The Madness of King George

The Madness of King George is a 1994 British biographical historical comedy-drama film directed by Nicholas Hytner and adapted by Alan Bennett from his own 1991 play The Madness of George III. It tells the true story of George III of Great Britain's deteriorating mental health, and his equally declining relationship with his eldest son, the Prince of Wales, particularly focusing on the period around the Regency Crisis of 1788–89. Modern medicine has suggested that the King's symptoms were the result of acute intermittent porphyria, although this theory has been vigorously challenged, most notably by a research project based at St George's, University of London, which concluded that George III did actually suffer from mental illness after all.[3]

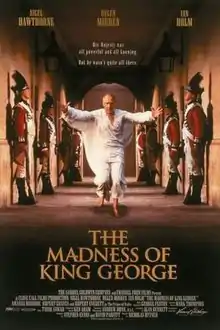

| The Madness of King George | |

|---|---|

Original theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Nicholas Hytner |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | Alan Bennett |

| Based on | The Madness of George III by Alan Bennett |

| Starring | |

| Music by | |

| Cinematography | Andrew Dunn |

| Edited by | Tariq Anwar |

| Distributed by | The Samuel Goldwyn Company |

Release date |

|

Running time | 110 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $15.2 million[2] |

The Madness of King George won the BAFTA Awards in 1995 for Outstanding British Film and Best Actor in a Leading Role for Nigel Hawthorne, who was also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor. The movie won the Oscar for Best Art Direction; and was also nominated for Oscars for Best Supporting Actress for Mirren, and Best Adapted Screenplay. Helen Mirren also won the Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Actress and Hytner was nominated for the Palme d'Or.

In 1999, the British Film Institute voted The Madness of King George the 42nd greatest British film of all time.

Plot

The film depicts the ordeal of King George III whose bout of madness in 1788 touched off the Regency Crisis of 1788, triggering a power struggle between factions of Parliament under the Tory Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger and the reform-minded Leader of the Opposition Charles James Fox.

At first, the King's habits appear mildly eccentric, and are purposely ignored for reasons of state. The King is seen as being highly concerned with the wellbeing and productivity of Great Britain, and continually exhibits an encyclopedic knowledge of the families of even the most obscure royal appointments. In fact, the King is growing more unsettled, largely over the loss of America. The King's eldest son George, Prince of Wales, aggravates the situation, knowing that he would be named regent in the event the King was found incapacitated. George chafes under his father's repeated criticism, but also hopes for regency to allow him greater freedom to marry his Catholic mistress Mrs. Fitzherbert. George also knows that he has the moral support of Fox, who is eager to put across an agenda unlikely to pass under the current administration, including abolition of the slave trade and friendlier relations with America. Knowing that the King's behaviour is exacerbated in public, the Prince arranges for a concert playing the music of Handel. The King reacts as expected, interrupting the musicians, acting inappropriately towards Lady Pembroke, Lady of the Bedchamber, and finally assaulting his son.

The King's madness is treated using the relatively primitive medical practices of the time, which include blistering and purges, led on particularly by the Prince of Wales' personal physician, Dr. Warren. Eventually, Lady Pembroke recommends Dr. Francis Willis, an ex-minister who attempts to cure the insane through new procedures, and who begins his restoration of the King's mental state by enforcing a strict regimen of strapping the King into a waistcoat and restraining him whenever he shows signs of his insanity or otherwise resists recovery.

Meanwhile, the Whig opposition led by Fox confronts Pitt's increasingly unpopular Tory government with a bill that would give the Prince powers of regency. Meanwhile, Baron Thurlow, the Lord Chancellor, discovers that the Prince was secretly and illegally married to his Catholic mistress. Thurlow pays the minister to keep his mouth shut, and himself tears out a record of the marriage from church rolls.

The King soon shows signs of recovery, becoming less eccentric and arrives in Parliament in time to thwart passage of the Regency bill. Restored, the King asserts control over his family, forcing the Prince to "put away" his mistress. With the crisis averted, those who had been closest to the King are summarily dismissed from service, including Dr. Willis. During conversations with Pitt, the King appears more at ease and in control of himself. He is less antagonized by America, but also shows signs that his insanity remains. A final message states that the King likely suffered from porphyria, noting that it is an incurable chronic condition and is hereditary.

