Transit of Venus

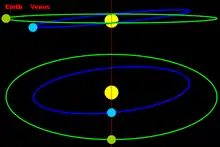

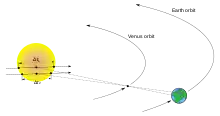

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a transit, Venus can be seen from Earth as a small black dot moving across the face of the Sun. The duration of such transits is usually several hours (the transit of 2012 lasted 6 hours and 40 minutes). A transit is similar to a solar eclipse by the Moon. While the diameter of Venus is more than three times that of the Moon, Venus appears smaller, and travels more slowly across the face of the Sun, because it is much farther away from Earth.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Transits of Venus are among the rarest of predictable astronomical phenomena.[1] They occur in a pattern that generally repeats every 243 years, with pairs of transits eight years apart separated by long gaps of 121.5 years and 105.5 years. The periodicity is a reflection of the fact that the orbital periods of Earth and Venus are close to 8:13 and 243:395 commensurabilities.[2][3]

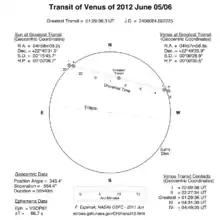

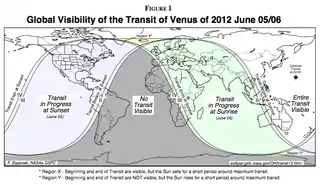

The last transit of Venus was on 5 and 6 June 2012, and was the last Venus transit of the 21st century; the prior transit took place on 8 June 2004. The previous pair of transits were in December 1874 and December 1882. The next transits of Venus will take place on 10–11 December 2117 and 8 December 2125.[4][5][6]

Venus transits are historically of great scientific importance as they were used to gain the first realistic estimates of the size of the Solar System. Observations of the 1639 transit provided an estimate of both the size of Venus and the distance between the Sun and the Earth that was more accurate than any other up to that time. Observational data from subsequent predicted transits in 1761 and 1769 further improved the accuracy of this initial estimated distance through the use of the principle of parallax. The 2012 transit provided scientists with a number of other research opportunities, particularly in the refinement of techniques to be used in the search for exoplanets.

Conjunctions

Venus, with an orbit inclined by 3.4° relative to the Earth's, usually appears to pass under (or over) the Sun at inferior conjunction.[7] A transit occurs when Venus reaches conjunction with the Sun at or near one of its nodes—the longitude where Venus passes through the Earth's orbital plane (the ecliptic)—and appears to pass directly across the Sun. Although the inclination between these two orbital planes is only 3.4°, Venus can be as far as 9.6° from the Sun when viewed from the Earth at inferior conjunction.[8] Since the angular diameter of the Sun is about half a degree, Venus may appear to pass above or below the Sun by more than 18 solar diameters during an ordinary conjunction.[7]

Sequences of transits usually repeat every 243 years. After this period of time Venus and Earth have returned to very nearly the same point in their respective orbits. During the Earth's 243 sidereal orbital periods, which total 88,757.3 days, Venus completes 395 sidereal orbital periods of 224.701 days each, equal to 88,756.9 Earth days. This period of time corresponds to 152 synodic periods of Venus.[9]

The pattern of 105.5, 8, 121.5 and 8 years is not the only pattern that is possible within the 243-year cycle, because of the slight mismatch between the times when the Earth and Venus arrive at the point of conjunction. Prior to 1518, the pattern of transits was 8, 113.5 and 121.5 years, and the eight inter-transit gaps before the AD 546 transit were 121.5 years apart. The current pattern will continue until 2846, when it will be replaced by a pattern of 105.5, 129.5 and 8 years. Thus, the 243-year cycle is relatively stable, but the number of transits and their timing within the cycle will vary over time.[9][10] Since the 243:395 Earth:Venus commensurability is only approximate, there are different sequences of transits occurring 243 years apart, each extending for several thousand years, which are eventually replaced by other sequences. For instance, there is a series which ended in 541 BC, and the series which includes 2117 only started in AD 1631.[9]

History of observation

Ancient and medieval history

Ancient Indian, Greek, Egyptian, Babylonian and Chinese observers knew of Venus and recorded the planet's motions. The early Greek astronomers called Venus by two names—Hesperus the evening star and Phosphorus the morning star.[11] Pythagoras is credited with realizing they were the same planet. There is no evidence that any of these cultures knew of the transits. Venus was important to ancient American civilizations, in particular for the Maya, who called it Noh Ek, "the Great Star" or Xux Ek, "the Wasp Star";[12] they embodied Venus in the form of the god Kukulkán (also known as or related to Gukumatz and Quetzalcoatl in other parts of Mexico). In the Dresden Codex, the Maya charted Venus's full cycle, but despite their precise knowledge of its course, there is no mention of a transit.[13] However, it has been proposed that frescoes found at Mayapan may contain a pictorial representation of the 12th or 13th century transits.[14]

