Treaty of Stettin (1630)

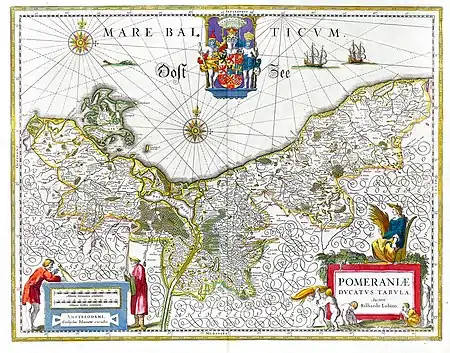

The Treaty of Stettin (Swedish: Traktaten or Fördraget i Stettin) or Alliance of Stettin (German: Stettiner Allianz) was the legal framework for the occupation of the Duchy of Pomerania by the Swedish Empire during the Thirty Years' War.[1] Concluded on 25 August (O.S.) or 4 September 1630 (N.S.), it was predated to 10 July (O.S.) or 20 July 1630 (N.S.), the date of the Swedish Landing.[nb 1][2][3] Sweden assumed military control,[2] and used the Pomeranian bridgehead for campaigns into Central and Southern Germany.[4] After the death of the last Pomeranian duke in 1637, forces of the Holy Roman Empire invaded Pomerania to enforce Brandenburg's claims on succession, but they were defeated by Sweden in the ensuing battles.[5] Some of the Pomeranian nobility had changed sides and supported Brandenburg.[6] By the end of the war, the treaty was superseded by the Peace of Westphalia (1648) and the subsequent Treaty of Stettin (1653), when Pomerania was partitioned into a western, Swedish part (Western Pomerania, thenceforth Swedish Pomerania), and an eastern, Brandenburgian part (Farther Pomerania, thenceforth the Brandenburg-Prussian Province of Pomerania).[7]

Background

Following the Capitulation of Franzburg in 1627, the Duchy of Pomerania was occupied by forces of Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor, under command of Albrecht von Wallenstein.[8] The Swedish intervention in the Thirty Years' War began with the active military support of Stralsund,[9] a Pomeranian Hanseatic port which since the Battle of Stralsund successfully resisted imperial occupation with Danish and Swedish support.[10] Sweden and Stralsund concluded an alliance scheduled for twenty years.[11] The Danish campaigns in Pomerania and other parts of the Holy Roman Empire ended with the Battle of Wolgast in 1628 and the subsequent Treaty of Lübeck in 1629.[9] Except for Stralsund, all of Northern Germany was occupied by forces of the emperor and the Catholic League.[12] In 1629, the emperor initiated the Re-Catholization of these Protestant territories by issuing the Edict of Restitution.[13]

The Truce of Altmark ended the Polish–Swedish War (1626–1629) in September 1629, releasing the military capacities needed for an invasion of the Holy Roman Empire.[9] Plans of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden for such an intervention were approved of by a Riksdag commission already in the winter of 1627/28, approval by the Riksråd followed in January 1629.[14]

On 26 June (O.S.)[15] or 6 July (N.S.) 1630,[16] Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden with a fleet of 27 ships arrived at the island of Usedom and made landfall near Peenemünde[17] with 13,000 troops[16][17] (10,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry[16] on thirteen transport ships[17]). The core of the invasion force consisted of trained peasants, recruited to the Swedish army following Gustavus Adolphus' military reforms of 1623.[nb 2][18] The western flank of the Swedish invasion force was cleared from Stralsund, which served as the basis for Swedish forces clearing Rügen and the adjacent mainland from 29 March until June 1630.[19] The officially stated Swedish motives were:

- Exclusion of Sweden from the Treaty of Lübeck (1629),[20]

- Imperial support for Poland in the Polish–Swedish War (1626–1629),[20]

- Liberation of German Protestantism,[nb 3][20]

- Restitution of German liberty.[nb 3][20]

The Swedish landing force faced Albrecht von Wallenstein's imperial occupation forces in Pomerania, commanded by Torquato Conti.[21] Large parts of the imperial army were pinned down in Italy and unable to react.[22] Wallenstein, who two years before had expelled the Danish landing forces at the same place[9] was about to be dismissed.[22] On 9 July, Swedish forces took Stettin (now Szczecin),[3] but throughout 1630 were content with establishing themselves in the Oder estuary.[17]

