Vayelech

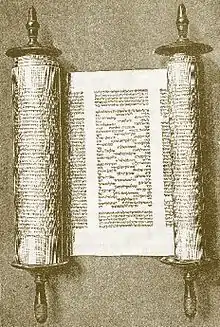

Vayelech, Vayeilech, VaYelech, Va-yelech, Vayelekh, Wayyelekh, Wayyelakh, or Va-yelekh (וַיֵּלֶךְ — Hebrew for "then he went out", the first word in the parashah) is the 52nd weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the ninth in the Book of Deuteronomy. It constitutes Deuteronomy 31:1–30. In the parashah, Moses told the Israelites to be strong and courageous, as God and Joshua would soon lead them into the Promised Land. Moses commanded the Israelites to read the law to all the people every seven years. God told Moses that his death was approaching, that the people would break the covenant, and that God would thus hide God's face from them, so Moses should therefore write a song to serve as a witness for God against them.

With just 30 verses, it has the fewest verses of any parashah, although not the fewest words or letters. (Parashat V'Zot HaBerachah has fewer letters and words.)[1] The parashah is made up of 5,652 Hebrew letters, 1,484 Hebrew words, 30 verses, and 112 lines in a Torah Scroll. Jews generally read it in September or early October (or rarely, in late August).[2] The lunisolar Hebrew calendar contains between 50 weeks in common years, and 54 or 55 weeks in leap years. In some leap years (for example, 2021, 2022, and 2025), Parashat Vayelech is read separately.[2] In common years (for example, 2020, 2023, 2024, 2026, and 2027), Parashat Vayelech is combined with the previous parashah, Nitzavim, to help achieve the number of weekly readings needed, and the combined portion is then read on the Sabbath immediately before Rosh Hashanah.[3] The two Torah portions are combined except when two Sabbaths fall between Rosh Hashanah and Sukkot and neither Sabbath coincides with a Holy Day.[4]

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot. In the Masoretic Text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashat Vayelech has two "open portion" (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter פ (peh)). The first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) spans the first four readings (עליות, aliyot). The second open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) spans the remaining three readings (עליות, aliyot). Within the first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah), a further subdivision, called a "closed portion" (סתומה, setumah) (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter ס (samekh)), spans the first two readings (עליות, aliyot).[5]

First reading — Deuteronomy 31:1–3

In the first reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses told the Israelites that he was 120 years old that day, could no longer go out and come in, and God had told him that he was not to go over the Jordan River.[6] God would go over before them and destroy the nations ahead of them, and Joshua would go over before them, as well.[7] The first reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[8]

Second reading — Deuteronomy 31:4–6

In the second reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses promised that God would destroy those nations as God had destroyed Sihon and Og, the kings of the Amorites, and the Israelites would dispossess those nations according to the commandments that Moses had commanded them.[9] Moses exhorted the Israelites to be strong and courageous, for God would go with them and would not forsake them.[10] The second reading (עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (סתומה, setumah) end here.[11]

Third reading — Deuteronomy 31:7–9

In the third reading (עליה, aliyah), in the sight of the people, Moses told Joshua to be strong and courageous, for he would go with the people into the land that God had sworn to their fathers and cause them to inherit it, and God would go before him, be with him, and not forsake him.[12] Moses wrote this law and delivered it to the priests, the sons of Levi, who bore the Ark of the Covenant and to all the elders of Israel.[13] The third reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[14]

Fourth reading — Deuteronomy 31:10–13

In the fourth reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses commanded them to read the law before all Israel at the end of every seven years during Sukkot, when all Israel was to appear in the place that God would choose.[15] Moses told them to assemble all the people — men, women, children, and strangers — that they might hear, learn, fear God, and observe the law as long as the Israelites lived in the land that they were going over the Jordan to possess.[16] The fourth reading (עליה, aliyah) and the first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) end here.[17]

Fifth reading — Deuteronomy 31:14–19

In the fifth reading (עליה, aliyah), God told Moses that as the day of his death was approaching, he should call Joshua, and they should present themselves in the tent of meeting so that God might bless Joshua.[18] God appeared in a pillar of cloud over the door of the Tent and told Moses that he was about to die, the people would rise up and break the covenant, God's anger would be kindled against them, God would forsake them and hide God's face from them, and many evils would come upon them.[19] God directed Moses therefore to write a song and teach it to the Israelites so that the song might serve as a witness for God against the Israelites.[20] The fifth reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[21]

Sixth reading — Deuteronomy 31:20–24

In the sixth reading (עליה, aliyah), God continued that when God will have brought the Israelites into the land flowing with milk and honey (חָלָב וּדְבַשׁ, chalav udevash), they will have eaten their fill, grown fat, turned to other gods, and broken the covenant, then when many evils will have come upon them, this song would testify before them as a witness.[22] So Moses wrote the song that day and taught it to the Israelites.[23] And God charged Joshua to be strong and courageous, for he would bring the Israelites into the land that God had sworn to them, and God would be with him.[24] And Moses finished writing the law in a book.[25] The sixth reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[26]

Seventh reading — Deuteronomy 31:25–30

In the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses commanded the Levites who bore the Ark of the Covenant to take the book and put it by the side of the Ark so that it might serves as a witness against the people.[27] For Moses said that he knew that even that day, the people had been rebelling against God, so how much more would they after his death?[28]

In the maftir (מפטיר) reading of Deuteronomy 31:28–30 that concludes the parashah,[29] Moses called the elders and officers to assemble, so that he might call heaven and earth to witness against them.[30] For Moses said that he knew that after his death, the Israelites would deal corruptly and turn away from the commandments, and evil would befall them because they would do that which was evil in the sight of God.[31] And Moses spoke to all the assembly of Israel the words of the song.[32] The seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), the second open portion (פתוחה, petuchah), and the parashah end here.[33]

Readings for Parashiot Nitzavim-Vayelech

When Jews read Parashat Nitzavim together with Parashat Vayelech, they divide readings according to the following schedule:[3]

| Reading | Verses |

|---|---|

| 1 | 29:9–28 |

| 2 | 30:1–6 |

| 3 | 30:7–14 |

| 4 | 30:15–31:6 |

| 5 | 31:7–13 |

| 6 | 31:14–19 |

| 7 | 31:20–30 |

| Maftir | 31:28–30 |

Readings according to the triennial cycle

In years when Jews read the parashah separately, Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the entire parashah according to the schedule of first through seventh readings in the text above. When Jews read Parashat Nitzavim together with Parashat Vayelech, Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle can read the parashah according to the following schedule.[34]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reading | 29:9–30:14 | 30:1–31:6 | 31:7–30 |

| 1 | 29:9–11 | 30:1–3 | 31:7–9 |

| 2 | 29:12–14 | 30:4–6 | 31:10–13 |

| 3 | 29:15–28 | 30:7–10 | 31:14–19 |

| 4 | 30:1–3 | 30:11–14 | 31:20–22 |

| 5 | 30:4–6 | 30:15–20 | 31:22–24 |

| 6 | 30:7–10 | 31:1–3 | 31:25–27 |

| 7 | 30:11–14 | 31:4–6 | 31:28–30 |

| Maftir | 30:11–14 | 31:4–6 | 31:28–30 |

Key words

Words used frequently in the parashah include: Moses (11 times),[35] go (10 times),[36] and Israel (10 times).[37]

In ancient parallels

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

Exodus 3:8 and 17, 13:5, and 33:3, Leviticus 20:24, Numbers 13:27 and 14:8, and Deuteronomy 6:3, 11:9, 26:9 and 15, 27:3, and 31:20 describe the Land of Israel as a land flowing "with milk and honey." Similarly, the Middle Egyptian (early second millennium BCE) tale of Sinuhe Palestine described the Land of Israel or, as the Egyptian tale called it, the land of Yaa: "It was a good land called Yaa. Figs were in it and grapes. It had more wine than water. Abundant was its honey, plentiful its oil. All kind of fruit were on its trees. Barley was there and emmer, and no end of cattle of all kinds."[38]

In inner-Biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[39]

Moses calls heaven and earth to serve as witnesses against Israel in Deuteronomy 4:26, 30:19, 31:28, and 32:1. Similarly, Psalm 50:4–5 reports that God "summoned the heavens above, and the earth, for the trial of His people," saying "Bring in My devotees, who made a covenant with Me over sacrifice!" Psalm 50:6 continues: "Then the heavens proclaimed His righteousness, for He is a God who judges."

