Leader of the Opposition (United Kingdom)

The leader of Her Majesty's Most Loyal Opposition, more commonly known simply as the leader of the opposition, is the politician who leads the official opposition in the United Kingdom. The leader of the opposition by convention leads the largest party not within the government: where one party wins outright this is the party leader of the second largest political party in the House of Commons. The current leader of the opposition is Keir Starmer, the leader of the Labour Party, who was elected to the leadership of the Labour Party on 4 April 2020.[3]

Leader of the Official Opposition | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom | |

| Official Opposition Parliament of the United Kingdom Leader of the Opposition's Office | |

| Style | Leader of the Opposition (informal) The Right Honourable (UK and Commonwealth) |

| Member of | |

| Appointer | Largest political party not in government |

| Term length | While leader of the largest party not in government |

| Inaugural holder | The Lord Grenville |

| Formation | March 1807 1 July 1937 (Statutory) |

| Deputy | Angela Rayner |

| Salary | £144,649[1] (including £79,468 MP salary[2]) |

| Website | Her Majesty's Official Opposition: The Shadow Cabinet |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Politics of the United Kingdom |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

The leader of the opposition is normally viewed as an alternative or shadow prime minister, and is appointed to the Privy Council. They lead an Official Opposition Shadow Cabinet which scrutinises the actions of the Cabinet led by the prime minister, as well as offer alternative policies.

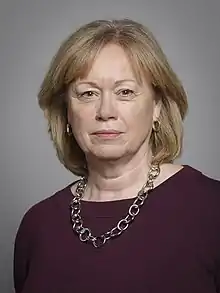

There is also a leader of the opposition in the House of Lords (currently the Baroness Smith of Basildon). In the nineteenth century party affiliations were generally less fixed and leaders in the two Houses were often of equal status. A single, clear leader of the opposition was only definitively settled if the opposition leader in Commons or Lords was the outgoing prime minister. However, since the Parliament Act 1911 there has been no dispute that the leader in the House of Commons is pre-eminent and has always held the main title.

The leader of the opposition is entitled to a salary in addition to their salary as a Member of Parliament. In 2019, this additional entitlement was available up to £65,181.[1]

Leaders of the opposition from 1807

The first modern leader of the opposition was Charles James Fox, who led the Whigs as such for a generation, except during the Fox–North Coalition in 1783. He finally rejoined the government in 1806, and died later that year.

Early developments 1807–30

For there to be a recognised leader of the opposition, it is necessary for there to be a sufficiently cohesive opposition to need a formal leader. The emergence of the office thus coincided with the period when wholly united parties (Whig and Tory, governments and oppositions) became the norm.[4] This situation was normalised in the Parliament of 1807–1812, when the members of the Grenvillite and Foxite Whig factions resolved to maintain a joint, dual-house leadership for the whole party.

The Ministry of all the Talents, in which both Whig factions participated fell at the 1807 general election, during which the Whigs had re-adopted traditional factions, forming an opposition. The prime minister of the Talents ministry, Lord Grenville had led his eponymous faction from the House of Lords. Meanwhile, the government leader of the House of Commons, Viscount Howick (later known as Earl Grey and the political heir of Charles James Fox who had died in 1806), led his faction, the Foxite whigs, from the House of Commons.[4]

Howick's father, the 1st Earl Grey died on 14 November 1807. As such the new Earl Grey vacated his seat in the House of Commons and moved to the House of Lords. This left no obvious Whig leader in the House of Commons.[4]

Grenville's article in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography confirms that he was considered the Whig leader in the House of Lords between 1807 and 1817, despite Grey leading the larger faction.

Grenville and Grey, political historian Archibald Foord describes as being "duumvirs of the party from 1807 to 1817" and consulted about what was to be done. Grenville was at first reluctant to name a leader of the opposition in the House of Commons, commenting "... all the elections in the world would not have made Windham or Sheridan leaders of the old Opposition while Fox was alive ...".

