The Ebony Horse

The Ebony Horse, The Enchanted Horse or The Magic Horse[1] is a folk tale featured in the Arabian Nights. It features a flying mechanical horse, controlled using keys, that could fly into outer space and towards the Sun. The ebony horse can fly the distance of one year in a single day, and is used as a vehicle by the Prince of Persia, Qamar al-Aqmar, in his adventures across Persia, Arabia and Byzantium.[2]

| The Ebony Horse | |

|---|---|

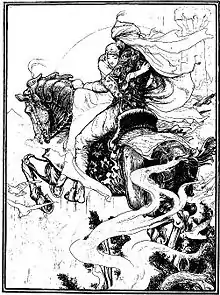

The Prince flies with the princess on the mechanical horse. Illustration by John D. Batten. | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Ebony Horse |

| Also known as | The Enchanted Horse |

| Data | |

| Aarne-Thompson grouping | ATU 575 (The Prince's Wings) |

| Published in | One Thousand and One Nights |

| Related | The Wooden Eagle (ru) |

Origin

According to researcher Ulrich Marzolph, the tale "The Ebony Horse" was part of the story repertoire of Hanna Diyab, a Christian Maronite who provided several tales to French writer Antoine Galland.[3] As per Galland's diary, the tale was told on May 13th, 1709.[4]

Summary

In the Kingdom of Persia, in the city of Schiraz, on the celebration of the New Year, an Indian arrives on a splendid horse, very much life-like, despite its mechanical and artificial appearance. The king becomes very impressed with the creature and decides to present his son, the prince, with such creation.

The young prince soon climbs the artificial ride and begins to ascend in flight. When he rises high enough, he cannot control the horse to land and departs to regions unknown. Later, he rides the flying mechanical horse to the kingdom of Bengal and meets the lovely princess, who becomes enamored with him.

The young prince retells his adventures to the princess and they both exchange sweet nothings and pleasantries, falling deeper in love still. Soon, the Persian youth convinces the Bengali princess to ride the mechanical marvel with him to his homeland of Persia.

Meanwhile, the Indian artifex had been unjustly imprisoned due to the disastrous test flight of his creation. In his cell, he sees the prince arriving with his beloved maiden. The King of Persia releases him and seizes the opportunity for revenge: he takes the horse with the princess still on it and flies into the horizon.

They soon arrive in the Kingdom of Cashmere. The king rescues the princess from Bengali and decides to marry her.

Saddened by the loss of his beloved, the Persian prince wanders until he reaches Cashmere, where he learns his maiden is alive. He then hatches a plan to escape with his beloved on the mechanical horse back to Persia.

Legacy

Scholarship points that the tale migrated to Europe and inspired similar medieval stories about a fabulous mechanical horse.[5][6] These stories include Cleomades,[7] Chaucer's The Squire's Tale,[8][9] Valentine and Orson[10] and Meliacin ou le Cheval de Fust, by troubador Girart d'Amiens (fr).[11]

Analysis

The tale is classified in Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as ATU 575, "The Prince's Wings".[12] These tales show two types of narrative:

- The first one: a metalsmith and a tinkerer take part in a contest to build a mechanical marvel to impress the king and his son. A mechanical horse is built and delivered to the king, to the delight of the young prince.

- The second one: the prince himself commissions from a skilled craftsman to fashion a winged apparatus to allow him to fly (eg. a pair of wings or a wooden bird).

