Tekufah

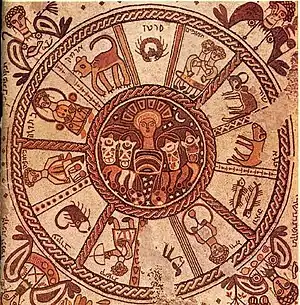

Tekufot (Hebrew: תקופות, singular: tekufah, literally, "turn" or "cycle") are the four seasons of the year recognized by Talmud writers. According to Samuel Yarḥinai, each tekufah marks the beginning of a period of 91 days 7½ hours.[1] The four tekufot are:[1]

- Tekufat Nisan, the vernal equinox, when the sun enters Aries; this is the beginning of spring, or "eit hazera" (seed-time), when day and night are equal.

- Tekufat Tammuz, the summer solstice, when the sun enters Cancer; this is the summer season, or "et ha-katsir" (harvest-time), when the day is the longest in the year.

- Tekufat Tishrei, the autumnal equinox, when the sun enters Libra, and autumn, or "et ha-batsir" (vintage-time), begins, and when the day again equals the night.

- Tekufat Tevet, the winter solstice, when the sun enters Capricornus; this is the beginning of winter, or "et ha-ḥoref" (winter-time),[2] when the night is the longest during the year.

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

|

Notice that in the early 20th century the tekufot fell from fourteen to eighteen days later than the true solar equinox or solstice.[1] However, the Jewish calendar follows the figures of R. Ada.[1]

Superstition

An ancient superstition is connected with the tekufot.[1] All water that may be in the house or stored away in vessels in the first hour of the tekufah is thrown away in the belief that the water is then poisoned, and if drunk would cause swelling of the body, sickness, and sometimes death. Several reasons are advanced for this. Some say it is because the angels who protect the water change guard at the tekufah and leave it unwatched for a short time. Others say that Cancer fights with Libra and drops blood into the water. Another authority accounts for the drops of blood in the water at Tekufat Nisan by pointing out that the waters in Egypt turned to blood at that particular moment. At Tekufat Tammuz, Moses smote the rock and caused drops of blood to flow from it. At Tekufat Tishrei the knife which Abraham held to slay Isaac dropped blood. At Tekufat Tevet, Jephthah sacrificed his daughter (Abudarham, Sha'ar ha-Tekufot, p. 122a, Venice, 1566).

The origin of the superstition cannot be traced. Hai Gaon, in the 10th century, in reply to a question as to the prevalence of this custom in the "West" (i.e., west of Babylon), said it was followed only in order that the new season might be begun with a supply of fresh, sweet water. Ibn Ezra ridicules the fear that the tekufah water will cause swelling, and ascribes the belief to the "gossip of old women" (ib.). Hezekiah da Silva, however, warns his co-religionists to pay no attention to ibn Ezra's remarks, asserting that in his own times many persons who drank water when the tekufah occurred fell ill and died in consequence. Da Silva says the principal danger lies in the first tekufah (Nisan), and a special announcement of its occurrence was made by the beadle of the congregation (Peri Ḥadash, on Oraḥ Ḥayyim, 428, end). The danger lurks only in unused water, not in water that has been boiled or used in salting or pickling. The danger in unused water may be avoided by putting in it a piece of iron or an iron vessel (Bet Yosef on the Tur, and Isserles' note to Shulḥan Aruk, Oraḥ Ḥayyim, 455, 1; Be'er Hetev, to Yore De'a, 116, 5). R. Jacob Mölln required that a new iron nail should be lowered by means of a string into the water used for baking matsot during Tekufat Nisan (Sefer Maharil, p. 6b, ed. Warsaw).

References

- "Tekufah". Jewish Encyclopedia. 1906.

- Philologos, "Stripping Down for Winter," Forward, Jan. 7, 2011, p. 11. Originally the translation in this article (copied from the article by Joseph Jacobs and Judah David Eisenstein in the Jewish Encyclopedia) read "stripping-time" which Philologos discovered was based on a misreading/mistranslation of Rabbi Levi Herzfeld who said "And so ḥoref may come from the stripping of leaves from their trees by powerful [rain] winds.

Bibliography

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Missing or empty

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Missing or empty |title=(help)