The Persian polymath Avicenna claimed to have observed Venus as a spot on the Sun. This is possible, as there was a transit on May 24, 1032, but Avicenna did not give the date of his observation, and modern scholars have questioned whether he could have observed the transit from his location at that time; he may have mistaken a sunspot for Venus. He used his transit observation to help establish that Venus was, at least sometimes, below the Sun in Ptolemaic cosmology,[15] i.e. the sphere of Venus comes before the sphere of the Sun when moving out from the Earth in the prevailing geocentric model.[16][17]

1639 – first scientific observation

In 1627, Johannes Kepler became the first person to predict a transit of Venus, by predicting the 1631 event. His methods were not sufficiently accurate to predict that the transit would not be visible in most of Europe, and as a consequence, nobody was able to use his prediction to observe the phenomenon.[18]

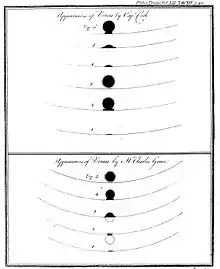

The first recorded observation of a transit of Venus was made by Jeremiah Horrocks from his home at Carr House in Much Hoole, near Preston in England, on 4 December 1639 (24 November under the Julian calendar then in use in England). His friend, William Crabtree, also observed this transit from Broughton, near Manchester.[19] Kepler had predicted transits in 1631 and 1761 and a near miss in 1639. Horrocks corrected Kepler's calculation for the orbit of Venus, realized that transits of Venus would occur in pairs 8 years apart, and so predicted the transit of 1639.[20] Although he was uncertain of the exact time, he calculated that the transit was to begin at approximately 15:00. Horrocks focused the image of the Sun through a simple telescope onto a piece of paper, where the image could be safely observed. After observing for most of the day, he was lucky to see the transit as clouds obscuring the Sun cleared at about 15:15, just half an hour before sunset. Horrocks's observations allowed him to make a well-informed guess as to the size of Venus, as well as to make an estimate of the mean distance between the Earth and the Sun – the astronomical unit (AU). He estimated that distance to be 59.4 million mi (95.6 million km; 0.639 AU) – about two thirds of the actual distance of 93 million mi (150 million km), but a more accurate figure than any suggested up to that time. The observations were not published until 1661, well after Horrocks's death.[20] Horrocks based his calculation on the (false) presumption that each planet's size was proportional to its rank from the Sun, not on the parallax effect as used by the 1761 and 1769 and following experiments.

1761 and 1769

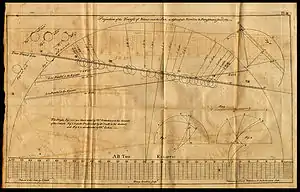

In 1663 Scottish mathematician James Gregory had suggested in his Optica Promota that observations of a transit of the planet Mercury, at widely spaced points on the surface of the Earth, could be used to calculate the solar parallax and hence the astronomical unit using triangulation. Aware of this, a young Edmond Halley made observations of such a transit on 28 October O.S. 1677 from Saint Helena but was disappointed to find that only Richard Towneley in Burnley, Lancashire had made another accurate observation of the event whilst Gallet, at Avignon, simply recorded that it had occurred. Halley was not satisfied that the resulting calculation of the solar parallax at 45" was accurate.

In a paper published in 1691, and a more refined one in 1716, he proposed that more accurate calculations could be made using measurements of a transit of Venus, although the next such event was not due until 1761 (6 June N.S., 26 May O.S.).[21][22] Halley died in 1742, but in 1761 numerous expeditions were made to various parts of the world so that precise observations of the transit could be made in order to make the calculations as described by Halley—an early example of international scientific collaboration.[23] This collaboration was, however, underpinned by competition, the British, for example, being spurred to action only after they heard of French plans from Joseph-Nicolas Delisle. In an attempt to observe the first transit of the pair, astronomers from Britain (William Wales and Captain James Cook), Austria (Maximilian Hell) and France (Jean-Baptiste Chappe d'Auteroche and Guillaume Le Gentil) traveled to destinations around the world, including Siberia, Newfoundland and Madagascar.[24] Most managed to observe at least part of the transit, particularly successful observations were made by Jeremiah Dixon and Charles Mason at the Cape of Good Hope.[25] Less successful, at Saint Helena, were Nevil Maskelyne and Robert Waddington, although they put the voyage to good use by trialling the lunar-distance method of finding longitude.[26]

