Richmond, London

Richmond is a town in south-west London,[nb 1][2][3][4][5] 8.2 miles (13.2 km) west-southwest of Charing Cross. It is on a meander of the River Thames, with many parks and open spaces, including Richmond Park, and many protected conservation areas,[6] which include much of Richmond Hill.[7] A specific Act of Parliament protects the scenic view of the River Thames from Richmond.[8]

| Richmond | |

|---|---|

Richmond Riverside | |

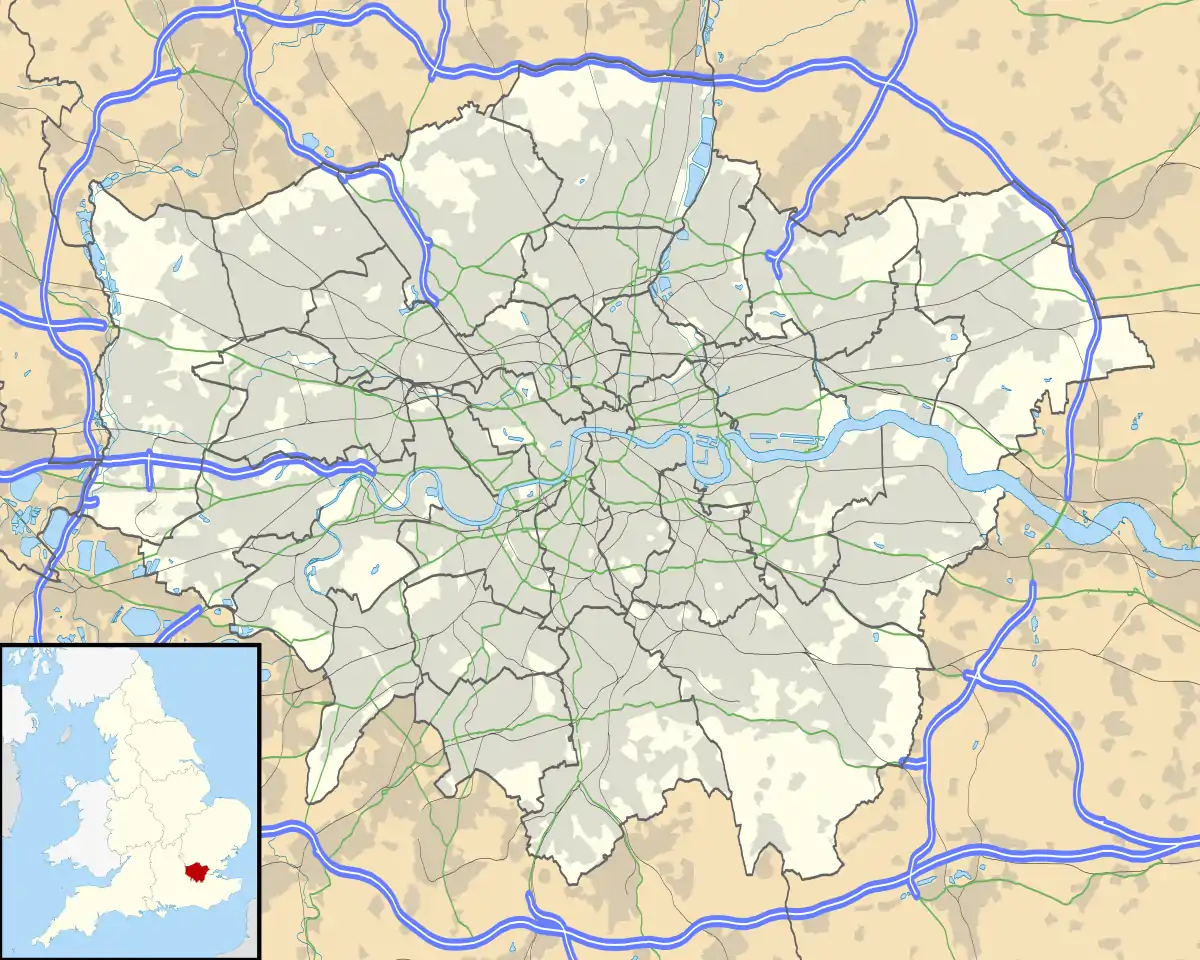

Richmond Location within Greater London | |

| Area | 5.38 km2 (2.08 sq mi) |

| Population | 21,469 (North Richmond and South Richmond wards 2011)[1] |

| • Density | 3,991/km2 (10,340/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TQ1874 |

| • Charing Cross | 8.2 mi (13.2 km) ENE |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | RICHMOND |

| Postcode district | TW9, TW10 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Richmond was founded following Henry VII's building of Richmond Palace in the 16th century, from which the town derives its name. (The palace itself was named after Henry's earldom of Richmond, North Yorkshire.) During this era the town and palace were particularly associated with Elizabeth I, who spent her last days there. During the 18th century Richmond Bridge was completed and many Georgian terraces were built, particularly around Richmond Green and on Richmond Hill. These remain well preserved and many have listed building architectural or heritage status. The opening of the railway station in 1846 was a significant event in the absorption of the town into a rapidly expanding London.

Richmond was formerly part of the ancient parish of Kingston upon Thames in the county of Surrey. In 1890 the town became a municipal borough, which was later extended to include Kew, Ham, Petersham and part of Mortlake (North Sheen).[9] The municipal borough was abolished in 1965 when, as a result of local government reorganisation, Richmond was transferred from Surrey to Greater London.[10]

Richmond is now part of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, and has a population of 21,469 (consisting of North Richmond and South Richmond wards). It has a significant commercial and retail centre with a developed day and evening economy. The name Richmond upon Thames is often used, incorrectly, to refer to the town of Richmond: in fact (unlike nearby Kingston upon Thames), the suffix should properly be used only in reference to the London Borough.