The treaty and amendments

The first draft of a Swedish-Pomeranian alliance, which the Pomeranian ducal councillors had worked out since 20 July 1630 (N.S.), was rejected by Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden.[3] A second draft was returned to the council together with a list of modifications Sweden insisted on.[3] On 22 August (N.S.), actual Swedish-Pomeranian negotiations started, which Gustavus Adolphus on 1 September (N.S.) joined in person.[3] The final negotiations lasted from 2–4 September (N.S.).[3]

The actual agreement was made on 25 August (O.S.)[2] or 4 September (N.S.), but pre-dated to 10 July (O.S.)[2] or 20 July 1630 (N.S.).[nb 1][3] The alliance was to be "eternal".[23] The treaty also included the alliance with Stralsund of 1628, which was concluded when the town resisted the Capitulation of Franzburg and was thus besieged by Albrecht von Wallenstein's army.[2]

Subsequent treaties were the "Pomeranian Defense Constitution"[nb 4] of 30 August 1630 (O.S.), and the "Quartering Order"[nb 5] of 1631.[2] The Swedish king and the high-ranking officers were given absolute control over the duchy's military affairs,[nb 6] while the political and ecclesial power remained with the dukes, nobles, and towns.[2] The duchy's foreign affairs were to be within the responsibility of the Swedish crown.[17] The amending treaties were necessary because the Pomeranian nobility had insisted on having the shift in military control of the duchy to Sweden separate from the Swedish-Pomeranian alliance.[3]

The Pomeranian contributions detailed in the treaties amounted to an annual 100,000 Talers.[3] Furthermore, Pomerania was obliged to supply four Swedish garrisons.[24]

The alliance

Implementation in Pomerania

When Bogislaw XIV, Duke of Pomerania had concluded the alliance, he immediately wrote a letter to Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor, reading

"This union is not directed against the majesty of the Emperor or the Empire, but is rather designed to maintain the constitution of the Empire in its ancient state of liberty and tranquillity, and to protect the religious and secular settlements[nb 3] against the ravagers and disturbers of the public peace, and thereby not only to leave intact the relationship which binds us, Bogislaw XIV [...] to His Imperial Roman Majesty [...] but also to preserve our lawful duty and obligations to the same."[25]

Bogislaw XIV further blamed the "barbarities and cruelties of the Imperial soldiers" for leaving him no choice.[26] Yet, Ferdinand II did not forgive Bogislaw XIV, and instead the imperial occupation forces in Pomerania were instructed to act even more harshly.[26] As a consequence, raids were conducted frequently, buildings and villages were burned, and the population was tormented.[26] The imperial atrocities became one argument for the Pomeranian population to support Sweden.[26] Another argument was that in contrast to Pomerania, there was no serfdom in Sweden, and thus the Pomeranian peasants held a very positive view of the Swedish soldiers, who were in fact peasants in arms.[27]

With the aforementioned treaties, Sweden included the Pomeranian duchy in her military contributions' system, enabling her to triple the size of her forces there within a short period.[28] In 1630, Carl Banér was appointed Swedish legate in Stettin, succeeded in 1631 by Steno or Sten Svantesson Bielke,[nb 7][29] who in 1630 was the Swedish commander in Stralsund.[19]

From the Oder estuary bridgehead, the Swedish forces subsequently cleared the Duchy of Pomerania of imperial forces in 1631.[30] The Pomeranian towns of Gartz (Oder) and Greifenhagen (now Gryfino), both south of Stettin, were attacked on 4 and 5 January 1631.[30] The imperial occupation forces had established a defense in both towns since 4 and 7 June 1630.[31] With these taken, Sweden was able to advance further south into Brandenburg, and west into Western Pomerania and Mecklenburg.[30] The last imperial stronghold in Pomerania was Greifswald, which was besieged by Sweden since 12 June 1631.[2] When imperial commander Perusi was shot during a ride, the imperial garrison surrendered on 16 June.[2] Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden even returned from Brandenburg to supervise the siege, and upon his arrival received the university's homage for the liberation.[2]