That Venus might have an atmosphere was widely expected (because of the plurality of worlds belief) even before the transit of 1761. However, few if any seem to have predicted that it might be possible to actually detect it during the transit. The actual discovery of the atmosphere on Venus has long been attributed to the Russian Academician Mikhail Lomonosov on the basis of his observation of the transit of Venus of 1761 from the Imperial Academy of Sciences of St. Petersburg.[27] At least in the English-speaking world, this attribution seems to have been owing to comments from the multi-lingual popular astronomy writer Willy Ley (1966), who consulted sources in both Russian and German, and wrote that Lomonosov observed a luminous ring (this was Ley's interpretation and was not indicated in quotes) and inferred from it the existence of an atmosphere “maybe greater than that of the Earth” (which was in quotes). Because many modern transit observers have also seen a threadlike arc produced by refraction of sunlight in the atmosphere of Venus when the planet has progressed off the limb of the Sun, it has generally, if rather uncritically, been assumed that this was the same thing that Lomonosov saw. Indeed, the term “Lomonosov’s arc” has frequently been used in the literature.[28] In 2012, Pasachoff and Sheehan[29] consulted original sources, and questioned the basis for the claim that Lomonosov observed the thin arc produced by the atmosphere of Venus. A reference to the paper was even picked up by the Russian state-controlled media group RIA Novosti on January 31, 2013, under the headline “Astronomical Battle in US Over Lomonosov’s discovery." An interesting attempt was made by a group of researchers to experimentally reconstruct Lomonosov's observation using antique telescopes during the transit of Venus on 5-6 June 2012. One of them, Y. Petrunin, suggested that the telescope Lomonosov actually used was probably a 50 mm Dolland with a magnifying power of 40x. It was preserved at Pulkova Observatory but destroyed when the Germans bombed the observatory during World War II. Thus, Lomonosov's actual telescope was not available, but other presumably similar instruments were employed on this occasion, and led the researchers to affirm their belief that Lomonosov's telescope would have been adequate to the task of detecting the arc.[30] Thus A. Koukarine, using a 67 mm Dollond on Mt. Hamilton, where seeing was likely much better than Lomonosov enjoyed at St. Petersburg, clearly observed the spiderweb-thin arc known to be due to refraction in the atmosphere of Venus. However, Koukarine's sketches do not really resemble the diagram published by Lomonosov. [31][32] On the other hand, Koukarine's colleague V. Shiltsev, who more nearly observed under the same conditions as Lomonosov (using a 40 mm Dollond at Batavia, Illinois), did produce a close duplicate of Lomonosov's diagram; however, the rather large wing of light shown next to the black disk of Venus in his drawing (and Lomonosov's) is too coarse to have been the arc. Instead it appears to be a complicated manifestation of the celebrated optical effect known as the “Black Drop.” (It should be kept in mind that, as stated in Sheehan and Westfall, “optical distortions at the interface between Venus and the Sun during transits are impressively large, and any inferences from them are fraught with peril.”

Again, the actual words used by Lomonosov do not refer to an “arc” at all. In the Russian version, he described a brief brightening lasting a second or so, just before third contact, which appeared to Pasachoff and Sheehan to most probably indicate a last fleeting glimpse of the photosphere. As a check against this, Lomonosov's German version (he had learned to speak and write German fluently as a student at Marburg) was also consulted; he describes seeing “ein ganz helles Licht, wie ein Haar breit”=”a very bright light, as wide as a hair.” Here, the adverb “ganz” in connection with “helles” (bright) could mean “as bright as possible” or “completely bright”), i.e., as bright as the surface brightness of the solar disk, which is even stronger evidence that this can't be Venus's atmosphere, which always appears much fainter. Lomonosov's original sketches, if they existed, do not appear to have survived, Modern observations made during the nineteenth century transits and especially those of 2004 and 2012 suggest that what Lomonosov saw was not the arc associated with the atmosphere of Venus at all but the bright flash of the solar photosphere before third contact. The first observers to record the actual arc associated with the atmosphere of Venus, in a form comporting with modern observations, appear to have been Chappe, Rittenhouse, Wayles and Dymond and several others at the transit in June 1769.

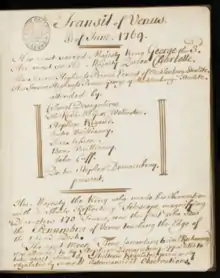

For the 1769 transit (taking place on 3-4 June N.S., 23 May O.S.), scientists traveled to Tahiti,[33] Norway, and locations in North America including Canada, New England, and San José del Cabo (Baja California, then under Spanish control). The Czech astronomer Christian Mayer was invited by Catherine the Great to observe the transit in Saint Petersburg with Anders Johan Lexell, while other members of the Russian Academy of Sciences went to eight other locations in the Russian Empire, under the general coordination of Stepan Rumovsky.[34] George III of the United Kingdom had the King's Observatory built near his summer residence at Richmond Lodge for him and his royal astronomer Stephen Demainbray to observe the transit.[35][36] The Hungarian astronomer Maximilian Hell and his assistant János Sajnovics traveled to Vardø, Norway, delegated by Christian VII of Denmark. William Wales and Joseph Dymond made their observation in Hudson Bay, Canada, for the Royal Society. Observations were made by a number of groups in the British colonies in America. In Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society erected three temporary observatories and appointed a committee, of which David Rittenhouse was the head. Observations were made by a group led by Dr. Benjamin West in Providence, Rhode Island,[37] and published in 1769.[38] The results of the various observations in the American colonies were printed in the first volume of the American Philosophical Society's Transactions, published in 1771.[39] Comparing the North American observations, William Smith published in 1771 a best value of the solar parallax of 8.48 to 8.49 arc-seconds,[40] which corresponds to an Earth-Sun distance of 24,000 times the Earth's radius, about 3% different from the correct value.

Observations were also made from Tahiti by James Cook and Charles Green at a location still known as "Point Venus".[41] This occurred on the first voyage of James Cook,[42] after which Cook explored New Zealand and Australia. This was one of five expeditions organised by the Royal Society and the Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne.