Eventually they jointly recommended George Ponsonby to the Whig MPs, whom they accepted as the first leader of the opposition in the House of Commons. Ponsonby, an Irish lawyer who was the uncle of Grey's wife, had been Lord Chancellor of Ireland during the Ministry of all the Talents and had only just been re-elected to the House of Commons in 1808 when he became leader.[4] Ponsonby proved a weak leader but as he could not be persuaded to resign and the duumvirs did not want to depose him, he remained in place until he died in 1817.[4]

Lord Grenville retired from active politics in 1817, leaving Grey as the leader of the opposition in the House of Lords. Grey was not a former prime minister in 1817, unlike Grenville, so under the convention that developed later in the century he would have been in theory of equal status to whoever was leader in the other House. However, there was little doubt that if a Whig ministry was possible, Grey rather than the less distinguished Commons leaders would have been invited to form that government. In this respect Grey's position was like that of the Earl of Derby in the Protectionist Conservative opposition of the late 1840s and early 1850s.[4]

Earl Grey witnessed a delay of about a year, until 1818, before a new leader of the opposition in the House of Commons was chosen. This was George Tierney who was reluctant to accept the leadership and had weak support from his party. On 18 May 1819, Tierney moved a motion in the Commons for a committee on the state of the nation. This motion was defeated by 357 to 178, a division involving the largest number of MPs until the debates over the Reform bill in the early 1830s. Foord comments that "this defeat put an effective end to Tierney's leadership ... Tierney did not disclaim the leadership till 23 Jan. 1821 ..., but he had ceased to exercise its functions since the great defeat".

Between 1821 and 1830 the Whig Commons leadership was left vacant. The leadership in the House of Lords was not much more effective: in 1824 Grey retired from active leadership, asking the party to follow the Marquess of Lansdowne "as the person whom his friends were to look upon as their leader". Lansdowne disclaimed the title of leader, although in practice he performed the function.

Following the retirement of Lord Liverpool from the prime ministership in 1827, the party political situation changed. Neither the Duke of Wellington or Robert Peel agreed to serve under George Canning and they were followed by five other members of the former Cabinet as well as forty junior members of the previous government. The Tory Party was heavily split between the "High Tories" (or "Ultras", nicknamed after the contemporary party in France) and the moderates supporting Canning, often called 'Canningites'. As a result, Canning found it difficult to maintain a government and chose to invite a number of Whigs to join his Cabinet, including Lord Lansdowne. After Canning's death, Lord Goderich continued the coalition for a few more months.The principal opposition between April 1827 and January 1828 worked with these brief administrations, although Earl Grey and a section of the Whigs were also in opposition to the coalition government. It was during this period that the term "His Majesty's Opposition" for the Opposition was coined, by John Cam Hobhouse.[5]

The Duke of Wellington formed a ministry in January 1828 and as a direct effect of adopting in earnest the policy of Catholic Emancipation the opposition became composed of most Whigs with many Canningites and some ultra-Tories. Lord Lansdowne, in the absence of any alternative, remained the leading figure in the Whig opposition.

In 1830 Grey returned to the front rank of politics. On 30 June 1830 he denounced the government in the House of Lords. He rapidly attracted the support of opponents of the ministry. The renewal of organised opposition was also bolstered earlier in the year by the election of a new leader of the opposition in the House of Commons, the heir of Earl Spencer, Viscount Althorp.

In November 1830 Grey was invited to form a government and resumed the formal leadership of the party and as such Wellington and Peel became the leaders of the opposition in the two Houses, from November 1830.

Leaders of the opposition 1830–1937

In the period of 1830–1937 the normal expectation was that there would be two leading parties (often with smaller allied groups), of which one would form the government and the other the opposition.[6] These parties were expected to have recognised leaders in the two Houses, so there was normally no problem in identifying who led the opposition in each House.

The constitutional convention developed in the nineteenth century was that if one of the leaders was the last prime minister of the party, then he would be considered the overall leader of his party. If that was not the case then the leaders of both Houses were of equal status. As the monarch retained some discretion as to which leader should be invited to form a ministry, it was not always obvious in advance which one would be called upon to do so.

However, as the leadership of the opposition only existed by custom, the normal expectations and conventions were modified by political realities from time to time.

From 1830 until 1846 the Tory/Conservative Party and the Whig Party (increasingly often described with its Radical and other allies as the Liberal Party) alternated in power and provided clear leaders of the opposition.

In 1846 the Conservative Party split into (Protectionist) Conservative and Peelite (or Liberal Conservative) factions. The Protectionists being the larger group, the recognised leaders of the opposition were drawn from their ranks. In the House of Lords, Lord Stanley (soon becoming Earl of Derby) was the Protectionist leader. He was the only established front rank political figure in the faction and thus a very strong candidate to form the next Conservative ministry.

The leadership in the House of Commons was more problematic. Lord George Bentinck, the leader of the Protectionist revolt against Sir Robert Peel, initially led the party in the Commons. He resigned in December 1847. The party was then faced with the problem of how to produce a credible leader, who was not Benjamin Disraeli. The first attempt to square the circle, was made in February 1848, when the young Marquess of Granby was installed as the leader. He gave up the post in March 1848. The leadership then fell vacant until February 1849.