History

Name

The area was known in the medieval period as Shene, a name first recorded (as Sceon) in the 10th century, and which survives in the neighbouring districts of East Sheen (also known as Sheen) and North Sheen. The manor entered royal hands, and the manor house eventually became known as Sheen Palace, before being largely destroyed by fire in 1497. Henry VII rebuilt it, and in 1501 named it Richmond Palace in allusion to his earldom of Richmond and his ancestral honour of Richmond in Yorkshire. The associated settlement took the same name, although for some years the two names were often used in conjunction (for example, "Shene otherwise called Richemount").[11][12]

Royal residence

Henry I lived briefly in the King's house in "Sheanes". In 1299 Edward I, the "Hammer of the Scots", took his whole court to the manor house at Sheen, a little east of the bridge and on the riverside, and it thus became a royal residence; William Wallace was executed in London in 1305, and it was in Sheen that the Commissioners from Scotland went down on their knees before Edward.

Edward II, following his defeat by the Scots at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, founded a monastery for Carmelites at Sheen. When the boy-king Edward III came to the throne in 1327 he gave the manor to his mother Isabella. Edward later spent over £ 2,000 on improvements, but in the middle of the work Edward himself died at the manor, in 1377. Richard II was the first English king to make Sheen his main residence, which he did in 1383. Twelve years later Richard was so distraught at the death of his wife Anne of Bohemia at the age of 28 that, according to Holinshed, the 16th-century English chronicler, he "caused it [the manor] to be thrown down and defaced; whereas the former kings of this land, being wearie of the citie, used customarily thither to resort as to a place of pleasure, and serving highly to their recreation". It was rebuilt between 1414 and 1422, but destroyed by fire in 1497.[13]

Following that fire Henry VII built a new residence at Sheen and in 1501 he named it Richmond Palace. The theatre company to which Shakespeare belonged performed some plays there during the reign of Elizabeth I.[14] As Queen, Elizabeth spent much of her time at Richmond, as she enjoyed hunting stags in the "Newe Parke of Richmonde" (now Old Deer Park). She died at the palace on 24 March 1603.[15] The palace was no longer in residential use after 1649, but in 1688 James II ordered its partial reconstruction: this time as a royal nursery. The bulk of the palace had decayed by 1779; but surviving structures include the Wardrobe, Trumpeters' House (built around 1700), and the Gate House, built in 1501. This has five bedrooms and was made available on a 65-year lease by the Crown Estate Commissioners in 1986.

18th- and 19th-century development

Beyond the grounds of the old palace, Richmond remained mostly agricultural land until the 18th century. White Lodge, in the middle of what is now Richmond Park, was built as a hunting lodge for George II and during this period the number of large houses in their own grounds – such as Asgill House and Pembroke Lodge – increased significantly. These were followed by the building of further important houses including Downe House, Wick House and The Wick on Richmond Hill, as this area became an increasingly fashionable place to live. Richmond Bridge was completed in 1777 to replace a ferry crossing that connected Richmond town centre on the east bank with its neighbouring district of East Twickenham. Today, this, together with the well-preserved Georgian terraces that surround Richmond Green and line Richmond Hill to its crest, now has listed building status.[16]

As Richmond continued to prosper and expand during the 19th century, much luxurious housing was built on the streets that line Richmond Hill, as well as shops in the town centre to serve the increasing population. In July 1892 the Corporation formed a joint-stock company, the Richmond (Surrey) Electric Light and Power Company, and this wired the town for electricity by around 1896.

World Wars

Like many other large towns in Britain, Richmond lost many young people in the First and Second World Wars. In the Second World War, 96 people were killed in air raids, which also resulted in the demolition of 297 houses.[17] The Richmond War Memorial, which now commemorates both wars, was installed in 1921 at the end of Whittaker Avenue, between the Old Town Hall and the Riverside.[18]

Governance

Current

The town of Richmond is in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames and forms part of the Richmond Park constituency for the UK Parliament. The Member of Parliament, elected in 2019, is Sarah Olney for the Liberal Democrats. Richmond is also part of the South West constituency for the London Assembly.

Historical

Richmond, earlier known as Shene, was part of the large ancient parish of Kingston upon Thames in the Kingston hundred of Surrey. Split off from Kingston upon Thames from an early time, the parish of Richmond St Mary Magdalene formed the Municipal Borough of Richmond from 1890.[19] The municipal borough was expanded in 1892 by the addition of Kew, Petersham and the North Sheen part of Mortlake;[9] in 1933 Ham was added to the borough.[9] In 1965 the parish and municipal borough were abolished by the London Government Act 1963, which transferred Richmond to Greater London. Together with the former Municipal Borough of Twickenham and the Municipal Borough of Barnes it formed a new borough, the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames.[20]

Geography

Click to enlarge.

Richmond sits opposite East Twickenham on what is technically the south bank of the River Thames, but owing to the way this stretch of the river's meanders, the town is immediately north and north-east of its nearest stretch of river. The Thames curves around the town, and then Kew, in its course; starting from Petersham it reverts to a more definitively west–east axis. The river is still tidal at Richmond, so to allow major passenger and goods traffic to continue to operate during low tide, a half-tide lock was opened in 1894 and is used when the adjacent weir is in position. This weir ensures that there is always a minimum depth of water of 5 ft. 8in. (1.72 m) toward the middle of the river between Richmond and Teddington whatever the state of the tide. Above the lock and weir there is a small footbridge.