Jean-Baptiste Chappe d'Auteroche went to San José del Cabo in what was then New Spain to observe the transit with two Spanish astronomers (Vicente de Doz and Salvador de Medina). For his trouble he died in an epidemic of yellow fever there shortly after completing his observations.[43] Only 9 of 28 in the entire party returned home alive.[44]

The unfortunate Guillaume Le Gentil spent over eight years travelling in an attempt to observe either of the transits. His unsuccessful journey led to him losing his wife and possessions and being declared dead (his efforts became the basis of the play Transit of Venus by Maureen Hunter) and a subsequent opera, though eventually he regained his seat in the French Academy and had a long marriage.[24] Under the influence of the Royal Society Ruđer Bošković travelled to Istanbul, but arrived too late.[45]

Unfortunately, it was impossible to time the exact moment of the start and end of the transit because of the phenomenon known as the "black drop effect". This effect was long thought to be due to Venus's thick atmosphere, and initially it was held to be the first real evidence that Venus had an atmosphere. However, recent studies demonstrate that it is an optical effect caused by the smearing of the image of Venus by turbulence in the Earth's atmosphere or imperfections in the viewing apparatus along with the extreme brightness variation at the edge (limb) of the Sun as the line-of-sight from Earth goes from opaque to transparent in a small angle.[46][47]

In 1771, using the combined 1761 and 1769 transit data, the French astronomer Jérôme Lalande calculated the astronomical unit to have a value of 153 million kilometers (±1 million km). The precision was less than had been hoped for because of the black drop effect, but still a considerable improvement on Horrocks's calculations.[24]

Maximilian Hell published the results of his expedition in 1770, in Copenhagen.[48] Based on the results of his own expedition, and of Wales and Cook, in 1772 he presented another calculation of the astronomical unit: 151.7 million kilometers.[49][50] Lalande queried the accuracy and authenticity of the Hell expedition, but later he retreated in an article of Journal des sçavans, in 1778.

1874 and 1882

Transit observations in 1874 and 1882 allowed this value to be refined further. Three expeditions—from Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States—were sent to the Kerguelen Archipelago for the 1874 observations.[51] The American astronomer Simon Newcomb combined the data from the last four transits, and he arrived at a value of about 149.59 million kilometers (±0.31 million kilometers). Modern techniques, such as the use of radio telemetry from space probes, and of radar measurements of the distances to planets and asteroids in the Solar System, have allowed a reasonably accurate value for the astronomical unit (AU) to be calculated to a precision of about ±30 meters. As a result, the need for parallax calculations has been superseded.[24][47]

2004 and 2012

A number of scientific organizations headed by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) organized a network of amateur astronomers and students to measure Earth's distance from the Sun during the transit.[52] The participants' observations allowed a calculation of the astronomical unit (AU) of 149,608,708 km ± 11,835 km which had only a 0.007% difference to the accepted value.[53]

There was a good deal of interest in the 2004 transit as scientists attempted to measure the pattern of light dimming as Venus blocked out some of the Sun's light, in order to refine techniques that they hope to use in searching for extrasolar planets.[47][54] Current methods of looking for planets orbiting other stars only work for a few cases: planets that are very large (Jupiter-like, not Earth-like), whose gravity is strong enough to wobble the star sufficiently for us to detect changes in proper motion or Doppler shift changes in radial velocity; Jupiter or Neptune sized planets very close to their parent star whose transit causes changes in the luminosity of the star; or planets which pass in front of background stars with the planet-parent star separation comparable to the Einstein ring and cause gravitational microlensing.[55] Measuring light intensity during the course of a transit, as the planet blocks out some of the light, is potentially much more sensitive, and might be used to find smaller planets.[47] However, extremely precise measurement is needed: for example, the transit of Venus causes the amount of light received from the Sun to drop by a fraction of 0.001 (that is, to 99.9% of its nominal value), and the dimming produced by small extrasolar planets will be similarly tiny.[56]

The 2012 transit provided scientists numerous research opportunities as well, in particular in regard to the study of exoplanets. Research of the 2012 Venus transit includes:[57][58][59]

- Measuring dips in a star's brightness caused by a known planet transiting the Sun will help astronomers find exoplanets. Unlike the 2004 Venus transit, the 2012 transit occurred during an active phase of the 11-year activity cycle of the Sun, and it is likely to give astronomers practice in picking up a planet's signal around a "spotty" variable star.

- Measurements made of the apparent diameter of Venus during the transit, and comparison with its known diameter, will give scientists an idea of how to estimate exoplanet sizes.

- Observation made of the atmosphere of Venus simultaneously from Earth-based telescopes and from the Venus Express gives scientists a better opportunity to understand the intermediate level of Venus's atmosphere than is possible from either viewpoint alone. This will provide new information about the climate of the planet.

- Spectrographic data taken of the well-known atmosphere of Venus will be compared to studies of exoplanets whose atmospheres are thus far unknown.

- The Hubble Space Telescope, which cannot be pointed directly at the Sun, used the Moon as a mirror to study the light that had passed through the atmosphere of Venus in order to determine its composition. This will help to show whether a similar technique could be used to study exoplanets.

