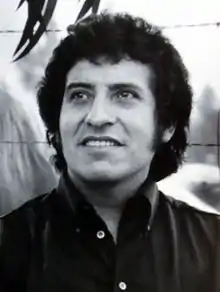

Víctor Jara

Víctor Lidio Jara Martínez (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈβiktoɾ ˈliðjo ˈxaɾa maɾˈtines]; 28 September 1932 – 16 September 1973)[1] was a Chilean teacher, theater director, poet, singer-songwriter and communist[2] political activist tortured and killed during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. He developed Chilean theater by directing a broad array of works, ranging from locally produced plays to world classics, as well as the experimental work of playwrights such as Ann Jellicoe. He also played a pivotal role among neo-folkloric musicians who established the Nueva Canción Chilena (New Chilean Song) movement. This led to an uprising of new sounds in popular music during the administration of President Salvador Allende.

Víctor Jara | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Víctor Lidio Jara Martínez |

| Born | 28 September 1932 San Ignacio, Chile |

| Origin | Chillán Viejo, Chile |

| Died | 16 September 1973 (aged 40) Santiago, Chile |

| Genres | Folk, Nueva canción, Andean music |

| Occupation(s) | Singer/songwriter, poet, theatre director, academic, social activist |

| Instruments | Vocals, Spanish guitar |

| Years active | 1959–1973 |

| Labels | EMI-Odeon DICAP/Alerce Warner Music Group |

| Associated acts | Violeta Parra, Patricio Castillo, Quilapayún, Inti-Illimani, Patricio Manns, Ángel Parra, Isabel Parra, Sergio Ortega, Pablo Neruda, Daniel Viglietti, Atahualpa Yupanqui, Joan Baez, Dean Reed, Silvio Rodríguez, Holly Near, Cornelis Vreeswijk |

| Website | FundacionVictorJara.org |

Jara was arrested shortly after the Chilean coup of 11 September 1973, which overthrew Allende. He was tortured during interrogations and ultimately shot dead, and his body was thrown out on the street of a shantytown in Santiago.[3] The contrast between the themes of his songs—which focused on love, peace, and social justice—and the brutal way in which he was murdered transformed Jara into a "potent symbol of struggle for human rights and justice" for those killed during the Pinochet regime.[4][5][6] His preponderant role as an open admirer and propagandist for Che Guevara and Allende's government, under which he served as a cultural ambassador through the late 60's and until the early 70's crisis that ended in the coup against Allende, marked him for death.

In June 2016, a Florida jury found former Chilean Army officer Pedro Barrientos liable for Jara's murder.[7][8] In July 2018, eight retired Chilean military officers were sentenced to 15 years and a day in prison for Jara's murder.[9]

Early life

Víctor Jara was born in 1932 to two farmers, Manuel Jara and Amanda Martínez. His exact place of birth is uncertain. For some, he was born in San Ignacio, near Chillán; but there are also rumors he could have been born in Quiriquina, one of the small towns nearby San Ignacio. In early childhood, moved with his family to Lonquén. His father was illiterate and encouraged his children to work from an early age to help the family survive, rather than attend school. By the age of 6, Jara was already working on the land. His father could not support the family on his earnings as a peasant at the Ruiz-Tagle estate, nor was he able to find stable work. He took to drinking and became increasingly violent. His relationship with his wife deteriorated, and he left the family to look for work when Víctor was still a child.

Jara's mother raised him and his siblings, and insisted that they get a good education. A mestiza with deep Araucanian roots in southern Chile, she was self-taught, and played the guitar and the piano. She also performed as a singer, with a repertory of traditional folk songs that she used for local functions like weddings and funerals.[10]

She died when Jara was 15, leaving him to make his own way. He began to study to be an accountant, but soon moved into a seminary, where he studied for the priesthood. After a couple of years, however, he became disillusioned with the Catholic Church and left the seminary. Subsequently, he spent several years in army service before returning to his hometown to pursue interests in folk music and theater.[11]

Artistic work

After joining the choir at the University of Chile in Santiago, Jara was convinced by a choir-mate to pursue a career in theater. He subsequently joined the university's theater program and earned a scholarship for talent.[11] He appeared in several of the university's plays, gravitating toward those with social themes, such as Russian playwright Maxim Gorky's The Lower Depths, a depiction of the hardships of lower-class life.[11]

In 1957, he met Violeta Parra, a singer who had steered folk music in Chile away from the rote reproduction of rural materials toward modern song composition rooted in traditional forms, and who had established musical community centers called peñas to incorporate folk music into the everyday life of modern Chileans. Jara absorbed these lessons and began singing with a group called Cuncumén, with whom he continued his explorations of Chile's traditional music.[11] He was deeply influenced by the folk music of Chile and other Latin American countries, and by artists such as Parra, Atahualpa Yupanqui, and the poet Pablo Neruda.

In the 1960s, Jara started specializing in folk music and sang at Santiago's La Peña de Los Parra, owned by Ángel Parra. Through these activities, he became involved in the Nueva Canción movement of Latin American folk music. He released his first album, Canto a lo humano, in 1966, and by 1970, he had left his theater work in favor of a career in music. His songs were inspired by a combination of traditional folk music and left-wing political activism. From this period, some of his best-known songs are "Plegaria a un Labrador" ("Prayer to a Worker") and "Te Recuerdo Amanda" ("I Remember You Amanda").