Support for Sweden among the peasants did not fade even when they were mobilized and recruited for military construction works.[27] A different situation emerged in the towns, where burghers were often in conflict with the garrison.[2] While the Swedish king issued several decrees[nb 8] ruling and restricting the interaction of soldiers and burghers,[2] this did not prevent "turmoils against the undisciplined soldatesca" already in 1632.[32] The larger towns often refused to fulfill the demands of the Swedish military.[2]

| "Main fortress" (Hauptfestung) |

"Small fortress" (Kleine Festung) |

Major sconce (Schanze) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Soldiers in fall 1630 | Location | Soldiers in fall 1630 | Location | Soldiers in fall 1630 |

| Stettin (now Szczecin) |

4,230 | Anklam | 400 | Brandshagen | nd |

| Stralsund | 3,130 | Damm (now Szczecin-Dabie) |

280 | Damgarten (now part of Ribnitz-Damgarten) |

nd |

| Demmin | 830 | Peenemünde | nd | ||

| Greifswald | (taken in June 1631) | Neue Fähr (Rügen) | nd | ||

| Kolberg (now Kolobrzeg) |

1,000 | Tribsees | nd | ||

| Wolgast | 990 | Wieck (now part of Greifswald) |

1,050 | ||

| Wollin (town) (now Wolin) |

nd | ||||

| Data obtained from Langer (2003), pp. 397–398, citing the contemporary Swedish military administration. nd: No data cited. The number of units in the sconces varied. Langer (2003), p. 397. | |||||

Bridgehead for the Swedish intervention in the Holy Roman Empire

When Gustavus Adolphus landed in Pomerania, the German Protestant nobility met his intervention with distrust.[15][33] In April 1631, at a convention in Leipzig, they decided to set up a third front on their own,[28] and except for Magdeburg, who had allied with Sweden already on 1 August 1630,[15] did not side with Sweden.[33] In Swedish strategy, Magdeburg was to be the spark inflaming a "universal rebellion in Germany" - yet initially this strategy failed.[33]

In early 1631, Swedish forces advanced into Brandenburgian territory.[30] On 23 January 1631, Sweden concluded an alliance with France in Brandenburgian Bärwalde (now Mieszkowice) near Greiffenhagen.[30] Brandenburgian Frankfurt (Oder) and Landsberg (Warthe) (now Gorzow) were taken on 15 and 23 April, respectively.[30] Subsequently, Brandenburg was forced into treaties with Sweden on 14 May, 20 June and 10 September 1631.[30] While these obliged George William, Elector of Brandenburg to hand over control of the Brandenburgian military to Sweden, he refused to enter an alliance.[30]

Sweden was not able to support Magdeburg,[34] and in the summer of 1631, the town was taken and looted by Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly's forces.[28] When a fire destroyed what was left of the town, and 20,000 inhabitants were burned, the Protestants' scepsis turned into support for the Swedish king.[28] When Tilly attacked the Electorate of Saxony, the Saxon electors joined their forces with the Swedish army, and the combined forces decisively defeated Tilly in the Battle of Breitenfeld (1631).[34] This defeat of the combined imperial and Catholic League forces allowed Sweden to pursue deep into Central and Southern Germany.[35]

After Gustavus Adolphus' death

Gustavus Adolphus was killed in the Battle of Lützen on 6 November 1632.[36] George William, Elector of Brandenburg, joined the obsequies in Stettin on 31 May, and proposed joining the Alliance of Stettin if he would in turn participate in the Pomeranian succession.[24] Bogislaw XIV, Duke of Pomerania, the last living member of the House of Pomerania, had suffered a stroke already in April 1631.[24] Sweden neither approved nor rejected the Brandenburgian offer.[24] On 19 November 1634, a "regiment constitution"[nb 9] reformed the administration of the duchy of Pomerania.[24] The two governments in Wolgast and Stettin resulting from the partition of 1569 had already been merged on 18 March.[24] The new constitution reformed this government to consist of a proconsul, a president, and seven members.[24]

After Sweden had to acknowledge her first serious defeat in the Battle of Nördlingen (1634), Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor and several Protestant states concluded the Peace of Prague in May 1635.[36] Calvinist Brandenburg was reluctant to sign, since besides the announced annulment of the Edict of Restitution, toleration of Calvinism was not mentioned.[36] To get Brandenburg to sign up, Sweden and Ferdinand promised her the succession in the Duchy of Pomerania in return.[36]