Past and future transits

NASA maintains a catalog of Venus transits covering the period 2000 BC to 4000 AD.[60] Currently, transits occur only in June or December (see table) and the occurrence of these events slowly drifts, becoming later in the year by about two days every 243-year cycle.[61] Transits usually occur in pairs, on nearly the same date eight years apart. This is because the length of eight Earth years is almost the same as 13 years on Venus, so every eight years the planets are in roughly the same relative positions. This approximate conjunction usually results in a pair of transits, but it is not precise enough to produce a triplet, since Venus arrives 22 hours earlier each time. The last transit not to be part of a pair was in 1396. The next will be in 3089; in 2854 (the second of the 2846/2854 pair), although Venus will just miss the Sun as seen from the Earth's equator, a partial transit will be visible from some parts of the southern hemisphere.[62]

Thus after 243 years the transits of Venus return. The 1874 transit is a member of the 243-year cycle #1. The 1882 transit is a member of #2. The 2004 transit is a member of #3 and the 2012 transit is a member of #4. The 2117 transit is a member of #1 and so on. However, the ascending node (December transits) of the orbit of Venus moves backwards after each 243 years so the transit of 2854 is the last member of series #3 instead of series #1. The descending node (June transits) moves forwards, so the transit of 3705 is the last member of #2. From −125,000 till +125,000 there are only about ten 243-year series at both nodes regarding all the transits of Venus in this very long time-span, because both nodes of the orbit of Venus move back and forward in time as seen from the Earth.

| Past transits of Venus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date(s) of transit |

Time (UTC) | Notes | Transit path (HM Nautical Almanac Office) | ||

| Start | Mid | End | |||

| 23 November 1396 | 15:45 | 19:27 | 23:09 | Last transit not part of a pair | |

| 25–26 May 1518 | 22:46 25 May | 01:56 26 May | 05:07 26 May |

||

| 23 May 1526 | 16:12 | 19:35 | 21:48 | Last transit before invention of telescope | |

| 7 December 1631 | 03:51 | 05:19 | 06:47 | Predicted by Kepler | |

| 4 December 1639 | 14:57 | 18:25 | 21:54 | First transit to be observed, by Horrocks and Crabtree | |

| 6 June 1761 | 02:02 | 05:19 | 08:37 | Lomonosov, Chappe d'Auteroche and others observe from Russia; Mason and Dixon observe from the Cape of Good Hope. John Winthrop observes from St. John's, Newfoundland[63] | |

| 3–4 June 1769 | 19:15 3 June | 22:25 3 June | 01:35 4 June |

Cook sent to Tahiti to observe the transit, Chappe to San José del Cabo, Baja California and Maximilian Hell to Vardø, Norway. | |

| 9 December 1874 | 01:49 | 04:07 | 06:26 | Pietro Tacchini leads expedition to Muddapur, India. A French expedition goes to New Zealand's Campbell Island and a British expedition travels to Hawaii. | |

| 6 December 1882 | 13:57 | 17:06 | 20:15 | John Philip Sousa composes a march, the "Transit of Venus", in honor of the transit. | |

| 8 June 2004 | 05:13 | 08:20 | 11:26 | Various media networks globally broadcast live video of the Venus transit. | |

5–6 June 2012  |

22:09 5 June | 01:29 6 June | 04:49 6 June |

Visible in its entirety from the Pacific and Eastern Asia, with the beginning of the transit visible from North America and the end visible from Europe. First transit while a spacecraft orbits Venus. |

|

| Future transits of Venus | |||||

| Date(s) of transit |

Time (UTC) | Notes | Transit path (HM Nautical Almanac Office) | ||

| Start | Mid | End | |||

| 10–11 December 2117 | 23:58 10 December | 02:48 11 December | 05:38 11 December |

Visible in entirety in eastern China, Korea, Japan, south of Russian Far East, Taiwan, Indonesia, and Australia. Partly visible in Central Asia, the Middle East, south part of Russia, in India, most of Africa, and on extreme U.S. West Coast. | |

| 8 December 2125 | 13:15 | 16:01 | 18:48 | Visible in entirety in South America and the eastern U.S. Partly visible in Western U.S., Europe, Africa and Oceania. | |

| 11 June 2247 | 08:42 | 11:33 | 14:25 | Visible in entirety in Africa, Europe, and the Middle East. Partly visible in East Asia and Indonesia, and in North and South America. | |

| 9 June 2255 | 01:08 | 04:38 | 08:08 | Visible in entirety in Russia, India, China, and western Australia. Partly visible in Africa, Europe, and the western U.S. | |

| 12–13 December 2360 | 22:32 12 December | 01:44 13 December | 04:56 13 December |

Visible in entirety in Australia and most of Indonesia. Partly visible in Asia, Africa, and the western half of the Americas. | |

| 10 December 2368 | 12:29 | 14:45 | 17:01 | Visible in entirety in South America, western Africa, and the U.S. East Coast. Partly visible in Europe, the western U.S., and the Middle East. | |

| 12 June 2490 | 11:39 | 14:17 | 16:55 | Visible in entirety through most of the Americas, western Africa, and Europe. Partly visible in eastern Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. | |

| 10 June 2498 | 03:48 | 07:25 | 11:02 | Visible in entirety through most of Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and eastern Africa. Partly visible in eastern Americas, Indonesia, and Australia. | |

Over longer periods of time, new series of transits will start and old series will end. Unlike the saros series for lunar eclipses, it is possible for a transit series to restart after a hiatus. The transit series also vary much more in length than the saros series.