The next experiment was to entrust the leadership to a triumvirate of Granby, Disraeli and the elderly John Charles Herries. In practice Disraeli ignored his co-triumvirs. In 1851 Granby resigned and the party accepted Disraeli as the sole leader. The Protectionists by then were clearly the core of the Conservative Party and Derby was able to form his first government in 1852.

The Liberal Party was formally founded in 1859, replacing the Whig Party as one of the two leading parties. With increasing party discipline it became easier to define the principal opposition party and the Leaders of the Opposition.

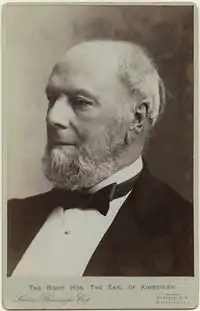

The last overall leader of the opposition to have led it from the House of Lords was the Earl of Rosebery. He resigned as such in November 1896. Lord Rosebery had been Liberal prime minister from 1894 to 1895.

The Parliament Act 1911 removed the legislative veto from the House of Lords to permit the welfare-state forming Liberal legislation to be enacted by the Commons, the People's Budget and any future Money Bills without any input from the Lords. This therefore entrenched the de facto position that there could only be one true oeader of the opposition and in effect clarified in which house that leader would need to sit. From this point, all leaders of the opposition in the House of Commons would thus be overall leaders of the opposition.

In 1915 the Liberal, Conservative and Labour parties formed a coalition. The Irish Parliamentary Party did not join the government but were by and large not in opposition to it. As almost nobody in the Parliament could be said to be in opposition to the coalition, the leaderships of the opposition in both Houses fell vacant.

Sir Edward Carson, the leading figure among the Irish Unionist part of the Conservative and Unionist Party, resigned from the coalition ministry on 19 October 1915. He then became the leader of those Unionists who were not members of the government, effectively leader of the opposition in the Commons.

The party situation changed in December 1916: a leading Liberal, David Lloyd George, formed a coalition with the support of a section of "Coalition Liberal", Conservative and Labour parties. The Liberal leader, H. H. Asquith, and most of his leading colleagues left the government and took up seats on the opposition side of the House of Commons. Asquith was recognised as the leader of the opposition. He retained that post until he was defeated in the 1918 United Kingdom general election. Although Asquith continued to be the leader of the Liberal Party, as he was not a member of the House of Commons he was not eligible to be leader of the opposition.

The Parliament elected in December 1918 which sat from 1919 until 1922, represents the most significant deviation from the principle that the leader of the opposition is the leader of the party not in government with the greatest numerical support in the House of Commons. The largest opposition party (disregarding Sinn Féin, whose MPs did not take their seats at Westminster), was the Labour Party which had wholly left the Lloyd George coalition and won 57 seats at the general election. Thirty six Liberals had been elected without coalition support however were mixed in their opposition to Lloyd George. The Labour Party did not have a leader until 1922. The Parliamentary Labour Party annually elected a chairman, but the party, due to its congressional origins, refused to assert a claim that the chairman was the leader of the opposition. Although the issue of who was entitled to be leader of the opposition was never formally resolved, in practice the Opposition Liberal leader performed most of the parliamentary functions associated with the office.

The small group of opposition Liberals met in 1919, distanced by his coalition's protectionism and nationalization. They resolved that they were the Liberal Parliamentary Party. They elected Sir Donald Maclean as Chairman of the Parliamentary Party. Liberal Party practice at the time, when the overall leader of the party had lost an election to the House of Commons, was for the chairman to function as acting leader in the House. Maclean therefore took on the role of leader of the opposition, followed by Asquith, who returned to the House by winning a by-election (1920–22).

From 1922 the Labour Party had a recognised leader so took over all remaining commons opposition roles from the Opposition Liberal Party. Since 1922 the principal Government and Opposition parties have been the Labour Party and the Conservative Party. There were three instances of peers being seriously considered for the prime ministership, during the twentieth century (Curzon of Kedleston in 1923, Halifax in 1940 and Home in 1963), but these were all cases where the Conservative Party was in government and do not affect the list of leaders of the opposition.

In 1931–32 the leader of the Labour Party was Arthur Henderson. He was leader of the opposition for a short period in 1931, but was ineligible to continue when he lost his seat in the 1931 general election. George Lansbury was leader of the opposition before he also became the leader of the Labour Party in 1932.

