Tian Shan

The Tian Shan,[lower-alpha 1] also known as the Tengri Tagh[1] or Tengir-Too,[2] (Old Turkic: 𐰴𐰣 𐱅𐰭𐰼𐰃 , Uyghur: تەڭرىتاغ , Chinese: 天山) meaning the Mountains of Heaven or the Heavenly Mountain, is a large system of mountain ranges located in Central Asia. The highest peak in the Tian Shan is Jengish Chokusu, at 7,439 metres (24,406 ft) high. Its lowest point is the Turpan Depression, which is 154 m (505 ft) below sea level.[3]

| Tian Shan | |

|---|---|

| 天山 | |

The Tian Shan range on the border between China and Kyrgyzstan with Khan Tengri (7,010 m) visible at center | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Jengish Chokusu |

| Elevation | 7,439 m (24,406 ft) |

| Coordinates | 42°02′06″N 80°07′32″E |

| Geography | |

| Countries | |

| Range coordinates | 42°N 80°E |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Mesozoic and Cenozoic |

| Official name | Xinjiang Tianshan |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | vii, ix |

| Designated | 2013 (37th session) |

| Reference no. | 1414 |

| State Party | China |

| Region | Asia |

| Official name | Western Tien-Shan |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | x |

| Designated | 2016 (40th session) |

| Reference no. | 1490 |

| State Party | Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan |

| Region | Asia |

One of the earliest historical references to these mountains may be related to the Xiongnu word Qilian (simplified Chinese: 祁连; traditional Chinese: 祁連; pinyin: Qí lián) – according to Tang commentator Yan Shigu, Qilian is the Xiongnu word for sky or heaven.[4] Sima Qian in the Records of the Grand Historian mentioned Qilian in relation to the homeland of the Yuezhi and the term is believed to refer to the Tian Shan rather than the Qilian Mountains 1,500 kilometres (930 mi) further east now known by this name.[5][6] The Tannu-Ola mountains in Tuva has the same meaning in its name ("heaven/celestial mountains" or "god/spirit mountains"). The name in Chinese, Tian Shan, is most likely a direct translation of the traditional Kyrgyz name for the mountains, Teñir Too.[7] The Tian Shan is sacred in Tengrism, and its second-highest peak is known as Khan Tengri which may be translated as "Lord of the Spirits".[8]

Geography

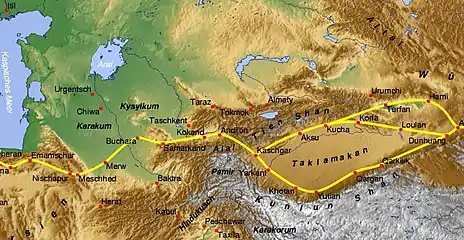

Tian Shan is north and west of the Taklamakan Desert and directly north of the Tarim Basin in the border region of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Xinjiang in Northwest China. In the south it links up with the Pamir Mountains and to north and east it meets the Altai Mountains of Mongolia.

In Western cartography as noted by the National Geographic Society, the eastern end of the Tian Shan is usually understood to be east of Ürümqi, with the range to the east of that city known as the Bogda Shan as part of the Tian Shan. Chinese cartography from the Han Dynasty to the present agrees, with the Tian Shan including the Bogda Shan and Barkol ranges.

The Tian Shan are a part of the Himalayan orogenic belt, which was formed by the collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates in the Cenozoic era. They are one of the longest mountain ranges in Central Asia and stretch some 2,900 kilometres (1,800 mi) eastward from Tashkent in Uzbekistan.[3]

The highest peak in the Tian Shan is Jengish Chokusu (also called Victory Peak) on the border of China. At 7,439 metres (24,406 ft) high, it is the highest point in Kyrgyzstan.[3] The Tian Shan's second highest peak, Khan Tengri (Lord of the Spirits), straddles the Kazakhstan-Kyrgyzstan border and at 7,010 metres (23,000 ft) is the highest point of Kazakhstan. Mountaineers class these as the two most northerly peaks over 7,000 metres (23,000 ft) in the world.