Grazing and simultaneous transits

Sometimes Venus only grazes the Sun during a transit. In this case it is possible that in some areas of the Earth a full transit can be seen while in other regions there is only a partial transit (no second or third contact). The last transit of this type was on 6 December 1631, and the next such transit will occur on 13 December 2611.[9] It is also possible that a transit of Venus can be seen in some parts of the world as a partial transit, while in others Venus misses the Sun. Such a transit last occurred on 19 November 541 BC, and the next transit of this type will occur on 14 December 2854.[9] These effects occur due to parallax, since the size of the Earth affords different points of view with slightly different lines of sight to Venus and the Sun. It can be demonstrated by closing an eye and holding a finger in front of a smaller more distant object; when the viewer opens the other eye and closes the first, the finger will no longer be in front of the object.

The simultaneous occurrence of a transit of Mercury and a transit of Venus does occur, but extremely infrequently. Such an event last occurred on 22 September 373,173 BC and will next occur on 26 July 69,163, and—given unlikely assumptions on the constancy of Earth's rotation—again on 29 March 224,508.[64][65] The simultaneous occurrence of a solar eclipse and a transit of Venus is currently possible, but very rare. The next solar eclipse occurring during a transit of Venus will be on 5 April 15,232.[64] The last time a solar eclipse occurred during a transit of Venus was on 1 November 15,607 BC.[66] A few hours after the transit of 3–4 June 1769 there was a total solar eclipse,[67] which was visible in Northern America, Europe, and Northern Asia.

References

- McClure, Bruce (29 May 2012). "Everything you need to know: Venus transit on June 5–6". EarthSky. Earthsky communications Inc. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- Langford, Peter M. (September 1998). "Transits of Venus". La Société Guernesiaise Astronomy Section web site. Astronomical Society of the Channel Island of Guernsey. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- Shortt, David (22 May 2012). "Some Details About Transits of Venus". Planetary Society web site. The Planetary Society. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- Westfall, John E. (November 2003). "June 8, 2004: The Transit of Venus". Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 25 September 2006.

- Westfall, John E. "June 8, 2004: The Transit of Venus". alpo-astronomy.org. Retrieved 8 December 2009.

- Klotz, Irene (6 June 2012). "Venus transit offers opportunity to study planet's atmosphere (+video)". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- "Venus compared to Earth". European Space Agency. 2000. Retrieved 25 September 2006.

- Giesen, Juergen (2003). "Transit Motion Applet". Retrieved 26 September 2006.

- Espenak, Fred (11 February 2004). "Transits of Venus, Six Millennium Catalog: 2000 BCE to 4000 CE". NASA. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011.

- Walker, John. "Transits of Venus from Earth". Fourmilab Switzerland. Retrieved 21 September 2006.

- Rincon, Paul (7 November 2005). "Planet Venus: Earth's 'evil twin'". BBC. Retrieved 25 September 2006.

- Morley, Sylvanus G. (1994). The Ancient Maya (5th ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2310-7.

- Böhm, Bohumil; Böhm, Vladimir. "The Dresden Codex – the Book of Mayan Astronomy". Retrieved 25 September 2006.

- Allen, Jesus Galindo; Allen, Christine (2005). Maya Observations of the 13th Century transits of Venus?. Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 196. IAU. pp. 124–137. Bibcode:2005tvnv.conf..124G. doi:10.1017/S1743921305001328. ISBN 978-0-521-84907-4. ISSN 1743-9213. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- Sally P. Ragep (2007). "Ibn Sīnā: Abū ʿAlī al‐Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbdallāh ibn Sīnā". In Thomas Hockey (ed.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 570–572.

- Goldstein, Bernard R. (1969). "Some Medieval Reports of Venus and Mercury Transits". Centaurus. 14 (1): 49–59. Bibcode:1969Cent...14...49G. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1969.tb00135.x.

- Goldstein, Bernard R. (March 1972). "Theory and Observation in Medieval Astronomy". Isis. 63 (1): 39–47 [44]. Bibcode:1972Isis...63...39G. doi:10.1086/350839.

- van Gent, Robert H. "Transit of Venus Bibliography". Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- Kollerstrom, Nicholas (2004). "William Crabtree's Venus transit observation" (PDF). Proceedings IAU Colloquium No. 196, 2004. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- Marston, Paul (2004). Jeremiah Horrocks—young genius and first Venus transit observer. University of Central Lancashire. pp. 14–37.

- Teets, D.A. (2003). "Transits of Venus and the Astronomical Unit". Mathematics Magazine. 76 (5): 335–348. doi:10.1080/0025570X.2003.11953207. JSTOR 3654879. S2CID 54867823.

- Halley, Edmund (1716). "A New Method of Determining the Parallax of the Sun, or His Distance from the Earth". Philosophical Transactions. XXIX: 454. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011.