Political activism

Early in his recording career, Jara showed a knack for antagonizing conservative Chileans, releasing a traditional comic song called "La beata" that depicted a religious woman with a crush on the priest to whom she goes for confession. The song was banned on radio stations and removed from record shops, but the controversy only added to Jara's reputation among young and progressive Chileans.[12] More serious in the eyes of the Chilean right wing was Jara's growing identification with the socialist movement led by Salvador Allende. After visits to Cuba and the Soviet Union in the early 1960s, Jara had joined the Communist Party. The personal met the political in his songs about the poverty he had experienced firsthand.[12]

Jara's songs spread outside Chile and were performed by American folk artists.[13] His popularity was due not only to his songwriting skills but also to his exceptional power as a performer. He took a decisive turn toward political confrontation with his 1969 song "Preguntas por Puerto Montt" ("Questions About Puerto Montt"), which took direct aim at a government official who had ordered police to attack squatters in the town of Puerto Montt. The Chilean political situation deteriorated after the official was assassinated, and right-wing thugs beat up Jara on one occasion.[13]

In 1970, Jara supported Allende, the Popular Unity coalition candidate for president, volunteering for political work and playing free concerts.[14] He composed "Venceremos" ("We Will Triumph"), the theme song of Allende's Popular Unity movement, and welcomed Allende's election to the Chilean presidency in 1970. After the election, Jara continued to speak in support of Allende and played an important role in the new administration's efforts to reorient Chilean culture.[15]

He and his wife, Joan Jara, were key participants in a cultural renaissance that swept Chile, organizing cultural events that supported the country's new socialist government. He set poems by Pablo Neruda to music and performed at a ceremony honoring him after Neruda received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1972. Throughout rumblings of a right-wing coup, Jara held on to his teaching job at Chile's Technical University. His popular success during this time, as both a musician and a Communist, earned him a concert in Moscow. So successful was he that the Soviet Union tried to latch onto his popularity, claiming in their media that his vocal prowess was the result of surgery he had undergone while in Moscow.[16]

Backed by the United States, which opposed Allende's socialist politics, the Chilean military staged a coup d'état on September 11, 1973,[17] resulting in the death of Allende and the installation of Augusto Pinochet as dictator. At the moment of the coup, Jara was on his way to the Technical University (today the Universidad de Santiago). That night, he slept at the university along with other teachers and students, and sang to raise morale.

Torture and murder

After the coup, Pinochet's soldiers rounded up Chileans who were believed to be involved with leftist groups, including Allende's Popular Unity party. On the morning of 12 September 1973, Jara was taken prisoner, along with thousands of others, and imprisoned inside Chile Stadium.[18][19] The guards there tortured him, smashing his hands and fingers, and then mocked him by asking him to play the guitar. Jara instead sung the Chilean protest song Venceremos. Soon after, he was killed with a gunshot to the head, and his body was riddled with more than 40 bullets.[20]

According to the BBC.com[21] "There are many conflicting accounts of Jara’s last days but the 2019 Netflix documentary Massacre at the Stadium pieces together a convincing narrative. As a famous musician and prominent supporter of Allende, Jara was swiftly recognised on his way into the stadium. An army officer threw a lit cigarette on the ground, made Jara crawl for it, then stamped on his wrists. Jara was first separated from the other detainees, then beaten and tortured in the bowels of the stadium. At one point, he defiantly sang Venceremos (We Will Win), Allende’s 1970 election anthem, through split lips. On the morning of the 16th, according to a fellow detainee, Jara asked for a pen and notebook and scribbled the lyrics to Estadio Chile, which were later smuggled out of the stadium: “How hard it is to sing when I must sing of horror/ Horror which I am living, horror which I am dying.” Two hours later, he was shot dead, then his body was riddled with machine-gun bullets and dumped in the street. He was 40."

After his murder, Jara's body was displayed at the entrance of Chile Stadium for other prisoners to see. It was later discarded outside the stadium along with the bodies of other civilian prisoners who had been killed by the Chilean Army.[22] His body was found by civil servants and brought to a morgue, where one of them was able to identify him and contact his wife, Joan. She took his body and gave him a quick and clandestine burial in the general cemetery before she fled the country into exile.

Forty-two years later, former Chilean military officers were charged with his murder.[23]

Legal actions

On 16 May 2008, retired colonel Mario Manríquez Bravo, who was the chief of security at Chile Stadium as the coup was carried out, was the first to be convicted in Jara's death.[24] Judge Juan Eduardo Fuentes, who oversaw Bravo's conviction, then decided to close the case,[24] a decision Jara's family soon appealed.[24] In June 2008, Judge Fuentes re-opened the investigation and said he would examine 40 new pieces of evidence provided by Jara's family.[25][26]

On 28 May 2009, José Adolfo Paredes Márquez, a 54-year-old former Army conscript arrested the previous week in San Sebastián, Chile, was formally charged with Jara's murder. Following his arrest, on 1 June 2009, the police investigation identified the officer who had shot Jara in the head. The officer played Russian roulette with Jara by placing a single round in his revolver, spinning the cylinder, placing the muzzle against Jara's head, and pulling the trigger. The officer repeated this a couple of times until a shot fired and Jara fell to the ground. The officer then ordered two conscripts (one of them Paredes) to finish the job by firing into Jara's body. A judge ordered Jara's body to be exhumed in an effort to gather more information about his death.[27][28][29]

On 3 December 2009, Jara was reburied after a massive funeral in the Galpón Víctor Jara, across from Santiago's Plaza Brasil.[30]

On 28 December 2012, a judge in Chile ordered the arrest of eight former army officers for alleged involvement in Jara's murder.[31][32] He issued an international arrest warrant for one of them, Pedro Barrientos Núñez, the man accused of shooting Jara in the head during a torture session.