Expressions like "hide My countenance" in Deuteronomy 31:17–18 and 32:20 also appear in Isaiah 8:17, Ezekiel 39:29, Micah 3:4, Psalms 13:2, 27:9, 30:8, 51:11, 69:17, 89:47, 102:3, 104:29, and 143:7, and Job 13:24.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[40]

Josephus reports that even slaves attended the public reading of the Torah.[41]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[42]

31:1–9 — "Be strong and courageous"

The Gemara interpreted Moses's words "I am a hundred and twenty years old this day" in Deuteronomy 31:2 to signify that Moses spoke on his birthday, and that he thus died on his birthday. Citing the words "the number of your days I will fulfill" in Exodus 23:26, the Gemara concluded that God completes the years of the righteous to the day, concluding their lives on their birthdays.[43]

A Midrash likened God to a bridegroom, Israel to a bride, and Moses, in Deuteronomy 31:9, to the scribe who wrote the document of betrothal. The Midrash noted that the Rabbis taught that documents of betrothal and marriage are written only with the consent of both parties, and the bridegroom pays the scribe's fee.[44] The Midrash then taught that God betrothed Israel at Sinai, reading Exodus 19:10 to say, "And the Lord said to Moses: ‘Go to the people and betroth them today and tomorrow.'" The Midrash taught that in Deuteronomy 10:1, God commissioned Moses to write the document, when God directed Moses, "Carve two tables of stone." And Deuteronomy 31:9 reports that Moses wrote the document, saying, "And Moses wrote this law." The Midrash then taught that God compensated Moses for writing the document by giving him a lustrous countenance, as Exodus 34:29 reports, "Moses did not know that the skin of his face sent forth beams."[45]

31:10–13 — reading the law

The Mishnah taught that the Israelites would postpone the great assembly required by Deuteronomy 31:10–12 if observing it conflicted with the Sabbath.[46]

The Gemara noted that the command in Deuteronomy 31:12 for all Israelites to assemble applied to women (as does the command in Exodus 12:18 to eat matzah on the first night of Passover), even though the general rule (stated in Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 34a) is that women are exempt from time-bound positive commandments. The Gemara cited these exceptions to support Rabbi Joḥanan's assertion that one may not draw inferences from general rules, for they often have exceptions.[47]

Rabbi Joḥanan ben Beroka and Rabbi Eleazar Hisma reported that Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah interpreted the words "Assemble the people, the men and the women and the little ones," in Deuteronomy 31:12 to teach that the men came to learn, the women came to hear, and the little children came to give a reward to those who brought them.[48]

The Gemara deduced from the parallel use of the word "appear" in Exodus 23:14 and Deuteronomy 16:15 (regarding appearance offerings) on the one hand, and in Deuteronomy 31:10–12 (regarding the great assembly) on the other hand, that the criteria for who participated in the great assembly also applied to limit who needed to bring appearance offerings. A Baraita deduced from the words "that they may hear" in Deuteronomy 31:12 that a deaf person was not required to appear at the assembly. And the Baraita deduced from the words "that they may learn" in Deuteronomy 31:12 that a mute person was not required to appear at the assembly. But the Gemara questioned the conclusion that one who cannot talk cannot learn, recounting the story of two mute grandsons (or others say nephews) of Rabbi Joḥanan ben Gudgada who lived in Rabbi's neighborhood. Rabbi prayed for them, and they were healed. And it turned out that notwithstanding their speech impediment, they had learned halachah, Sifra, Sifre, and the whole Talmud. Mar Zutra and Rav Ashi read the words "that they may learn" in Deuteronomy 31:12 to mean "that they may teach," and thus to exclude people who could not speak from the obligation to appear at the assembly. Rabbi Tanhum deduced from the words "in their ears" (using the plural for "ears") at the end of Deuteronomy 31:11 that one who was deaf in one ear was exempt from appearing at the assembly.[48]

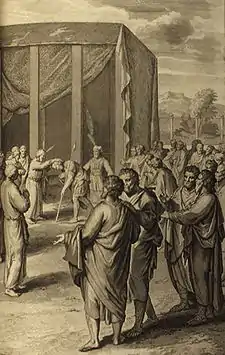

The Mishnah explained how the Jews of the Second Temple era interpreted the commandment of Deuteronomy 31:12 to "assemble the people . . . that they may hear . . . all the words of this law." At the conclusion of the first day of Sukkot immediately after the conclusion of the seventh year in the cycle, they erected a wooden dais in the Temple court, upon which the king sat. The synagogue attendant took a Torah scroll and handed it to the synagogue president, who handed it to the High Priest's deputy, who handed it to the High Priest, who handed it to the king. The king stood and received it, and then read sitting. King Agrippa stood and received it and read standing, and the sages praised him for doing so. When Agrippa reached the commandment of Deuteronomy 17:15 that "you may not put a foreigner over you" as king, his eyes ran with tears, but they said to him, "Don't fear, Agrippa, you are our brother, you are our brother!" The king would read from Deuteronomy 1:1 up through the shema (Deuteronomy 6:4–9), and then Deuteronomy 11:13–21, the portion regarding tithes (Deuteronomy 14:22–29), the portion of the king (Deuteronomy 17:14–20), and the blessings and curses (Deuteronomy 27–28). The king would recite the same blessings as the High Priest, except that the king would substitute a blessing for the festivals instead of one for the forgiveness of sin.[49]

A Baraita deduced from the parallel use of the words "at the end" in Deuteronomy 14:28 (regarding tithes) and 31:10 (regarding the great assembly) that just as the Torah required the great assembly to be done at a festival (Deuteronomy 31:10), the Torah also required tithes to be removed at the time of a festival.[50]

Tractate Sheviit in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpreted the laws of the Sabbatical year in Exodus 23:10–11, Leviticus 25:1–34, and Deuteronomy 15:1–18 and 31:10–13.[51] The Mishnah asked until when a field with trees could be plowed in the sixth year. The House of Shammai said as long as such work would benefit fruit that would ripen in the sixth year. But the House of Hillel said until Shavuot. The Mishnah observed that in reality, the views of two schools approximate each other.[52] The Mishnah taught that one could plow a grain-field in the sixth year until the moisture had dried up in the soil (that it, after Passover, when rains in the Land of Israel cease) or as long as people still plowed in order to plant cucumbers and gourds (which need a great deal of moisture). Rabbi Simeon objected that if that were the rule, then we would place the law in the hands of each person to decide. But the Mishnah concluded that the prescribed period in the case of a grain-field was until Passover, and in the case of a field with trees, until Shavuot.[53] But Rabban Gamaliel and his court ordained that working the land was permitted until the New Year that began the seventh year.[54] Rabbi Joḥanan said that Rabban Gamaliel and his court reached their conclusion on Biblical authority, noting the common use of the term "Sabbath" (שַׁבַּת, Shabbat) in both the description of the weekly Sabbath in Exodus 31:15 and the Sabbath-year in Leviticus 25:4. Thus, just as in the case of the Sabbath Day, work is forbidden on the day itself, but allowed on the day before and the day after, so likewise in the Sabbath Year, tillage is forbidden during the year itself, but allowed in the year before and the year after.[55]

Rabbi Isaac taught that the words of Psalm 103:20, "mighty in strength that fulfill His word," speak of those who observe the Sabbatical year (mentioned in Deuteronomy 31:10). Rabbi Isaac said that we often find that a person fulfills a precept for a day, a week, or a month, but it is remarkable to find one who does so for an entire year. Rabbi Isaac asked whether one could find a mightier person than one who sees his field untilled, see his vineyard untilled, and yet pays his taxes and does not complain. And Rabbi Isaac noted that Psalm 103:20 uses the words "that fulfill His word (dabar)," and Deuteronomy 15:2 says regarding observance of the Sabbatical year, "And this is the manner (dabar) of the release," and argued that "dabar" means the observance of the Sabbatical year in both places.[56]

Tractate Beitzah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws common to all of the Festivals in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:16; 34:18–23; Leviticus 16; 23:4–43; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–30:1; and Deuteronomy 16:1–17; 31:10–13.[57]

A Midrash cited the words of Deuteronomy 31:12, "And your stranger who is within your gates," to show God's injunction to welcome the stranger. The Midrash compared the admonition in Isaiah 56:3, "Neither let the alien who has joined himself to the Lord speak, saying: ‘The Lord will surely separate me from his people.'" (Isaiah enjoined Israelites to treat the convert the same as a native Israelite.) Similarly, the Midrash quoted Job 31:32, in which Job said, "The stranger did not lodge in the street" (that is, none were denied hospitality), to show that God disqualifies no creature, but receives all; the city gates were open all the time and anyone could enter them. The Midrash equated Job 31:32, "The stranger did not lodge in the street," with the words of Exodus 20:9 (20:10 in NJPS), Deuteronomy 5:13 (5:14 in NJPS), and Deuteronomy 31:12, "And your stranger who is within your gates" (which implies that strangers were integrated into the midst of the community). Thus the Midrash taught that these verses reflect the Divine example of accepting all creatures.[58]