The tale The Ebony Horse, in particular, was suggested by mythologist Thomas Keightley, in his book Tales and Popular Fictions, to have originated from a genuine Persian source, since it does not contain elements from Islamic religion.[13]

The oldest attestation and possible origin of the tale type is suggested to be an 11th century Jain recension of the Pancatantra, wherein a poor weaver fashions an artificial likeness of legendary bird mount Garuda, the ride of god Vishnu. He uses the construct to reach the topmost room of the princess he fell in love with and poses as Lord Vishnu to impress his beloved.[14][15][16]

Ethnologist Verrier Elwin commented that some folk tales replace the original flying machine for a trunk or a chair,[17] and that the motif of the equine machine is common in Indian folk-tales.[18]

Variants

Stith Thompson sees a sparsity of the tale in European compilations, although the elements of the prince's journey on the mechanical apparatus appear in Eastern tales.[19]

Europe

Philologist Franz Miklosich collected a variant in Romani language which he titled Der geflügelte Held ("The Flying Hero"), about an artifex that fashions a pair of wings.[20]

Germany

The Brothers Grimm also collected and published a German variant titled Vom Schreiner und Drechsler ("Of The Carpenter and The Turner"). This story was published in the first edition of their collection, in 1812, with numbering KHM 77, but omitted from the definitive edition.[21]

A variant exists in the newly discovered collection of Bavarian folk and fairy tales of Franz Xaver von Schönwerth, titled The Flying Trunk (German: Das fliegende Kästchen).[22]

In a variant collected from Oldenburg by jurist Ludwig Strackerjan (de), Vom Königssohn, der fliegen gelernt hatte ("About a King's Son who learned to fly"), each of the king's sons learn a trade: one becomes a metalsmith and the other a carpenter. The first one builds a fish of silver and the second fashions a pair of wooden wings. He later uses the wings to fly to another realm, where he convinces a sheltered princess he is the Archangel Gabriel.[23]

Italy

Ignaz and Joseph Zingerle collected a variant from Merano, titled Die zwei Künstler ("The Two Craftsmen"), wherein a goldsmith and a fortune-teller compete to see who can craft a fine work: the goldsmith some gold fishes and the fortuneteller a pair of wooden wings.[24]

Hungary

Journalist Elek Benedek collected a Hungarian tale titled A Szárnyas Királyfi ("The Winged Prince"). In this story, the king traps his daughter in the tower, but a prince visits her every night with a pair of wings.[25]

Greece

Johann Georg von Hahn collected a variant from Zagori, Greece, titled Der Mann mit der Reisekiste ("The Man with the Flying Trunk"): a rich man with an intense wanderlust commissions a flying trunk form his carpenter friend. The carpenter fills the box with "magic vapours" and the device takes flight. The rich man arrives at the tower of a princess from another realm and pretends to be the Son of God.[26]

Russia

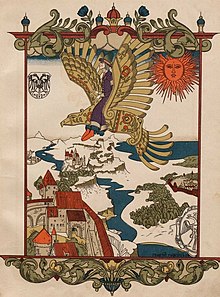

The tale type is known in Russia and Slavic-speaking regions as "Деревянный орёл" (The Wooden Eagle), after the creation that appears in the story: a wooden eagle (ru).

Another Russian variant of the tale type is Märchen von dem berühmten und ausgezeichneten Prinzen Malandrach Ibrahimowitsch und der schönen Prinzeß Salikalla or Prince Malandrach and the Princess Salikalla, a tale that first appeared in a German language compilation of fairy tales, published by Anton Dietrich in 1831, in Leipzig.[27] The titular prince becomes fascinated with the idea of flying after reading about it in a book of fairy tales. He wants to commission a pair of wooden wings from a carpenter.[28][29]

Middle East

A similar story, also named The Tale of the Ebony Horse, can also be found in One Hundred and One Nights, another book of Arab literature and whose original manuscripts were recently discovered.[30]

Andrew Lang published the story with the name The Enchanted Horse, in his translation of The Arabian Nights, and renamed the prince Firouz Schah.[31]

Folklorist William Forsell Kirby published a tale from "The Arabian Nights" titled Story of the Labourer and the Flying Chair: a poor labourer spends his earnings on an old chair. He returns to the seller wanting to know the instructions on how to use the chair. The labourer manages to control the chair, which takes him to a distant terrace. He walks from the terrace into a room where a princess was sleeping. The maiden awakes with a startle with the strange person in the room, and he presents himself as Azrael, the Angel of Death.[32]