On 4 September 2013, Chadbourne & Parke attorneys Mark D. Beckett[33] and Christian Urrutia,[34] with the assistance of the Center for Justice and Accountability,[35] filed suit in a United States court against Barrientos, who lives in Florida, on behalf of Jara's widow and children. The suit accused Barrientos of arbitrary detention; cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment; extrajudicial killing; and crimes against humanity under the Alien Tort Statute (ATS), and of torture and extrajudicial killing under the Torture Victim Protection Act (TVPA). It alleged that Barrientos was liable for Jara's death as a direct perpetrator and as a commander.[22][36]

The specific claims were that:

- On 11 September 1973, troops from the Arica Regiment of the Chilean Army, specifically from La Serena, attacked the university where Jara taught. The troops prohibited civilians from entering or leaving the university premises. During the afternoon of 12 September 1973, military personnel entered the university and illegally detained hundreds of professors, students, and administrators. Víctor Jara was among those arbitrarily detained on the campus and was subsequently transferred to Chile Stadium, where he was tortured and killed.

- In the course of transporting and processing the civilian prisoners, Captain Fernando Polanco Gallardo, a commanding officer in military intelligence, recognized Jara as the well-known folk singer whose songs addressed social inequality, and who had supported President Allende's government. Captain Polanco separated Jara from the group and beat him severely. He then transferred Jara, along with some of the other civilians, to the stadium.

- Throughout his detention in the locker room of the stadium, Jara was in the physical custody of Lieutenant Barrientos, soldiers under his command, or other members of the Chilean Army who acted in accordance with the army's plan to commit human rights abuses against civilians.

- The arbitrary detention, torture, and extrajudicial killing of Jara and other detainees were part of a widespread, systematic attack on civilians by the Chilean Army from 11–15 September 1973. Barrientos knew, or should have known, about these attacks, if for no other reason than that he was present for and participated in them.[22]

On 15 April 2015, a US judge ordered Barrientos to stand trial in Florida.[37] On 27 June 2016, he was found liable for Jara's killing, and the jury awarded Jara's family $28 million.[38]

On 3 July 2018, eight retired Chilean military officers were sentenced to 15 years in prison for Jara's murder, and also the murder of his Communist associate and former Chilean prison director Littre Quiroga Carvajal.[39][40] They also received three extra years for kidnapping both men as well.[40] A ninth suspect was sentenced to five years in prison for covering up the murders as well.[39][40]

In November 2018, it was reported that a Chilean court ordered the extradition of Barrientos.[41]

Legacy

Joan Jara currently lives in Chile and runs the Víctor Jara Foundation,[42] which was established on 4 October 1994 with the goal of promoting and continuing Jara's work. She publicized a poem that Jara wrote before his death about the conditions of the prisoners in the stadium. The poem, written on a piece of paper that was hidden inside the shoe of a friend, was never named, but it is commonly known as "Estadio Chile". (Chile Stadium, now known as Víctor Jara Stadium,[43] is often confused with the Estadio Nacional, or National Stadium.)

Joan also distributed recordings of her husband's music, which became known worldwide. His music began to resurface in Chile in 1981. Nearly 800 cassettes of early, nonpolitical Jara songs[44] were confiscated on the "grounds that they violated an internal security law". The importer was given jail time but released six months later. By 1982, Jara's records were being openly sold throughout Santiago.[45]

Jara is one of many desaparecidos (people who vanished under the Pinochet government and were most likely tortured and killed) whose families are still struggling to get justice.[46] Thirty-six years after his first burial, he received a full funeral on 3 December 2009 in Santiago.[47] Thousands of Chileans attended his reburial, after his body was exhumed, to pay their respects. President Michelle Bachelet—also a victim of the Pinochet regime, having spent years in exile—said: "Finally, after 36 years, Victor can rest in peace. He is a hero for the left, and he is known worldwide, even though he continues buried in the general cemetery where his widow originally buried him."

Jara has been commemorated not only by Latin American artists, but also by global bands such as U2 and The Clash.[47] U2 has given concerts at Chile' National Stadium in homage not only to Jara, but also to the many others who suffered under the Pinochet dictatorship.

Although most of the master recordings of Jara's music were burned under Pinochet's military dictatorship, his wife managed to get recordings out of Chile, which were later copied and distributed worldwide. She later wrote an account of Jara's life and music titled Víctor: An Unfinished Song.

Since his death, Jara has been honored in numerous ways:

- Rolling Stone named him one of the fifteen top protest artists.[22]

- On 22 September 1973, less than two weeks after Jara's death, the Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh named a newly found asteroid 2644 Víctor Jara.

- The American folk singer Phil Ochs, who met and performed with Jara during a tour of South America, organized a benefit concert in his memory in New York in 1974. Titled "An Evening With Salvador Allende", the concert featured Ochs, Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, and Arlo Guthrie.

- The anthology For Neruda, for Chile contains a section called "The Chilean Singer", with poems dedicated to Jara.[48]

- An East German biographical movie called El Cantor ("The Singer") was made in 1978. It was directed by Jara's friend Dean Reed, who also played the part of Jara. That same year, the Dutch-Swedish singer-songwriter Cornelis Vreeswijk released an album of Jara songs translated into Swedish, Cornelis sjunger Victor Jara ("Cornelis sings Victor Jara").