31:14–30 — writing the law

Rabbi Joḥanan counted ten instances in which Scripture refers to the death of Moses (including three in the parashah), teaching that God did not finally seal the harsh decree until God declared it to Moses. Rabbi Joḥanan cited these ten references to the death of Moses: (1) Deuteronomy 4:22: "But I must die in this land; I shall not cross the Jordan"; (2) Deuteronomy 31:14: "The Lord said to Moses: ‘Behold, your days approach that you must die'"; (3) Deuteronomy 31:27: "[E]ven now, while I am still alive in your midst, you have been defiant toward the Lord; and how much more after my death"; (4) Deuteronomy 31:29: "For I know that after my death, you will act wickedly and turn away from the path that I enjoined upon you"; (5) Deuteronomy 32:50: "And die in the mount that you are about to ascend, and shall be gathered to your kin, as your brother Aaron died on Mount Hor and was gathered to his kin"; (6) Deuteronomy 33:1: "This is the blessing with which Moses, the man of God, bade the Israelites farewell before his death"; (7) Deuteronomy 34:5: "So Moses the servant of the Lord died there in the land of Moab, at the command of the Lord"; (8) Deuteronomy 34:7: "Moses was 120 years old when he died"; (9) Joshua 1:1: "Now it came to pass after the death of Moses"; and (10) Joshua 1:2: "Moses My servant is dead." Rabbi Joḥanan taught that ten times it was decreed that Moses should not enter the Land of Israel, but the harsh decree was not finally sealed until God revealed it to him and declared (as reported in Deuteronomy 3:27): "It is My decree that you should not pass over."[59]

Rabbi Jannai taught that when Moses learned that he was to die on that day, he wrote 13 scrolls of the law — 12 for the 12 tribes, and one which he placed in the Ark — so that if anyone should seek to forge anything in a scroll, they could refer back to the scroll in the Ark. Moses thought that he could busy himself with the Torah — the whole of which is life — and then the sun would set and the decree for his death would lapse. God signaled to the sun, but the sun refused to obey God, saying that it would not set and leave Moses alive in the world.[60]

Interpreting the words "call Joshua" in Deuteronomy 31:14, a Midrash taught that Moses asked God to let Joshua take over his office and nonetheless allow Moses continue to live. God consented on the condition that Moses treat Joshua as Joshua had treated Moses. So Moses rose early and went to Joshua's house. Moses called Joshua his teacher, and they set out walking with Moses on Joshua's left, like a disciple. When they entered the tent of meeting, the pillar of cloud came down and separated them. When the pillar of cloud departed, Moses asked Joshua what was revealed to him. Joshua asked Moses whether Joshua ever found out what God said to Moses. At that moment, Moses bitterly exclaimed that it would be better to die a hundred times than to experience envy, even once.[60]

The Gemara cited Deuteronomy 31:16 as an instance of where the Torah alludes to life after death. The Gemara related that sectarians asked Rabban Gamaliel where Scripture says that God will resurrect the dead. Rabban Gamaliel answered them from the Torah, the Prophets (נְבִיאִים, Nevi'im), and the Writings (כְּתוּבִים, Ketuvim), yet the sectarians did not accept his proofs. From the Torah, Rabban Gamaliel cited Deuteronomy 31:16, "And the Lord said to Moses, ‘Behold, you shall sleep with your fathers and rise up [again].'" But the sectarians replied that perhaps Deuteronomy 31:16 reads, "and the people will rise up." From the Prophets, Rabban Gamaliel cited Isaiah 26:19, "Your dead men shall live, together with my dead body shall they arise. Awake and sing, you who dwell in the dust: for your dew is as the dew of herbs, and the earth shall cast out its dead." But the sectarians rejoined that perhaps Isaiah 26:19 refers to the dead whom Ezekiel resurrected in Ezekiel 27. From the Writings, Rabban Gamaliel cited Song of Songs 7:9, "And the roof of your mouth, like the best wine of my beloved, that goes down sweetly, causing the lips of those who are asleep to speak." (As the Rabbis interpreted Song of Songs as a dialogue between God and Israel, they understood Song 7:9 to refer to the dead, whom God will cause to speak again.) But the sectarians rejoined that perhaps Song 7:9 means merely that the lips of the departed will move. For Rabbi Joḥanan said that if a halachah (legal ruling) is said in any person's name in this world, the person's lips speak in the grave, as Song 7:9 says, "causing the lips of those that are asleep to speak." Thus Rabban Gamaliel did not satisfy the sectarians until he quoted Deuteronomy 11:21, "which the Lord swore to your fathers to give to them." Rabban Gamaliel noted that God swore to give the land not "to you" (the Israelites whom Moses addressed) but "to them" (the Patriarchs, who had long since died). Others say that Rabban Gamaliel proved it from Deuteronomy 4:4, "But you who did cleave to the Lord your God are alive every one of you this day." And (the superfluous use of "this day" implies that) just as you are all alive today, so shall you all live again in the world to come. Similarly, the Romans asked Rabbi Joshua ben Hananiah from where can one prove that God will resurrect the dead and knows the future. Rabbi Joshua ben Hananiah replied that both are deduced from Deuteronomy 31:16, "And the Lord said to Moses, ‘Behold you shall sleep with your fathers, and rise up again; and this people shall go a whoring . . . ." The Romans replied that perhaps Deuteronomy 31:16 means that the Israelites "will rise up, and go a whoring." Rabbi Joshua ben Hananiah replied that if so, at least the Romans conceded that Deuteronomy 31:16 indicates that God knows the future. Similarly, Rabbi Joḥanan said on the authority of Rabbi Simeon ben Yoḥai that Deuteronomy 31:16 teaches that God will resurrect the dead and knows the future.[61]

Rabbi Jacob taught in Rabbi Aha's name (or others say in the Rabbi Abin's name) that no hour is as grievous as that in which God hides God's face (as foretold in Deuteronomy 31:17–18 and 32:20). Rabbi Jacob taught that since that hour, he had hoped for God, for God said in Deuteronomy 31:21, "For it shall not be forgotten out of the mouths of their seed."[62]

Rav Bardela bar Tabyumi taught in Rav's name that to whomever "hiding of the face"[63] does not apply is not one of the Children of Israel, and to whomever "they shall be devoured"[64] does not apply is also not one of them. The Rabbis confronted Rava, saying "hiding of the face" and "they shall be devoured" did not apply to Rava. Rava asked the Rabbis whether they knew how much he was forced to send secretly to the Court of King Shapur of Persia. Even so, the Rabbis directed their eyes upon Rava in suspicion. Meanwhile, the Court of King Shapur sent men who seized Rava's property. Rava then said that this bore out what Rabban Simeon ben Gamliel taught, that wherever the Rabbis direct their eyes in suspicion, either death or poverty follows. Interpreting "I will hide My face,"[63] Rava taught that God said although God would hide God's face from them, God would nonetheless speak to them in a dream. Rav Joseph taught that God's hand is nonetheless stretched over us to protect us, as Isaiah 51:16 says, "And I have covered you in the shadow of My hand." Rabbi Joshua ben Hanania was once at the Roman emperor Hadrian's court, when an unbeliever gestured to Rabbi Joshua in sign language that the Jewish people was a people from whom their God had turned His face. Rabbi Joshua ben Hanania gestured in reply that God's hand was stretched over the Jewish people. Emperor Hadrian asked Rabbi Joshua what unbeliever had said. Rabbi Joshua told the emperor what unbeliever had said and what Rabbi Joshua had replied. They then asked the unbeliever what he had said, and he told them. And then they asked what Rabbi Joshua had replied, and the unbeliever did not know. They decreed that a man who does not understand what he is being shown by gesture should hold converse in signs before the emperor, and they led him forth and executed him for his disrespect to the emperor.[65]

Rabbi Judah ben Simon expounded on the idea of God's hiding God's face. Rabbi Judah ben Simon compared Israel to a king's son who went into the marketplace and struck people but was not struck in return (because of his being the king's son). He insulted but was not insulted. He went up to his father arrogantly. But the father asked the son whether he thought that he was respected on his own account, when the son was respected only on account of the respect that was due to the father. So the father renounced the son, and as a result, no one took any notice of him. So when Israel went out of Egypt, the fear of them fell upon all the nations, as Exodus 15:14–16 reported, "The peoples have heard, they tremble; pangs have taken hold on the inhabitants of Philistia. Then were the chiefs of Edom frightened; the mighty men of Moab, trembling takes hold upon them; all the inhabitants of Canaan are melted away. Terror and dread falls upon them." But when Israel transgressed and sinned, God asked Israel whether it thought that it was respected on its own account, when it was respected only on account of the respect that was due to God. So God turned away from them a little, and the Amalekites came and attacked Israel, as Exodus 17:8 reports, "Then Amalek came, and fought with Israel in Rephidim," and then the Canaanites came and fought with Israel, as Numbers 21:1 reports, "And the Canaanite, the king of Arad, who dwelt in the South, heard tell that Israel came by the way of Atharim; and he fought against Israel." God told the Israelites that they had no genuine faith, as Deuteronomy 32:20 says, "they are a very disobedient generation, children in whom is no faith." God concluded that the Israelites were rebellious, but to destroy them was impossible, to take them back to Egypt was impossible, and God could not change them for another people. So God concluded to chastise and try them with suffering.[66]