- Leverington, David (2003). Babylon to Voyager and beyond: a history of planetary astronomy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 140–142. ISBN 978-0-521-80840-8.

- Pogge, Prof. Richard. "Lecture 26: How far to the Sun? The Venus Transits of 1761 & 1769". Retrieved 25 September 2006.

- Howse, Derek (2004). "Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Jeremiah Dixon". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37360. Retrieved 22 February 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Howse, Derek (1989). Nevil Maskelyne: The Seaman's Astronomer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Vladimir Shiltsev (1970). "Lomonosov's Discovery of Venus Atmosphere in 1761: English Translation of Original Publication with Commentaries". arXiv:1206.3489 [physics.hist-ph].

- Marov, Mikhail Ya. (2004). "Mikhail Lomonosov and the discovery of the atmosphere of Venus during the 1761 transit". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 2004: 209–219. Bibcode:2005tvnv.conf..209M. doi:10.1017/S1743921305001390.

- Sheehan, Jay; Sheehan, William (2012). "Lomonosov, the Discovery of Venus's Atmosphere, and Eighteenth-century Transits of Venus". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 15 (1): 3. Bibcode:2012JAHH...15....3P.

- Alexandre Koukarine; Igor Nesterenko; Yuri Petrunin; Vladimir Shiltsev (27 August 2012). "Experimental Reconstruction of Lomonosov's Discovery of Venus's Atmosphere with Antique Refractors During the 2012 Transit of Venus". Solar System Research. 47 (6): 487–490. arXiv:1208.5286. Bibcode:2013SoSyR..47..487K. doi:10.1134/S0038094613060038. S2CID 119201160.

- Shiltsev, V.; Nesterenko, I.; Rosenfeld, R. (2013). "Replicating the discovery of Venus's atmosphere". Physics Today. 66 (2): 64. Bibcode:2013PhT....66b..64S. doi:10.1063/pt.3.1894. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013.

- Koukarine, A.; et al. (2013). "Experimental Reconstruction of Lomonosov's Discovery of Venus's Atmosphere with Antique Refractors During the 2012 Transit of Venus". Solar System Research. 47 (6): 487–490. arXiv:1208.5286. Bibcode:2013SoSyR..47..487K. doi:10.1134/S0038094613060038. S2CID 119201160.

- "James Cook and the Transit of Venus". NASA Headline News: Science News. nasa.gov. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- Mayer, Christian; Parsons, James (1764). "An Account of the Transit of Venus: In a Letter to Charles Morton, M. D. Secret. R. S. from Christian Mayer, S. J. Translated from the Latin by James Parsons, M. D". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 54: 163–164. Bibcode:1764RSPT...54..163M. doi:10.1098/rstl.1764.0030.

- McLaughlin, Stewart (1992). "The Early History of Kew Observatory". Richmond History: Journal of the Richmond Local History Society. 13: 48–49. ISSN 0263-0958.

- Mayes, Julian (2004). "The History of Kew Observatory". Richmond History: Journal of the Richmond Local History Society. 25: 44–57. ISSN 0263-0958.

- Catherine B. Hurst, Choosing Providence, March 23, 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- West, Benjamin, Account of the Observation of Venus Upon the Sun, The Third Day of June, 1769, at Providence, in New-England, With some Account of the Use of Those Observations, John Carter, 1769 (retrieved 20 April 2016); with extended abstract published in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 1, pp. 97–105

- American Philosophical Society, Transactions (Old Series, vol. 1, 1769–71): see Google Books link (retrieved 20 April 2016).

- W. Smith, "The Sun's Parallax deduced from a comparison of the Norriton and some other American Observations of the Transit of Venus 1769, with the Greenwich and other European Observations of the Same," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Vol 1 (1871), p. 54–72. Solar parallax is defined as "the angle which the Earth's semi-diameter [i.e., radius] subtends at the sun".

- See, for example, Stanley, David (2004). Moon Handbooks South Pacific (8th ed.). Avalon Travel Publishing. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-56691-411-6.

point venus cook.

- Rhys, Ernest, ed. (1999). The Voyages of Captain Cook. Wordsworth Editions Ltd. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-84022-100-8.

- In Memoriam Archived 5 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine French_Academy_of_Sciences

- Anderson, Mark (2012). The Day the World Discovered the Sun: An Extraordinary Story of Scientific Adventure and the Race to Track the Transit of Venus. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82038-0.

- Ruđer Bošković, Giornale di un viaggio da Constantinopoli in Polonia, 1762

- "Explanation of the Black-Drop Effect at Transits of Mercury and the Forthcoming Transit of Venus". AAS. 4 January 2004. Archived from the original on 10 July 2006. Retrieved 21 September 2006.

- "Transits of Venus – Kiss of the goddess". The Economist. 27 May 2004. Retrieved 25 September 2006.

- R. P. Maximiliani Hell e S. J. – Observatio transitus Veneris ante discum Solis die 3. junii anno 1769. Wardoëhusii, auspiciis potentissimi ac clementissimi regis Daniae et Norvegiae, Christiani septimi, facta et societati reg. scientiarum Hafniensi die 24. Novembris 1769. Praelecta. Hafniae, typ. Orphanotrophii regii, excudit Gerhard Wiese Salicath, 82 p.