Cast

- Nigel Hawthorne as King George III

- Helen Mirren as Queen Charlotte

- Ian Holm as Francis Willis

- Amanda Donohoe as Lady Pembroke, Lady of the Bedchamber

- Rupert Graves as Colonel Greville

- Geoffrey Palmer as Doctor Warren

- Rupert Everett as George, Prince of Wales

- Jim Carter as Charles James Fox, Leader of the Opposition

- Julian Rhind-Tutt as Frederick, the Duke of York

- Julian Wadham as William Pitt the Younger, Prime Minister

- Anthony Calf as Lord Charles FitzRoy

- Adrian Scarborough as Fortnum

- John Wood as Lord Chancellor Lord Thurlow

- Jeremy Child as Black Rod

- Struan Rodger as Henry Dundas

- Barry Stanton as Sheridan

- Janine Duvitski as Margaret Nicholson

- Caroline Harker as Mrs. Fitzherbert

- Roger Hammond as Baker

- Cyril Shaps as Pepys

- Selina Cadell as Mrs. Cordwell

- Alan Bennett as a backbench MP whose speech is interrupted by everyone running out to see the King

- Nicholas Selby as Speaker

Production

Alan Bennett insisted that director Nicholas Hytner and actor Nigel Hawthorne do the film version, after having done the play.[4][5]

Title change

In adapting the play to film, the director Nicholas Hytner changed the name from The Madness of George III to The Madness of King George for American audiences, to clarify George III's royalty. A popular explanation developed that the change was made because there was a worry that American audiences would think it was a sequel and not go to see it, assuming they had missed "I" and "II". An interview revealed: "That's not totally untrue," said Hytner, laughing. "But there was also the factor that it was felt necessary to get the word King into the title."[6]

Filming locations

Principal photography took place from 11 July to 9 September 1994. The film was shot at Shepperton Studios and on location at:

- Arundel Castle, Arundel, West Sussex

- Divinity School, Oxford

- Broughton Castle, Banbury, Oxfordshire

- Eton College, Eton, Berkshire

- Royal Naval College, Greenwich

- St. Paul's Cathedral, London

- Syon House, Brentford, Middlesex

- Thame Park, Oxfordshire

- Wilton House, Wilton, Wiltshire

Reception

Box office

The Madness of King George debuted strongly at the box office.[7] The film grossed $15,238,689 from 464 North American venues.[2]

Critical response

The film received largely positive reviews from critics. On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 93% "Certified Fresh" score based on 44 reviews, with an average rating of 7.83/10. The site's consensus states: "Thanks largely to stellar all-around performances from a talented cast, The Madness of King George is a funny, entertaining, and immensely likable adaptation of the eponymous stage production."[8]

Reviewing the film for Variety, Emanuel Levy praised the film highly, writing: "Under Hytner's guidance, the cast, composed of some of the best actors in British cinema, rises to the occasion... Boasting a rich period look, almost every shot is filled with handsome, emotionally charged composition."[9]

John Simon of The National Review wrote, "The Madness of King George III has survived the transfer from stage to screen, and emerges equally enjoyable on film." Simon praised all the leading actors and most of the supporting cast with the exception of Jim Carter's portrayal of Fox, which he said lacked charisma.[10]

Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic wrote, "For those who, like myself, were disappointed in the play, the film contains pleasant surprises, all of them resulting from differences between the two arts."[11]

Year-end lists

- 2nd – Peter Rainer, Los Angeles Times[12]

- 8th – National Board of Review[13]

- 10th – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times[12]

- Top 10 runner-ups (not ranked) – Janet Maslin, The New York Times[14]