Richmond is well endowed with green and open spaces accessible to the public. At the heart of the town sits Richmond Green, which is roughly square in shape and together with the Little Green, a small supplementary green stretching from its southeast corner, is 12 acres (0.05 km2) in size. The Green is surrounded by well-used metalled roads that provide for a fair amount of vehicle parking for both residents and visitors. The south corner leads into the main shopping area of the town; at the west corner is the old gate house which leads through to other remaining buildings of the palace; at the north corner is pedestrian access to Old Deer Park (plus vehicle access for municipal use). The park is a 360-acre (1.5 km2) Crown Estate landscape extending from the town along the riverside as far as the boundary with the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This contains wide green lawns and sports facilities, and the Grade I listed former King's Observatory erected for George III in 1769. The town's main shopping street, George Street, is also named after the king.[21][22]

The town centre lies just below 33 ft (10m) above sea level. South of the town centre, rising from Richmond Bridge to an elevation of 165 ft (50m), is Richmond Hill. To its south rises Richmond Park, an area of 2,360 acres (9.55 km2; 3.7 sq mi) of wild heath and woodland originally enclosed for hunting, and now forming London's largest royal park.[23] The park is a national nature reserve,[24] a Site of Special Scientific Interest[25][26] and a Special Area of Conservation[27] and is included, at Grade I, on Historic England's Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of special historic interest in England.[28] It was created by Charles I in 1634[29] as a deer park and now has 630 red and fallow deer.[30] The park has a number of traffic and pedestrian gates leading to the surrounding areas of Sheen, Roehampton, Putney, Kingston and Ham.

Economy

The London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, of which Richmond North and South make up two of its wards, has the least poverty in London.[31] The town of Richmond has the largest commercial centre in the borough and is classified a major centre according to the London Plan. It is an established up-market shopping destination.[32] Its compact centre has approximately 50,000m2 of retail floor-space that is largely focused on George Street, The Quadrant and Hill Street. It comprises almost exclusively high street chains, the largest of which are Marks & Spencer, Boots, Tesco Metro and Waitrose. A Whole Foods Market with 20,000 ft2 of floor space within a new development opened in 2013.[33] The remaining town centre stores are largely single units.

Mostly independent businesses line the narrow alleyways running off George Street towards Richmond Green and up Richmond Hill and there is a farmers' market in Heron Square on Saturdays. Richmond has one large stand-alone supermarket, Sainsbury's, with parking for 420 cars to the east of the town, near North Sheen railway station.

A range of convenience shopping, restaurants and cafes can be found on the crest of Richmond Hill lining Friars Stile Road, as well as along Kew Road towards the Botanical Gardens, and on Sheen Road, which comprise the third tier of the shopping hierarchy.

Richmond also offers a wide variety of office accommodation and is the UK/European headquarters of several multi-national companies including eBay, PayPal and The Securitas Group, as well as head office to a number of national, regional and local businesses. London's Evening Standard has described Richmond as "the beating heart of London's growing technology industry".[34]

Places of interest

Richmond Riverside

The Thames is a major contributor to the interest that Richmond inspires in many people. It has an extensive frontage around Richmond Bridge, containing many bars and restaurants. The area owes much of its Georgian style to the architect Quinlan Terry who was commissioned to restore the area (1984–87). Within the river itself at this point are the leafy Corporation Island and the two small Flowerpot Islands. The Thames-side walkway provides access to residences, pubs and terraces, and various greens, lanes and footpaths through Richmond. The stretch of the Thames below Richmond Hill is known as Horse Reach, and includes Glover's Island. There are towpaths and tracks along both sides of the river, and they are much used by pedestrians, joggers and cyclists. Westminster Passenger Services Association boats, licensed by London River Services, sail daily between Westminster Pier and Hampton Court Palace, calling at Richmond in each direction.

Richmond Green

Richmond Green, which has been described as "one of the most beautiful urban greens surviving anywhere in England",[35] is essentially square in shape and its open grassland, framed with broadleaf trees, extends to roughly twelve acres. On summer weekends and public holidays the Green attracts many residents and visitors. It has a long history of hosting sporting events; from the 16th century onwards tournaments and archery contests have taken place on the green, while cricket matches have occurred since the mid 18th century,[36] continuing to the present day. Until recently, the first recorded inter-county cricket match was believed to have been played on Richmond Green in 1730 between Surrey and Middlesex. It is now known, however, that an earlier match between Kent and Surrey took place in Dartford in 1709.[37]

To the west of the Green is Old Palace Lane running gently down to the river. One of the oldest roads in Richmond, it was originally a route from the river, where goods were loaded and unloaded by crane, to the "tradesman's entrance" to Richmond Palace.[38] Adjoining to the left is the renowned terrace of well-preserved three-storey houses known as Maids of Honour Row. These were built in 1724 for the maids of honour (trusted royal wardrobe servants) of Queen Caroline, the queen consort of George II. As a child, Richard Burton, the Victorian explorer, lived at number 2.[39]

Today the northern, western and southern sides of the Green are residential while the eastern side, linking with George Street, is largely retail and commercial. Public buildings line the eastern side of the Little Green and pubs and cafés cluster in the corner by Paved Court and Golden Court – two of a number of alleys that lead from the Green to the main commercial thoroughfare of George Street. These alleys are lined with mostly privately owned boutiques.

Richmond Hill

Partway up Richmond Hill is the Poppy Factory, staffed mainly by disabled ex-servicemen and women, which produces the remembrance poppies sold each November for Remembrance Day.

