers' Supply Chain Management Guide at aelp.org.uk published 2013, accessed 31 March 2015

- Harland, C.M. (1996) Supply Chain Management, Purchasing and Supply Management, Logistics, Vertical Integration, Materials Management and Supply Chain Dynamics. In: Slack, N (ed.) Blackwell Encyclopedic Dictionary of Operations Management. UK: Blackwell.

- "Supply Chain - School of Operations Research and Information Engineering - Cornell Engineering". www.orie.cornell.edu. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

-

"supply chain management (SCM)". APICS Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-07-19.

supply chain management[:] The design, planning, execution, control, and monitoring of supply chain activities with the objective of creating net value, building a competitive infrastructure, leveraging worldwide logistics, synchronizing supply with demand, and measuring performance globally.

- Kozlenkova, Irina V.; Hult, G. Tomas M.; Lund, Donald J.; Mena, Jeannette A.; Kekec, Pinar (2015-05-12). "The Role of Marketing Channels in Supply Chain Management". Journal of Retailing. 91 (4): 586–609. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2015.03.003. ISSN 0022-4359.

- Lam, Hugo K.S. (2018-08-03). "Doing good across organizational boundaries: Sustainable supply chain practices and firms' financial risk". International Journal of Operations & Production Management. 38 (12): 2389–2412. doi:10.1108/ijopm-02-2018-0056. ISSN 0144-3577.

- Wieland, Andreas; Handfield, Robert B.; Durach, Christian F. (2016-08-04). "Mapping the Landscape of Future Research Themes in Supply Chain Management". Journal of Business Logistics. 37 (3): 205–212. doi:10.1111/jbl.12131. hdl:10398/d2654c3f-4303-4399-81d2-9d3a89fe79dc. ISSN 0735-3766.

- "What is Supply Chain Management (SCM)? - Definition from WhatIs.com". SearchERP. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- Ravindran, Ravi; Warsing, Donald Jr. Supply chain engineering : models and applications. CRC Press. ISBN 9781138077720.

- Sadeghi, Javad; Mousavi, Seyed Mohsen; Niaki, Seyed Taghi Akhavan (2016-08-01). "Optimizing an inventory model with fuzzy demand, backordering, and discount using a hybrid imperialist competitive algorithm". Applied Mathematical Modelling. 40 (15–16): 7318–7335. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2016.03.013. ISSN 0307-904X.

- Robert B. Handfield; Ernest L. Nichols (1999). Introduction to Supply Chain Management. New York: Prentice-Hall. p. 2. ISBN 0-13-621616-1.

- Dr. Burkhardt, Rainer (1982). "Der Weg zur Integration". WirtschaftsWoche.

- David Jacoby (2009), Guide to Supply Chain Management: How Getting it Right Boosts Corporate Performance (The Economist Books), Bloomberg Press; 1st edition, ISBN 978-1576603451

- Andrew Feller, Dan Shunk, & Tom Callarman (2006). BPTrends, March 2006 - Value Chains Vs. Supply Chains

- David Blanchard (2010), Supply Chain Management Best Practices, 2nd. Edition, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 9780470531884

- Nabil Abu el Ata, Rudolf Schmandt (2016), The Tyranny of Uncertainty, Springer, ISBN 978-3662491041

- Mentzer, J.T.; et al. (2001). "Defining Supply Chain Management". Journal of Business Logistics. 22 (2): 1–25. doi:10.1002/j.2158-1592.2001.tb00001.x.

- Tony Hines (10 January 2014). Supply Chain Strategies: Demand Driven and Customer Focused. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-70396-6.

- Lambert, 2008

- Cooper, M.C., Lambert, D.M., & Pagh, J. (1997) Supply Chain Management: More Than a New Name for Logistics. The International Journal of Logistics Management Vol 8, Iss 1, pp 1–14

- Hemold, Marc; Terry, Brian (2016). Global Sourcing and Supply Management Excellence in China: Procurement Guide for Supply Experts. Springer. p. 30.