- In 1989 Simple Minds dedicated Street Fighting Years track to Victor Jara.

- In the late 1990s, British actress Emma Thompson started to work on a screenplay that she planned to use as the basis for a movie about Jara. Thompson, a human rights activist and fan of Jara, saw his murder as a symbol of human rights violations in Chile, and believed a movie about his life and death would raise awareness.[49] The movie was to feature Antonio Banderas as Jara and Thompson as his wife, Joan.[50] However, the project was not completed.

- English poet Adrian Mitchell translated Jara's poems and lyrics and wrote the tribute "Víctor Jara", which Guthrie later set to music.

- The Soviet musician Alexander Gradsky created the rock opera Stadium (1985) based on the events surrounding Jara's death.[51]

- The Portuguese folk band Brigada Víctor Jara is named after him.

- Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band's Wrecking Ball Tour made a stop in Chile on 12 September 2013, just days before the 40th anniversary of Jara's death. Springsteen, guitarist Nils Lofgren and trumpet player Curt Ramm paid tribute to Jara by covering his song "Manifiesto", which Springsteen sang in Spanish. In a short speech before the song, Springsteen said (in Spanish): "In 1988, we played for Amnesty International in Mendoza, Argentina, but Chile was in our hearts. We met many families of desaparecidos, which had pictures of their loved ones. It was a moment that stays with me forever. If you are a political musician, Víctor Jara remains a great inspiration. It’s a gift to be here, and I take it with humbleness."[52]

In popular culture

- "Cancion Protesta" by Aterciopelados, a Colombian rock band, is a tribute to protest songs. The music video makes visual a quote from Jara, who said, "The authentic revolutionary should be behind the guitar, so that the guitar becomes an instrument of struggle, so that it can also shoot like a gun."

- "The Manifest - Epilogue" by the Israeli band Orphaned Land, a song from the 2018 album "Unsung Prophets & Dead Messiahs" features a quote from Victor Jara. The line is "Canto que ha sido valiente, Siempre será canción nueva".

- "I Thought I Heard Sweet Víctor Singing", a 2014 song by Paul Baker Hernandez (a British singer-songwriter living in Nicaragua), originated in Joan and Víctor Jara's garden in Santiago during events to cleanse Chile Stadium in 1990–91. The chorus goes: "Don't give up, don't give up, don't give up the struggle now. Keep on singing out for justice, don't give up the struggle now!" Baker Hernandez has written singing English interpretations of some of Victor's best-loved songs, such as 'Te Recuerdo Amanda', 'Plegaria a un labrador', and 'Ni Chicha Ni Limona'. He shares them with non-Spanish-speaking audiences during his frequent tours of the US/UK, and is currently (2017) recording a bi-lingual CD./ [53]

- In Barnstormer's album Zero Tolerance (2004), Attila the Stockbroker mentions Jara in the song "Death of a Salesman", written just after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center. "You were there in Chile, 11 September '73. 28 years to the day – what a dreadful irony. Victor Jara singing 'midst the tortured and the dead. White House glasses clinking as Allende's comrades bled."

- Belgian singer Julos Beaucarne relates Jara's death in his song "Lettre à Kissinger" ("Letter to Kissinger").[54]

- British musician Marek Black's record I Am A Train (2009) features the song "The Hands of Victor Jara".

- Chuck Brodsky also wrote and recorded a song called "The Hands of Victor Jara".[55] This 1996 tribute included the lyrics:

The blood of Victor Jara

Will never wash away

It just keeps on turning

A little redder every day

As anger turns to hatred

And hatred turns to guns

Children lose their fathersAnd mothers lose their sons

- In 1976, French singer fr: Jean-Max Brua dedicated to him a song called "Jara" on his album La Trêve de l’aube.

- The Turkish protest-rock band Bulutsuzluk Özlemi refer to Jara in their song "Şili'ye Özgürlük" ("Freedom to Chile"), part of their 1990 album Uçtu Uçtu.

- The Turkish jazz-rock band Mozaik published a song about Victor Jara, "Bir Adam Öldü" (A Man is Dead) in their 1990 album "Plastik Aşk".

- In 2004, Swiss singer fr: Michel Bühler released "Chanson pour Victor Jara" on his album Chansons têtues (EPM).

- The Tucson, Arizona-based band Calexico included a song called "Víctor Jara's Hands" on their 2008 album Carried to Dust.

- French singer Pierre Chêne also wrote a song about Jara's death, titled "Qui Donc Était Cet Homme?"

- The Clash sing about Jara in "Washington Bullets" on their 1980 triple album Sandinista!. Joe Strummer sings:

As every cell in Chile will tell, the cries of the tortured men. Remember Allende in the days before, before the army came. Please remember Victor Jara, in the Santiago Stadium. Es verdad, those Washington bullets again.

- "Decadencia", a song by Cuban rap group Eskuadron Patriota, mentions Jara in the line: "Como Víctor Jara diciéndole a su pueblo: La libertad está cerca".

- The Argentine rock group Los Fabulosos Cadillacs remember Jara in their song "Matador", with the lyrics "Que suenan/son balas/me alcanzan/me atrapan/resiste/Víctor Jara no calla" ("What is that sound/It's bullets/They reach me/They trap me/Resist/Víctor Jara is not silent").

