Pomerelia

Pomerelia (German: Pomerellen, Pommerellen), also referred to as Eastern Pomerania or Gdańsk Pomerania (Polish: Pomorze Wschodnie, Pomorze Gdańskie), is a historical sub-region of Pomerania, in northern Poland. Pomerelia lay on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea, west of the Vistula river and east of the Łeba river. Its largest and most important city is Gdańsk. Since 1999 the region has formed the core of the Pomeranian Voivodeship. Gdańsk Pomerania is traditionally divided into Kashubia and Kociewie, which are inhabited by ethnic Kashubians and speakers of the Kashubian language.

Early history

In its early history, the territory which later became known as Pomerelia was the site of the Pomeranian Culture (also called the Pomerelian face urn culture, 650-150 BC),[1] the Oksywie culture (150 BC-AD 1, associated with parts of the Rugii and Lemovii),[2] and the Wielbark Culture (AD 1-450, associated with Veneti, Goths, Rugii, Gepids).[3] In the mid-6th century Jordanes mentioned the Vistula estuary as the home of the Vidivarii.[4] Pomerelia was settled by West Slavic and Lechitic tribes[5] in the 7th and 8th centuries.[6]

As part of Poland

In the tenth century, Pomerelia was already settled by West-Slavic Pomeranians. The area was conquered and incorporated into early medieval Poland either by Duke Mieszko I – the first historical Polish ruler - in the second half of the tenth century[7] or even earlier, by his father, in the 940s or 950s[8] – the date of incorporation is unknown.[9] Mieszko founded Gdańsk to control the mouth of the Vistula between 970 and 980,.[10] According to Józef Spors, despite some cultural differences, the inhabitants of the whole of Pomerania had very close ties with residents of other Piast provinces,[11] from which Pomerelia was separated by large stretches of woodlands and swamps.[9]

The Piasts introduced Christianity to pagan Pomerelia, though it is disputed to what extent the conversion materialized.[12] In the eleventh century the region had loosened its close connections with the kingdom of Poland and subsequently for some years formed an independent duchy.[13] Most scholars suggest that Pomerelia was still part of Poland during the reign of king Bolesław I of Poland and his son Mieszko II Lambert. However, there are also different opinions e.g. Peter Oliver Loew suggests the Slavs in Pomerelia severed their ties with the Piasts and reverted the Piasts' introduction of Christianity already in the first years of the 11th century.[14] The exact date of separation is unknown, however. It was suggested that the inhabitants of Pomerelia participated in the Pagan reaction in Poland, actively supported Miecław who intended to detach Masovia from the power of the rulers of Poland, but after the defeat of Miecław in 1047 accepted the rule of duke Casimir I the Restorer and that the province remained a part of Poland till the 1060s, when Pomerelian troops took part in the expedition of the Polish king Bolesław II the Generous against Bohemia in 1061 or 1068. Duke Bolesław suffered a defeat during the siege of Hradec and had to retreat to Poland. Soon after Pomerelia separated from his realm.[15] A campaign by Piast duke Władysław I Herman to conquer Pomerelia in 1090–91 was unsuccessful, but resulted in the burning of many Pomerelian forts during the retreat.[9]

In 1116, direct control over Pomerelia was reestablished by Bolesław III Wrymouth of Poland,[16] who by 1122 had also conquered the central and western parts of Pomerania.[17] While the latter regions (forming the Duchy of Pomerania) regained independence quickly, Pomerelia remained within the Polish realm. It was administered by governors of a local dynasty, the Samborides, and subordinated to the bishopric of Włocławek.[9] In 1138, following the death of Bolesław III, Poland was fragmented into several semi-independent principalities. The principes in Pomerelia gradually gained more local power, evolving into semi-independent entities, much like other fragmented Polish territories, with the difference that the other parts of the realm were governed by Piast descendants of Bolesław III. The Christian centre became Oliva Abbey near Gdańsk.