The view from the top westward to Windsor has long been famous, inspiring paintings by masters such as J. M. W. Turner and Sir Joshua Reynolds[8] and also poetry.[8] One particularly grand description of the view can be found in Sir Walter Scott's novel The Heart of Midlothian (1818). It is a common misconception that the folk song "Lass of Richmond Hill" relates to this hill, but the young woman in the song lived in Hill House at Richmond in the Yorkshire Dales.[40]

Apart from the great rugby stadium at Twickenham and the aircraft landing and taking off from Heathrow, the scene has changed little in two hundred years. The view from Richmond Hill now forms part of the Thames Landscape Strategy which aims to protect and enhance this section of the river corridor into London.[41]

A broad, gravelled walk runs along the crest of the hill and is set back off the road, lined with benches, allowing pedestrians an uninterrupted view across the Thames valley with visitors' information boards describing points of interest. Sloping down to the River Thames are the Terrace Gardens that were laid out in the 1880s and were extended to the river some 40 years later.[42]

A commanding feature on the hill is the former Royal Star and Garter Home; in the 2010s it was sold for development and converted into residential apartments. During World War I an old hotel on this site, the Star and Garter, which had been a popular place of entertainment in the 18th and 19th centuries but had closed in 1906, was taken over and used as a military hospital.[43] After the war it was replaced by a new building providing accommodation and nursing facilities for 180 seriously injured servicemen. This was sold in 2013 after the charitable trust running the home concluded that the building no longer met modern requirements and could not be easily or economically upgraded. The trust opened an additional home in Solihull, West Midlands, and the remaining residents in Richmond moved in 2013 to a new purpose-built building in Surbiton.[44]

Richmond Park

At the top of Richmond Hill, opposite the former Royal Star and Garter Home, sits the Richmond Gate entrance to Richmond Park. The park is a national nature reserve, a Site of Special Scientific Interest, and a Special Area of Conservation. The largest of London's Royal Parks, it was created by Charles I in 1634 as a deer park and now has over 600 red and fallow deer. Richmond Gate remains open to traffic between dawn and dusk.

King Henry's Mound, a Grade II listed[45] Neolithic burial barrow,[46] is the highest point within the park. From the mound, there is a protected view of St Paul's Cathedral in the City of London over 10 miles (16 km) to the east which was established in 1710. At various times the mound's name has been connected with Henry VIII or with his father Henry VII.[46] However, there is no evidence to support the legend that Henry VIII stood on the mound to watch for the sign from St Paul's that Anne Boleyn had been executed at the Tower and that he was then free to marry Jane Seymour.[46]

King Henry's Mound is in the grounds of Pembroke Lodge, which is Grade II listed.[47] In 1847 this house became the home of the then Prime Minister, Lord John Russell,[48] who conducted much government business there and entertained Queen Victoria, foreign royalty, aristocrats, writers (Dickens, Thackeray, Longfellow, Tennyson) and other notable people of the time, including Garibaldi. It was later the childhood home of Lord John Russell's grandson, the philosopher, mathematician and social critic Bertrand Russell. It is now a popular restaurant with views across the Thames Valley.

Also in the park and Grade II listed is Thatched House Lodge, a royal residence. Since 1963 it has been the home of Princess Alexandra, The Honourable Lady Ogilvy, a cousin of Queen Elizabeth II. During the Second World War it was the home of General Dwight D Eisenhower, who later became President of the United States.[49]

Museums and galleries

The Museum of Richmond, in Richmond's Old Town Hall, close to Richmond Bridge, has displays relating to the history of Richmond, Ham, Petersham and Kew. Its rotating exhibitions,[50] education activities and a programme of events cover the whole of the modern borough. The museum's highlights include 16th-century glass from Richmond Palace and a painting, The Terrace and View from Richmond Hill, Surrey by Dutch draughtsman and painter Leonard Knyff (1650–1722), which is part of the Richmond upon Thames Borough Art Collection.[51] Admission to the museum is free.[52]

The Riverside Gallery, also at the Old Town Hall, has a year-round programme of exhibitions by local artists including paintings, prints and photographs. Admission is free.

Theatres and cinemas

Richmond has two theatres. The Richmond Theatre on Little Green is a late Victorian structure designed by Frank Matcham and restored and extended by Carl Toms in 1990. The theatre has a weekly schedule of plays and musicals, usually given by professional touring companies, and pre-West End shows can sometimes be seen. There is a Christmas and New Year pantomime tradition and many of Britain's greatest music hall and pantomime performers have appeared here.

Close to Richmond railway station is the Orange Tree Theatre which was founded in 1971 in a room above the Orange Tree pub. As audience numbers increased there was pressure to find a more accommodating space and, in 1991, the company moved to its current premises within a converted primary school. The 172-seat theatre was built specifically as a theatre in the round. Exclusively presenting its own productions, it has acquired a national reputation for the quality of its work for staging new plays, and for discovering undeservedly forgotten old plays and neglected classics.[53]

The town has two cinemas, the arthouse Curzon in Water Lane and an Odeon cinema with a total of seven screens in two locations, the foyer of one having the accolade of being the only high street building visible from Richmond Bridge, and the second set being situated nearby in Red Lion Street.

Pubs and bars

Numerous public houses and bars scattered throughout Richmond's town centre, and along the river and up the hill, with enough variety to cater to most tastes. One of the oldest is The Cricketers, serving beer since 1770, though the original building was burned down in 1844. It was soon replaced by the present building shown here. Samuel Whitbread, founder of Whitbread Brewery, part-owned it with the Collins family who had a brewery in Water Lane, close to the old palace.[54] Grade II listed pubs include the White Cross,[55] the Old Ship[56] and the Britannia.[57]

Restaurants and cafes

Many of the major restaurant chains can be found within 500 metres of Richmond Bridge. There are also plenty of privately owned restaurants with culinary offerings from around the world, including French, German, Indian, Japanese, Korean, Russian, Spanish and Thai.