Rava interpreted the words, "Now therefore write this song for you," in Deuteronomy 31:19 to create an obligation for every Jew to write a Torah scroll of one's own, even if one inherited a Torah scroll from one's parents.[67]

Rabbi Akiva deduced from the words "and teach it to the children of Israel" in Deuteronomy 31:19 that a teacher must go on teaching a pupil until the pupil has mastered the lesson. And Rabbi Akiva deduced from the words "put it in their mouths" immediately following in Deuteronomy 31:19 that the teacher must go on teaching until the student can state the lesson fluently. And Rabbi Akiva deduced from the words "now these are the ordinances that you shall put before them" in Exodus 21:1 that the teacher must wherever possible explain to the student the reasons behind the commandments. Rav Hisda cited the words "put it in their mouths" in Deuteronomy 31:19 for the proposition that the Torah can be acquired only with the aid of mnemonic devices, reading "put it" (shimah) as "its [mnemonic] symbol" (simnah).[68]

The Gemara reported a number of Rabbis' reports of how the Land of Israel did indeed flow with "milk and honey" (חָלָב וּדְבַשׁ, chalav udevash), as described in Exodus 3:8 and 17, 13:5, and 33:3, Leviticus 20:24, Numbers 13:27 and 14:8, and Deuteronomy 6:3, 11:9, 26:9 and 15, 27:3, and 31:20. Once when Rami bar Ezekiel visited Bnei Brak, he saw goats grazing under fig trees while honey was flowing from the figs, and milk dripped from the goats mingling with the fig honey, causing him to remark that it was indeed a land flowing with milk and honey. Rabbi Jacob ben Dostai said that it is about three miles from Lod to Ono, and once he rose up early in the morning and waded all that way up to his ankles in fig honey. Rabbi Simeon ben Lakish (Resh Lakish) said that he saw the flow of the milk and honey of Sepphoris extend over an area of sixteen miles by sixteen miles. Rabbah bar bar Hana said that he saw the flow of the milk and honey in all the Land of Israel and the total area was equal to an area of twenty-two parasangs by six parasangs.[69]

The Rabbis cited the prophecy of Deuteronomy 31:20 that "they shall have eaten their fill and grown fat, and turned to other gods" to support the popular saying that filling one's stomach ranks among evil things.[70]

In a Baraita, the Sages interpreted the words of Amos 8:12, "they shall run to and fro to seek the word of the Lord, and shall not find it," to mean that a woman would someday take a loaf of terumah bread and go from synagogue to academy to find out whether it was clean or unclean, but none would understand the law well enough to say. But Rabbi Simeon ben Yoḥai answered, Heaven forbid that the Torah could ever be forgotten in Israel, for Deuteronomy 31:21 says, "for it shall not be forgotten out of the mouths of their seed." Rather, the Gemara taught, one could interpret Amos 8:12, "they shall run to and fro to seek the word of the Lord, and shall not find it," to mean that they would not find a clear statement of the law or a clear Mishnah on point in any place.[71]

Resh Lakish read Deuteronomy 31:26, "Take this book of the law," to teach that the Torah was transmitted in its entirety as one book. Rabbi Joḥanan said in the name of Rabbi Bana'ah, however, that the Torah was transmitted in separate scrolls, as Psalm 40:8 says, "Then said I, 'Lo I am come, in the roll of the book it is written of me.'" The Gemara reported that Rabbi Joḥanan interpreted Deuteronomy 31:26, "Take this book of the law," to refer to the time after the Torah had been joined together from its several parts. And the Gemara suggested that Resh Lakish interpreted Psalm 40:8, "in a roll of the book written of me," to indicate that the whole Torah is called a "roll," as Zechariah 5:2 says, "And he said to me, 'What do you see?' And I answered, 'I see a flying roll.'" Or perhaps, the Gemara suggested, it is called "roll" for the reason given by Rabbi Levi, who said that God gave eight sections of the Torah, which Moses then wrote on separate rolls, on the day on which the Tabernacle was set up. They were: the section of the priests in Leviticus 21, the section of the Levites in Numbers 8:5–26 (as the Levites were required for the service of song on that day), the section of the unclean (who would be required to keep the Passover in the second month) in Numbers 9:1–14, the section of the sending of the unclean out of the camp (which also had to take place before the Tabernacle was set up) in Numbers 5:1–4, the section of Leviticus 16:1–34 (dealing with Yom Kippur, which Leviticus 16:1 states was transmitted immediately after the death of Aaron's two sons Nadab and Abihu), the section dealing with the drinking of wine by priests in Leviticus 10:8–11, the section of the lights of the menorah in Numbers 8:1–4, and the section of the red heifer in Numbers 19 (which came into force as soon as the Tabernacle was set up).[72]

.jpg.webp)

Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Judah differed over where relative to the Ark the Levites placed the Torah scroll mentioned in Deuteronomy 31:26. Rabbi Meir taught that the Ark contained the stone tablets and a Torah scroll. Rabbi Judah, however, taught that the Ark contained only the stone tablets, with the Torah scroll placed outside. Reading Exodus 25:17, Rabbi Meir noted that the Ark was 2½ cubits long, and as a standard cubit equals 6 handbreadths, the Ark was thus 15 handbreadths long. Rabbi Meir calculated that the tablets were 6 handbreadths long, 6 wide, and 3 thick, and were placed next to each other in the Ark. Thus the tablets accounted for 12 handbreadths, leaving 3 handbreadths unaccounted for. Rabbi Meir subtracted 1 handbreadth for the two sides of the Ark (½ handbreadth for each side), leaving 2 handbreadths for the Torah scroll. Rabbi Meir deduced that a scroll was in the Ark from the words of 1 Kings 8:9, "There was nothing in the Ark save the two tablets of stone that Moses put there." As the words "nothing" and "save" create a limitation followed by a limitation, Rabbi Meir followed the rule of Scriptural construction that a limitation on a limitation implies the opposite — here the presence of something not mentioned — the Torah scroll. Rabbi Judah, however, taught that the cubit of the Ark equaled only 5 handbreadths, meaning that the Ark was 12½ handbreadths long. The tablets (each 6 handbreadths wide) were deposited next to each other in the Ark, accounting for 12 handbreadths. There was thus left half a handbreadth, for which the two sides of the Ark accounted. Accounting next for width of the Ark, Rabbi Judah calculated that the tablets took up 6 handbreadths and the sides of the Ark accounted for ½ handbreadth, leaving 1 handbreadth. There Rabbi Judah taught were deposited the silver columns mentioned in Song 3:9–10,, "King Solomon made himself a palanquin of the wood of Lebanon, he made the pillars thereof of silver." At the side of the Ark was placed the coffer that the Philistines sent as a present, as reported in 1 Samuel 6:8, where the Philistine king said, "And put the jewels of gold which you return him for a guilt offering in a coffer by the side thereof, and send it away that it may go." And on this coffer was placed the Torah scroll, as Deuteronomy 31:26 says, "Take this book of the law, and put it by the side of the Ark of the Covenant of the Lord," demonstrating that the scroll was placed by the side of the Ark and not in it. Rabbi Judah interpreted the double limitation of 1 Kings 8:9, "nothing in the Ark save," to imply that the Ark also contained the fragments of the first tablets that Moses broke. The Gemara further explained that according to Rabbi Judah's theory, before the Philistine coffer came, the Torah scroll was placed on a ledge projecting from the Ark.[73]