Two Samborides administering Pomerelia in the 12th century are known by name: Sobieslaw I and his son, Sambor I.[9]

Danish conquest and independence

In 1210, king Valdemar II of Denmark invaded Pomerelia, whose princeps Mestwin I became his vassal.[18] The Danish suzerainty did not last long, however. Mestwin had already gained more independence from Poland and expanded southward, and his son Swietopelk II, who succeeded him in 1217,[19] gained full independence in 1227.[13]

Duchy of Pomerelia

After Mestwin I's death, Pomerelia was internally divided among his sons Swietopelk II, Wartislaw, Sambor II and Ratibor.[20] Swietopelk II, who took his seat in Gdańsk, assumed a leading position over his brothers: Sambor II, who received the castellany of Lubieszewo (the center later moved to Tczew), and Ratibor, who received the Białogard area, were initially under his tutelage.[20] The fourth brother, Wartislaw, took his seat in Świecie, thus controlling the second important area besides Gdańsk.[20] Wartislaw died before 27 December 1229, his share was to be given to Oliva Abbey by his brothers.[21] The remaining brothers engaged in a civil war: Sambor II and Ratibor allied with the Teutonic Order[21][22] and the Duke of Kuyavia[21] against Swietopelk, who in turn allied with the Old Prussians,[22] took Ratibor prisoner and temporarily assumed control over the latter's share.[21] The revolt of the Old Prussians against the Teutonic Order in 1242 took place in the context of these alliances.[22] Peace was restored only in the Treaty of Christburg (Dzierzgoń) in 1249, mediated by the later pope Urban IV, then papal legate and archidiacone of Lüttich (Liege).[22]

In the west, the Pomerelian dukes' claim to the lands of Schlawe (Sławno) and Stolp (Słupsk), where the last Ratiboride duke Ratibor II had died after 1223, was challenged by the Griffin dukes of Pomerania, Barnim I and Wartislaw III.[23] In this conflict, Swietopelk II initially won the upper hand, but could not force a final decision.[23]

Swietopelk II, who styled himself dux. since 1227, chartered the town of Gdańsk with Lübeck law and invited the Dominican Order.[19] His conflicts with the Teutonic Order, who had become his eastern neighbor in 1230, were settled in 1253 by exempting the order from the Vistula dues.[19] With Swietopelk II's death in 1266, the rule of his realm passed to his sons Wartislaw and Mestwin II.[19] These brothers initiated another civil war, with Mestwin II allying with and pledging allegiance to the Brandenburg margraves (Treaty of Arnswalde/Choszczno 1269).[19] The margraves, who in the 1269 treaty also gained the land of Białogard, were also supposed to help Mestwin II securing the lands of Schlawe (Sławno) and Stolp (Słupsk), which after Swietopelk II's death were in part taken over by Barnim III.[24] With the margraves' aid, Mestwin II succeeded in expelling Wartislaw from Gdansk in 1270/71.[19] The lands of Schlawe/Slawno, however, were taken over by Mestwin II's nephew Wizlaw II, prince of Rügen in 1269/70, who founded the town of Rügenwalde (now Darlowo) near the fort of Dirlow.[24]

In 1273 Mestwin found himself in open conflict against the margraves who refused to remove their troops from Gdańsk, Mestwin's possession, which he had been forced to temporarily lease to them during his struggles against Wartisław and Sambor. Since the lease had now expired, through this action, the Margrave Conrad broke the Treaty of Arnswalde/Choszczno and subsequent agreements. His aim was to capture as much of Mestwin's Pomerelia as possible. Mestwin, unable to dislodge the Brandenburgian troops himself called in the aid of Bolesław the Pious, whose troops took the city with a direct attack. The war against Brandenburg ended in 1273 with a treaty [25] (possibly signed at Drawno Bridge), in which Brandenburg returned Gdańsk to Mestwin while he paid feudal homage to the margraves for the lands of Schlawe (Sławno) and Stolp (Słupsk).[26]

On February 15, 1282, High Duke of Poland and Wielkopolska Przemysł II and the Duke of Pomerelia Mestwin II, signed the Treaty of Kępno which transferred the suzerainty over Pomerelia to Przemysł.[27] As a result of the treaty the period of Pomerelian independence ended and the region was again part of Poland. Przemysł adopted the title dux Polonie et Pomeranie (Duke of Poland and Pomerania).[28] Mestwin, per the agreement, retained de facto control over the province until his death in 1294, at which time Przemysł, who was already the de jure ruler of the territory, took it under his direct rule.[27]

Rulers

- Świętobor, Duke (11th–12th century)

- Swietopelk I, Duke (1109/13–1121)

- Sobieslaw I, Duke (1150s–1177/79)

- Sambor I, Duke (1177/79–1205)

- Mestwin I, Duke (1205–1219/20)

- Swietopelk II, Duke (1215–1266)

- Mestwin II, Duke (1273–1294)

- Przemysł II, Duke (1294–1296)

