Turkish settlers in Northern Cyprus

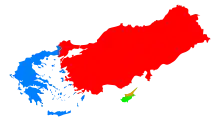

Turkish settlers in Northern Cyprus (Cypriot Turkish: Türkiyeliler,[1] "those from Turkey"), also referred to as Turkish immigrants (Turkish: Türkiyeli göçmenler[2]) are a group of mainland Turkish people who have settled in Northern Cyprus since the Turkish invasion in 1974. It is estimated that these settlers and their descendants (not including Turkish soldiers) now make up about half the population of Northern Cyprus.[3] The vast majority of the Turkish settlers were given houses and land that legally belong to Greek Cypriots by the government of Northern Cyprus, who is solely recognised by Turkey.[4] The group is heterogeneous in nature and is composed of various sub-groups, with varying degrees of integration. Mainland Turks are generally considered to be more conservative than the highly secularized Turkish Cypriots,[5][6] and tend to be more in favor of a two-state Cyprus.[7] However, not all settlers support nationalist policies.[8]

Legal issues

The presence of settlers in the island is one of the thorniest, most controversial issues in the ongoing negotiations to reunify Cyprus. The position of the internationally-recognised, Greek Cypriot-led[9] Republic of Cyprus and Greece, backed by United Nations resolutions, is that the settlement program is completely illegal under international law, as it violates the Fourth Geneva Convention (which prohibits an occupying power from willfully transferring its own population to the occupied area) and is a war crime.[10] The Republic of Cyprus and Greece thus demand that settlers be made to return to Turkey in a possible future solution to the Cyprus dispute; one of the main reasons that Greek Cypriots overwhelmingly rejected the 2004 Annan Plan was that the Annan plan allowed settlers to remain in Cyprus, and even allowed them to vote in the referendum for the proposed solution.[11] Both the Republic of Cyprus and Greece have therefore demanded that a future Cyprus settlement include the removal of settlers, or at least the greater part of them.[4][10]

Many settlers have severed their ties to Turkey, and their children consider Cyprus to be their homeland. There have been cases where settlers and their children returning to Turkey faced ostracism in their communities of origin. Thus, according to the Encyclopedia of Human Rights, "many others" argue that the settlers cannot be forcefully expelled from the island; in addition, and most observers think that a comprehensive future Cyprus settlement must "balance the overall legality of the settlement program with the human rights of the settlers".[12]

Sub-groups

Mainland Turks in Northern Cyprus are divided into two main groups: citizens and non-citizen residents.[13] Within the citizens, some have arrived in the island as a part of a settlement policy run by the Turkish and Turkish Cypriot authorities, some have migrated on their own and some have been born in the island to parents of either groups. Mete Hatay argues that only the first group has "good reason to be called settlers".[13]

The aforementioned sub-groups consist of several categories. The first group, citizens, can further be differentiated into skilled laborers and white-collar workers, Turkish soldiers and their close families, farmers who have settled in Cyprus and individual migrants.[14] The non-citizens can be divided into students and academic staff, tourists, workers with permits and illegitimate workers lacking permits.[15] Farmers settled from Turkey between 1975 and 1977 constitute the majority of the settler population.[8]

History

The policy of settling farmers in Cyprus began immediately after the 1974 invasion. Andrew Borowiec wrote of a Turkish announcement that 5000 agricultural workers would be settled to take up possessions left behind by the displaced Greek Cypriots.[16] According to Hatay, the first group of such settlers arrived on the island in February 1975; heavy settlement continued until 1977. These farmers originated from various regions of Turkey, including the Black Sea Region (Trabzon, Çarşamba, Samsun), the Mediterranean Region (Antalya, Adana, Mersin) and the Central Anatolia Region (Konya).[17] In February 1975, the number of "workers" from Turkey in the island was 910.[18]

The policy of settling farmers was conducted along the lines of the Agricultural Workforce Agreement signed by the Turkish Federated State of Cyprus (TFSC) and Turkey in 1975.[19] The consulates of the TFSC in Turkey were actively involved in organizing the transfer of this population; announcements through the radio and muhtars in villages called upon farmers interested in moving to Cyprus to apply to the consulates.[17] Many farmers who moved to Cyprus were from parts of Turkey with harsh living conditions or had to be displaced. This was the case with the village of Kayalar, where people from the Turkish Black Sea district of Çarşamba were moved. These people were displaced due to the flooding of their village by a dam that was built, and were given a choice between moving to Cyprus and other regions in Turkey; some chose Cyprus. Christos Ioannides argued that these people had no political motivations for this choice; interviews with some have indicated that some did not know the location of Cyprus before moving there.[17]

After the applications of the prospective settlers were approved, they were transported to the port of Mersin in buses specially arranged by the state. They exited Turkey using passports, one of which were issued for every family, and then took the ferry to cross the Mediterranean Sea to Cyprus. Once they arrived in Famagusta, they were initially accommodated briefly in empty hostels or schools, and then transferred to the Greek Cypriot villages, which were their destinations of settlement. The families were assigned houses by lot.[17]

The paperwork of these settlers were initially done in a way that would make them appear to be Turkish Cypriots returning to their homeland, to prevent accusations of violation of the Geneva Convention. Once the settlers arrived, Turkish Cypriot officers gathered them in the village coffeehouse, collected their personal information, and the settlers were assigned the closest Turkish Cypriot-inhabited village to their place of residence as their place of birth in their special identity cards that were subsequently produced. For example, a number of settlers in the Karpass Peninsula had the Turkish Cypriot village of Mehmetçik as their place of birth. When asked about the policy of settlement, İsmet Kotak, the Minister of Labor, Rehabilitation and Social Works of the TFSC, said that what was happening was an intense, rightful and legal return of Turkish Cypriots that had been forcefully driven out of the island. However, these special identity cards did not prove effective in achieving their mission and TFSC identity cards showing the settlers' actual place of birth were issued.[20]