Rabbi Ishmael cited Deuteronomy 31:27as one of ten a fortiori (kal va-chomer) arguments recorded in the Hebrew Bible: (1) In Genesis 44:8, Joseph's brothers told Joseph, "Behold, the money that we found in our sacks' mouths we brought back to you," and they thus reasoned, "how then should we steal?" (2) In Exodus 6:12, Moses told God, "Behold, the children of Israel have not hearkened to me," and reasoned that surely all the more, "How then shall Pharaoh hear me?" (3) In Deuteronomy 31:27, Moses said to the Israelites, "Behold, while I am yet alive with you this day, you have been rebellious against the Lord," and reasoned that it would follow, "And how much more after my death?" (4) In Numbers 12:14, "the Lord said to Moses: ‘If her (Miriam's) father had but spit in her face,'" surely it would stand to reason, "‘Should she not hide in shame seven days?'" (5) In Jeremiah 12:5, the prophet asked, "If you have run with the footmen, and they have wearied you," is it not logical to conclude, "Then how can you contend with horses?" (6) In 1 Samuel 23:3, David's men said to him, "Behold, we are afraid here in Judah," and thus surely it stands to reason, "How much more than if we go to Keilah?" (7) Also in Jeremiah 12:5, the prophet asked, "And if in a land of Peace where you are secure" you are overcome, is it not logical to ask, "How will you do in the thickets of the Jordan?" (8) Proverbs 11:31 reasoned, "Behold, the righteous shall be requited in the earth," and does it not follow, "How much more the wicked and the sinner?" (9) In Esther 9:12, "The king said to Esther the queen: ‘The Jews have slain and destroyed 500 men in Shushan the castle,'" and it thus stands to reason, "‘What then have they done in the rest of the king's provinces?'" (10) In Ezekiel 15:5, God came to the prophet saying, "Behold, when it was whole, it was usable for no work," and thus surely it is logical to argue, "How much less, when the fire has devoured it, and it is singed?"[74]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael counted 10 songs in the Tanakh: (1) the one that the Israelites recited at the first Passover in Egypt, as Isaiah 30:29 says, "You shall have a song as in the night when a feast is hallowed"; (2) the Song of the Sea in Exodus 15; (3) the one that the Israelites sang at the well in the wilderness, as Numbers 21:17 reports, "Then sang Israel this song: ‘Spring up, O well'"; (4) the one that Moses spoke in his last days, as Deuteronomy 31:30 reports, "Moses spoke in the ears of all the assembly of Israel the words of this song"; (5) the one that Joshua recited, as Joshua 10:12 reports, "Then spoke Joshua to the Lord in the day when the Lord delivered up the Amorites"; (6) the one that Deborah and Barak sang, as Judges 5:1 reports, "Then sang Deborah and Barak the son of Abinoam"; (7) the one that David spoke, as 2 Samuel 22:1 reports, "David spoke to the Lord the words of this song in the day that the Lord delivered him out of the hand of all his enemies, and out of the hand of Saul"; (8) the one that Solomon recited, as Psalm 30:1 reports, "a song at the Dedication of the House of David"; (9) the one that Jehoshaphat recited, as 2 Chronicles 20:21 reports: "when he had taken counsel with the people, he appointed them that should sing to the Lord, and praise in the beauty of holiness, as they went out before the army, and say, ‘Give thanks to the Lord, for His mercy endures for ever'"; and (10) the song that will be sung in the time to come, as Isaiah 42:10 says, "Sing to the Lord a new song, and His praise from the end of the earth," and Psalm 149:1 says, "Sing to the Lord a new song, and His praise in the assembly of the saints."[75]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[76]

According to the 12th century Spanish Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra, Moses went to each of the tribes separately, as they lay encamped, "to acquaint them that he was about to die, and that they might not be afraid, and to strengthen their hearts"[77]

Baḥya ibn Paquda noted that one person's understanding varies from time to time, and intellectual inspiration varies from person to person. But Baḥya taught that the exhortation of the Torah does not vary; it is the same for the child, the youth, one advanced in years, and the old, the wise and the foolish, even though the resulting practice varies from person to person. And so, Baḥya taught, Deuteronomy 31:12 is addressed to everyone: "Gather the people together, men and women, and children, and the stranger that is within your gate, that they may hear and that they may learn and fear the Lord your God . . . ." And Deuteronomy 31:11 says, "you shall read this law before all Israel in their hearing."[78]

Maimonides viewed the value of keeping festivals as plain: People derive benefit from assemblies, the emotions produced renew their attachment to religion, and the assemblies lead to friendly and social interaction among people. Reading Deuteronomy 31:12, "that they may hear, and that they may learn and fear the Lord," Maimonides concluded that this is especially the object of the commandment for people to gather on Sukkot.[79]

Maimonides taught that Scripture employs the idea of God's hiding God's face to designate the manifestation of a certain work of God. Thus, Moses the prophet foretold misfortune by saying (in God's words in Deuteronomy 31:17), "And I will hide My face from them, and they shall be devoured." For, Maimonides interpreted, when people are deprived of Divine protection, they are exposed to all dangers, and become the victim of circumstance, their fortune dependent on chance — a terrible threat.[80] Further, Maimonides taught that the hiding of God's face results from human choice. When people do not meditate on God, they are separated from God, and they are then exposed to any evil that might befall them. For, Maimonides taught, the intellectual link with God secures the presence of Providence and protection from evil accidents. Maimonides argued that this principle applies equally to an individual person and a whole community.[81]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Professor Ephraim Speiser of the University of Pennsylvania in the mid 20th century wrote that the word "Torah" (תּוֹרָה) is based on a verbal stem signifying “to teach, guide,” and the like, and the derived noun can carry a variety of meanings. Speiser argued that in Deuteronomy 31:26, the word refers to the long hortatory poem that follows, and cannot be mistaken for the title of the Pentateuch as a whole. Speiser asserted that Deuteronomy 31:9 is the only Pentateuchal passage that refers comprehensively to a written "Torah." Speiser argued that Deuteronomy 31:9 points either to the portions of Deuteronomy that precede (as most modern scholars conclude) or to the poetic sections that follow (as some scholars believe) and in neither case to the Pentateuch as a whole.[82]

Professor Jeffrey Tigay, who taught at the University of Pennsylvania from 1971 to 2010,[83] wrote that the public reading of the teaching required by Deuteronomy 31:12 demonstrates the democratic character of the Torah, which addresses its teachings and demands to all its adherents with few distinctions between priests and laity, and calls for universal education of the citizenry in law and religion.[84] Tigay wrote that the requirements of Deuteronomy 31:9–13 for Moses to write down the Teaching and have it read to the people every seven years culminate the exhortations of Moses to the people to learn the Teaching, to discuss it constantly, and to teach it to their children.[85] Tigay called the concern that this indicated to impress the Teaching on the mind of all Israelites "one of the most characteristic and far-reaching ideas of the Bible, particularly of Deuteronomy." Tigay argued that this concern reflects several premises and aims: (1) The Teaching is divinely inspired and authoritative. (2) The entire people, and not only a clerical elite, are God's children and consecrated to God. (3) The entire citizenry must be trained in the nature of justice so as to live in accordance with the law. And (4) The entire citizenry must know its rights and duties as well as those of its leaders, and that enables all to judge the leaders' actions.[86]

Professor Robert Alter of the University of California, Berkeley, citing the observation of David Cohen-Zenach, wrote that the assembly of the people required by Deuteronomy 31:12 to listen to the recitation of the Law was a reenactment of the first hearing of the Law at Mount Sinai, an event that Deuteronomy repeatedly calls[87] "the day of the assembly."[88]

The Kitzur Shulchan Aruch read Deuteronomy 31:19 to create a positive commandment to write a Torah scroll, even if one inherited a Torah scroll. One is considered to have fulfilled the commandment if one hires a scribe to write a Torah scroll, or buys it and finds that it is defective and corrects it. The Kitzur Shulchan Aruch forbade one to sell a Torah scroll, but in a case of great need, advised one to consult a competent Rabbi.[89] The Kitzur Shulchan Aruch said that it is also a commandment for every person to buy other sacred books — such as the Bible, the Mishnah, the Talmud, and codes of law — for learning, to study from them, and to lend them to others. If a person does not have the means to buy both a Torah scroll and other books for study, then the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch taught that the books for study take precedence.[90] The Kitzur Shulchan Aruch taught that one must treat such sacred books respectfully. It is forbidden to sit on this bench with them, unless the books are placed on something that is at least 3½ inches high, and it is forbidden to place them on the floor.[91] And the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch taught that one must not throw such books around nor place them upside down. If one finds such a book wrong side up, one should place it in the proper position.[92]

Dr. Nathan MacDonald of St John's College, Cambridge, reported some dispute over the exact meaning of the description of the Land of Israel as a "land flowing with milk and honey," as in Exodus 3:8 and 17, 13:5, and 33:3, Leviticus 20:24, Numbers 13:27 and 14:8, and Deuteronomy 6:3, 11:9, 26:9 and 15, 27:3, and 31:20. MacDonald wrote that the term for milk (חָלָב, chalav) could easily be the word for "fat" (חֵלֶב, chelev), and the word for honey (דְבָשׁ, devash) could indicate not bees' honey but a sweet syrup made from fruit. The expression evoked a general sense of the bounty of the land and suggested an ecological richness exhibited in a number of ways, not just with milk and honey. MacDonald noted that the expression was always used to describe a land that the people of Israel had not yet experienced, and thus characterized it as always a future expectation.[93]