The Torugart Pass, at 3,752 metres (12,310 ft), is located at the border between Kyrgyzstan and China's Xinjiang province. The forested Alatau ranges, which are at a lower altitude in the northern part of the Tian Shan, are inhabited by pastoral tribes that speak Turkic languages.

The Tian Shan are separated from the Tibetan Plateau by the Taklimakan Desert and the Tarim Basin to the south.

The major rivers rising in the Tian Shan are the Syr Darya, the Ili River and the Tarim River. The Aksu Canyon is a notable feature in the northwestern Tian Shan.

Continuous permafrost is typically found in the Tian Shan starting at the elevation of about 3,500-3,700 m above the sea level. Discontinuous alpine permafrost usually occurs down to 2,700-3,300 m, but in certain locations, due to the peculiarity of the aspect and the microclimate, it can be found at elevations as low as 2,000 m.[9]

One of the first Europeans to visit and the first to describe the Tian Shan in detail was the Russian explorer Peter Semenov, who did so in the 1850s.

Glaciers in the Tian Shan Mountains have been rapidly shrinking and have lost 27%, or 5.4 billion tons annually, of its ice mass since 1961 compared to an average of 7% worldwide.[10] It is estimated that by 2050 half of the remaining glaciers will have melted.

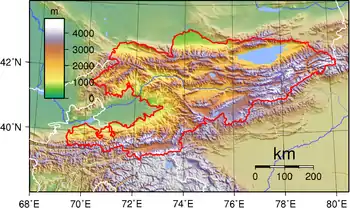

Ranges

The Tian Shan have a number of named ranges which are often mentioned separately (all distances are approximate).

In China the Tian Shan starts north of Kumul City (Hami) with the U-shaped Barkol Mountains, from about 600 to 400 kilometres (370 to 250 mi) east of Ürümqi. Then the Bogda Shan (god mountains) run from 350 to 40 kilometres (217 to 25 mi) east of Ürümqi. Then there is a low area between Ürümqi and the Turfan Depression. The Borohoro Mountains start just south of Ürümqi and run west-northwest 450 kilometres (280 mi) separating Dzungaria from the Ili River basin. Their north end abuts on the 200 kilometres (120 mi) Dzungarian Alatau which runs east northeast along Sino-Kazakh border. They start 50 kilometres (31 mi) east of Taldykorgan in Kazakhstan and end at the Dzungarian Gate. The Dzungarian Alatau in the north, the Borohoro Mountains in the middle and the Ketmen Range in the south make a reversed Z or S, the northeast enclosing part of Dzungaria and the southwest enclosing the upper Ili valley.

In Kyrgyzstan the mainline of the Tian Shan continues as Narat Range from the base of the Borohoros west 570 kilometres (350 mi) to the point where China, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan meet. Here is the highest part of the range – the Central Tian Shan, with Peak Pobeda (Kakshaal Too range) and Khan Tengri. West of this, the Tian Shan split into an 'eye', with Issyk Kul Lake in its center. The south side of the lake is the Terskey Alatau and the north side the Kyungey Ala-Too (shady and sunny Ala-Too). North of the Kyungey Ala-Too and parallel to it is the Trans-Ili Alatau in Kazakhstan just south of Almaty. West of the eye, the range continues 400 kilometres (250 mi) as the Kyrgyz Ala-Too, separating Chui Province from Naryn Oblast and then Kazakhstan from the Talas Province. This oblast is the upper valley of the Talas River, the south side of which is the 200 kilometres (120 mi) Talas Ala-Too Range ('Ala-too' is a Kirgiz spelling of Alatau). At the east end of the Talas Alatau the Suusamyr Too range runs southeast enclosing the Suusamyr Valley or plateau.