Statutory leaders of the opposition from 1937

Leaders of the opposition in the two Houses of Parliament had been generally recognised and given a special status in Parliament for more than a century before they were mentioned in legislation.

Erskine May: Parliamentary Practice confirms that the office of leader of the opposition was first given statutory recognition in the Ministers of the Crown Act 1937.

- Section 5 states that "There shall be paid to the Leader of the Opposition an annual salary of two thousand pounds".

- Section 10(1) includes a definition (which codifies the usual situation under the previous custom) "Leader of the Opposition" means that member of the House of Commons who is for the time being the leader in that House of the party in opposition to His Majesty's Government having the greatest numerical strength in that House".

- The 1937 Act also contains an important provision to decide who is the Leader of the Opposition, if this is in doubt. Under section 10(3) "If any doubt arises as to which is or was at any material time the party in opposition to His Majesty's Government having the greatest numerical strength in the House of Commons, or as to who is or was at any material time the leader in that House of such a party the question shall be decided for the purposes of this Act by the Speaker of the House of Commons, and his decision, certified in writing under his hand, shall be final and conclusive".

Subsequent legislation also gave statutory recognition to the leader of the opposition in the House of Lords.

- Section 2(1) of the Ministerial and other Salaries Act 1975, provides that "In this Act "Leader of the Opposition" means, in relation to either House of Parliament, that member of that House who is for the time being the Leader in that House of the party in opposition to Her Majesty's Government having the greatest numerical strength in the House of Commons".

- Section 2(2) is in exactly the same terms as section 10(3) of the 1937 Act (apart from substituting Her Majesty's for His Majesty's).

- Section 2(3) is a corresponding provision for the Lord Chancellor (since 2005, the Lord Speaker) to decide about the Leader of the Opposition in the House of Lords.

The legislative provisions confirm that leader of the opposition is, strictly, a Parliamentary office; so that to be leader a person must be a member of the House in which he or she leads.

Since 1937 the leader of the opposition has received a state salary in addition to their salary as a Member of Parliament (MP), now equivalent to a Cabinet Minister. The holder also receives a chauffeur-driven car for official business of equivalent cost and specification to the vehicles used by most cabinet ministers.

In 1940 the three largest parties in the House of Commons formed a coalition government to continue to prosecute the Second World War. This coalition continued in office until shortly after the defeat of Germany in 1945. As the former leader of the opposition had joined the government the issue arose of who was to hold the office or perform its functions. Keesing's Contemporary Archives 1937–1940 (at paragraph 4069D) reported the situation, based on Hansard:

The Prime Minister replying to Mr Denman in the House of Commons on 21 May, said that in view of the formation of an Administration embracing the three main political parties, H.M. Government was of the opinion that the provision of the Ministers of the Crown Act, 1937, relating to the payment of a salary to the leader of the opposition was in abeyance for the time being, as there was no alternative party capable of forming a Government. He added that he did not consider amending legislation necessary.

The Daily Herald reported that the Parliamentary Labour Party met on 22 May 1940 and unanimously elected Dr H.B. Lees-Smith as Chairman of the PLP (an office normally held by the party leader at that time) and as spokesman of the Party from the opposition front bench.

After the death of Lees-Smith, on 18 December 1941, the PLP held a meeting on 21 January 1942. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence was unanimously elected Chairman of the PLP and the official spokesman of the party in the House of Commons while the party leader was serving in the government. After the deputy leader of the party (Arthur Greenwood) left the government on 22 February 1942 he took over these roles from Pethick-Lawrence until the end of the coalition and the resumption of normal party politics.

List of leaders of the opposition

The table lists the people who were, or who acted as, leaders of the opposition in the two Houses of Parliament since 1807, prior to which the post was held by Charles James Fox for decades.

The leaders of the two Houses were of equal status, before 1911, unless one was the most recent Prime Minister for the party. Such a former prime minister was considered to be the overall leader of the opposition. From 1911 the Leader of the Opposition in the House of Commons was considered to be the overall Leader of the Opposition. Overall leaders names are bolded. Acting leaders names are in italics unless the acting leader subsequently became a full leader during a continuous period as leader.

Due to the fragmentation of both principal parties in 1827–30, the leaders and principal opposition parties suggested for those years are provisional.