Polish rule

After the death of Mestwin II of Pomerania in 1294, his co-ruler Przemysł II of Poland, according to the Treaty of Kępno, took control over Pomerelia. He was crowned as king of Poland in 1295, but ruled directly only over Pomerelia and Greater Poland, while the rest of the country (Silesia, Lesser Poland, Masovia) was ruled by other Piasts. However, Przemysł was murdered soon afterwards and succeeded by Władysław I the Elbow-high. Władysław, sold his rights to the Duchy of Kraków to King Wenceslaus II of Bohemia in 1297 and accepted him as his suzerain in 1299. However, he lost control of Greater Poland and Pomerelia in 1300 after a nobility revolt.[29] These were captured by Wenceslaus who now, after gaining most of the Polish lands, was crowned in Gniezno as king of Poland by archbishop Jakub Świnka[30] Upon the deaths of Wenceslaus and his successor Wenceslaus III and with them the extinction of the Přemyslid dynasty, Pomerelia was recaptured by Władysław I the Elbow-high in 1306.

Teutonic Order state and Poland-Lithuania

During Władysław's rule, the Margraviate of Brandenburg staked its claim on the territory in 1308, leading Władysław I the Elbow-high to request assistance from the Teutonic Knights, who evicted the Brandenburgers but took the area for themselves, annexing and incorporating it into the Teutonic Order state in 1309 (Teutonic takeover of Danzig (Gdańsk) and Treaty of Soldin/Myślibórz). At the same time, Słupsk and Sławno became part of the Duchy of Pomerania. This event caused a long-lasting dispute between Poland and the Teutonic Order over the control of Gdańsk Pomerania. It resulted in a series of Polish–Teutonic Wars throughout the 14th and 15th centuries.

Pomerelia was made part of Polish Royal Prussia as the Pomeranian Voivodeship in 1466. Lauenburg and Bütow Land was a Polish fief ruled by Pomeranian dukes. In early modern times Gdańsk was the biggest city of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and most of its exports (especially grain) were made through the port. Gdańsk and Żuławy Wiślane were German/Dutch Lutheran or Reformed, while most of the region remained Polish/Kashubian Catholic. In the 17th century Pomerelia was attacked and destroyed by a Swedish army.

Pomerelia as the western part of Prussia and Polish Corridor

As part of Royal Prussia, Pomerelia was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia during the 18th century Partitions of Poland, becoming part of the new Province of West Prussia. After World War I (1914–1918), the Treaty of Versailles transferred most of the region from Weimar Germany to the new Second Polish Republic, forming the Pomeranian Voivodeship (Greater Pomerania as of 1938) in the so-called Polish Corridor. Gdańsk with Żuławy became the Free City of Danzig. In 1939 Pomerelia was occupied and illegally annexed by Nazi Germany.

In 1945 the whole region, including the former Free City of Danzig, was assigned to Poland according to the Potsdame Agreement. Local Germans were expelled from their home for new Polish settlers to take their place. Some Germans fled earlier as the Red Army advanced.

Historic Pomerelia nowaday roughly corresponds to the Gdańsk Voivodeship, as well as the dioceses of Gdańsk and Pelplin.

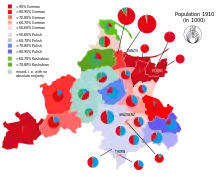

Historical population

Legend for the districts:

During the Early Middle Ages Pomerelia (the name comes from Proto-Slavic "po more", which means "land at the sea") was inhabited by West Slavic, Lechitic tribes. Some Scandinavian trading posts were also present in major gords and towns. Starting in the High Middle Ages, many German and Dutch settlers came during the Ostsiedlung. Following the occupation of the area by the Teutonic Order, the main city of the region became dominated by German-speaking settlers (in year 1770, Germans were 58% of the urban population[36]), while in rural areas and smaller towns, the speakers of Kashubian and Greater Polish (i.e. Kociewiacy, and Borowiacy) predominated. The Teutonic Order developed the land in amelioration projects, dyking of the founding of German-settled Estates and villages.[37]