In critical analysis

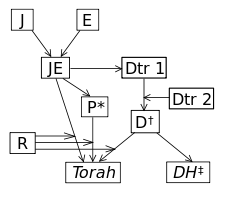

Some scholars who follow the Documentary Hypothesis find evidence of three separate sources in the parashah. Thus some scholars consider God's charges to Moses in Deuteronomy 31:14–15 and to Joshua in Deuteronomy 31:23 to have been composed by the Elohist (sometimes abbreviated E) who wrote in the north, in the land of the Tribe of Ephraim, possibly as early as the second half of the 9th century BCE.[94] Some scholars attribute to the first Deuteronomistic historian (sometimes abbreviated Dtr 1) two sections, Deuteronomy 31:1–13 and 24–27, which both refer to a written instruction, which these scholars identify with the scroll found in 2 Kings 22:8–13.[95] And then these scholars attribute the balance of the parashah, Deuteronomy 31:16–22 and 28–30, to the second Deuteronomistic historian (sometimes abbreviated Dtr 2) who inserted the Song of Moses (Deuteronomy 32:1–43) as an additional witness against the Israelites.[96]

While in the Masoretic Text and the Samaritan Pentateuch, Deuteronomy 31:1 begins, "And Moses went and spoke," in a Qumran scroll (1QDeutb), some Masoretic manuscripts, and the Septuagint, Deuteronomy 31:1 begins, "And Moses finished speaking all."[97] Robert Alter noted that the third-person forms of the verb "went," wayelekh, and the verb "finished," wayekhal, have the same consonants, and the order of the last two consonants could have been reversed in a scribal transcription. Alter argued that the Qumran version makes Deuteronomy 31:1 a proper introduction to Deuteronomy chapters 31–34, the epilogue of the book, as Moses had completed his discourses, and the epilogue thereafter concerns itself with topics of closure.[98]

In the Masoretic Text and the Samaritan Pentateuch, Deuteronomy 31:9 reports that Moses simply wrote down the Law, not specifying whether inscribed on tablets, clay, or papyrus. But a Qumran scroll (4QDeuth) and the Septuagint state that Moses wrote the Law "in a book." Martin Abegg Jr., Peter Flint, and Eugene Ulrich suggested that the verse may have reflected a growing emphasis on books of the Law after the Jews returned from the Babylonian exile.[99]

.jpg.webp)

Commandments

According to Maimonides and Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are two positive commandments in the parashah.[100]

- To assemble the people to hear Torah after the end of the Sabbatical year[101]

- For every Jew to write a Torah scroll[20]

Haftarah

When Parashat Vayelech is read separately, the haftarah for the parashah is Isaiah 55:6–56:8.

When Parashat Vayelech coincides with the special Sabbath Shabbat Shuvah (the Sabbath before Yom Kippur, as it does in 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022, and 2025), the haftarah is Hosea 14:2–10, Micah 7:18–20, and Joel 2:15–27.[2]

When Parashat Vayelech is combined with Parashat Nitzavim (as it is in 2020, 2023, 2024, 2026, and 2027), the haftarah is the haftarah for Nitzavim, Isaiah 61:10–63:9. That haftarah is the seventh and concluding installment in the cycle of seven haftarot of consolation after Tisha B'Av, leading up to Rosh Hashanah.

Notes

- "Devarim Torah Stats". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- "Parashat Vayeilech". Hebcal. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- "Parashat Nitzavim-Vayeilech". Hebcal. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- W. Gunther Plaut, The Torah: A Modern Commentary (New York: Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1981), page 1553.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, pages 196–203. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2009.

- Deuteronomy 31:1–2.

- Deuteronomy 31:3.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 196.

- Deuteronomy 31:4–5.

- Deuteronomy 31:6.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 197.

- Deuteronomy 31:7–8.

- Deuteronomy 31:9.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 198.

- Deuteronomy 31:10–11.

- Deuteronomy 31:12–13.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 199.

- Deuteronomy 31:14.

- Deuteronomy 31:15–18.

- Deuteronomy 31:19.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, pages 200–01.

- Deuteronomy 31:20–21.

- Deuteronomy 31:22.

- Deuteronomy 31:23.

- Deuteronomy 31:24–26.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 202.

- Deuteronomy 31:25–26.

- Deuteronomy 31:27.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, pages 202–03.

- Deuteronomy 31:28.

- Deuteronomy 31:29.

- Deuteronomy 31:30.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 203.

- See, e.g., Richard Eisenberg. "A Complete Triennial Cycle for Reading the Torah." Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement: 1986–1990, pages 383–418. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2001.

- Deuteronomy 31:1, 7, 9, 10, 14 (2 times), 16, 22, 24, 25, 30.

- Deuteronomy 31:2 (2 times), 3 (2 times), 6, 7, 8, 13, 16 (2 times).

- Deuteronomy 31:1, 7, 9, 11 (2 times), 19 (2 times), 22, 23, 30.

- Nathan MacDonald. What Did the Ancient Israelites Eat? Diet in Biblical Times, page 6. Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2008.

- For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer. "Inner-biblical Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1835–41. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- For more on early nonrabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Esther Eshel. "Early Nonrabbinic Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1841–59.

- Antiquities of the Jews book 4, chapter 8, paragraph 12. Circa 93–94, in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, page 117. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987.

- For more on classical rabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Yaakov Elman. "Classical Rabbinic Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1859–78.

- Babylonian Talmud Rosh Hashanah 11a (Sasanian Empire, 6th century), in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Beitza · Rosh Hashana. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 11, page 293. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2014.

- See Mishnah Bava Batra 10:4 (Land of Israel, circa 200 CE), in, e.g., Jacob Neusner, translator, The Mishnah: A New Translation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), page 580; Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 167b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Bava Basra: Volume 3, elucidated by Yosef Asher Weiss, edited by Hersh Goldwurm (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1994), volume 46, page 167b; see also Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 102b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Kesubos: Volume 3, elucidated by Abba Zvi Naiman, Avrohom Neuberger, Dovid Kamenetsky, Yosef Davis, Henoch Moshe Levin, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000), volume 28, page 102b; Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 9b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Kiddushin: Volume 1, elucidated by David Fohrman, Dovid Kamenetsky, and Hersh Goldwurm, edited by Hersh Goldwurm (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1992), volume 36, page 9b.

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 3:12 (Land of Israel, 9th century), in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 7, page 81.

- Mishnah Megillah 1:3, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 317. Babylonian Talmud Megillah 5a.

- Babylonian Talmud Eruvin 27a.

- Babylonian Talmud Chagigah 3a.

- Mishnah Sotah 7:8, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 459. Babylonian Talmud Sotah 41a.

- Jerusalem Talmud Maaser Sheni 53a. Land of Israel, circa 400 CE, in, e.g., The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009.

- Mishnah Sheviit 1:1–10:9, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 68–93. Tosefta Sheviit 1:1–8:11. Land of Israel, circa 300 CE, in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner and Louis E. Newman, volume 1, pages 203–49. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002. Jerusalem Talmud Sheviit 1a–87b, in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Elucidated by Avrohom Neuberger, David Azar, Dovid Nachfolger, Mordechai Smilowitz, Eliezer Lachman, Menachem Goldberger, Avrohom Greenwald, Michoel Weiner, Henoch Moshe Levin, Michael Taubes, Gershon Hoffman, Mendy Wachsman, Zev Meisels, and Abba Zvi Naiman; edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volumes 6a–b. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2006.

- Mishnah Sheviit 1:1, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 68.

- Mishnah Sheviit 2:1, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 70.

- Tosefta Sheviit 1:1, in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner and Louis E. Newman, volume 1, page 203.

- Babylonian Talmud Moed Katan 4a. Babylonia, 6th century, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Gedaliah Zlotowitz, Michoel Weiner, Noson Dovid Rabinowitch, and Yosef Widroff; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 21, pages 4a1–2. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1999.

- Leviticus Rabbah 1:1 (Land of Israel, 5th century), in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 4, page 2.

- Mishnah Beitzah 1:1–5:7, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 291–99. Tosefta Yom Tov (Beitzah) 1:1–4:11, in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, pages 585–604. Jerusalem Talmud Beitzah 1a–49b, in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volume 23. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2010. Babylonian Talmud Beitzah 2a–40b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Yisroel Reisman; edited by Hersh Goldwurm, volume 17. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1991.

- Exodus Rabbah 19:4 (10th century), in, e.g., Simon M. Lehrman, translator, Midrash Rabbah: Exodus (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 3, pages 231–34.