- The German hip hop band Freundeskreis mention Jara in their song "Leg dein Ohr auf die Schiene der Geschichte" ("Put your ear on the rails of history"), released in 1997. The song also includes a short sample of Jara singing.

- The San Francisco post-rock band From Monument to Masses includes excerpts from a reading of Jara's "Estadio Chile" on the track "Deafening", a song from their 2005 remix album Schools of Thought Contend.

- In 1976, Arlo Guthrie included a biographical song titled "Victor Jara" on his album Amigo.[56] The lyrics were written by Adrian Mitchell, and the music by Guthrie.[57]

- American singer-songwriter Jack Hardy (1947–2011) mentioned Jara in "I Ought to Know", a song included on the album Omens in 2000.

- Heaven Shall Burn wrote and performed two songs about Jara and his legacy: "The Weapon They Fear" and "The Martyrs Blood".

- In 1975, the Swedish band Hoola Bandoola Band included the song "Victor Jara" on their album Fri information.

- The Chilean group Inti-Illimani dedicated the songs "Canto de las estrellas" and "Cancion a Víctor" to Jara.

- Welsh folk singer-songwriter Dafydd Iwan wrote a song called "Cân Victor Jara" ("Victor Jara's Song"), released on his 1979 album Bod yn rhydd ("Being free").

- Scottish singer-songwriter Bert Jansch wrote "Let Me Sing" about Jara.

- Belarusian composer Igor Lutchenok wrote "In memory of Victor Jara", with lyrics by Boris Brusnikov. It was first performed in 1974 by Belarusian singer Victor Vuyachich, and later by the Belarusian folk-rock group Pesniary, with an arrangement by Vladimir Mulyavin.

- American singer-songwriter Rod MacDonald wrote "The Death of Victor Jara" in 1991, with the refrain "the hands of the poet still forever wave." The song appears on his And Then He Woke Up record. MacDonald met Phil Ochs on the eve of Ochs' 1973 concert, and sang for him a song he had just written about the Chilean coup.[58]

- The title song on Rory McLeod's album Angry Love is about Jara.[59]

- In 2011, London-based band The Melodic released a track titled "Ode to Victor Jara" as the B-side to their limited-release vinyl single "Come Outside".

- Finnish punk rocker Pelle Miljoona mentions Jara in his song "Se elää".

- Irish folk artist Christy Moore included the song "Victor Jara" on his This Is The Day album.

- Holly Near's Sing to me the Dream is a tribute to Jara. The song "It Could Have Been Me" includes this verse:

"The Junta took the fingers from Victor Jara's hands.

Said to the gentle poet 'play your guitar now if you can.'

Well Victor started singing until they shot his body down.

You can kill a man, but not a song when it's sung the whole world round."

- In 1975, Norwegian folksinger Lillebjørn Nilsen included a tribute song titled "Victor Jara" in his album Byen Med Det Store Hjertet.

- "Ki an eimai rock",[60] a song released in 2011 by Greek rock singer Vasilis Papakonstantinou, refers to Jara.

- San Francisco ska-punk band La Plebe mentions Jara on their song "Guerra Sucia" from their album Brazo En Brazo.

- Venezuelan singer-songwriter Alí Primera wrote his "Canción para los valientes" ("Song to the Brave") about Jara. The song was included in an album of the same name in 1976.

- The Peruvian ska band Psicosis mentions Jara in their song "Esto es Ska". The chorus says, "Lo dijo Víctor Jara no nos puedes callar" ("Victor Jara said it, you can't silence us").

- The song "Broken Hands Play Guitars" by Rebel Diaz (a political hip-hop duo consisting of the Chilean brothers Rodrigo Venegas, known as RodStarz, and Gonzalo Venegas, known as G1), mixed by DJ Illanoiz, is a tribute to Jara.

- In 2014, Faroese soul-rock singer Högni Reistrup released the song "Back Against The Wall" on his album Call For a Revolution; the song is dedicated to Jara, whom Hogni was told about as a child by his father. The song portrays the horrors of Jara's torture, and his strength to withstand it. One line is:

"My voice is weak, just a whisper

My hands are broken

But I have written a letter

To remind my love

That she was born and raised

With her Back against the wall"

- Spanish singer Ismael Serrano mentioned Jara's name, and the name of his song "Te Recuerdo Amanda", in his own song, "Vine del Norte", on the 1998 album La Memoria de los Peces.[61]

- Scottish group Simple Minds released a 1989 album, Street Fighting Years, dedicated to Jara.

- Spanish ska group Ska-P dedicated a song called "Juan Sin Tierra" (originally written by Jorge Saldaña) to Jara. The chorus goes:

No olvidamos el valor de Víctor Jara |

We won't forget Victor Jara's courage |

- In Suren Tsormudian's "Ancestral Heritage" ("Наследие предков", Nasledye pryedkov), a 2012 entry in Universe of Metro 2033, Jara's fate is mentioned. However, the book repeats the common misconception that it was Estadio Nacional that was named after him.

- In 1987, U2 included the track "One Tree Hill" on their album The Joshua Tree, in which Bono sings: "And in the world, a heart of darkness, a fire zone/Where poets speak their heart, then bleed for it/Jara sang, his song a weapon in the hands of love/Though his blood still cries from the ground."

- Dutch-Swedish singer-songwriter Cornelis Vreeswijk recorded the album "Cornelis sings Victor Jara" (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cornelis_sjunger_Victor_Jara) in 1978 and later recorded "Blues för Victor Jara" on his album Bananer – bland annat in 1980.