The Bingham Riverhouse hotel[58] was awarded its first Michelin star in 2010.[59] The hotel, which overlooks the Thames, is in a Grade II listed building that dates from about 1760.[60]

Societies

| |

| Abbreviation | RLHS |

|---|---|

| Motto | Exploring the history of Richmond, Kew, Petersham and Ham |

| Formation | 1985[nb 2] |

| Founder | John Cloake |

| Legal status | registered charity (number 292907)[61] |

Region served | Richmond, Kew, Petersham and Ham[61] |

Membership | 400 |

Chairman | Robert Smith[62] |

Main organ | Richmond History (annual journal); The Richmond Local History Society Newsletter (three times a year) |

Budget | <£11,000[63] |

Staff | none |

| Website | richmondhistory |

| Motto | For people who love Richmond |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1957 |

| Type | civic society and conservation group |

| Legal status | charitable incorporated organisation (number 1169079)[61] |

Region served | Richmond, Kew, Petersham and Ham[61] |

Membership | 1300 |

Chairman | Barry May |

Main organ | The Richmond Society Quarterly Newsletter[64] |

Budget | £41,116[61] |

Staff | none |

| Website | richmondsociety |

The Richmond Local History Society explores the local history of Richmond, Kew, Petersham and Ham. It organises a programme of talks on historical topics[65] and visits to buildings of historical interest.[66] The Society publishes a newsletter three times a year, an indexed annual journal (Richmond History) and other publications.[67]

The Richmond Society is a civic society and conservation group which was founded in 1957 by a group of local residents, originally to fight against the proposal to install modern lamp posts around Richmond Green. It acts as a pressure group concerned with preserving Richmond's natural and built environment, monitoring and influencing development proposals and presenting annual awards[68][69] for buildings and other schemes which make a positive contribution to Richmond. It also organises meetings on topics of local interest and a programme of guided walks and visits, and publishes a quarterly newsletter.[64][70] Professor Ian Bruce CBE, Bamber Gascoigne CBE FRSL, Sir Trevor McDonald OBE, Ronny, Baroness van Dedem and Lord Watson of Richmond CBE[71] are the Society's patrons.

Richmond Opera (formerly Isleworth Baroque) holds rehearsals in Richmond and gives performances in the local area.[72][73]

Leisure activities

With a third of the borough being green and open space – five times more than any other borough in London –[74] Richmond has much to offer in the way of leisure activities.

Field sports

In Old Deer Park the Pools on the Park leisure centre, run by the borough council, includes 33m indoor and outdoor pools and a fitness centre. Nearby, the park also provides open recreation areas, football, rugby and other pitches; in addition there is the Richmond Athletic Ground, home to Richmond F.C. and London Scottish rugby clubs. An additional sports ground is home to both the Richmond Cricket Club and the London Welsh Rugby Union club, as well as tennis courts and a bowling green. The Royal Mid-Surrey Golf Club[75] is also there with both golf and pitch and putt courses.

The Prince's Head Cricket Club holds fixtures on Richmond Green throughout the summer.[76]

Cycling

Richmond is part of the London Cycle Network, offering on and off-road cycle paths throughout the area, including along the Thames Towpath and in Richmond Park.[77]

Equestrian

Richmond Park also has bridle paths and horses can be rented from a number of stables around the perimeter of the park.[78]

Ham Polo Club is on the Petersham Road at the bottom of Richmond Hill. The club was established in 1926 and is now the only polo club in London; it is popular with picnickers during the summer months.[79]

Boating

Skiffs (fixed seat boats) can be hired by the hour from local boat builders close to the bridge, with opportunities to row upstream towards the historic properties Ham House and Marble Hill House. In addition, Richmond Canoe Club,[80] founded in 1944 and now Britain's biggest canoe club, is also on the towpath south of Richmond Bridge.

Education

Richmond University – a private institution, also known as Richmond, the American International University in London – is based here. Its degrees are accredited in the US and validated in the UK.

Demography and housing

| Ward | Detached | Semi-detached | Terraced | Flats and apartments | Caravans/temporary/mobile homes/houseboats | Shared between households[81][1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Richmond | 142 | 1,093 | 1,546 | 1,963 | 0 | 27 |

| South Richmond | 384 | 653 | 1,092 | 2,995 | 0 | 44 |

| Ward | Population | Households | % Owned outright | % Owned with a loan | hectares[81] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Richmond | 10,649 | 5,168 | 26 | 30 | 272 |

| South Richmond | 10,820 | 4,047 | 28 | 24 | 266 |

In 2011, Richmond was 66.5% White British, 1.2% Black, 6.3% Asian, 3.5% Mixed and 18.6% Other White.

German residents

The town and the borough of Richmond have been popular destinations for German expatriates and German British since at least the 19th century. The German-born businessman Sir Max Waechter donated Glover's Island to the local council in 1900. The German School London opened in nearby Petersham in 1971, continuing the popularity of Richmond for German families settling in London.[82]

Transport

Thirty per cent of Richmond households do not have a car or van. This figure is well above the borough average of 24% which may be related to the excellent transport links in the area and the lower proportion of families as reported in the 2001 census. A half of households have one car in line with the borough average.[83]

Tube/trains

- Richmond station

- District line towards Kew Gardens and Upminster

- London Overground towards Kew Gardens, Willesden Junction and Stratford

- Waterloo to Reading line and three branch line services call at the station en route to Windsor and Weybridge. One service calls at Richmond station on its return to the central London terminus via Kingston upon Thames

- North Sheen station

- Waterloo to Reading line

Buses

London Buses routes 33, 65, 190, 337, 371, 419, 490, 493, H22, H37, R68, R70, N22 and N65 serve Richmond.

Roads

Richmond's main arterial road, the A316, running between Chiswick and the M3 motorway, bisects Old Deer Park and the town to its north. The town's only dual carriageway, it was built in the 1930s, cutting off Richmond from Kew and entailing the construction of Twickenham Bridge. This road expands into three lanes and motorway status three and five miles west respectively.

The town centre is on the A307, which used to be the main link between London and north-west Surrey, and was previously one of the main routes of the Portsmouth Road before that was diverted.

Nearest hospitals

- Richmond Royal Hospital, on Kew Foot Road in Richmond, is a mental health facility operated by South West London and St George's Mental Health NHS Trust.