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 11:10, in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy, volume 7, page 180.

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 9:9, in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy, volume 7, page 162.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 90b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Asher Dicker, Joseph Elias, and Dovid Katz; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 49, pages 90b2–4. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1995.

- Genesis Rabbah 17:3, 42:3 (Land of Israel, 5th century), in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Genesis (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 1; Leviticus Rabbah 11:7, in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus, volume 4, pages 144–45; Esther Rabbah Prologue 11 (6th–12th centuries), in, e.g., Maurice Simon, translator, Midrash Rabbah: Esther (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 9; Ruth Rabbah Prologue 7 (6th–7th centuries), in, e.g., Larry Rabinowitz, translator, Midrash Rabbah: Ruth (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 8, pages 9, 11.

- Deuteronomy 31:17–18 and 32:20.

- Deuteronomy 31:17.

- Babylonian Talmud Chagigah 5a–b

- Ruth Rabbah Prologue 4, in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Ruth. Translated by L. Rabinowitz, volume 8, pages 7–8.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 21b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Asher Dicker and Asher Tzvi Naiman; edited by Hersh Goldwurm, volume 47, page 21b4. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1993.

- Babylonian Talmud Eruvin 54b.

- Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 111b–12a.

- Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 32a.

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 138b–39a.

- Babylonian Talmud Gittin 60a–b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Yitzchok Isbee and Mordechai Kuber; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, volume 35, pages 60a3–b1. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1993.

- Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 14a–b.

- Genesis Rabbah 92:7.

- Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael Shirata 1:5.

- For more on medieval Jewish interpretation, see, e.g., Barry D. Walfish. "Medieval Jewish Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1891–1915.

- Gill's Exposition of the Entire Bible on Deuteronomy 31, accessed 13 January 2016.

- Baḥya ibn Paquda, Chovot HaLevavot (Duties of the Heart), section 3, chapter 3 (Zaragoza, Al-Andalus, circa 1080), in, e.g., Bachya ben Joseph ibn Paquda, Duties of the Heart, translated by Yehuda ibn Tibbon and Daniel Haberman (Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1996), volume 1, pages 256–57.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed, part 3, chapter 46. Cairo, Egypt, 1190, in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, page 366. New York: Dover Publications, 1956.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed, part 1, chapter 23, in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, page 33.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed, part 3, chapter 51, in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, page 389.

- Ephraim A. Speiser, Genesis: Introduction, Translation, and Notes (New York: Anchor Bible, 1964), volume 1, pages xviii–xix.

- "Jeffrey H. Tigay". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- Jeffrey H. Tigay. The JPS Torah Commentary: Deuteronomy: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, page 291. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1996.

- Jeffrey H. Tigay. The JPS Torah Commentary: Deuteronomy: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, page 498. (citing Deuteronomy 4:9–10; 5:1; 6:6–9 and 20–25; and 11:18–20).

- Jeffrey H. Tigay. The JPS Torah Commentary: Deuteronomy: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, page 498.

- See Deuteronomy 9:10; 10:4; and 18:16.

- Robert Alter. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, page 1033. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2004.

- Shlomo Ganzfried, Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, siman 28, § 1 (Hungary, 1864), in, e.g., Eliyahu Meir Klugman and Yosaif Asher Weiss, editors, The Kleinman Edition: Kitzur Shulchan Aruch (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2008), volume 1, pages 304–05.

- Shlomo Ganzfried, Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, siman 28, § 2, in, e.g., Eliyahu Meir Klugman and Yosaif Asher Weiss, editors, Kleinman Edition: Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, volume 1, page 305.

- Shlomo Ganzfried, Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, siman 28, § 4, in, e.g., Eliyahu Meir Klugman and Yosaif Asher Weiss, editors, Kleinman Edition: Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, volume 1, page 306.

- Shlomo Ganzfried, Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, siman 28, § 6, in, e.g., Eliyahu Meir Klugman and Yosaif Asher Weiss, editors, Kleinman Edition: Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, volume 1, page 307.

- Nathan MacDonald. What Did the Ancient Israelites Eat? Diet in Biblical Times, page 7.

- See, e.g., Richard Elliott Friedman. The Bible with Sources Revealed, 4, 359. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 2003.

- See, e.g., Richard Elliott Friedman. The Bible with Sources Revealed, pages 5, 358–59, and note on page 359.

- See, e.g., Richard Elliott Friedman. The Bible with Sources Revealed, pages 359–60, and note on p. 359.

- Martin Abegg Jr., Peter Flint, and Eugene Ulrich. The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: The Oldest Known Bible Translated for the First Time into English, 188. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1999.

- Robert Alter. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, 1031. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2004.

- Martin Abegg Jr., Peter Flint, and Eugene Ulrich. The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible, 189.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah, Positive Commandments 16 and 17. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180, in Maimonides. The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, 1:23–25. London: Soncino Press, 1967. Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, 5:430–43. Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1988.

- Deuteronomy 31:12.

Further reading

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Biblical

- Jeremiah 30:1–3 (God's instruction to write).

Early nonrabbinic

- Testament of Moses. 1st century CE. Translated by J. Priest. In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Volume 1: Apocalyptic Literature and Testaments. Edited by James H. Charlesworth, pages 919–34. New York: Anchor Bible, 1983. ISBN 0-385-09630-5.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 4:8:12, 44. Circa 93–94. In, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, pages 117, 123–24. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

Classical rabbinic

- Mishnah: Sheviit 1:1–10:9; Beitzah 1:1–5:7; Megillah 1:3; Sotah 7:8. Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. In, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 68–93, 291–99, 317, 459. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Tosefta: Sheviit 1:1–8:11; Yom Tov (Beitzah) 1:1–4:11; Megillah 1:4; Chagigah 1:3; Sotah 7:9, 17; 11:6. Land of Israel, circa 300 CE. In, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, pages 203–49, 585–604, 636, 664, 862, 864, 878. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Sheviit 1a–87b; Terumot 7b; Maaser Sheni 53a; Yoma 31b; Beitzah 1a–49b; Chagigah 1a–b, 3a; Yevamot 69b; Sotah 16b, 36b; Gittin 31a; Avodah Zarah 1b, 14b. Tiberias, Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. In, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volumes 6a–7, 10, 21, 23, 27, 30, 36–37, 39, 47. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2006–2020. And in, e.g., The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009. ISBN 978-1-59856-528-7.

- Genesis Rabbah 42:3; 80:6; 92:7; 96:4, 96 (MSV). Land of Israel, 5th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 1, pages 342; volume 2, pages 739, 853, 886–87, 924, 926. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

.jpg.webp)

- Babylonian Talmud: Shabbat 138b; Eruvin 27a, 54b; Yoma 5b, 52b; Rosh Hashanah 11a, 12b; Megillah 5a; Moed Katan 2b, 17a, 28a; Chagigah 3a, 5a–b; Ketubot 111b–12a; Nedarim 38a; Sotah 13b, 41a; Gittin 59b–60a; Kiddushin 34a–b, 38a; Bava Batra 14a–15a; Sanhedrin 8a, 21b, 90b; Chullin 139b. Sasanian Empire, 6th Century. In, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 volumes. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Medieval

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 9:1–9. Land of Israel, 9th Century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Rashi. Commentary. Deuteronomy 31. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. In, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, volume 5, pages 319–28. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-89906-030-7.

- Rashbam. Commentary on the Torah. Troyes, early 12th century. In, e.g., Rashbam's Commentary on Deuteronomy: An Annotated Translation. Edited and translated by Martin I. Lockshin, page 169. Providence, Rhode Island: Brown Judaic Studies, 2004. ISBN 1-930675-19-4.

- Abraham ibn Ezra. Commentary on the Torah. Mid-12th century. In, e.g., Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Deuteronomy (Devarim). Translated and annotated by H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, volume 5, pages 224–31. New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 2001. ISBN 0-932232-10-8.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah, Introduction 2. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah (The Laws that Are the Foundations of the Torah), chapter 10, halachah 5. Egypt, circa 1170–1180. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah: The Laws [which Are] the Foundations of the Torah. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, volume 1, pages 292–95. New York: Moznaim Publishing, 1989. ISBN 978-0-940118-41-6.

- Hezekiah ben Manoah. Hizkuni. France, circa 1240. In, e.g., Chizkiyahu ben Manoach. Chizkuni: Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1198–201. Jerusalem: Ktav Publishers, 2013. ISBN 978-1-60280-261-2.

- Nachmanides. Commentary on the Torah. Jerusalem, circa 1270. In, e.g., Ramban (Nachmanides): Commentary on the Torah: Deuteronomy. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 5, pages 344–51. New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1976. ISBN 0-88328-010-8.