- German singer Hannes Wader released his song "Victor Jara" on his album Wünsche (2001).

- The Scottish-Irish folk group The Wakes included a song called "Víctor Jara" on their album These Hands in 2008.

- Marty Willson-Piper, guitar player from The Church, included "Song for Victor Jara" on his 2009 solo album, Nightjar.

- British jazz-dance band Working Week's debut single "Venceremos (We Will Win)", from their 1985 album Working Nights, is a tribute to Jara.

- Former German folk duo Zupfgeigenhansel (Thomas Friz and Erich Schmeckenbecher) featured a live performance of their song "Victor Jara" as the last track on their 1978 LP Volkslieder III.

- James Dean Bradfield of Manic Street Preachers released a concept album about Victor Jara in 2020, called 'Even In Exile'.[62][21] In August 2020, a weekly three-part podcast, "Inspired By Jara" was released.[63][64] In the podcasts, James Dean Bradfield looks at the influence of Chilean musician and revolutionary singer Victor Jara on music, politics, cinema and ballet. Bradfield interviews people including Emma Thompson [who wrote a film script about him[65][66]], Calexico’s Joey Burns,[67] and Welsh folk singer Dafydd Iwan.[68][69]

- Fleet Foxes included a song titled "Jara" on their album Shore.[70]

- Punk/Hardcore band End on End named a song "Have You Ever Heard of Victor Jara" on their 2002 album, "Why Evolve When We can Go Sideways?"

- Hardcore band Stick To Your Guns released the song "Hasta La Victoria (Demo)" in honor of Victor Jara's birthday, through their BandCamp page.

Theater work

- 1959. Parecido à la Felicidad (Some Kind of Happiness), Alejandro Sieveking

- 1960. La Viuda de Apablaza (The Widow of Apablaza), Germán Luco Cruchaga (assistant director to Pedro de la Barra, founder of ITUCH) [71]

- 1960. The Mandrake, Niccolò Machiavelli

- 1961. La Madre de los Conejos (Mother Rabbit), Alejandro Sieveking (assistant director to Agustín Siré)

- 1962. Ánimas de Día Claro (Daylight Spirits), Alejandro Sieveking

- 1963. The Caucasian Chalk Circle, Bertolt Brecht (assistant director to Atahualpa del Cioppo)

- 1963. Los Invasores (The Intruders), Egon Wolff

- 1963. Dúo (Duet), Raúl Ruiz

- 1963. Parecido à la Felicidad, Alejandro Sieveking (version for Chilean television)

- 1965. La Remolienda, Alejandro Sieveking

- 1965. The Knack, Ann Jellicoe

- 1966. Marat/Sade, Peter Weiss (assistant director to William Oliver) [72]

- 1966. La Casa Vieja (The Old House), Abelardo Estorino

- 1967. La Remolienda, Alejandro Sieveking

- 1967. La Viuda de Apablaza, Germán Luco Cruchaga (director)

- 1968. Entertaining Mr Sloane, Joe Orton

- 1969. Viet Rock, Megan Terry

- 1969. Antigone, Sophocles

- 1972. Directed a ballet and musical homage to Pablo Neruda, which coincided with Neruda's return to Chile after being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Discography

Studio albums

| Year of release | Title |

|---|---|

| 1966 | Víctor Jara (Geografía) |

| 1967 | Canciones folklóricas de América (with Quilapayún) |

| 1967 | Víctor Jara |

| 1969 | Pongo en tus manos abiertas |

| 1970 | Canto libre |

| 1971 | El derecho de vivir en paz |

| 1972 | La Población |

| 1973 | Canto por travesura |

| 1974 (Estimated release) | Tiempos que cambian (unfinished) |

| 1974 | Manifiesto |

Live albums

- Víctor Jara en Vivo (1974)

- El Recital (1983)

- Víctor Jara en México, WEA International (1996)

- Habla y Canta en la Habana Cuba, WEA International (2001)

- En Vivo en el Aula Magna de la Universidad de Valparaíso, WEA International (2003)

Compilations

- Te recuerdo Amanda, Fonomusic (1974)

- Vientos del Pueblo, Monitor – U.S. (1976)

- Canto Libre, Monitor (1977)

- An Unfinished Song, Redwood Records (1984)

- Todo Víctor Jara, EMI (1992)

- 20 Años Después, Fonomusic (1992)

- The Rough Guide to the Music of the Andes, World Music Network (1996)

- Víctor Jara presente, colección "Haciendo Historia", Odeon (1997)

- Te Recuerdo, Víctor, Fonomusic (2000)

- Antología Musical, Warner Bros. Records (2001) 2CDs

- 1959–1969 – Víctor Jara, EMI Odeon (2001) 2CDs

- Latin Essential: Victor Jara, (WEA) 2CDs (2003)

- Colección Víctor Jara – Warner Bros. Records (2004) (8CD Box)

- Víctor Jara. Serie de Oro. Grandes Exitos, EMI (2005)

Tribute albums

- An Evening with Salvador Allende, VA – U.S. (1974) [73]

- A Víctor Jara, Raímon – Spain (1974)

- Het Recht om in Vrede te Leven, Cornelis Vreeswijk – Nederlands (1977)

- Hart voor Chili (various artists) (1977)

- Cornelis sjunger Victor Jara, Rätten till ett eget liv, Cornelis Vreeswijk – Sweden (1979)

- Omaggio a Victor Jara, Ricardo Pecoraro – Italy (1980)