As for the area south of the Fergana Valley there is a 800 kilometres (500 mi) group of mountains that curves west-southwest from south of Issyk Kul Lake separating the Tarim Basin from the Fergana Valley. The Fergana Range runs northeast towards the Talas Ala-Too and separates the upper Naryn basin from Fergana proper. The southern side of these mountains merge into the Pamirs in Tajikistan (Alay Mountains and Trans-Alay Range). West of this is the Turkestan Range, which continues almost to Samarkand.

Ice Age

On the north margin of the Tarim basin between the mountain chain of the Kokshaal-Tau in the south and that one of the Terskey Alatau in the north there stretches the 100 to 120 km (62 to 75 mi) wide Tian Shan plateau with its set up mountain landscape. The Kokshaal-Tau continues with an overall length of 570 km (350 mi) from W of Pik Dankowa (Dankov, 5986 m) up to east-north-east to Pik Pobeda (Tumor Feng, 7439 m) and beyond it. This mountain chain as well as that of the 300 km long parallel mountain chain of the Terskey Alatau and the Tian Shan plateau situated in between, during glacial times were covered by connected ice-stream-networks and a plateau glacier. Currently, the interglacial remnant of this glaciation is formed by the only just 61 km long South Inylschek glacier. The outlet glacier tongues of the plateau glacier flowed to the north as far as down to Lake Issyk Kul (Lake) at 1605 (1609) m asl calving in this 160 km long lake.

In the same way, strong glaciation was in excess of 50 km wide in the high mountain area of the Kungey Alatau, connecting north of Issyk Kul and stretching as far as the mountain foreland near Alma Ata. The Kungey Alatau is 230 km long. Down from the Kungey Alatau the glacial glaciers also calved into the Issyk Kul lake. The Chon-Kemin valley was glaciated up to its inflow into the Chu valley.[11][12][13] From the west-elongation of the Kungey Alatau—that is the Kirgizskiy Alatau range (42°25′N/74–75°E)—the glacial glaciers flowed down as far as into the mountain foreland down to 900 m asl (close to the town Bishkek). Among others the Ak-Sai valley glacier has developed there a mountain foreland glacier.[11][14][13]

Altogether the glacial Tian Shan glaciation occupied an area of c. 118,000 square kilometres (46,000 sq mi). The glacier snowline (ELA) between the glacier feeding area and melting zone was about 1200m lower during the last ice age than it is today. Under the condition of a comparable precipitation ratio, there would result from this a depression of the average annual temperature of 7.2 to 8.4 °C for the Last Glacial Maximum compared with today.[11]

Ecology

The Tian Shan holds important forests of Schrenk's Spruce (Picea schrenkiana) at altitudes of over 2,000 metres (6,600 ft); the lower slopes have unique natural forests of wild walnuts and apples.[15]

The Tian Shan in its immediate geological past was kept from glaciation due to the "protecting" warm influence of the Indian Ocean monsoon climate. This defined its ecological features which could sustain its distinctive of the ecosphere. The mountains were subjected to constant geological changes with constantly evolving drainage systems which affected the patterns of vegetation, as well as exposing fertile soil for newly emerging seedlings to thrive in.

Ancestors of important crop vegetation were established and thrived in the area, among them: apricots (Prunus armeniaca), pears (Pyrus spp.), pomegranates (Punica granatum), figs (Ficus), cherries (Prunus avium) and mulberries (Morus). The Tian Shan region also included important animals like bear, deer and wild boar, which helped to spread seeds and expand the ecological diversity.

Among the vegetation colonizing the Tian Shan came, likely via birds from the east, the ancestors of what we know as the "sweet" apple. The fruit probably then looked like a tiny, long-stalked, bitter apple something like Malus baccata, the Siberian crab. The pips may have been carried in a bird's crop or clotted onto feet or feathers.