French orientalist François Pétit de La Croix published in the 18th century a compilation of Middle Eastern tales, titled Mille et Un Jours ("The Thousand and One Days"). This compilation also contains a variant of the tale type, named Story of Malek and the Princess Schirine: the hero Malek receives a bird-shaped box from an artisan. He enters the box and flies away to a distant kingdom. In this realm, he learns of King Bahaman, who imprisoned his daughter, the Princess Schirine, in a tower.[33]

South Asia

An Indian version was published with the title The Magic Horse.[34]

Charles Swynnerton published another Indian tale titled Prince Ahmed and the Flying Horse: Prince Ahmed likes to play with the sons of a goldsmith, an ironsmith, an oilman, and a carpenter, much to his father's disgust. The king decided to imprison the four youths, but the prince, their friends, intercedes in their favour: all four should prove their skills. The four fashion, respectively, six brazen fishes, two large iron fishes, two artificial giants and at last a wooden horse. Prince Ahmed climbs the horse and flies to regions unknown, where he romances a princess and brings her back to his homeland.[35][36]

Another tale is The Wax Horse: a king hides his son from the outside world due to a prophecy that the son would go away from his kingdom. One day, the young prince sees a wax horse with wings in the market and the king buys it for him. The prince climbs on the horse and flies to another kingdom, eventually meeting a princess.[37]

In another Indian tale, Concerning a Royal Prince and a Princess, a carpenter's son fashions a Wooden Peacock, which the Prince test drives and arrives in another kingdom. He hides the Wooden Peacock in the foliages and sees a princes bathing. Later, the prince flies to her window. The princess, then, decides to hide her lover inside her room by commissioning a man-sized lamp with a secret compartment. The princess becomes pregnant and escapes with the prince to the jungle. Her royal lover gets stranded in the sea, due to the machinations of fate, and the princess is forced to raise the child on her own. She, however, gets help from an ascetic, who, by performing "an Act of Truth", creates two other children out of flowers for the maiden to rear.[38]

Literary variants

Illustrator Howard Pyle included a tale named The Stool of Fortune in his work Twilight Land, a crossover of famous fairy tale characters (Mother Goose, Cinderella, Fortunatus, Sinbad the Sailor, Aladdin, Boots, the Valiant Little Tailor) that meet in an inn to tell stories. In The Stool of Fortune, a nameless wandering soldier is hired by a magician to shoot some animals. Angry at the unjust payment, the soldier enters the magician hut and sits on a three-legged stool, waiting for his employer. Wishing he was anywhere else, the stool obeys his command and starts to fly away. The soldier then arrives at the tower room of a unsuspecting princess and announces himself as "The King of Winds".[39]

Sufi scholar Idries Shah adapted the tale as the children's book The Magic Horse: a King summons a woodcarver and a metalsmith to create wondrous contraptions. The woodcarver constructs a wooden horse, which draws the attention of the king's youngest son, prince Tambal.

Adaptations

The Russian variant of the tale type ATU 575, "The Wooden Eagle", was adapted into a Soviet animated film in 1953 (ru).

The tale type was also adapted into a Czech fantasy film in 1987, titled O princezně Jasněnce a ševci, který létal (Princess Jasnenka and the Flying Shoemaker). The film was based on a homonymous literary fairy tale by Czech author Jan Drda, first published in 1959, in České pohádky.

See also

- The Flying Trunk, literary fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen

- Flying carpet

- Pegasus, mythological flying horse

- Haizum

- Qianlima

- Hippogriff

- Tulpar

- Tianma

References

- Scull, William Ellis; Marshall, Logan (ed.). Fairy Tales of All Nations: Famous Stories from the English, German, French, Italian, Arabic, Russian, Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Bohemian, Japanese and Other Sources. Philadelphia: J. C. Winston Co. 1910. pp. 129-140.