- Queen Mary's Hospital, Roehampton is a community hospital in Roehampton in the London Borough of Wandsworth. It is run by St George's University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

The nearest acute hospitals, both of which include accident & emergency units and maternity units, are:

- Kingston Hospital in Kingston upon Thames, which is managed by the Kingston Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

- West Middlesex Hospital in Isleworth, which is operated by the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Places of worship

Almshouses

Richmond has eight groups of almshouses. They are all managed by Richmond Charities, which also manages Candler Almshouses in Twickenham. Six are of historical interest and some were founded in the 16th century:

| Name | Address | Number | History | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bishop Duppa's Almshouses | The Vineyard | 10 almshouses | The original almshouses were founded in 1661 (on Richmond Hill) by Brian Duppa, Bishop of Winchester. They were rebuilt in 1851 on the present site and are Grade II listed. |  |

| Church Estate Almshouses | Sheen Road | 10 almshouses | Most of the buildings, designed by William Crawford Stow and now Grade II listed, date from 1843 but the charity that built them is known to have existed in Queen Elizabeth I's time and may have much earlier origins. | .jpg.webp) |

| Hickey's Almshouses | Between Sheen Road and St Mary's Grove | 50 almshouses | William Hickey, who died in 1727, left the income of several properties on Richmond Hill in trust to provide pensions for six men and ten women. In 1822 the charity's funds were boosted by a major donation by Elizabeth Doughty. Twenty almshouses, designed by Lewis Vulliamy, and a chapel and two gate lodge cottages, were built in 1834 and are Grade II* listed. The property, which includes another 29 buildings behind the almshouses, now consists of 49 flats and cottages, a laundry and a workshop. |  |

| Houblon's Almshouses | Worple Way | 9 almshouses | Now Grade II* listed, these were founded in 1757 by Rebecca and Susanna Houblon (who built nine almshouses). A further two almshouses were added in 1857. |  |

| Michel's Almshouses | The Vineyard | 17 almshouses | These were founded in the 17th century by Humphrey Michel. The original ten almshouses were built in 1696 and were rebuilt in 1811. Another six almshouses were added in 1858. They are Grade II listed. |  |

| Queen Elizabeth's Almshouses | The Vineyard | 4 almshouses | These were founded by Sir George Wright in 1600 (during the reign of Elizabeth I) to house eight poor aged women. Known originally as the "Lower almshouses", they were built in Petersham Road, a few hundred yards south of what is now Bridge Street. By 1767, they were almost derelict. In 1767, William Turner rebuilt the almshouses on land at the top end of his estate in The Vineyard. Funds for the rebuilding were raised by public subscription. The almshouses were rebuilt again in 1857. They were damaged during World War II and replaced with four newly built houses in 1955. |  |

A seventh set of almshouses, Benn's Walk (now with five almshouses), was built in 1983.[84]

An eighth set of almshouses is 10–18 Manning Place (with nine almshouses), just off Queen's Road. The property was built in 1993 and was purchased by The Richmond Charities in 2017.[85]

Local newspapers

The Richmond and Twickenham Times has been published since 1873.[86] The Twickenham & Richmond Tribune, a weekly online newspaper, has been published since 2016.[87]

Notable residents

For centuries, Richmond was home to the country's royal family. It also has a long list of famous residents, both past and present.

- List of current and former residents of Richmond upon Thames

Film locations

Richmond is a popular filming location. Richmond Park has featured in many films and TV series.

- A locomotive runs through the park and crashes into a tree in the film The Titfield Thunderbolt (1955).[88]

- In the 1968 film Performance, James Fox crosses Richmond Park in a Rolls-Royce car.[88]

- The park was the backdrop for the classic historical film Anne of the Thousand Days (1969),[89] with Richard Burton and Geneviève Bujold, which looks back to Richmond Park in the 16th century. The film tells the story of King Henry VIII's courtship of Anne Boleyn and their brief marriage.

- An Indian dust storm was filmed in the park for the film Heat and Dust (1983).[88]

- The Royal Ballet School in Richmond Park featured in the film Billy Elliot (2000).[88][90]

- In 2010, director Guy Ritchie filmed parts of Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows in the park with Robert Downey, Jr. and Jude Law.[91]

- Some of the scenes from Into the Woods (2014), the Disney fantasy film featuring Meryl Streep,[92] were filmed in the park.[93][94]

As well as a location for films, Richmond Park is regularly featured in television programmes, corporate videos and fashion shoots. It has made an appearance on Blue Peter, Inside Out (the BBC regional current affairs programme) and BBC Springwatch.[89] In 2014 it was featured in a video commissioned by The Hearsum Collection[95] and in 2017 in a television film featuring and narrated by David Attenborough, which was produced by the Friends of Richmond Park.[96]

The village green, divided into The Green and Little Green, has Georgian splendour, stately listed buildings and paved alleyways leading to the high street. It is a magnet for film crews, particularly when recreating a city square or row of townhouses of bygone years. In 2011, The Crimson Petal and the White was filmed there,[97] as was Downton Abbey in July 2014.[98] Many other films and TV shows have featured The Green or Little Green, including Agatha Christie's Poirot.[99] Simon Schama's Power of Art, Peter Rabbit 2[100] and the 2020 sports comedy TV series Ted Lasso.[101]

Richmond Theatre ranks as a major film location; it has featured in the Peter Sellers comedy The Naked Truth (1957),[102] Bugsy Malone (1976), The Krays (1990), Evita (1996), Bedazzled (2000), The Hours (2002), Finding Neverland (2004)[103] and The Wolfman (2010).[104]

Notes

- The London Government Act 1963 (c.33) (as amended) categorises the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames as an Outer London borough. Although it is on both sides of the River Thames, the Boundary Commission for England defines it as being in South London or the South Thames sub-region, pairing it with Kingston upon Thames for the purposes of devising constituencies. However, for the purposes of the London Plan, Richmond now lies within the West London region.

- The Society originated as the History and Archaeology Section of The Richmond Society, launched in April 1975. It became an independent society in 1985.