Awards and honours

Academy Awards

- Best Actor (Nigel Hawthorne) – Nominated

- Best Supporting Actress (Helen Mirren) – Nominated

- Best Adapted Screenplay (Alan Bennett) – Nominated

- Best Art Direction (Ken Adam, Carolyn Scott) – Won

BAFTA Awards

- Best Film (David Parfitt) – Nominated

- Best British Film (David Parfitt) – Won

- Best Direction (Nicholas Hytner) – Nominated

- Best Actor in a Leading Role (Nigel Hawthorne) – Won

- Best Actress in a Leading Role (Helen Mirren) – Nominated

- Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Ian Holm) – Nominated

- Best Adapted Screenplay (Alan Bennett) – Nominated

- Best Film Music (George Fenton) – Nominated

- Best Cinematography (Andrew Dunn) – Nominated

- Best Production Design (Ken Adam) – Nominated

- Best Costume Design (Mark Thompson) – Nominated

- Best Editing (Tariq Anwar) – Nominated

- Best Sound (Christopher Ackland, David Crozier, Robin O'Donoghue) – Nominated

- Best Makeup and Hair (Lisa Westcott) – Won

Other awards and nominations

- Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Actress (Helen Mirren) – Won

- Palme d'Or (Nicholas Hytner) – Nominated[15]

- Best Actor (Nigel Hawthorne) – Won.[16]

- Evening Standard British Film Award for Best Film (Nicholas Hytner) – Won

- Evening Standard British Film Award for Best Screenplay (Alan Bennett) – Won

- Evening Standard British Film Award for Best Technical/Artistic Achievement (Andrew Dunn) – Won

- Goya Award for Best European Film (Nicholas Hytner) – Nominated

- London Film Critics' Circle Award for British Film of the Year – Won

- London Film Critics' Circle Award for British Actor of the Year (Nigel Hawthorne) – Won

- London Film Critics' Circle Award for British Actress of the Year (Helen Mirren) – Nominated

- London Film Critics' Circle Award for British Screenwriter of the Year (Alan Bennett) – Won

- London Film Critics' Circle Award for British Technical Achievement of the Year (Ken Adam) – Won

- National Board of Review: Top Ten Films – Won

- Writers Guild of America: Best Screenplay Based on Material Previously Produced or Published (Alan Bennett) – Nominated

- Writers' Guild of Great Britain: Film – Screenplay (Alan Bennett) – Won

See also

References

- "THE MADNESS OF KING GEORGE (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. 23 January 1995. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- "The Madness of King George (1994)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- What Was The Truth About The Madness Of George III?

- "The Madness of King George". EW.com.

- DAVID GRITTEN (8 January 1995). "Late-Blooming Nigel Hawthorne Enjoys 'Madness' of King-Size Role in Hytner's Film". Los Angeles Times.

“It was wonderful that Alan Bennett insisted on Nick and me doing the film after we’d done it as a play,” he said of the playwright.

- "PROFILE : Life on an Artistic Carousel : Nicholas Hytner, director of 'Miss Saigon' and 'Carousel,' and 'Madness of King George' on film, is the hottest British import. Is he ready for America's Pop Icon Machine?". LA Times. 8 January 1995. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- Natale, Richard (3 January 1995). "New Year Box Office Starts Off With Bang Movies: At $15.5 million, `Dumb' stole the show during the long holiday weekend. But many other movies filled the seats as well". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- "The Madness of King George (1994)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- Review: 'The Madness of King George'. Retrieved on 8 October 2016 from https://variety.com/1994/film/reviews/the-madness-of-king-george-2-1200439660/.

- Simon, John (2005). John Simon on Film: Criticism 1982-2001. Applause Books. pp. 450–451.

- Stanley Kauffmann at rottentomatoes.com

- Turan, Kenneth (25 December 1994). "1994: YEAR IN REVIEW : No Weddings, No Lions, No Gumps". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Awards for 1994". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Maslin, Janet (27 December 1994). "CRITIC'S NOTEBOOK; The Good, Bad and In-Between In a Year of Surprises on Film". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- "Festival de Cannes: The Madness of King George". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- "Empire Awards Past Winners - 1996". Empireonline.com. Bauer Consumer Media. 2003. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

External links

- The Madness of King George at IMDb

- The Madness of King George at Box Office Mojo

- The Madness of King George at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Madness of King George at AllMovie

- The Madness of King George at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Mikkelson, Barbara & David P. "The Madness of King George" at Snopes.com: Urban Legends Reference Pages.