Notes and references

- Notes

- † Died in office

- 1 Formerly Prime Minister

- 2 Subsequently Prime Minister

- 3 Formerly and subsequently Prime Minister

- A Foord suggests that Lansdowne was, in effect, Acting Whig Leader in 1824–27. This may possibly have also been the case in 1828–30. Grey's article in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography suggests "... though he called on Lansdowne to take up the leadership of the opposition he was still unwilling to give it up altogether". Grey was in opposition in 1827–28, when Lansdowne was in government. Given the confusion of the politics of the period, particularly after 1827 when both principal parties were fragmented, it is possible that Grey should be considered Leader of the Opposition 1824–1830. However the definite statements (by Foord) that Grey resigned the leadership in 1824 and (by Cook & Keith) that Grey did not resume the leadership until November 1830 leads to a different conclusion.

- B An alternative interpretation is that Palmerston (the immediate past Prime Minister) and Lord John Russell (a previous Prime Minister) were joint leaders. Cook & Keith have Palmerston as the sole leader.

- C Harcourt resigned 14 December 1898.

- D Rosebery resigned 6 October 1896.

- E Balfour lost his seat in the House of Commons in January 1906.

- F During Asquith's coalition government of 1915–1916, there was no formal opposition in either the Commons or the Lords. The only party not in Asquith's Liberal, Conservative, Labour Coalition was the Irish Nationalist Party led by John Redmond. However, this party supported the government and did not function as an Opposition. Sir Edward Carson, the leading figure amongst the Irish Unionist allies of the Conservative Party, resigned from the coalition ministry on 19 October 1915. He then became the de facto leader of those Unionists who were not members of the government, effectively Leader of the Opposition in the Commons.

- G Asquith lost his seat in the House of Commons in December 1918.

- H Douglas in The History of the Liberal Party 1895–1970 observes that "The technical question whether the Leader of the Opposition was Maclean or William Adamson, Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party, was never fully resolved ... The fact that Adamson did not press his claim for Opposition leadership is of more than technical interest, for it shows that the Labour Party was still not taking itself seriously as a likely alternative government".

- I The Labour Party did not appoint a leader in the Lords until it formed its first government in 1924.

- J Henderson lost his seat in the House of Commons on 27 October 1931.

- K Lansbury was acting as leader, in the absence from the House of Commons of Henderson, in 1931–1932; before becoming party leader himself in 1932.

- L Attlee was acting as leader, after the resignation of Lansbury on 25 October 1935, before being elected party leader himself on 3 December 1935.

- M During World War II a succession of three Labour politicians acted as Leader of the Opposition for the purpose of allowing the House of Commons to function normally, however as in the mid World War I ministry, opposition did not run under a party-whipped system. As the Government 1940–45 was a coalition government in which Labour politicians functioned fully as members of the Government: neither Deputy Prime Minister Clement Attlee nor these three received the salary for the post of Leader of the Opposition. The largest party that opposed the war and was not part of the coalition – and therefore, in theory, the opposition was the Independent Labour Party led by James Maxton. With only three MPs, it tried to take over the opposition frontbench but was widely opposed in this venture.

- N Lord Addison was not a member of the wartime coalition government. When Labour was part of the government from May 1940 until May 1945, Addison functioned as a formal, procedural Opposition Leader, in the same way as the acting Leaders of the Opposition in the House of Commons.

- O Formally held a House of Lords seat as Baron Cecil, of Essendon in the County of Rutland, usually a subsidiary title (and the most junior title) of the Marquess of Salisbury. Viscount Cranborne is a more senior subsidiary title of the Marquess of Salisbury, and usually used as a courtesy title by the sitting Marquess's eldest son. Two Lords Cranborne were introduced to the House of Lords during the lifetime of their fathers via the unusual route of a writ of acceleration. This allowed each to become a substantive peer using the third family title, Baron Cecil, entitling father and son to sit in the House at the same time. In line with House of Lords custom on each occasion the new peer chose to continue to be known by their more senior (courtesy) title. [7][8]

- P Commonly referred to as the acting leader, following the death or immediate resignation of the leader, but is, according to the Labour Party Rule Book, fully leader until the next leader is selected. Before 1981 the leader, in opposition, was elected annually by the parliamentary Labour Party. From 1981 to 2010, the leader was elected by an electoral college of party members, MPs and MEPs, as well as trade unions before the party switched to a true one member, one vote system in 2015.

List of Leaders of the Opposition by length of tenure

This list notes each Leader of the Opposition, from the Parliament Act 1911 granting legislative preeminence to the House of Commons,[9] and the Ministers of the Crown Act 1937 the leader of the second largest faction within it a statutory title and salary,[10] rather than the customary role as HM Official Opposition,[11] in order of term length. This is based on the difference between dates; if counted by number of calendar days all the figures would be one greater.