- Baziotopoulos, 2004

- Scott, 1993

- Powell, 1990

- Zhang and Dilts, 2004

- Mintzberg, 1979

- MacDuffie and Helper, 1997

- Monden, 1993

- Womack and Jones, 1996

- Gunasekaran, 1999

- Coase, 1998

- Drucker, 1998

- Tapscott, 1996

- Dilts, 1999

- Akkermans, 2001

- News; Canada (2020-04-12). "COVID-19: Alberta to donate PPE, ventilators to other provinces | National Post". Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- Staff-56, Inside Logistics Online (2020-04-13). "Alberta sharing PPE with other provinces". Inside Logistics. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- Commissioner, Office of the (2020-03-27). "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Supply Chain Update". FDA. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- "Canada building its own PPE supply chain in China". CBC News. 2020-04-13.

- Atkins-80, Emily (2020-04-03). "Keeping up: How to keep your DC moving during the pandemic". Inside Logistics. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- García-Herrero, Alicia (2020-02-17). "Epidemic tests China's supply chain dominance". European. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- Todo, Y.; Matous, P.; Inoue, H. (11 July 2016). "The strength of long ties and the weakness of strong ties: Knowledge diffusion through supply chain networks" (PDF). Research Policy. 45 (9): 1890–1906. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2016.06.008.

- Movahedi B., Lavassani K., Kumar V. (2009) Transition to B2B e-Marketplace Enabled Supply Chain: Readiness Assessment and Success Factors, The International Journal of Technology, Knowledge and Society, Volume 5, Issue 3, pp. 75–88

- Handfield, R., and Nichols, E. (1999). Introduction to Supply Chain Management. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780136216162.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "People - Poole College of Management - NC State University". www.poole.ncsu.edu. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "Trade Services and the Supply Chain" (PDF). Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- Lambert, Douglas M.Supply Chain Management: Processes, Partnerships, Performance, 3rd edition, 2008.

- "Lessons in Demand Management | Supply Chain Resource Cooperative | NC State University". 2002-09-24. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- Mirzaee, H., Naderi, B., & Pasandideh, S. H. R. (2018). A preemptive fuzzy goal programming model for generalized supplier selection and order allocation with incremental discount. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 122, 292-302.

- Chick, Gerard, and Handfield, Robert (2014), The Procurement Value Proposition: The Rise of Supply Management, London, Kogan Page

- R. Monczka, R. Handfield, D. Frayer, G. Ragatz, and T. Scannell, New Product Development: Supplier Integration Strategies for Success, Milwaukee, WI: ASQ Press, January, 2000

- Halldorsson, Arni, Herbert Kotzab & Tage Skjott-Larsen (2003). Inter-organizational theories behind Supply Chain Management – discussion and applications, In Seuring, Stefan et al. (eds.), Strategy and Organization in Supply Chains, Physica Verlag

- Ketchen Jr., G., & Hult, T.M. (2006). Bridging organization theory and supply chain management: The case of best value supply chains. Journal of Operations Management, 25(2) 573-580

- Kozlenkova, Irina V.; Samaha, Stephen A.; Palmatier, Robert W. (2014-01-01). "Resource-based theory in marketing". Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 42 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1007/s11747-013-0336-7. ISSN 0092-0703. S2CID 39997788.

- "Supply chain strategies: Which one hits the mark? – Strategy – CSCMP's Supply Chain Quarterly". www.supplychainquarterly.com. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- Tao, Liangyan; Liu, Sifeng; Xie, Naiming; Javed, Saad Ahmed (2021-02-01). "Optimal position of supply chain delivery window with risk-averse suppliers: A CVaR optimization approach". International Journal of Production Economics. 232: 107989. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107989. ISSN 0925-5273.

- Guiffrida, Alfred L.; Nagi, Rakesh (2006-07-01). "Cost characterizations of supply chain delivery performance". International Journal of Production Economics. 102 (1): 22–36. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2005.01.015. ISSN 0925-5273.

- Dyer, Jeffrey H.; Singh, Harbir (1998). "The Relational View: Cooperative Strategy and Sources of Interorganizational Competitive Advantage". The Academy of Management Review. 23 (4): 660. doi:10.2307/259056. JSTOR 259056.

- Poppo, Laura; Zenger, Todd (2002). "Do formal contracts and relational governance function as substitutes or complements?". Strategic Management Journal. 23 (8): 707–725. doi:10.1002/smj.249. ISSN 0143-2095.