- Quilapayún Canta a Violeta Parra, Víctor Jara y Grandes Maestros Populares, Quilapayún – Chile (1985)

- Konzert für Víctor Jara VA – Germany (1998)

- Inti-illimani performs Víctor Jara, Inti-Illimani – Chile (1999)

- Conosci Victor Jara?, Daniele Sepe – Italy (2001)

- Tributo a Víctor Jara, VA – Latin America/Spain (2004)

- Tributo Rock a Víctor Jara, VA – Argentina (2005)

- Lonquen: Tributo a Víctor Jara, Francesca Ancarola – Chile (2007)

- Even in Exile, James Dean Bradfield – UK (2020)

Documentaries and films

The following are films or documentaries about and/or featuring Víctor Jara:

- El Tigre Saltó y Mató, Pero Morirá…Morirá…. Director: Santiago Álvarez – Cuba (1973)

- Compañero: Víctor Jara of Chile. Directors: Stanley Foreman/Martin Smith (Documentary) – UK (1974)

- Il Pleut sur Santiago. Director: Helvio Soto – France/Bulgaria (1976)

- Ein April hat 30 Tage. Director: Gunther Scholz – East Germany (1978)

- El Cantor. Director: Dean Reed – East Germany (1978)

- El Derecho de Vivir en Paz. Director: Carmen Luz Parot – Chile (1999)

- Freedom Highway: Songs That Shaped a Century. Director: Philip King – Ireland (2001)

- La Tierra de las 1000 Músicas [Episode 6: La Protesta]. Directors: Luis Miguel González Cruz/Joaquín Luqui – Spain (2005)

- Phil Ochs: There But for Fortune Director: Kenneth Bowser (2010)

- Netflix - ReMastered: Massacre at the Stadium, (Netflix description) "The shocking murder of singer Victor Jara in 1973 turned him into a powerful symbol of Chile's struggle. Decades later, a quest for justice unfolds." January 11, 2019/ /1h 4m / Crime Documentaries

See also

Notes

- "Report of the Chilean Commission on Truth and Reconciliation Part III Chapter 1 (A.2)". usip.org. 10 April 2002. Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- Chilean Communist Party. "(History of the Chilean Communist Party (Reseña Histórica del Partido Comunista de Chile)" (PDF) (in Spanish). Chilean Communist Party. p. 1.

- Jara, Joan. Víctor: An Unfinished Song, 249-250

- "Jara v. Barrientos". Center for Justice and Accountability. 4 July 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- Charlotte Karrlsson-Willis (6 September 2013). "Family of Víctor Jara turns from Chile to US in quest for justice". The Santiago Times. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- Lynskey, Dorian. "Víctor Jara: The folk singer murdered for his music". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Former Chilean Army Officer Found Liable for 1973 Murder of Víctor Jara After U.S.-Backed Coup. Democracy Now! June 29, 2016.

- Peter Kornbluh (July 2016). Justice, Finally, for One of Pinochet’s Most Famous Victims. The Nation.

- "Victor Jara murder: ex-military officers sentenced in Chile for 1973 death". Reuters in Santiago via The Guardian. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Jara, Joan. Víctor: An Unfinished Song, 24-27

- "Victor Jara Biography - life, family, childhood, children, parents, death, wife, school". www.notablebiographies.com. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- "'They Couldn't Kill His Songs,'" BBC News, World: Americas]

- "Victor Jara," All Music Guide, http://www.allmusic.com (16 January 2007)

- Jara, Joan. Víctor: An Unfinished Song,

- Mularski, Jedrek. Music, Politics, and Nationalism in Latin America: Chile During the Cold War Era. Amherst: Cambria Press. ISBN 978-1-60497-888-9.

- Minkova, Yuliya (2013). OUR MAN IN CHILE, OR VICTOR JARA'S POSTHUMOUS LIFE IN SOVIET MEDIA AND POPULAR CULTURE. Virginia Tech. p. 608.

- Hitchens, Christopher (2001). The Trial of Henry Kissinger. New York: Twelve. p. 304. ISBN 978-1455522972.

- "Stadium's Renaming an Ode to Singer Martyred There". Los Angeles Times. 9 September 2003. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- "Victor Jara - Chilean musician". Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- Augustyn, Adam. "Victor Jara Chilean Musician." Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, n.d. Web. 9 December 2015. http://www.britannica.com/biography/Victor-Jara

- https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200812-vctor-jara-the-folk-singer-murdered-for-his-music

- "Complaint: Jara v. Barriento" (PDF). Official Florida court legal filing. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- "Former Chilean military officers charged in 1973 murder of singer Víctor Jara". The Guardian. 23 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- "Judge rules in Pinochet-era case of murdered singer". Stuff.co.nz. Reuters. 16 May 2008. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- "New probe into Victor Jara murder". BBC News. 4 June 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/victor-jara-former-pinochet-general-found-liable-torture-and-murder-celebrated-folk-singer-a7106811.html

- "Chilean singer Jara is exhumed". BBC. 4 June 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- "A oficial que ajustició a Víctor Jara, le decían "El Loco"". Red Nacion. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- Carroll, Rory. "Ex-Pinochet army conscript charged with folk singer Victor Jara's murder". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "Chile: A Proper Funeral for Víctor Jara". Global Voices Online. 5 December 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- Mariano Castillo (29 December 2012). "Charges brought in Chilean singer's death, 39 years later". CNN.