As the result of the Thirteen Years' War of 1454-1466, Pomerelia became part of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland again, within Royal Prussia (the area of which was not identical with the area of Pomerelia, as the province of Royal Prussia included also other regions, such as Chełmno Land, Pomesania and Warmia). After the Partitions of Poland in 1772-1795, historical Pomerelia became part of the new province of West Prussia within the Kingdom of Prussia. Temporarily, during the Napoleonic Wars until 1815, Gdańsk became a Free City, while southern portions of West Prussia with Toruń became parts of the Duchy of Warsaw. Perhaps the earliest census figures (from years 1817 and 1819) about the ethnic or national composition of the region come from Prussian data published in 1823. At that time, entire West Prussia (of which historical Pomerelia was part) had 630,077 inhabitants – 327,300 ethnic Poles (52%), 290,000 Germans (46%) and 12,700 Jews (2%).[38] In this data Kashubians are included with Poles, while Mennonites (numbering 2% of West Prussia's population) are included with Germans.

| Ethnic or national group | Population | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | |

| Poles (Polen) | 327,300 | 52% |

| Germans (Deutsche) | 290,000 | 46% |

| Jews (Juden) | 12,700 | 2% |

| Total | 630,077 | 100% |

Another German author, Karl Andree, in his book "Polen: in geographischer, geschichtlicher und culturhistorischer Hinsicht" (Leipzig 1831), gives the total population of West Prussia as 700,000 inhabitants – including 50% Poles (350,000), 47% Germans (330,000) and 3% Jews (20,000).[39]

There are also estimates of the religious structure (number of temples) of the pre-1772 Pomerelian Voivodeship of Poland. Around year 1772 that voivodeship had 221 (66,6%) Roman Catholic, 79 (23,8%) Lutheran, 23 (6,9%) Jewish, six (1,8%) Mennonite, two (0,6%) Czech Brethren and one (0,3%) Calvinist churches:

| Voivodeship | Roman Catholic | Lutheran | Calvinist | Czech Brethren | Mennonite | Jewish |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pomerelia | 221 | 79 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 23 |

| Lębork-Bytów | 15 | 23 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Malbork | 62 | 47 | 1 | - | 9 | - |

| Warmia | 124 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Chełmno | 151 | 11 | - | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| TOTAL Royal Prussia | 573 | 160 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 32 |

See also

References

- Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.23, ISBN 83-906184-8-6

- J. B. Rives on Tacitus, Germania, Oxford University Press, 1999, p.311, ISBN 0-19-815050-4

- Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.25, ISBN 83-906184-8-6

- Andrew H. Merrills, History and Geography in Late Antiquity, Cambridge University Press, 2005, p.325, ISBN 0-521-84601-3

- Gerhard Köbler, Historisches Lexikon der Deutschen Länder: die deutschen Territorien vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, 7th edition, C.H.Beck, 2007, p.532, ISBN 3-406-54986-1

- Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.29, ISBN 83-906184-8-6

- Jerzy Strzelczyk [in:] The New Cambridge Medieval History, Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 523 ISBN 0-521-36447-7 Google Books

- J. Spors (in:) J. Borzyszkowski (red.) Pomorze w dziejach Polski, Nr 19 - Pomorze Gdańskie, Gdańsk 1991, p. 68

- Loew, Peter Oliver: Danzig. Biographie einer Stadt, Munich 2011, p. 32.

- J. Spors (in:) J. Borzyszkowski (red.) Pomorze w dziejach Polski, Nr 19 - Pomorze Gdańskie, Gdańsk 1991, p. 69–70

- J. Spors (in:) J. Borzyszkowski (red.) Pomorze w dziejach Polski, Nr 19 - Pomorze Gdańskie, Gdańsk 1991, p. 67

- Machilek, Franz: Strukturen und Repräsentanten der Kirche Polens im Mittelalter, in Dietmar Popp, Robert Suckale (eds.): Die Jagiellonen. Kunst und Kultur einer europäischen Dynastie an der Wende zur Neuzeit (Wissenschaftliche Beibände zum Anzeiger des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, Bd. 21), Nürnberg 2002, pp. 109–122; 109.

- James Minahan, One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, p. 375, ISBN 0-313-30984-1

- Loew, Peter Oliver: Danzig. Biographie einer Stadt, Munich 2011, p. 32; while James Minahan, One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, p. 375 generally speaks of the 11th century.

- J. Spors (in:) J. Borzyszkowski (red.) Pomorze w dziejach Polski, Nr 19 - Pomorze Gdańskie, Gdańsk 1991, p. 73, B. Śliwiński (red.) Wielka Historia Polski, t. I do 1320, Kraków 1997, p. 89-90. Both these authors connect the unsuccessful campaign against he Czechs with the loss of Pomerelia.