Cloake, John (July 2014). "Forty Years of Richmond History". Richmond Local History Society. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

References

- Census Information Scheme (2012). "2011 Census Ward Population Estimates". Greater London Authority. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "London Government Act 1963 (c.33) (as amended)". Office of Public Sector Information. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "London Initial proposals summary" (PDF). Boundary Commission for England. September 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- Fifth Periodical Report Cm 7032B (PDF). Boundary Commission for England. March 2007. ISBN 9780101703222. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Mayor of London (April 2009). "A new plan for London: Proposals for the Mayor's London Plan" (PDF). Greater London Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "Conservation Areas" (PDF). London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- "Richmond Hill Conservation Area 5" (PDF). London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- Richmond Libraries' Local Studies Collection (22 October 2020). "Preservation of the View". The view from Richmond Hill. London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, Richmond MB (historic map). Retrieved {{{accessdate}}}.

- Young, K. & Garside, P. (1982). Metropolitan London: Politics and Urban Change 1837–1981. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 9780713163315.

- "Richmond", in Encyclopædia Britannica, (9th edition, 1881), s.v.

- Gover, J. E. B.; Mawer, A.; Stenton, F. M. (1934). The Place-Names of Surrey. English Place-Name Society. 11. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 65–66.

- Goringe, Marcus (12 July 2016). "Richmond: the lost palace". The National Archives (United Kingdom). Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "Richmond Palace". London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Local History notes. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Black, J. B. (1945) [1936]. The Reign of Elizabeth: 1558–1603. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 410–411. OCLC 5077207.

- "List of buildings of special architectural or historic interest" (PDF). London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- Fowler, Simon (2015). Richmond at War 1939–1945. Richmond Local History Society. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-9550717-8-2.

- Historic England (20 July 2017). "Richmond upon Thames Borough War Memorial (1447856)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, Richmond parish (historic map). Retrieved {{{accessdate}}}.

- "London Government Act 1963". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Dunbar, Janet. A Prospect of Richmond (1977 ed.). George G. Harrap and Co. pp. 199–209. ISBN 9780856179952.

- The Streets of Richmond and Kew (Third ed.). Richmond Local History Society. 2019. p. 46.

- "Map of Richmond Park". The Royal Parks. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- "London's National Nature Reserves". Natural England. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- "Richmond Park" (PDF). Citation. Natural England. 1992. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- "Map of Richmond Park SSSI". Natural England. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- "Richmond Park". Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- Historic England (1 October 1987). "Richmond Park (1000828)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- Historic England (2015). "Richmond Park (397979)". PastScape. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- "Deer in Richmond Park". The Royal Parks. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Department for Work and Pensions Archived 2 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine 2001 Census statistics. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- "Richmond". Business: Property and sites. London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Butler, Sarah (27 February 2015). "Whole Foods Market halves its UK losses". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- "Richmond revealed as new tech hotspot". Evening Standard. 21 October 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- Cherry, Bridget and Pevsner, Nikolaus (1983). The Buildings of England – London 2: South. London: Penguin Books. p. 521. ISBN 978-0-14-0710-47-2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Richmond Libraries' Local Studies Collection (10 February 2020). "Richmond Green properties". London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- CricketArchive

- Robinson, Derek; Fowler, Simon (2020). Old Palace Lane: Medieval to Modern Richmond (2nd ed.). Richmond Local History Society and Museum of Richmond. ISBN 978-1-912-314027.

- "Sir Richard Burton (1821–1890) and Lady Isabel Burton (1831–1896)". Local history notes. London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. 8 July 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- "The Lass of Richmond Hill". I'Anson International. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- "Thames Landscape Strategy". Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Historic England (24 August 2002). "Terrace and Buccleuch Gardens (1001551)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- "Royal Star and Garter Home". Lost Hospitals of London. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- Sharman, Jon (29 August 2013). "Residents move into new Royal Star and Garter home in Surbiton". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- Historic England (27 May 2020). "King Henry VIII's Mound, Richmond Park (1457267)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- Cloake, John (2014). "'Sheene Chase' and 'King Henry VIII's Mound': two incorrect myths concerning Richmond Park". Richmond History: The Journal of Richmond History Society. 35: 38–40.

- Historic England (25 May 1983). "Pembroke Lodge (1263437)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- Fletcher Jones, Pamela (1972). Richmond Park: Portrait of a Royal Playground. Phillimore & Co Ltd. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-8503-3497-5.

- Weinreb, Ben; et al. (1983). "Thatched House Lodge". The London Encyclopaedia. London: Macmillan. p. 914. ISBN 978-1-4050-4924-5.

- Farquharson, Hannah (7 April 2006). "Elizabeth I letter among museum gems". Richmond and Twickenham Times. London. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- "The Terrace and View from Richmond Hill, Surrey". Art UK. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Museum of Richmond". Visit London. London & Partners. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- "About Us". Orange Tree Theatre. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Richmond Green properties: Brewers Lane to Paved Court (Greenside) Local history notes, 22 October 2020, London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- Historic England (25 May 1983). "White Cross Hotel (1250279)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- Historic England (25 June 1983). "Old Ship public house (1286531)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- Historic England (25 June 1983). "Britannia public house (1358054)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- Bingham Riverhouse

- "The full list of 2010 Michelin star restaurants in the UK". Design Restaurants. 11 February 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- Historic England (10 January 1950). "Bingham House Hotel (1065332)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "Find charities". Charity Commission. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- "Merry Christmas to all Richmond and Twickenham Times readers". Richmond and Twickenham Times. 25 December 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- "Richmond Local History Society". Charity Commission. 31 December 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- "Newsletter". The Richmond Society. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Cox, Laura (8 March 2015). "Richmond Local History Society jazzing things up for new talk". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- Hébert, Gail (15 January 2009). "Richmond's Victorian Gothic gem". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "The Richmond Local History Society". website. Richmond Local History Society. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- "Richmond Society hands out yearly good, the bad, and the ugly awards". Richmond and Twickenham Times. 31 October 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- "Royal Park wins Richmond Society Award". The Royal Parks. 19 October 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- "The Richmond Society". The Richmond Society. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- "Sir Trevor McDonald joins our distinguished group of Patrons" (PDF). The Richmond Society Quarterly Newsletter (236). Winter 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2013.

