Treaty of Oliva

The Treaty or Peace of Oliva of 23 April (OS)/3 May (NS) 1660[1] (Polish: Pokój Oliwski, Swedish: Freden i Oliva, German: Vertrag von Oliva) was one of the peace treaties ending the Second Northern War (1655-1660).[2] The Treaty of Oliva, the Treaty of Copenhagen in the same year, and the Treaty of Cardis in the following year marked the high point of the Swedish Empire.[3][4]

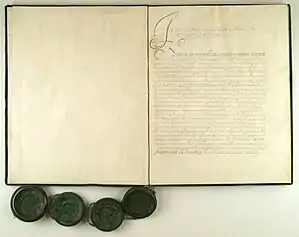

Treaty of Oliwa, first page of the document | |

| Type | peace treaty |

|---|---|

| Drafted | 1659–1660 |

| Signed | 23 April (O.S.)/3 May (N.S.) 1660 |

| Location | Oliva, Poland |

| Parties | |

At Oliva (Oliwa), Poland, peace was made between Sweden, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Habsburgs and Brandenburg-Prussia. Sweden was accepted as sovereign in Swedish Livonia, Brandenburg was accepted as sovereign in Ducal Prussia, and John II Casimir Vasa withdrew his claims to the Swedish throne, though he was to retain the title of a hereditary Swedish king for life.[2] All occupied territories were restored to their pre-war sovereigns.[2] Catholics in Livonia and Prussia were granted religious freedom.[1][2][5][6]

The signatories were the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, Elector Frederick William I of Brandenburg and King John II Casimir Vasa of Poland. Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie, head of the Swedish delegation and the minor regency, signed on behalf of his nephew, King Charles XI of Sweden, who was still a minor at the time.[7]

Negotiations

During the Second Northern War, Poland-Lithuania and Sweden had been engaged in a ravaging war since 1655 and both wanted peace, in order to attend to their remaining enemies, Russia and Denmark respectively. In addition, the politically ambitious Polish queen Marie Louise Gonzaga, who had great influence over both the Polish king and Polish parliament (the Sejm), wanted a peace with Sweden because she wanted a son of her close relative, the French Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé, to be elected as successor to the Polish throne.[8] This could only be achieved with the consent of France and its ally Sweden.[9]

On the other hand, the Danish and Dutch envoys, as well as those of the Holy Roman Empire and Brandenburg, did what they could to derail the proceedings.[8] Their goal was assisted by the drawn-out formalities which always took place at negotiations of this age. Several months elapsed before the actual peace negotiations could begin, on 7 January 1660 (old style). Even then, so many hostile words were written in the documents being exchanged by the two parties that the head negotiator, French ambassador Antoine de Lombres, found himself having to expurgate long sections which otherwise would have caused offense.

A Polish contingent headed by the archbishop of Gniezno wanted the war to continue in order to expel the exhausted Swedish forces in Livonia. The Danish delegates demanded of Poland conclude a treaty together with Denmark; the Poles did however not want to tie themselves to the outcome of the poor Danish fortunes of war against Sweden. Austria, which wished to drive Sweden out of Germany through continued warfare, promised Poland reinforcements, but Austrian intentions were treated with suspicion and the Polish Senate demurred. Even Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg offered assistance to Poland to continue the war, with the hope of conquering Swedish Pomerania. [10]

France, which in practice was governed by Cardinal Mazarin, wanted a continued Swedish presence in Germany to counterbalance Austria and Spain, which were traditional enemies of France. France also feared that a continued war would increase Austria's influence in Germany and Poland. The Austrian and Brandenburgian intrusion into Swedish Pomerania was considered a breach of the Peace of Westphalia, which France was under the obligation to prosecute. France therefore threatened to contribute an army of 30,000 soldiers to the Swedish cause unless a treaty between Sweden and Brandenburg was concluded before February 1660.

.jpg.webp)

Negotiations had begun in Toruń (Thorn) in autumn of 1659; the Polish delegation later moved to Gdansk while the Swedish delegation made the Baltic town of Sopot (Zoppot) its base. When news of the death of king Charles X of Sweden arrived Poland, Austria, and Brandenburg began increasing their demands. But a new French threat of assistance to Sweden finally made the Polish side give in. The treaty was signed in the monastery of Oliwa on 23 April 1660.[11]

Terms

In the treaty John II Casimir renounced his claims to the Swedish crown, which his father Sigismund III Vasa had lost in 1599. Poland also formally ceded to Sweden Livonia and the city of Riga, which had been under Swedish control since the 1620s. The treaty settled conflicts between Sweden and Poland left standing since the War against Sigismund (1598-1599), the Polish-Swedish War (1600-1629), and the Northern Wars (1655-1660).

The Hohenzollern dynasty of Brandenburg was also confirmed as independent and sovereign over the Duchy of Prussia; previously they had held the territory as a fief of Poland. In case of an end to the Hohenzollern dynasty in Prussia, the territory was to revert to the Polish crown. The treaty was achieved by Brandenburg's diplomat, Christoph Caspar von Blumenthal, on the first diplomatic mission of his career.

See also

- Swedish Livonia

- Polish Livonia

- List of Swedish wars

- List of treaties

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treaty of Oliwa. |

References

- Evans (2008), p.55

- Frost (2000), p.183

- "Freden i København, 27. maj 1660". danmarkshistorien.dk. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- Nina Ringbom. "Freden i Kardis 1661". Historiesajten. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- "Friede von Oliva". Monarchieliga. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- Nina Ringbom. "Freden i Oliva 1660". Historiesajten. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- Bély (2000), p.511

- Starbäck (1885/86), p.363

- Georges Mongrédien. "Louis II de Bourbon, prince de Condé". britannica.com. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- Stephan Skalweit. "Frederick William, elector of Brandenburg". britannica.com. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- "Oliwa Cathedral". whattodoingdansk.com/. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

Bibliography

- Bély, Lucien; Isabelle Richefort (2000). Lucien Bély (ed.). L'Europe des traités de Westphalie: esprit de la diplomatie et diplomatie de l'esprit. Presses universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-049964-3.

- Evans, Malcolm (2008). Religious Liberty and International Law in Europe. Cambridge Studies in International and Comparative Law. 6. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-04761-7.

- Frost, Robert I (2000). The Northern Wars. War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe 1558-1721. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-06429-4.

- Starbäck, Carl Georg; Bäckström, Per Olof (1885–1886). Berättelser ur svenska historien. 6.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) (Stockholm: F. & G. Beijers Förlag)