- Zohar 3:283a–86a. Spain, late 13th Century. In, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 volumes. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

- Bahya ben Asher. Commentary on the Torah. Spain, early 14th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbeinu Bachya: Torah Commentary by Rabbi Bachya ben Asher. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 7, pages 2754–73. Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2003. ISBN 965-7108-45-4.

- Isaac ben Moses Arama. Akedat Yizhak (The Binding of Isaac). Late 15th century. In, e.g., Yitzchak Arama. Akeydat Yitzchak: Commentary of Rabbi Yitzchak Arama on the Torah. Translated and condensed by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 912–13. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2001. ISBN 965-7108-30-6.

Modern

- Isaac Abravanel. Commentary on the Torah. Italy, between 1492–1509. In, e.g., Abarbanel: Selected Commentaries on the Torah: Volume 5: Devarim/Deuteronomy. Translated and annotated by Israel Lazar, pages 178–99. Brooklyn: CreateSpace, 2015. ISBN 978-1508721659.

- Obadiah ben Jacob Sforno. Commentary on the Torah. Venice, 1567. In, e.g., Sforno: Commentary on the Torah. Translation and explanatory notes by Raphael Pelcovitz, pages 984–91. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-89906-268-7.

- Moshe Alshich. Commentary on the Torah. Safed, circa 1593. In, e.g., Moshe Alshich. Midrash of Rabbi Moshe Alshich on the Torah. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 1122–30. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2000. ISBN 965-7108-13-6.

.jpg.webp)

- Avraham Yehoshua Heschel. Commentaries on the Torah. Cracow, Poland, mid 17th century. Compiled as Chanukat HaTorah. Edited by Chanoch Henoch Erzohn. Piotrkow, Poland, 1900. In Avraham Yehoshua Heschel. Chanukas HaTorah: Mystical Insights of Rav Avraham Yehoshua Heschel on Chumash. Translated by Avraham Peretz Friedman, pages 320–23. Southfield, Michigan: Targum Press/Feldheim Publishers, 2004. ISBN 1-56871-303-7.

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, 2:26; 3:33, 42; 4:46. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, pages 319, 418, 548, 687. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982. ISBN 0-14-043195-0.

.crop.jpg.webp)

- Chaim ibn Attar. Ohr ha-Chaim. Venice, 1742. In Chayim ben Attar. Or Hachayim: Commentary on the Torah. Translated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 5, pages 1982–90. Brooklyn: Lambda Publishers, 1999. ISBN 965-7108-12-8.

- Samson Raphael Hirsch. Horeb: A Philosophy of Jewish Laws and Observances. Translated by Isidore Grunfeld, pages 444–46. London: Soncino Press, 1962. Reprinted 2002 ISBN 0-900689-40-4. Originally published as Horeb, Versuche über Jissroel's Pflichten in der Zerstreuung. Germany, 1837.

.jpg.webp)

- Emily Dickinson. Poem 168 (If the foolish, call them "flowers" —). Circa 1860. Poem 597 (It always felt to me — a wrong). Circa 1862. In The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. Edited by Thomas H. Johnson, pages 79–80, 293–94. New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1960. ISBN 0-316-18414-4.

- Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal). Commentary on the Torah. Padua, 1871. In, e.g., Samuel David Luzzatto. Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1267–70. New York: Lambda Publishers, 2012. ISBN 965-524-067-3.

- Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter. Sefat Emet. Góra Kalwaria (Ger), Poland, before 1906. Excerpted in The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of Sefat Emet. Translated and interpreted by Arthur Green, pages 329–32. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1998. ISBN 0-8276-0650-8. Reprinted 2012. ISBN 0-8276-0946-9.

- Alexander Alan Steinbach. Sabbath Queen: Fifty-four Bible Talks to the Young Based on Each Portion of the Pentateuch, pages 164–68. New York: Behrman's Jewish Book House, 1936.

- Joseph Reider. The Holy Scriptures: Deuteronomy with Commentary, pages 286–97. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1937.

- Morris Adler. The World of the Talmud, page 37. B'nai B'rith Hillel Foundations, 1958. Reprinted Kessinger Publishing, 2007. ISBN 0-548-08000-3.

- Martin Buber. On the Bible: Eighteen studies, pages 80–92. New York: Schocken Books, 1968.

- J. Roy Porter. "The Succession of Joshua." In Proclamation and Presence: Old Testament Essays in Honour of Gwynne Henton Davies. Edited by John I. Durham and J. Roy Porter, pages 102–32. London: SCM Press, 1970. ISBN 0-334-01319-4.

- Bernard Grossfeld. “Targum Neofiti 1 to Deut 31:7.” Journal of Biblical Literature, volume 91 (number 4) (December 1972): pages 533–34.

- Michael Klein. “Deut 31:7, תבוא or תביא?” Journal of Biblical Literature, volume 92 (number 4) (December 1973): pages 584–85.

- Alexander Rofe. "The Composition of Deuteronomy 31 in the Light of a Conjecture about Inversion in the Order of Columns in the Biblical Text." Shnaton, volume 3 (1979): pages 59–76.

- Philip Sigal. "Responsum on the Status of Women: With Special Attention to the Questions of Shaliah Tzibbur, Edut and Gittin." New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1984. OH 53:4.1984. In Responsa: 1980–1990: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by David J. Fine, pages 11, 15, 21, 32, 35. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2005. ISBN 0-916219-27-5. (implications of the commandment for women to assemble for women's rights to participate equally in Jewish public worship).

- Pinchas H. Peli. Torah Today: A Renewed Encounter with Scripture, pages 233–37. Washington, D.C.: B'nai B'rith Books, 1987. ISBN 0-910250-12-X.

- Joel Roth. "The Status of Daughters of Kohanim and Leviyim for Aliyot." New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1989. OH 135:3.1989a. In Responsa: 1980–1990: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by David J. Fine, pages 49, 51. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2005. ISBN 0-916219-27-5. (implications for aliyot of the report that "Moses wrote this law, and delivered it to the priests the sons of Levi").

- Patrick D. Miller. Deuteronomy, pages 216–26. Louisville: John Knox Press, 1990.

- Mark S. Smith. The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, pages 10, 149. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990. ISBN 0-06-067416-4. (Deuteronomy 31:14–15; 24–26).

- Lawrence H. Schiffman. "The New Halakhic Letter (4QMMT) and the Origins of the Dead Sea Sect." Biblical Archaeologist. Volume 53 (number 2) (June 1990): pages 64–73.

- A Song of Power and the Power of Song: Essays on the Book of Deuteronomy. Edited by Duane L. Christensen. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 1993. ISBN 0-931464-74-9.

- Judith S. Antonelli. "Women and the Torah." In In the Image of God: A Feminist Commentary on the Torah, pages 489–93. Northvale, New Jersey: Jason Aronson, 1995. ISBN 1-56821-438-3.

- Richard Elliott Friedman. The Disappearance of God: A Divine Mystery. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1995. ISBN 0-316-29434-9.

- Aaron Demsky. "Who Returned First — Ezra or Nehemiah?" Bible Review, volume 12 (number 2) (April 1996).

- Ellen Frankel. The Five Books of Miriam: A Woman's Commentary on the Torah, pages 295–97. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1996. ISBN 0-399-14195-2.

- Richard Elliott Friedman. The Hidden Face of God. New York: Harper San Francisco, 1996. ISBN 0-06-062258-X.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Haftarah Commentary, pages 510–17. New York: UAHC Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8074-0551-5.

- Jeffrey H. Tigay. The JPS Torah Commentary: Deuteronomy: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, pages 289–98, 498–507. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1996. ISBN 0-8276-0330-4.

- Sorel Goldberg Loeb and Barbara Binder Kadden. Teaching Torah: A Treasury of Insights and Activities, pages 340–44. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-86705-041-1.

- Baruch J. Schwartz. "What Really Happened at Mount Sinai? Four biblical answers to one question." Bible Review, volume 13 (number 5) (October 1997).

- E. Talstra. "Deuteronomy 31: Confusion or Conclusion? The Story of Moses' Three-fold Succession." In Deuteronomy and Deuteronomic Literature: Festschrift C.H.W. Brekelmans. Edited by M. Vervenne and J. Lust, pages 87–110. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 1997. ISBN 9068319361.

- William H.C. Propp. "Why Moses Could Not Enter The Promised Land." Bible Review, volume 14 (number 3) (June 1998).

- Michael M. Cohen. "Insight: Did Moses Enter the Promised Land?" Bible Review. Volume 15 (number 6) (December 1999).

- Rosette Barron Haim. "Guardians of the Tradition." In The Women's Torah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Torah Portions. Edited by Elyse Goldstein, pages 384–89. Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2000. ISBN 1-58023-076-8.