- "Ex-army officers implicated in Victor Jara death". BBC. 28 December 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- "Mark D. Beckett | Chadbourne & Parke LLP". www.chadbourne.com. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- "Christian Urrutia | Chadbourne & Parke LLP". www.chadbourne.com. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- "Clients | CJA". Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- "Jara v. Barrientos No. 3:13-cv-1075-J-99MMH-JBT (2013)". Center for Justice and Accountability. 4 September 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- "Victor Jara killing: Chile ex-army officer faces US trial". Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- Luscombe, Richard (27 June 2016). "Former Chilean military official found liable for killing of Victor Jara". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- De la Jara, Antonio; Laing, Aislinn (3 July 2018). "Eight Chilean military officers sentenced for singer Victor Jara's murder". Reuters. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- "Victor Jara killing: Nine Chilean ex-soldiers sentenced". BBC News. 4 July 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- Haberman, Clyde (18 November 2020). "He Died Giving A Voice to Chile's Poor. A Quest for Justice Took Decades". New York Times. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "FUNDACION VICTOR JARA". Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- Waldstein, David. The New York Times, 18 June 2015. Web. 9 December 2015. "In Chile’s National Stadium, Dark Past Shadows Copa América Matches"

- E., Morris, Nancy (1 July 1984). "Canto porque es necesario cantar: The New Song Movement in Chile, 1973-1983". Retrieved 20 July 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Morris, Nancy E. "Canto Porque Es Necesario Cantar; the New Song Movement in Chile, 1973-1983." Latin America Institute 16 (1984): n. pag. Web. 1 December 2015. http://repository.unm.edu/handle/1928/9709

- Henao, Luis A. (23 July 2015). "10 Former Chilean Soldiers Charged in Victor Jara Killing". The Washington Times. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- Long, Gideon. The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited, 5 December 2009. Web. 8 December 2015. "Murdered Chilean Folk Singer Laid to Rest after 36 Years"

- Lowenfels 1975, pp. 79–90.

- Stasio, Marilyn (Fall 1998). "Emma Thompson: The World's Her Stage". ontheissuesmagazine.com.

- Beatrice Sartori (7 January 1999). "Antonio Banderas se mete en la piel del poeta torturado". elmundo.es. Retrieved 3 February 2006.

- A website dedicated to the Alexander Gradsky's rock opera Stadium (Stadion) (in Russian)

- "Springsteen News". Backstreets.com. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- "Pense oir al dulce Victor en la noche cantar". Estribillo: 'No se rindan, no se rindan, no se rindan ya! A la justicia cantemos, no se rindan ya!'

- Julos Beaucarne – Lettre a Kissinger. 10 December 2011.

- "Music". Chuck Brodsky. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- Allmusic link

- Video on YouTube of Adrian Mitchell's poem "Victor Jara", with music by Arlo Guthrie, performed by Guthrie and his band Shenandoah in 1978

- "Rod MacDonald Band The Death Of Victor Jara". youtube.com. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- "Brief Descriptions of some of Rory's recorded and released songs". Rorymcleod.com. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- In Greek: Κι αν είμαι ροκ (lyrics: Dora Sitzani, music: Manos Loizos)

- "La memoria de los peces (1998)". Ismael Serrano. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/aug/16/james-dean-bradfield-even-in-exile-review-victor-jara-tribute-manic-street-preachers

- https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/inspired-by-jara/id1524301522

- https://podtail.com/en/podcast/inspired-by-jara/

- https://www.irishexaminer.com/lifestyle/arid-30115462.html

- https://srajavy.com/victor-jara-pdf-activities-netflix-resources-teachers-students/

- https://www.songfacts.com/facts/calexico/victor-jaras-hands

- https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-south-east-wales-27159932

- https://lab.org.uk/chile-in-wales-el-sueno-existe/

- https://genius.com/Fleet-foxes-jara-lyrics

- Instituto de Teatro de la Universidad de Chile (Theatre Institute of the University of Chile)

- Oliver, William (1967). "Marat/Sade in Santiago". Educational Theatre Journal. 19 (4): 486–501. doi:10.2307/3205029. JSTOR 3205029.

- An Evening with Salvador Allende was a recording of the Friends of Chile benefit concert held in New York City (1974) to honor Allende, Neruda and Víctor Jara. The double album appeared as a limited edition several years after the concert event; it was never reissued after its limited release. It featured Melanie, Bob Dylan, the Beach Boys, Phil Ochs and it was where Pete Seeger for the first time performed an English translation of Víctor Jara's last poem: Estadio Chile.

References

- Jara, Joan (1983). Victor: An Unfinished Song. Jonathan Cape, London. ISBN 0-224-01880-9

- Lowenfels, Walter (1975). For Neruda, for Chile: An International Anthology. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-6383-5. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- Kósichev, Leonard. (1990). La guitarra y el poncho de Víctor Jara. Progress Publishers, Moscow

External links

Resources in English

- Three chapters from Victor: An Unfinished Song by Joan Jara

- Discography

- Victor Jara: The Martyred Musician of Nueva Cancion Chilena

- Background materials on the Chilean Workers' Movement in the 1970s

- Report of the Chilean National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation

- GDR Poster Art: Víctor Jara

- "Who Killed Victor Jara?", Professor Paul Cantor, Norwalk Community College, Connecticut

- Allende’s Poet. Nick MacWilliam for Jacobin, August 2, 2016.

- Víctor Jara at IMDb

- El Cantor at IMDb