Devarim (parsha)

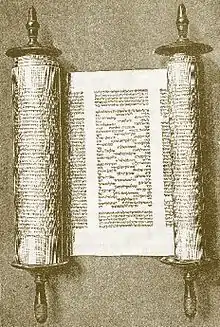

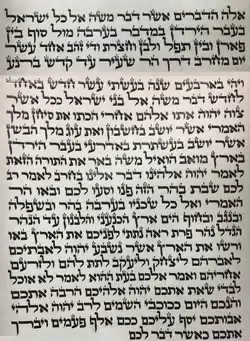

Devarim, D'varim, or Debarim (דְּבָרִים — Hebrew for "things" or "words," the second word, and the first distinctive word, in the parashah) is the 44th weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the first in the Book of Deuteronomy. It constitutes Deuteronomy 1:1–3:22. The parashah recounts how Moses appointed chiefs, the episode of the Twelve Spies, encounters with the Edomites and Ammonites, the conquest of Sihon and Og, and the assignment of land for the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and Manasseh.

The parashah is made up of 5,972 Hebrew letters, 1,548 Hebrew words, 105 verses, and 197 lines in a Torah Scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1] Jews generally read it in July or August. It is always read on Shabbat Chazon, the Sabbath just before Tisha B'Av.

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot. In the masoretic text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashat Devarim has no "open portion" (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter פ (peh)), and thus can be considered one whole unit. Parashat Devarim has five subdivisions, called "closed portions" (סתומה, setumah) (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter ס (samekh)). The first closed portion spans the first four readings, the fifth reading contains the next three closed portions, and the final closed portion spans the sixth and seventh readings.[2]

First reading — Deuteronomy 1:1–10

.jpg.webp)

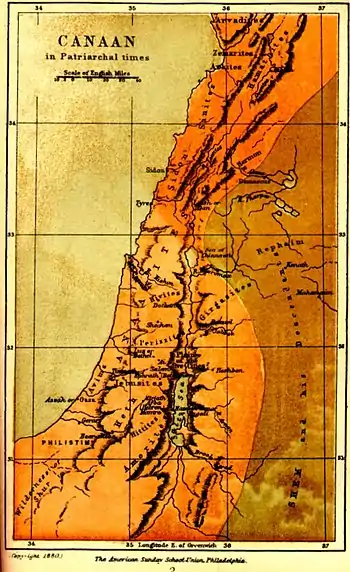

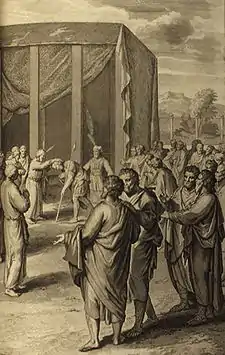

The first reading (עליה, aliyah) tells how, in the 40th year after the Exodus from Egypt, Moses addressed the Israelites on the east side of the Jordan River, recounting the instructions that God had given them.[3] When the Israelites were at Horeb — Mount Sinai — God told them that they had stayed long enough at that mountain, and it was time for them to make their way to the hill country of Canaan and take possession of the land that God swore to assign to their fathers, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and their heirs after them.[4]

Then Moses told the Israelites that he could not bear the burden of their bickering alone, and thus directed them to pick leaders from each tribe who were wise, discerning, and experienced.[5] The first reading ends with Deuteronomy 1:10.[6]

Second reading — Deuteronomy 1:11–21

In the second reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses appointed the leaders as chiefs of thousands, chiefs of hundreds, chiefs of fifties, and chiefs of tens.[7] Moses charged the magistrates to hear and decide disputes justly, treating alike Israelite and stranger, low and high.[8] Moses directed them to bring him any matter that was too difficult to decide.[9]

.jpg.webp)

The Israelites set out from Horeb to Kadesh-barnea, and Moses told them that God had placed the land at their disposal and that they should not fear, but take the land.[10] The second reading ends here.[11]