What natural features of the unique Tian Shan might have contributed to this rigorous selection program? Time is, as we have seen, not a problem. The turnover of individual trees is likewise conducive to the rapid evolution of a tree species, as is the fact that sweet apples are now, at least for all practical purposes, self-incompatible—that is, they cannot pollinate themselves. Therefore each apple tree within the forest and even each pip, usually five, within each individual fruit will be different. There are many apples on a mature tree, so natural selection has a rich and diverse population upon which to work. Birds, of course, eat all manner of fruit. But most birds eat seeds—a dietary feature not conducive either to the selection or spread of a fruit tree. Sweet apples are often eviscerated by birds, but the seeds are frequently left in the empty shell of the pome. The reason is that apple (and pear and quince) seeds are rich in cyanoglycosides, which are highly repellent, particularly to birds... Moreover, the placenta of the apple fruit, the womb, contains inhibitory substances that prevent the germination of the apple seed in situ. This is a commonly observed phenomenon in fruits as Michael Evenari showed in 1949. So what then does, or did, distribute the original apple seed? The bear...

— Barrie E. Juniper[16]

Climate

| Climate data for Tian Shan, 3639 m asl (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

5.2 (41.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

13.0 (55.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

13.3 (55.9) |

7.8 (46.0) |

2.3 (36.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −13.3 (8.1) |

−10.7 (12.7) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

0.5 (32.9) |

4.9 (40.8) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−11.3 (11.7) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −20.4 (−4.7) |

−18.8 (−1.8) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

3.2 (37.8) |

5.6 (42.1) |

5.2 (41.4) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−18.2 (−0.8) |

−6.7 (20.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −27.8 (−18.0) |

−26.7 (−16.1) |

−20.9 (−5.6) |

−13.6 (7.5) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−12.4 (9.7) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

−25.3 (−13.5) |

−13.6 (7.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −42 (−44) |

−44 (−47) |

−38.9 (−38.0) |

−31.7 (−25.1) |

−22 (−8) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−11 (12) |

−13 (9) |

−20 (−4) |

−34.7 (−30.5) |

−36.9 (−34.4) |

−40 (−40) |

−44 (−47) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 4.9 (0.19) |

8.1 (0.32) |

15.9 (0.63) |

20.8 (0.82) |

54.5 (2.15) |

68.4 (2.69) |

68.7 (2.70) |

48.9 (1.93) |

30.5 (1.20) |

18.5 (0.73) |

12.3 (0.48) |

10.8 (0.43) |

362.3 (14.27) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 1.78 | 3.18 | 5.46 | 6.92 | 10.92 | 12.78 | 11.98 | 9.58 | 7.40 | 5.18 | 3.74 | 3.29 | 82.21 |

| Source 1: Météo climat stats[17] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Météo Climat [18] | |||||||||||||

Religion

World Heritage Site

At the 2013 Conference on World Heritage, the eastern portion of Tian Shan in western China's Xinjiang Region was listed as a World Heritage Site.[19] The western portion in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan was then listed in 2016.[20]

Notes

- Chinese: 天山; pinyin: Tiānshān, Dungan: Тянсан, Tiansan; Old Turkic: 𐰴𐰣 𐱅𐰭𐰼𐰃, Tenğri tağ; Turkish: Tanrı Dağı; Mongolian: Тэнгэр уул, Tenger uul; Uighur: تەڭرىتاغ, Tengri tagh, Тәңри тағ; Kazakh: Тәңіртауы / Алатау, Táńirtaýy / Alataý, تٵڭٸرتاۋى / الاتاۋ; Kyrgyz: Теңир-Тоо / Ала-Тоо, Teñir-Too / Ala-Too, تەڭىر-توو / الا-توو; Uzbek: Tyan-Shan / Tangritog‘, Тян-Шан / Тангритоғ, تيەن-شەن / تەڭرىتاغ

References

- Prichard, James (1844), History of the Asiatic Nations, 3rd ed., Vol.IV, p. 281

- "Ensemble Tengir-Too". Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-89577-087-5.

- 班固 Ban Gu (2015-08-20). 漢書: 顏師古註 Hanshu: Yan Shigu Commentary.