Of the 34 Leaders of the Opposition, 6 served more than 5 years (1826.25 days), 4 have lost more than one general election, and 7 have served less than a year.

See also

References

- "Appendix 3: Ministerial salaries – salary entitlements" (PDF). House of Commons Library. p. 51. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Pay and expenses for MPs". parliament.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Keir Starmer elected as new Labour leader". BBC. 4 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- His Majesty's Opposition 1714–1830, Archibald S. Foord, Oxford University Press (1964), 494 pages ISBN 0198213115.

- His Majesty's Opposition 1714–1830, Archibald S. Foord, Greenwood Press, 1979, 494 pages, page 1.

- The discussion in this section is based upon British Historical Facts 1830–1900 and Twentieth Century British Political Facts 1900–2000.

- https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/people/viscount-cranborne-1/index.html

- "No. 52911". The London Gazette. 5 May 1992. p. 7756.

- "Parliament act 1911". Gov.uk. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- "Ministers of the Crown Act 1937". Modern Law Review. Blackwell Publishing. 1 (2): 145–148. 1937. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2230.1937.tb00014.x. ISSN 0026-7961. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- "Her Majesty's Official Opposition". Parliament.uk. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- "Past Prime Ministers". Gov.uk. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- "United Kingdom Election Results". United Kingdom Election Results. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- "Keir Starmer elected as new Labour leader". BBC News. 4 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

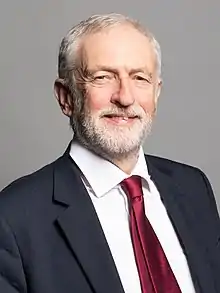

- Watson, Ian. "Jeremy Corbyn: 'I will not lead Labour at next election'". BBC News. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- "Jeremy Corbyn wins Labour leadership contest". BBC News. 12 September 2015. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- "Labour Party leaders and officials since 1975". Parliament.uk. House of Commons library. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- "Ed Miliband is elected leader of the Labour Party". BBC News. 25 September 2010. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010.

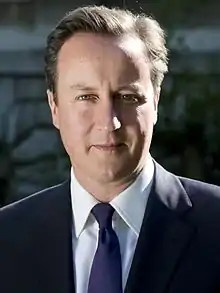

- "Cameron chosen as new Tory leader". BBC News. 6 December 2005. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- "Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975". Parliament.UK. House of Commons Library. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- "Leader of the Opposition". Hansard 1803-2005. Parliament.UK. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Thorpe, D.R. (1996). Alec Douglas-Home. Sinclair-Stevenson. p. 384. ISBN 9781856192774. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Heppell, T. (2012). Leaders of the Opposition: From Churchill to Cameron. Springer. ISBN 9780230369009. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Thorpe, Andrew (2008). A History of the British Labour Party (3rd ed.). Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 107. ISBN 9781137248152. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Ruston, Alan. "Frederick Pethick-Lawrence". Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Sugarman, Daniel. "MP Hastings Bertrand Lees-Smith saved dozens of lives, but had no idea". The JC. The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Clarke, Charles (2015). British Labour Leaders. Biteback Publishing. ISBN 9781849549677. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Baldwin, Stanley (2004). Baldwin Papers: A Conservative Statesman, 1908-1947. CUP. p. 140. ISBN 9780521580809. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Bentley, Michael (2007). The Liberal Mind 1914-29. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780521037426. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Mulhall, Ed. "Carson, Redmond, the Coalition and the War, 1915". RTÉ. Boston College. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Bandow, Doug. "Would WWI or WWII Have Happened Without This Prime Minister?". CATO institute. American Spectator (Online). Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "People - Mr Bonar Law". Hansard 1803-2005. Parliament.UK. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

Bibliography

- British Historical Facts 1760–1830, by Chris Cook and John Stevenson (The Macmillan Press 1980)

- British Historical Facts 1830–1900, by Chris Cook and Brendan Keith (The Macmillan Press 1975)

- His Majesty's Opposition 1714–1830, by Archibald S. Foord (Oxford University Press and Clarendon Press, 1964)

- History of the Liberal Party 1895–1970, by Roy Douglas (Sidgwick & Jackson 1971)

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Twentieth Century British Political Facts 1900–2000, by David Butler and Gareth Butler (Macmillan Press 8th edition, 2000)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_Neal_Kinnoch_%252C_k%252C_Bestanddeelnr_932-9811.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)