- Marzolph, Ulrich; van Leewen, Richard. The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. Vol. I. California: ABC-Clio. 2004. pp. 172-173. ISBN 1-85109-640-X (e-book)

- Marzolph, Ulrich. "the Man Who Made the Nights Immortal: The Tales of the Syrian Maronite Storyteller Ḥannā Diyāb". In: Marvels & Tales, 32.1 (2018), 114–25 (pp. 118–19), doi:10.13110/marvelstales.32.1.0114.

- Chraïbi, Aboubakr. "Galland's "Ali Baba" and Other Arabic Versions". In: Marvels & Tales 18, no. 2 (2004): 159-69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41388705.

- Burton, Richard F. The Book of the Thousand Nights and one Night. With introduction, explanatory notes on the manners and customs of Moslem men and a terminal essay upon the history of The Nights. Volume 5. USA: Printed by the Burton Club. p. 2 (footnote nr. 5)

- Marzolph, Ulrich; van Leewen, Richard. The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. Vol. I. California: ABC-Clio. 2004. p. 174. ISBN 1-85109-640-X (e-book)

- Keightley, Thomas. Tales And Popular Fictions: Their Resemblance, And Transmission From Country to Country. London: Whittaker. 1834. pp. 40-69.

- Braddy, Haldeen. "The Oriental Origin of Chaucer's Canacee-Falcon Episode." In: The Modern Language Review 31, no. 1 (1936): 11-19. Accessed December 14, 2020. doi:10.2307/3715187.

- Chaucer, Geoffrey; Pollard, Alfred William. Canterbury tales: The squire's tale. London, New York: Macmillan. 1889. pp. xiii-xvi.

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Zweiter Band (NR. 61-120). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. p. 184 (footnote).

- Jones, H. S. V. "The Cléomadès, the Méliacin, and the Arabian Tale of the "Enchanted Horse"." In: The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 6, no. 2 (1907): 221-43. Accessed December 14, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27699843.

- Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- Keightley, Thomas. Tales And Popular Fictions: Their Resemblance, And Transmission From Country to Country. London: Whittaker. 1834. pp. 71-72.

- Hahn, Johann Georg von. Griechische und Albanesische Märchen 1-2. München/Berlin: Georg Müller. 1918 [1864]. p. 401-402.

- Burton, Richard F. The Book of the Thousand Nights and one Night. With introduction, explanatory notes on the manners and customs of Moslem men and a terminal essay upon the history of The Nights. Volume 5. USA: Printed by the Burton Club. p. 2 (footnote nr. 5)

- Marzolph, Ulrich; van Leewen, Richard. The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. Vol. I. California: ABC-Clio. 2004. pp. 173-174. ISBN 1-85109-640-X (e-book)

- Elwin, Verrier. Folk-tales of Mahakoshal. [London]: Pub. for Man in India by H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1944. p. 112.

- Elwin, Verrier. Folk-tales of Mahakoshal. [London]: Pub. for Man in India by H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1944. p. 112.

- Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. pp. 78 and 180. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- Miklosich, Franz. Über die Mundarten und die Wanderungen der Zigeuner Europa's. Volume 4. Wien: 1872. pp. 31-34.

- Grimm, Jacob, Wilhelm Grimm, JACK ZIPES, and ANDREA DEZSÖ. "THE CARPENTER AND THE TURNER." In: The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014. pp. 244-245. doi:10.2307/j.ctt6wq18v.84.

- Schönwerth. Franz Xaver von. The Turnip Princess and Other Newly Discovered Fairy Tales. Edited by Erika Eichenseer. Translated by Maria Tatar. New York: Penguin Books. 2015. pp. 14-16. ISBN 978-0-698-14455-2

- Strackerjan, Ludwig. Aberglaube und Sagen aus dem Herzogtum Oldenburg 1–2, Band 2, Oldenburg 1909. pp. 490-493.

- Zingerle, Ignaz und Joseph. Kinder- und Hausmärchen aus Süddeutschland. [Regensburg: 1854] Nachdruck München: Borowsky, 1980, pp. 45-49.