祁連山即天山也,匈奴呼天為祁連 (translation: Qilian Mountain is the Tian Shan, the Xiongnu called the sky qilian)

- Liu, Xinru (2001), "Migration and Settlement of the Yuezhi-Kushan: Interaction and Interdependence of Nomadic and Sedentary Societies", Journal of World History, 12 (Issue 2, Fall 2001): 261–291, doi:10.1353/jwh.2001.0034, S2CID 162211306

- Mallory, J. P. & Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. London. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-500-05101-6.

- Prichard, James (1844), History of the Asiatic Nations, 3rd ed., Vol.IV, p. 281

- Wilkinson, Philip (2 October 2003). Myths and Legends. Stacey International. p. 163. ISBN 978-1900988612.

- Gorbunov, A.P. (1993), "Geocryology in Mt. Tianshan", PERMAFROST: Sixth International Conference. Proceedings. July 5–9, Beijing, China, 2, South China University of Technology Press, pp. 1105–1107, ISBN 978-7-5623-0484-5

- Naik, Gautam (August 17, 2015). "Central Asia Mountain Range Has Lost a Quarter of Ice Mass in 50 Years, Study Says". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- Kuhle, M. (1994). "New Findings on the Ice-cover between Issyk-Kul and K2 (Tian Shan, Karakorum) during the Last Glaciation". In Zheng Du; Zhang Qingsong; Pan Yusheng (eds.). Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Karakorum and Kunlun Mountains (ISKKM), Kashi, China, June 1992. Beijing: China Meteorological Press. pp. 185–197. ISBN 7-5029-1800-0.

- Grosswald, M. G.; Kuhle, M.; Fastook, J. L. (1994). "Würm Glaciation of Lake Issyk-Kul Area, Tian Shan Mts.: A Case Study in Glacial History of Central Asia". GeoJournal. 33 (2/3): 273–310. doi:10.1007/BF00812878. S2CID 140639502.

- Kuhle, M. (2004). "The High Glacial (Last Ice Age and LGM) glacier cover in High- and Central Asia. Accompanying text to the mapwork in hand with detailed references to the literature of the underlying empirical investigations". In Ehlers, J.; Gibbard, P. L. (eds.). Extent and Chronology of Glaciations. Vol. 3. Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 175–199. ISBN 0-444-51462-7.

- Kuhle, M.; Schröder, N. (2000). "New Investigations and Results on the Maximum Glaciation of the Kirgisen Shan and Tian Shan Plateau between Kokshaal Tau and Terskey Alatau". In Zech, W. (ed.). Pamir and Tian Shan. Contribution of the Quaternary History. International Workshop at the University of Bayreuth. Bayreuth, University Bayreuth. p. 8.

- Janik, Erika (October 25, 2011). "How the apple took over the planet". Salon.

- Juniper, Barrie E. (2007). "The Mysterious Origin of the Sweet Apple: On its way to a grocery counter near you, this delicious fruit traversed continents and mastered coevolution". American Scientist. 95 (1): 44–51. doi:10.1511/2007.63.44. JSTOR 27858899.

- "Moyennes 1961-1990 Kirghizistan (Asie)" (in French). Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- "Météo Climat stats for Tian Shan". Météo Climat. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- 新疆天山成功申遗

- "Western Tien-Shan". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- Bibliography

- The Contemporary Atlas of China. 1988. London: Marshall Editions Ltd. Reprint 1989. Sydney: Collins Publishers Australia.

- The Times Comprehensive Atlas of the World. Eleventh Edition. 2003. Times Books Group Ltd. London.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tian Shan. |

- Russian mountaineering site

- Tien Shan

- United Nations University (2009) digital video "Finding a place to feed: Kyrgyz shepherds & pasture loss": Shepherd shares family's observations and adaptation to the changing climate in highland pastures of Kyrgyzstan's Tian Shan mountains Accessed 1 December 2009