- Ephemerides astronomicae, anni 1773. Adjecta Collectione omnium observationum transitus Veneris ante discum Solis diei 3. Junii 1769. per orbem universum factorum, atque Appendice de parallaxi Solis ex observationibus tarnsitus Veneris anni 1769. Vindobonae, 1773, typ. Trattner, 311, 121 p.

- De parallaxi Solis ex observationibus transitus Veneris anni 1769. Vindobonae, 1772, typ. J. Trattner, 116 p.

- "1874 transit". Royal Society. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- European Southern Observatory. "The Venus Transit 2004". Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- European Southern Observatory. "Summing Up the Unique Venus Transit 2004 (VT-2004) Programme". Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- McKee, Maggie (6 June 2004). "Extrasolar planet hunters eye Venus transit". New Scientist. Retrieved 27 September 2006.

- Gould, A.; et al. (10 June 2006). "Microlens OGLE-2005-BLG-169 Implies That Cool Neptune-like Planets Are Common". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 644 (1): L37–L40. arXiv:astro-ph/0603276. Bibcode:2006ApJ...644L..37G. doi:10.1086/505421. S2CID 14270439.

- Espenak, Fred (18 June 2002). "2004 and 2012 Transits of Venus". NASA. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- Wall, Michael (16 May 2012). "Venus Transit On June 5 May Bring New Alien Planet Discoveries". space.com. TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- "Counting down to the Transit of Venus – our nearest exoplanet test-lab", phys.org, 5 March 2012

- "The Venus Twilight Experiment: Refraction and scattering phenomena during the transit of Venus on June 5–6, 2012", venustex.oca.eu.

- "NASA - Catalog of Transits of Venus". NASA. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- Although transits occurred in May and November before 1631, this apparent jump in dates was due to the changeover from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar on 15 October 1582

- Bell, Steve (2004). "Transits of Venus 1000 AD – 2700 AD". HM Nautical Almanac Office. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 25 September 2006.

- Winthrop, John (1764). "Observation of the Transit of Venus, June 6, 1761, at St. John's, Newfoundland". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 54: 279–283. doi:10.1098/rstl.1764.0048.

- "Hobby Q&A", Sky&Telescope, August 2004, p. 138

- Espenak, Fred (21 April 2005). "Transits of Mercury, Seven Century Catalog: 1601 CE to 2300 CE". NASA. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 27 September 2006.

- Jeliazkov, Jeliazko. "Simultaneous occurrence of solar eclipse and a transit". transit.savage-garden.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- Lalande, Jérôme; Messier, Charles (1769). "Observations of the Transit of Venus on 3 June 1769, and the Eclipse of the Sun on the Following Day, Made at Paris, and Other Places. Extracted from Letters Addressed from M. de La Lande, of the Royal Academy of Sciences at Paris, and F. R. S. to the Astronomer Royal; And from a Letter Addressed from M. Messier to Mr. Magalhaens". Philosophical Transactions. 59: 374–377. Bibcode:1769RSPT...59..374D. doi:10.1098/rstl.1769.0050.

Further reading

- Hufbauer, Karl (1991). Exploring the Sun, Solar Science Since Galileo. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-0-8018-4098-2.

- Anderson, Mark (2012). The Day the World Discovered the Sun: An Extraordinary Story of Scientific Adventure and the Race to Track the Transit of Venus. Boston: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82038-0.

- Chauvin, Michael (2004). Hokuloa: The British 1874 Transit of Venus Expedition to Hawaii. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 978-1-58178-023-9.

- Lomb, Nick (2011). Transit of Venus: 1631 to the Present. Sydney, Australia: NewSouth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-74223-269-0. OCLC 717231977.

- Maor, Eli (2000). Venus in Transit. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11589-4.

- Maunder, Michael; Moore, Patrick (2000). Transit: When Planets Cross the Sun. London: Springer-Verlaf. ISBN 978-1-85233-621-9.

- Sellers, David (2001). The Transit of Venus: The Quest to Find the True Distance of the Sun. Leeds, UK: Magavelda Press. ISBN 978-0-9541013-0-5.

- Sheehan, William; Westfall, John (2004). The Transits of Venus. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-59102-175-9.

- Simaan, Arkan (May 2004). "The transit of Venus across the Sun" (PDF). Physics Education. 39 (3): 247–251. Bibcode:2004PhyEd..39..247S. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/39/3/001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2007.

- Woodruff, John (2012). Transiting the Sun: Venus and the Key to the Size of the Cosmos. Oxford: Huxley Scientific Press. ISBN 978-0-9522671-6-4.

- Wulf, Andrea (2012). Chasing Venus: The Race to Measure the Heavens. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-70017-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Transits of Venus. |

| Wikisource has several original texts related to: Transit of Venus |

General

- Venus Transits: Measuring the Solar System

- Historical observations of the transit of Venus

- Edmond Halley's 1716 paper describing how transits could be used to measure the Sun's distance, translated from Latin.

- Chasing Venus: Observing the Transits of Venus, 1631–2004 (Smithsonian Libraries)

- Merrifield, Michael. "Venus Transit". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.