Another consequence of the lost Battle of Nördlingen was that large parts of the Swedish army, including thousands of injured, retreated to Pomerania, followed by imperial forces who entered the duchy in 1636.[37] The riksråd considered to abandon all of Pomerania except for Stralsund.[37] Both the atrocities committed by the Swedish soldiers and the contributions paid by Pomerania for the military peaked during the following years.[37] Short of supplies, the Swedish as well as the imperial mercenaries forced their means of subsistence from the local population.[37] In 1637, a capitulation was issued that mentions "irruption" and "insolentia" by the military, and ruled out more drastic consequences for irregular behaviour of the soldiers.[37]

On 24 February 1637, the Pomeranian councillors decided that the Pomeranian constitution of 1634 should remain in effect in case of the duke's death, which was approved of by Sweden and rejected by Brandenburg.[38]

After Bogislaw XIV's death - Confrontation with Brandenburg

- For background information, see Brandenburg-Pomeranian conflict and Treaty of Grimnitz.

On 10 March 1637, Bogislaw XIV died without issue.[38] Swedish legate Sten Svantesson Bielke[nb 7] on 11 March advised the Pomeranian council to nevertheless adhere to the Alliance of Stettin, and to reject any Brandenburgian interference.[38] George William, Elector of Brandenburg, in turn mailed Christina of Sweden on 14 March to respect his succession in the Pomeranian duchy based on the treaties of Pyritz (1493) and Grimnitz (1529), on which the alliance did not have any impact.[38] Similar letters addressed Bielke, and Swedish field-marshal Carl Gustaf Wrangel.[38] The same day, a courier arrived in Stettin with the elector's seizure patent, who at once was incarcerated by Bielke and threatened with death by hanging.[38] The next day, the Brandenburgian elector admonished the Pomeranian nobility to behave as his subjects.[38]

On 19 March 1637, a delegation of Pomeranian nobles pledged that the elector suspend his claims until a Swedish-Brandenburgian agreement was reached.[38] The elector rejected,[38] and Bielke on 24 March rejected any negotiations with Brandenburg.[39] While Bielke clarified on 3 April, that he does not per se challenge the Brandenburgian claim, but rather Brandenburg's disregard of Swedish claims, Wrangel on 12 April definitely rejected any Brandenburgian claim and advised the Pomeranian nobility to remain loyal to Sweden.[39] George William reacted on 28 April, repeating his claims of 14 March and threatening with imperial intervention.[39] Ferdinand II issued a patent confirming the Brandenburgian succession, and George William issued another patent on 22 May.[6] The Pomeranians assembled a Landtag between 7 and 29 June, where Bielke and the nobility agreed on resisting the pending Brandenburgian take-over.[6]

In August 1637, an imperial army commanded by Matthias Gallas moved toward the Pomeranian frontier with Mecklenburg, and Swedish forces were concentrated on the Pomeranian side.[6] While Gallas withdrew in late October, imperial forces commanded by von Bredow crossed into Western Pomerania on 24/25 October taking Tribsees, Loitz, Wolgast and Demmin.[6] The nobles of the duchy's southern districts changed allegiance and rendered homage to the elector of Brandenburg on 25 November, and several nobles from the eastern districts Stolp and Schlawe met with the elector's ambassador in Danzig and obtained permission to resettle to East Prussia on 1 January 1638.[6] The same month, emperor Ferdinand II gave the duchy of Pomerania to Brandenburg as a fief, which was accepted by the nobility on 26 January.[40] The Pomeranian government resigned in March.[40]

On 3 April 1638, the Swedish riksråd debates the Pomeranian issue, and decides to take over the duchy.[40] On 2 May, Axel Lillje and Johann Lilljehök were appointed Swedish governors of Pomerania, occupied primarily with military tasks, and several other functionaries were appointed to administrate the duchy.[40] Johan Nicodemi Lilleström was appointed to draft a schedule for the final integration of Pomerania into the Swedish Empire.[40]