- Andrzej Chwalba (2000). Wydawnictwo Literackie (ed.). Kalendarium Historii Polski (in Polish). Kraków. p. 45. ISBN 83-08-03136-6.

- Andrzej Chwalba (2000). Wydawnictwo Literackie (ed.). Kalendarium Historii Polski (in Polish). Kraków. pp. 45–56. ISBN 83-08-03136-6.

- Andrzej Chwalba (2000). Wydawnictwo Literackie (ed.). Kalendarium Historii Polski (in Polish). Kraków. p. 58. ISBN 83-08-03136-6.

- Loew, Peter Oliver: Danzig. Biographie einer Stadt, Munich 2011, p. 33.

- Lingenberg, Heinz: Die Anfänge des Klosters Oliva und die Entstehung der deutschen Stadt Danzig. Die frühe Geschichte der beiden Gemeinwesen bis 1308/10 (Kieler historische Studien, Bd. 30), Stuttgart 1982, p. 191.

- Hirsch, Theodor et al. (eds.): Scriptores rerum Prussicarum, vol. 1, Leipzig 1861, pp. 67, 686-687.

- Wichert, Sven: Das Zisterzienskloster Doberan im Mittelalter (Studien zur Geschichte, Kunst und Kultur der Zisterzienser, vol. 9), Berlin 2000, p. 208

- Schmidt, Roderich: Das historische Pommern. Personen, Orte, Ereignisse, Köln/Weimar 2007, pp. 141-142.

- Schmidt, Roderich: Das historische Pommern. Personen, Orte, Ereignisse, Köln/Weimar 2007, p. 143.

- Full text of the treaty of Drage Bridge (1273) (in Latin) in Morin FH (1838): Codex diplomaticus Brandenburgensis I, p. 121.

- B. Śliwiński (red.) Wielka Historia Polski, t. I do 1320, Kraków 1997, p. 205

- Muzeum Historii Polski (2010). "Układ w Kępnie między Przemysłem II a Mszczujem II Pomorskim". Muzhp.pl. Archived from the original on 2012-03-24. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- Aneta Kwiatkowska (March 12, 2008). "O przesławnych książętach pomorskich". dziedzictwo.polska.pl. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- Andrzej Chwalba (2000). Wydawnictwo Literackie (ed.). Kalendarium Historii Polski (in Polish). Kraków. pp. 70–71. ISBN 83-08-03136-6.

- Andrzej Chwalba (2000). Wydawnictwo Literackie (ed.). Kalendarium Historii Polski (in Polish). Kraków. p. 71. ISBN 83-08-03136-6.

- Andrzej Chwalba - Historia Polski 1795-1918 pages 461-463

- Anna Cienciala Lecture Notes 11 The Rebirth of Poland, The University of Kansas

- Poloźenie mniejszości niemieckej w Polsce, 1918-1938 1969 Stanisław Kazimierz Potocki Wydawn. Morskie, page 30

- Ruch polski na Śląsku Opolskim w latach 1922-1939 - page 15 Marek Masnyk - 1989

- Dzieje robotników przemysłowych w Polsce pod zaborami Elżbieta Kaczyńska Państwowe Wydawn. Naukowe, 1970, page 75To show lower number of Poles, settled German soldiers were automatically included. The census of 1910 was most likely falsified

- Szady, Bogumił (2010). Geography of Religious and Denominational Structures in the Crown of the Polish Kingdom in the Second Half of the 18th Century (PDF). Wydawnictwo KUL. pp. 164–165.

- Kazimierz Śmigiel (1992). Die statistischen Erhebungen über die deutschen Katholiken in den Bistümern Polens, 1928 und 1936. J.G. Herder-Institut. p. 117.

- Hassel, Georg (1823). Statistischer Umriß der sämmtlichen europäischen und der vornehmsten außereuropäischen Staaten, in Hinsicht ihrer Entwickelung, Größe, Volksmenge, Finanz- und Militärverfassung, tabellarisch dargestellt; Erster Heft: Welcher die beiden großen Mächte Österreich und Preußen und den Deutschen Staatenbund darstellt. Verlag des Geographischen Instituts Weimar. p. 42.

- Andree, Karl (1831). Polen: in geographischer, geschichtlicher und culturhistorischer Hinsicht. Verlag von Ludwig Schumann. p. 212.

External links

![]() Media related to Pomeralia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pomeralia at Wikimedia Commons

- Map of Pomerelia (within a map of the Holy Roman Empire, 1138–1254)