Third reading — Deuteronomy 1:22–38

In the third reading (עליה, aliyah), the Israelites had asked Moses to send men ahead to scout the land,[12] and he approved the plan, selecting 12 men, one from each tribe.[13] The scouts came to the wadi Eshcol, retrieved some of the fruit of the land, and reported that it was a good land.[14] But the Israelites flouted God's command and refused to go into the land, instead sulking in their tents about reports of people stronger and taller than they and large cities with sky-high walls.[15] Moses told them not to fear, as God would go before them and would fight for them, just as God did in Egypt and the wilderness.[16] When God heard the Israelites' complaint, God became angry and vowed that not one of the men of that evil generation would see the good land that God swore to their fathers, except Caleb, whom God would give the land on which he set foot, because he remained loyal to God.[17] Moses complained that because of the people, God was incensed with Moses too, and told him that he would not enter the land either.[18] God directed that Moses's attendant Joshua would enter the land and allot it to Israel.[19] The third reading ends here.[20]

Fourth reading — Deuteronomy 1:39–2:1

In the fourth reading (עליה, aliyah), God continued that the little ones — whom the Israelites said would be carried off — would also enter and possess the land.[21] The Israelites replied that now they would go up and fight, just as God commanded them, but God told Moses to warn them not to, as God would not travel in their midst and they would be routed by their enemies.[22] Moses told them, but they would not listen, but flouted God's command and willfully marched into the hill country.[23] Then the Amorites who lived in those hills came out like so many bees and crushed the Israelites at Hormah in Seir.[24]

The Israelites remained at Kadesh a long time, marched back into the wilderness by the way of the Sea of Reeds, and then skirted the hill country of Seir a long time.[25] The fourth reading ends here, with the end of the first closed portion (סתומה, setumah).[26]

Fifth reading — Deuteronomy 2:2–30

In the fifth reading (עליה, aliyah), God then told Moses that they had been skirting that hill country long enough and should now turn north.[27] God instructed that the people would be passing through the territory of their kinsmen, the descendants of Esau in Seir, and that the Israelites should be very careful not to provoke them and should purchase what food and water they ate and drank, for God would not give the Israelites any of their land.[28] So the Israelites moved on, away from the descendants of Esau, and marched on in the direction of the wilderness of Moab.[29] The second closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends in the middle of Deuteronomy 2:8.[30]

God told Moses not to harass or provoke the Moabites, for God would not give the Israelites any of their land, having assigned it as a possession to the descendants of Lot.[31] The Israelites spent 38 years traveling from Kadesh-barnea until they crossed the wadi Zered, and the whole generation of warriors perished from the camp, as God had sworn.[32] Deuteronomy 2:16 concludes the third closed portion (סתומה, setumah).[33]

Then God told Moses that the Israelites would be passing close to the Ammonites, but the Israelites should not harass or start a fight with them, for God would not give the Israelites any part of the Ammonites' land, having assigned it as a possession to the descendants of Lot.[34]

.jpg.webp)

God instructed the Israelites to set out across the wadi Arnon, to attack Sihon the Amorite, king of Heshbon, and begin to occupy his land.[35] Moses sent messengers to King Sihon with an offer of peace, asking for passage through his country, promising to keep strictly to the highway, turning neither to the right nor the left, and offering to purchase what food and water they would eat and drink.[36] But King Sihon refused to let the Israelites pass through, because God had stiffened his will and hardened his heart in order to deliver him to the Israelites.[37] The fifth reading ends here, with the end of the fourth closed portion (סתומה, setumah).[38]

Sixth reading — Deuteronomy 2:31–3:14

In the sixth reading (עליה, aliyah), Sihon and his men took the field against the Israelites at Jahaz, but God delivered him to the Israelites, and the Israelites defeated him, captured and doomed all his towns, leaving no survivor, retaining as booty only the cattle and the spoil.[39] From Aroer on the edge of the Arnon valley to Gilead, not a town was too mighty for the Israelites; God delivered everything to them.[40]

The Israelites made their way up the road to Bashan, and King Og of Bashan and his men took the field against them at Edrei, but God told Moses not to fear, as God would deliver Og, his men, and his country to the Israelites to conquer as they had conquered Sihon.[41] So God delivered King Og of Bashan, his men, and his 60 towns into the Israelites' hands, and they left no survivor.[42] Og was so big that his iron bedstead was nine cubits long and four cubits wide.[43]