On 28 July 1638, Swedish field marshal Johan Banér from Farther Pomerania attacked the imperial forces in Western Pomerania.[40] The ensuing warfare devastated the duchy.[40] By the end of the year, Banér was appointed general governor of the whole duchy.[40] Though Brandenburg prepared a military re-capture throughout 1639–1641, she made no actual progress.[41] Neither did attempts of Sweden and the Pomeranian nobility to re-establish a civilian government succeed.[41] On 14 July 1641, Sweden and Brandenburg agreed on a truce.[42] Yet negotiations in February 1642 and April 1643 did not result in a settlement.[42]

Between 1 and 7 September 1643, imperial forces commanded by von Krockow invaded the Duchy of Pomerania and took western Farther Pomerania.[42] Swedish forces commanded by Hans Christoff von Königsmarck attacked Krockow on 1 October, the battles lasted until 12 November when Krockow retreated pursued by Königsmarck's forces.[43]

Aftermath

When peace talks started in Osnabrück to end the Thirty Years' War, a Pomeranian delegation was present in early 1644 and from October 1645 to August 1647.[43] Stralsund had sent her own delegates, and the rest of the duchy was represented by von Eickstedt and Runge, accredited by both Sweden and Brandenburg.[43] On 3 August, George William of Brandenburg's delegation started to negotiate a partition of the duchy with Sweden.[43] While the Pomeranian nobility in October rejected a partition and urged Brandenburg to look for alternatives, the partition was made definite on 28 January 1647 in Osnabrück, signed as Peace of Westphalia on 24 October 1648: Western Pomerania was to remain with Sweden, while Farther Pomerania was to become a fief of Brandenburg.[44] Swedish field-marshal Carl Gustaf Wrangel was appointed general governor of Pomerania in 1648.[44] After the peace treaty, Sweden demobilized her forces in Pomerania, keeping between 2,000 and 4,000 troops.[45]

Swedish-Brandenburgian negotiations about the definite frontier started in early 1650,[46] resulting in another Treaty of Stettin which defined the exact border on 4 May 1653.[7] Bogislaw XIV was finally buried in Stettin on 25 May 1654.[47]

See also

Notes

- In the 17th century, the Julian calendar was used in the region, which then was ten days late compared to the Gregorian calendar:

Swedish invasion: 10 July - Julian, 20 July - Gregorian;

Treaty: 25 August - Julian, 4 September - Gregorian. - The Swedish military reform of 1623 divided the Lands of Sweden into nine military recruitment districts, each of which had to provide 3,600 soldiers. Able peasants between 15 and 60 years of age were put into selection groups of ten people each, and one of each group was recruited. On the one hand, this system reduced Sweden's war costs - on the other hand, it led to rebellions, desertions, and emigration from sparsely populated districts. Kroll (2003), pp. 143–144. See also: Swedish allotment system.

- Basically referring to the principle of cuius regio, eius religio as determined in the Peace of Augsburg (1555)

- "Pommersche Defensivverfassung"

- "Quartierordinnance"

- "Kriegs-Regiment"

- Sten Svantesson Bielke (1598-1638). Not to be confused with Sten Bielke the Younger (1624-1684, Swedish rigsrådet). Backhaus (1969), p. 19. Droste (2006), p. 423