- Benedek Elek. Többsincs királyfi és más mesék. Tale nr. 24.

- Hahn, Johann Georg von. Griechische und Albanesische Märchen 1. München/Berlin: Georg Müller, 1918 [1864]. pp. 235-238.

- Dietrich, Anton. Russische Volksmärchen in den Urschriften gesammelt und ins Deutsche übersetzt. Leipzig: Weidmann'sche Buchhandlung. 1831. pp. 144-157.

- The winged wolf and other fairy tales. London: Edward Stanford. 1893. pp. 53-66.

- Steele, Robert. The Russian garland: being Russian folk tales. London: A.M. Philpot. [1916?] pp. 142-152.

- Fudge, Bruce, and Robert Irwin. A Hundred and One Nights. Edited by Kennedy Philip F. and Pomerantz Maurice. New York: NYU Press, 2017. pp. 161-180. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1pwt9sm. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1pwt9sm.25

- Lang, Andew. The Arabian Nights Entertainments. New York and Bombay: Longmans Green & Co. 1898. pp. 359-389.

- Kirby, William Forsell. The new Arabian nights. Select tales, not included by Galland or Lane. Philadelphia, J.B. Lippincott & co.. 1884. pp. 272-296.

- Pardoe, Julia. The Thousand and One Days: A Companion to the "Arabian Nights". London: William Lay. 1857. pp. 340-358.

- Thornhill, Mark. Indian fairy tales. London: Hatchards. [1888] pp. 108-145.

- Swynnerton, Charles. Indian nights' entertainment; or, Folk-tales from the Upper Indus. London: Stock. 1892. pp. 9-11.

- Swynnerton, Charles. Romantic Tales From The Panjab With Indian Nights’ Entertainment. London: Archibald Constable and Co.. 1908. pp. 157-160.

- Parker, H. Village Folk-Tales of Ceylon. Vol. III. London: Luzac and Co. 1914. pp. 193-199.

- Village Folk-Tales of Ceylon. Collected and translated by H. Parker. Vol. II. London: Luzac & Co. 1914. pp. 23-30.

- Pyle, Howard. Twilight Land. New York: Harper, 1894. pp. 5-27.

Bibliography

- Chauvin, Victor Charles. Bibliographie des ouvrages arabes ou relatifs aux Arabes, publiés dans l'Europe chrétienne de 1810 à 1885. Volume V. Líege: H. Vaillant-Carmanne. 1901. pp. 221-231.

Further reading

- Akel, Ibrahim. "Redécouverte d’un manuscrit oublié des Mille et une nuits". In: The Thousand and One Nights: Sources and Transformations in Literature, Art, and Science. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2020. pp. 57-67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004429031_005

- Bottigheimer, Ruth B. and Claudia Ott. “The Case of the Ebony Horse, part 1”. Gramarye. vol. 5, 2014, pp. 8–20.

- Bottigheimer, Ruth B. “The Case of the Ebony Horse, part 2: Hannā Diyāb’s Creation of a Third Tradition”. Gramarye, vol. 6, 2014, pp. 7–16.

- Cox, H.L. "'L'Histoire du cheval enchante" aus 1001 Nacht in der miindlichen Oberlieferung Franzosisch-Flanders". In: D. HARMENING & E. WIMMER (red.), Volkskultur - Geschichte - Region: Festschrift für Wolfgang Brückner zum 60. Geburtstag. Würzburg: Verlag Königshausen & Neumann GmbH. 1992. pp. 581-596.

- Marzolph, Ulrich. 101 Middle Eastern Tales and Their Impact on Western Oral Tradition. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2020. pp. 86-94. muse.jhu.edu/book/77103.

- Olshin, Benjamin B. "Ancient Tales of Flying Machines". In: Lost Knowledge. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2019. pp. 40-113. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004352728_003

External links

- The Enchanted Horse on Wikisource (translation by John Payne)