Moses assigned land to the Reubenites, Gadites, and half-tribe of Manasseh.[44] The sixth reading ends with Deuteronomy 3:14.[45]

Seventh reading — Deuteronomy 3:15–22

In the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses defined the borders of the settlement east of the Jordan, and charged the Reubenites, the Gadites, and the half-tribe of Manasseh that even though they had already received their land, they needed to serve as shock-troops at the head of their Israelite kinsmen, leaving only their wives, children, and livestock in the towns that Moses had assigned to them until God had granted the Israelites their land west of the Jordan.[46]

Moses charged Joshua not to fear the kingdoms west of the Jordan, for God would battle for him and would do to all those kingdoms just as God had done to Sihon and Og.[47] The maftir (מפטיר) reading concludes the parashah with Deuteronomy 3:20–22, and Deuteronomy 3:22 concludes the fifth closed portion (סתומה, setumah).[48]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle read the parashah according to the following schedule:[49]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020, 2023, 2026 . . . | 2021, 2024, 2027 . . . | 2022, 2025, 2028 . . . | |

| Reading | 1:1–2:1 | 2:2–30 | 2:31–3:22 |

| 1 | 1:1–3 | 2:2–5 | 2:31–34 |

| 2 | 1:4–7 | 2:6–12 | 2:35–37 |

| 3 | 1:8–10 | 2:13–16 | 3:1–3 |

| 4 | 1:11–21 | 2:17–19 | 3:4–7 |

| 5 | 1:22–28 | 2:20–22 | 3:8–11 |

| 6 | 1:29–38 | 2:23–25 | 3:12–14 |

| 7 | 1:39–2:1 | 2:26–30 | 3:15–22 |

| Maftir | 1:39–2:1 | 2:28–30 | 3:20–22 |

Ancient parallels

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

Deuteronomy chapter 1

Moshe Weinfeld noted that the instructions by Moses to the magistrates in Deuteronomy 1:16–17 were similar to those given by a 13th century BCE Hittite king to commanders of his border guards. The Hittite king instructed: "If anyone brings a lawsuit . . . the commander shall judge it properly . . . if the case is too big [= difficult] he shall send it to the king. He should not decide it in favor of a superior . . . nobody should take bribes. . . . Do whatever is right."[50]

In Deuteronomy 1:28, the spies reported that the Canaanites were taller than they were. A 13th century BCE Egyptian text told that Bedouin in Canaan were 4 or 5 cubits (6 or 7½ feet) from nose to foot.[51]

Deuteronomy chapter 2

Numbers 13:22 and 28 refer to the "children of Anak" (יְלִדֵי הָעֲנָק, yelidei ha-anak), Numbers 13:33 refers to the "sons of Anak" (בְּנֵי עֲנָק, benei anak), and Deuteronomy 1:28, 2:10–11, 2:21, and 9:2 refer to the "Anakim" (עֲנָקִים). John A. Wilson suggested that the Anakim may be related to the Iy-‘anaq geographic region named in Middle Kingdom Egyptian (19th to 18th century BCE) pottery bowls that had been inscribed with the names of enemies and then shattered as a kind of curse.[52]

Dennis Pardee suggested that the Rephaim cited in Deuteronomy 2:11, 20; 3:11, 13 (as well as Genesis 14:5; 15:20) may be related to a name in a 14th century BCE Ugaritic text.[53]

Inner-Biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[54]

Deuteronomy chapter 1

The Book of Numbers ends in Numbers 36:13 with similar wording to the beginning of Deuteronomy in Deuteronomy 1:1. Numbers 36:13 ends: "These are the commandments and the judgments which the Lord commanded the children of Israel by the hand of Moses in the plains of Moab by the Jordan, across from Jericho." Deuteronomy 1:1 begins: "These are the words which Moses spoke to all Israel on this side of the Jordan in the wilderness, in the plain opposite Suph, between Paran, Tophel, Laban, Hazeroth, and Dizahab." The Pulpit Commentary taught that the wording serves to distinguish the two books: The ending of Numbers indicates that what precedes it is occupied chiefly with what God spoke to Moses, while the beginning of Deuteronomy intimates that what follows is what Moses spoke to the people. This characterizes Deuteronomy as "emphatically a book for the people."[55]