- "About Richmond Opera". Richmond Opera. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "Isleworth Baroque". Richmond Opera. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "Parks in Richmond". Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Totally Richmond. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- Royal Mid-Surrey Golf Club

- Plummer, Iain. "Prince's Head CC". www.playerwanted.co.uk. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "Cycling in Richmond". VisitRichmond. London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Horse Riding in Richmond". Totally Richmond. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- "Nostalgia: Polo's glamorous survivor in Ham". Richmond and Twickenham Times. 4 September 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Richmond Canoe Club

- "Neighbourhood statistics". Office for National Statistics.

- Moore, Fiona (2012). "The German School in London, UK: Fostering the Next Generation of National Cosmopolitans?" (Chapter 4) in Coles, Anne and Fechter, Anne-Meike (editors). Gender and Family Among Transnational Professionals (Routledge International Studies of Women and Place). Routledge. ISBN 1134156200, 9781134156207

- GLA Intelligence (January 2014). "2011 Census snapshot: Car and Van Availability" (PDF). Census Information Scheme: 14.

- "Benn's Walk Almshouses". Richmond Charities. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Manning Place". Richmond Charities. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "History of the Richmond & Twickenham Times". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "Twickenham & Richmond Tribune". Twickenham & Richmond Tribune. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- Barber, Sue; Heath, Phillippa (2009). Boyes, Valerie (ed.). Richmond on Screen: Feature Films Shot in the Borough. Museum of Richmond. p. 27.

- "Richmond Park in film". About Richmond Park. The Royal Parks. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- Lydall, Ross (3 February 2005). "Billy Elliot v the badgers". Evening Standard. London. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- "Richmond Park transformed into gypsy camp as Sherlock Holmes sequel starring Robert Downey Jr. as Sherlock and Jude Law as Dr Watson is filmed". Richmond and Twickenham Times. 18 October 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- Vincent, Alice (27 September 2013). "Meryl Streep in Into The Woods: first look". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- "Meryl Streep; Oscar Isaac; Sundance festival; National Trust film locations". The Film Programme. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- "Streep praises 'magical' park". Richmond and Twickenham Times. 7 February 2014.

- "The Heritage Pavilion Video". YouTube. 11 November 2004. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- Rutter, Calum (26 April 2017). "Sir David Attenborough's new film about Richmond Park asks its millions of visitors to tread lightly". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- Lewis, Sue; Hillman, Sarah (October 2010). "Richmond Stars" (PDF). Filmrichmond: 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Lewis Sue; Hillman, Sarah (November 2014). "Richmond Stars" (PDF). Filmrichmond: 2. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- "Richmond Green: Film/TV Location". VisitRichmond. London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- Krause, Riley (29 March 2019). "Peter Rabbit 2 will be filming in Richmond next week". Richmond and Twickenham Times. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- Ted Lasso (2020): Official trailer. 2020.

- Wilkinson, Phil; Tunstill, John. "Naked Truth, The". Reel Streets. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "Wednesday 18th December – Finding Neverland" (PDF). Programme of Films, Talks and Events September – December 2013. Museum of Richmond. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- Lewis, Sue; Hillman, Sarah (Summer 2008). "Richmond Stars" (PDF). Filmrichmond: 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

Further reading

- Cloake, John (1982). The Growth of Richmond. Richmond Society History Section. ISBN 978-0950819808.

- Cloake, John (1990). Richmond's Great Monastery: The Charterhouse of Jesus of Bethlehem of Shene. Richmond Local History Society. ISBN 0-9508198-6-7.

- Cloake, John (1991). Richmond Past: A Visual History of Richmond, Kew, Petersham and Ham. London: Historical Publications. ISBN 0-948667-14-1. Recounts the history of the Richmond area – including Kew, Petersham and Ham – from 1501 and is illustrated with drawings, paintings and photographs.

- Cloake, John (1995). The Palaces and Parks of Richmond and Kew 1: The Palaces of Shene and Richmond. Chichester: Phillimore & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-0850339765. OCLC 940979634.

- Cloake, John (1996). The Palaces and Parks of Richmond and Kew 2: Richmond Lodge and the Kew Palaces. Chichester: Phillimore & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-1860770234. OCLC 36045530. OL 8627654M.

- Cloake, John (2001). Cottages and Common Fields of Richmond and Kew. Chichester: Phillimore & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-1860771958.

- Cloake, John (2001). Richmond Palace: Its History and Its Plan. Richmond Local History Society. ISBN 978-0952209966.

- Fowler, Simon (2015). Richmond at War 1939–1945. Richmond Local History Society. ISBN 978-0-9550717-8-2.

- Fowler, Simon (2017). Poverty and Philanthropy in Victorian Richmond. Richmond Local History Society. ISBN 978-1-912314-00-3.

- Richmond Local History Society (Third edition, 2019). The Streets of Richmond and Kew. ISBN 978-1912-314010.

- Robinson, Derek; Fowler, Simon (Second edition, 2020). Old Palace Lane: Medieval to Modern Richmond. Richmond Local History Society and Museum of Richmond. ISBN 978-1-912-314027.

- Walford, Edward (1883). "Richmond". Greater London. London: Cassell & Co. OCLC 3009761.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Richmond, London. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for London/Richmond-Kew. |

- The Richmond Society

- Richmond Local History Society

- Royal Richmond timeline

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

.jpg.webp)