- Lumineau, Fabrice; Henderson, James E. (2012). "The influence of relational experience and contractual governance on the negotiation strategy in buyer–supplier disputes" (PDF). Journal of Operations Management. 30 (5): 382–395. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2012.03.005. ISSN 1873-1317. S2CID 14193680.

- Wikipedia Foundation, Centroid, accessed 8 December 2020

- Doug Page,"Dayton Region a Crucial Hub for Supply Chain Management" Dayton Daily News, 2009-12-21.

- "What is a Supply Chain? - Definition from WhatIs.com". WhatIs.com. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- Cmuscm, 2014

- Lu, 2014

- Gilmorte, 2010

- Wisner, Leong, & Tan, 2005

- Roberts, 2002

- Gilmorte, 2010

- "What is Tax-efficient? definition and meaning". InvestorWords.com. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- Mahmoudi, Amin; Deng, Xiaopeng; Javed, Saad Ahmed; Zhang, Na. "Sustainable Supplier Selection in Megaprojects: Grey Ordinal Priority Approach". Business Strategy and the Environment. n/a (n/a). doi:10.1002/bse.2623. ISSN 1099-0836.

- Khairul Anuar Rusli, Azmawani Abd Rahman and Ho, J.A. Green Supply Chain Management in Developing Countries: A Study of Factors and Practices in Malaysia. Paper presented at the 11th International Annual Symposium on Sustainability Science and Management (UMTAS) 2012, Kuala Terengganu, 9–11 July 2012. See publication here

- "Fun Facts About the Supply Chain and Logistics That Put Cereal On Your Table". Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "Indirect carbon emissions and why they matter". Carbon Trust. 7 Nov 2011. Retrieved 28 Jan 2014.

- Andreas Wieland and Robert B. Handfield (2013): The Socially Responsible Supply Chain: An Imperative for Global Corporations. Supply Chain Management Review, Vol. 17, No. 5.

- Geissdoerfer, Martin; Morioka, Sandra Naomi; de Carvalho, Marly Monteiro; Evans, Steve (July 2018). "Business models and supply chains for the circular economy". Journal of Cleaner Production. 190: 712–721. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.159. ISSN 0959-6526. S2CID 158887458.

- Ellram and Cooper, 1990

- Houlihan, 1985

- Macneil ,1975

- Williamson, 1974

- Hewitt, 1994

- Stevens, 1989

- Ellram and Cooper, 1993

- Ellram and Cooper, 1990

- Houlihan, 1985

- Lambert et al.,1996

- Turnbull, 1990

- Vickery et al., 2003

- Hemila, 2002

- Christopher, 1998

- Joyce et al., 1997

- Bowersox and Closs, 1996

- Williamson, 1991

- Courtright et al., 1989

- Hofstede, 1978

- Bowersox and Closs, 1996

- see Bowersox and Closs, 1996, p. 93

- MBX Global, Reverse Logistics, accessed 19 August 2020

- "Supply Chain 4.0 – the next-generation digital supply chain | McKinsey". www.mckinsey.com. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- Heinen, J. Jakob; Hoberg, Kai (December 2019). "Assessing the potential of additive manufacturing for the provision of spare parts". Journal of Operations Management. 65 (8): 810–826. doi:10.1002/joom.1054. ISSN 0272-6963.

- Durach, Christian F.; Kurpjuweit, Stefan; Wagner, Stephan M. (2017-11-06). "The impact of additive manufacturing on supply chains". International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management. 47 (10): 954–971. doi:10.1108/IJPDLM-11-2016-0332. ISSN 0960-0035.

- Iansiti, Marco; Lakhani, Karim R. (2017-01-01). "The Truth About Blockchain". Harvard Business Review (January–February 2017). ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- Durach, Christian F.; Blesik, Till; Düring, Maximilian; Bick, Markus (2020-03-09). "Blockchain Applications in Supply Chain Transactions". Journal of Business Logistics: jbl.12238. doi:10.1111/jbl.12238. ISSN 0735-3766.

- Hastig, Gabriella M.; Sodhi, ManMohan S. (2020). "Blockchain for Supply Chain Traceability: Business Requirements and Critical Success Factors". Production and Operations Management. 29 (4): 935–954. doi:10.1111/poms.13147. ISSN 1059-1478.