Politics

| Part of a series on the Cyprus dispute |

| Cyprus peace process |

|---|

|

Despite the prevalent assumption that settlers helped maintain the right-wing National Unity Party's (UBP) decades-long power and consecutive electoral victories, this is incorrect, as between 1976 and 1993, the UBP received more votes in native than in settler villages. These trends were determined by the analysis of votes across several native and settler villages by the political scientist Mete Hatay. There was a political movement that was based on the representation of what they saw as the settlers' interests; this line of politics included the New Dawn Party (YDP) and Turkish Union Party (TBP). The majority of the vote in settler villages were divided between these settler parties and mainstream Turkish Cypriot opposition, including the Communal Liberation Party (TKP) and the Republican Turkish Party (CTP). Between 1992, when it was founded, and the election of 2003, which represented a shift away from it, the Democratic Party (DP) received the majority of settler opposition votes. Meanwhile, between 1990 and 2003, the UBP maintained a vote share averaging at around 40% at settler villages, but this was still less than the support it received in rural areas inhabited by native Turkish Cypriots. The UBP only received more support in settler villages in 1993 and after 2003, when it lost power. Furthermore, despite the prevalent assumption that the settlers advance the political interests of Turkey, settlers have voted against the line backed by Turkey at times, notably in 1990 against the Turkey-backed UBP and Rauf Denktaş and in 2004 against the Annan Plan for Cyprus.[21]

Notes

- "Türkiyeli-Kıbrıslı tartışması: "Kimliksiz Kıbrıslılar"" (in Turkish). Kıbrıs Postası. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- Uras, Umut. "Kıbrıs sorunu ve Türkiyeli göçmenler" (in Turkish). Al Jazeera. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- http://www.politico.eu/article/cyprus-reunification-peace-nicos-anastasiades-mustafa-akinci/

- Adrienne Christiansen, Crossing the Green Line: Anti-Settler Sentiment in Cyprus

- Bahcheli, Tozun; Noel, Sid (2013). "Ties that No Longer Bind: Greece, Turkey and the Fading Allure of Ethnic Kinship in Cyprus". In Mabry, Tristan James; McGarry, John; Moore, Margaret; et al. (eds.). Divided Nations and European Integration. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 326. ISBN 9780812244977.

- Fong, Mary; Chuang, Rueyling (2004). Communicating Ethnic and Cultural Identity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 282. ISBN 9780742517394.

- Tesser, Lynn (2013). Ethnic Cleansing and the European Union: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Security, Memory and Ethnography. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 117. ISBN 9781137308771.

- Ronen, Yaël (2011). Transition from Illegal Regimes under International Law. Cambridge University Press. pp. 231–245. ISBN 9781139496179.

- Kyris, George (2014). Ker-Lindsay, James (ed.). Resolving Cyprus: New Approaches to Conflict Resolution. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781784530006.

- Frank Hoffmeister, Legal Aspects of the Cyprus Problem: Annan Plan And EU Accession, pp. 56-59, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2006

- Letter by the President of the Republic, Mr Tassos Papadopoulos, to the U.N. Secretary-General, Mr Kofi Annan, dated 7 June, which circulated as an official document of the U.N. Security Council

- Encyclopedia of Human Rights, Volume 5. Oxford University Press. 2009. p. 460. ISBN 978-0195334029.

- Hatay 2005, p. 5

- Hatay 2005, p. 10

- Hatay 2005, p. 6

- Borowiec, Andrew (2000). Cyprus: A Troubled Island. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 98–99. ISBN 9780275965334.

- Hatay 2005, p. 12

- "Kıbrıs'ın Türk kesiminde toplam 1.010 işletme var". Milliyet. 9 February 1975. p. 9.

- Hacaloğlu, Hilmi; Tekşen, Özgür. "Kıbrıslı Türkler Türkiyelileri sevmez mi?" (in Turkish). Al Jazeera Turkish Journal. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- Şahin, Şahin & Öztürk 2013, p. 610–1

- Hatay 2005, pp. viii–ix

Bibliography

- Hatay, Mete (2005), Beyond Numbers: An Inquiry into the Political Integration of the Turkish 'Settlers' in Northern Cyprus (PDF), PRIO Cyprus Center, retrieved 30 August 2015

- Hatay, Mete (2008), "The Problem of Pigeons: Orientalism, Xenophobia and a Rhetoric of the "Local" in North Cyprus" (PDF), The Cyprus Review, 20 (2): 145–172

- Jensehaugen, Helge (2014), "The Northern Cypriot Dream – Turkish Immigration 1974–1980" (PDF), The Cyprus Review, 26 (2): 57–83

- Kurtuluş, Hatice; Purkıs, Semra (2014), Kuzey Kıbrıs'ta Türkiyeli Göçmenler (in Turkish), Istanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları

- Loizides, Neophytos (2011), "Contested migration and settler politics in Cyprus" (PDF), Political Geography, 30 (7): 391–401, doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.08.004

- Şahin, İsmail; Şahin, Cemile; Öztürk, Mine (2013), "Barış Harekâtı Sonrasında Türkiye'den Kıbrıs'a Yapılan Göçler ve Tatbik Edilen İskân Politikası" (PDF), Turkish Studies (in Turkish), 8 (7): 599–630, doi:10.7827/TurkishStudies.5225

- Talat Zrilli, Aysenur (2019), “Ethno-nationalism, state building and migration: the first wave of migration from Turkey to North Cyprus”, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 19 (3): 493-510, https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2019.1644047