- Artikelbriefe

- Regimentsverfassung

Sources

References

- Sturdy (2002), p. 59

- Langer (2003), p. 406

- Heitz (1995), p. 220

- Parker (1997), pp. 120ff

- Heitz (1995), pp. 223–229

- Heitz (1995), p. 225

- Heitz (1995), p. 232

- Langer (2003), p. 402

- Heckel (1983), p. 143

- Press (1991), p. 213

- Olesen (2003), p. 390

- Lockhart (2007), p. 168

- Kohler (1990), p. 37

- Theologische Realenzyklopädie I (1993), p. 172

- Ringmar (1996), p. 5

- Schmidt (2006), p. 49

- Oakley (1992), p. 69

- Kroll (2000), p. 143

- Olesen (2003), p. 394

- Schmidt (2006), p. 50

- Porshnev (1995), p. 180

- Oakley (1992), p. 70

- Nordisk familjebok 21, p. 1327

- Heitz (1995), p. 221

- Sturdy (2002), pp. 59–60

- Porshnev (1995), p. 176

- Porshnev (1995), p. 179

- Schmidt (2006), p. 51

- Backhaus (1969), p. 19

- Theologische Realenzyklopädie I (1993), p. 175

- Heitz (1995), p. 219

- Langer (2003), p. 407

- Lorenzen (2006), p. 67

- Schmidt (2006), p. 52

- Porshnev (1995), p. 118

- Clark (2006), p. 25

- Langer (2003), p. 408

- Heitz (1995), p. 223

- Heitz (1995), p. 224

- Heitz (1995), p. 226

- Heitz (1995), pp. 227–228

- Heitz (1995), p. 228

- Heitz (1995), p. 229

- Heitz (1995), p. 230

- Langer (2003), p. 398

- Heitz (1995), p. 231

- Heitz (1995), p. 233

Bibliography

- Backhaus, Helmut (1969). Reichsterritorium und schwedische Provinz: Vorpommern unter Karls XI. Vormündern 1660-1672 (in German). Vandenhoeck u. Ruprecht.

- Clark, Christopher M (2006). Iron kingdom: the rise and downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02385-4. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- Droste, Heiko (2006). Im Dienst der Krone: Schwedische Diplomaten im 17. Jahrhundert (in German). Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. ISBN 3-8258-9256-5.

- Heitz, Gerhard; Rischer, Henning (1995). Geschichte in Daten. Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (in German). Münster-Berlin: Koehler&Amelang. ISBN 3-7338-0195-4.

- Heckel, Martin (1983). Deutschland im konfessionellen Zeitalter (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 3-525-33483-4.

- Kohler, Alfred (1990). Das Reich im Kampf um die Hegemonie in Europa 1521-1648 (in German). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. ISBN 3-486-55461-1.

- Krause, Gerhard; Balz, Horst Robert (1993). Müller, Gerhard (ed.). Theologische Realenzyklopädie I (in German). Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-013898-0.

- Kroll, Stefan; Krüger, Kersten (2000). Militär und ländliche Gesellschaft in der frühen Neuzeit (in German). Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. ISBN 3-8258-4758-6.

- Langer, Herbert (2003). "Die Anfänge des Garnisionswesens in Pommern". In Asmus, Ivo; Droste, Heiko; Olesen, Jens E. (eds.). Gemeinsame Bekannte: Schweden und Deutschland in der Frühen Neuzeit (in German). Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. ISBN 3-8258-7150-9.

- Lockhart, Paul Douglas (2007). Denmark, 1513-1660: the rise and decline of a Renaissance monarchy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-927121-6. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- Lorenzen, Jan N. (2006). Die grossen Schlachten: Mythen, Menschen, Schicksale. Campus Verlag. ISBN 3-593-38122-2. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- Meijer, Bernhard, ed. (1915). Nordisk familjebok: konversationslexikon och realencyklopedi (21 ed.). Nordisk familjeboks förlags aktiebolag.

- Oakley, Stewart P. (1992). War and peace in the Baltic, 1560-1790. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-02472-2. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- Olesen, Jens E (2003). "Christian IV og dansk Pommernpolitik". In Asmus, Ivo; Droste, Heiko; Olesen, Jens E. (eds.). Gemeinsame Bekannte: Schweden und Deutschland in der Frühen Neuzeit (in Danish). Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. ISBN 3-8258-7150-9.

- Parker, Geoffrey; Adams, Simon (1997). The Thirty Years' War (2 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12883-8. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- Porshnev, Boris Fedorovich; Dukes, Paul (1995). Muscovy and Sweden in the Thirty Years' War, 1630-1635. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45139-6. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- Press, Volker (1991). Kriege und Krisen: Deutschland 1600-1715 (in German). C.H.Beck. ISBN 3-406-30817-1.

- Ringmar, Erik (1996). Identity, interest and action: A cultural explanation of Sweden's intervention in the Thirty Years War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56314-3.

- Schmidt, Georg (2006). Der Dreissigjährige Krieg (in German) (7 ed.). C.H.Beck. ISBN 3-406-49034-4.

- Sturdy, David J. (2002). Fractured Europe, 1600-1721. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-20513-6.