- Lumineau, Fabrice; Wang, Wenqian; Schilke, Oliver (2020). "Blockchain Governance—A New Way of Organizing Collaborations?". Organization Science. doi:10.1287/orsc.2020.1379.

- Demrovsky, Chloe. 5 Steps to Protect Your Supply Chain From Cyber Threats. Inbound Logistics, May 4, 2017.

- Enver Yücesan, (2007) Competitive Supply Chains a Value-Based Management Perspective, PALGRAVE MACMILLAN, ISBN 9780230515673

- David Blanchard (2007), Supply Chain Management Best Practices, Wiley, ISBN 9780471781417

- Daugherty, P. et al (n.d.), Supply Chain Issues: What's Keeping Supply Chain Managers Awake at Night?, APICS Beyond the Horizon series

- S. H. Ma, Y. Lin, Supply chain management, Beijing, China, Machinery Industry Press, 2005

- Melissa Conley-Tyler, A fundamental choice: internal or external evaluation?, Evaluation Journal of Australasia, Vol. 4 (new series), Nos. 1 & 2, March/April 2005, pp. 3–11.

- Goldberg, B & Sifonis, JG 1994, Dynamic planning: the art of managing beyond tomorrow, Oxford University Press, New York

- Shuangqin Liu and Bo Wu, Study on the Supply Chain Management of Global Companies

- "Skills and Competencies That Supply Chain Professionals Will Need". www.scmr.com. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- Betty A. Kildow (2011), Supply Chain Management Guide to Business Continuity, American Management Association, ISBN 9780814416457

- Colin Scott (2011), Guide to Supply Chain Management, Springer, ISBN 9783642176753

- Carol Ptak & Chad Smith (2011), Orlicky's 3rd Edition, McGraw Hill ISBN 978-0-07-175563-4

- "University 100 - SCM World". Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "Master Supply Chain and Logistics Ranking master Supply Chain and Logistics". www.best-masters.com. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals

- David Jacoby, 2009, Guide to Supply Chain Management: How Getting it Right Boosts Corporate Performance (The Economist Books), Bloomberg Press; 1st edition, ISBN 9781576603451. Chapter 10, Organising, training and developing staff

Further reading

- Ferenc Szidarovszky and Sándor Molnár (2002) Introduction to Matrix Theory: With Applications to Business and Economics, World Scientific Publishing. Description and preview.

- FAO, 2007, Agro-industrial supply chain management: Concepts and applications. AGSF Occasional Paper 17 Rome.

- Haag, S., Cummings, M., McCubbrey, D., Pinsonneault, A., & Donovan, R. (2006), Management Information Systems For the Information Age (3rd Canadian Ed.), Canada: McGraw Hill Ryerson ISBN 0-07-281947-2

- Halldorsson, A., Kotzab, H., Mikkola, J. H., Skjoett-Larsen, T. (2007). Complementary theories to supply chain management. Supply Chain Management, Volume 12 Issue 4, 284-296.

- Hines, T. (2004). Supply chain strategies: Customer driven and customer focused. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Hopp, W. (2011). Supply Chain Science. Chicago: Waveland Press.

- Kallrath, J., Maindl, T.I. (2006): Real Optimization with SAP® APO. Springer ISBN 3-540-22561-7.

- Kaushik K.D., & Cooper, M. (2000). Industrial Marketing Management. Volume29, Issue 1, January 2000, Pages 65–83

- Kouvelis, P.; Chambers, C.; Wang, H. (2006): Supply Chain Management Research and Production and Operations Management: Review, Trends, and Opportunities. In: Production and Operations Management, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 449–469.

- Larson, P.D. and Halldorsson, A. (2004). Logistics versus supply chain management: an international survey. International Journal of Logistics: Research & Application, Vol. 7, Issue 1, 17-31.

- Simchi-Levi D., Kaminsky P., Simchi-levi E. (2007), Designing and Managing the Supply Chain, third edition, Mcgraw Hill

- Stanton, D. (2017), Supply Chain Management For Dummies, First Edition. Wiley New York. ISBN 978-1119410195