Exodus 18:13–26 and Deuteronomy 1:9–18 both tell the story of appointment of judges. Whereas in Deuteronomy 1:9–18, Moses implies that he decided to distribute his duties, Exodus 18:13–24 makes clear that Jethro suggested the idea to Moses and persuaded him of its merit. And Numbers 11:14–17 and Deuteronomy 1:9–12 both report the burden on Moses of leading the people. Whereas in Deuteronomy 1:15, the solution is heads of tribes, thousands, hundreds, fifties, and tens, in Numbers 11:16, the solution is 70 elders.

In Deuteronomy 1:10, Moses reported that God had multiplied the Israelites until they were then as numerous as the stars. In Genesis 15:5, God promised that Abraham’s descendants would as numerous as the stars of heaven. Similarly, in Genesis 22:17, God promised that Abraham’s descendants would as numerous as the stars of heaven and the sands on the seashore. In Genesis 26:4, God reminded Isaac that God had promised Abraham that God would make his heirs as numerous as the stars. In Genesis 32:13, Jacob reminded God that God had promised that Jacob’s descendants would be as numerous as the sands. In Exodus 32:13, Moses reminded God that God had promised to make the Patriarch’s descendants as numerous as the stars. In Deuteronomy 10:22, Moses reported that God had made the Israelites as numerous as the stars. And Deuteronomy 28:62 foretold that the Israelites would be reduced in number after having been as numerous as the stars.

Numbers 13:1–14:45 and Deuteronomy 1:19–45 both tell the story of the Twelve Spies. Whereas Numbers 13:1–2 says that God told Moses to send men to spy out the land of Canaan, in Deuteronomy 1:22–23, Moses recounted that all the Israelites asked him to send men to search the land, and the idea pleased him. Whereas Numbers 13:31–33 reports that the spies spread an evil report that the Israelites were not able to go up against the people of the land for they were stronger and taller than the Israelites, in Deuteronomy 1:25, Moses recalled that the spies brought back word that the land that God gave them was good.

Professor Patrick D. Miller, formerly of Princeton Theological Seminary, saw the reassurance of Deuteronomy 1:29–30 echoed in Genesis 15:1–5 and 26:24 and Isaiah 41:8–16; 43:1–7; and 44:1–5.[56]

Deuteronomy chapter 2

Numbers 20:14–21, Deuteronomy 2:4–11 and Judges 11:17 each report the Israelites' interaction with Edom and Moab. Numbers 20:14–21 and Judges 11:17 report that the Israelites sent messengers to the kings of both countries asking for passage through their lands, and according to the passage in Numbers the Israelites offered to trade with Edom, but both kings declined to let the Israelites pass. Deuteronomy 2:6 reports that the Israelites were instructed to pay Edom for food and drink.

Deuteronomy chapter 3

The blessing of Moses for Gad in Deuteronomy 33:20–21 relates to the role of Gad in taking land east of the Jordan in Numbers 32:1–36 and Deuteronomy 3:16–20. In Deuteronomy 33:20, Moses commended Gad's fierceness, saying that Gad dwelt as a lioness and tore the arm and the head. Immediately thereafter, in Deuteronomy 33:21, Moses noted that Gad chose a first part of the land for himself.

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[57]

Deuteronomy chapter 1

The Mishnah taught that when fulfilling the commandment of Deuteronomy 31:12 to "assemble the people . . . that they may hear . . . all the words of this law," the king would start reading at Deuteronomy 1:1.[58]

The Tosefta read the words of Deuteronomy 1:1, “These are the words . . . ,” to teach that all these words — the words of the written Torah and the words of the Oral Torah — were given by God so that the one should open the chambers of one’s heart and allow into it the words of both the House of Shammai and the House of Hillel, the words of those who declare unclean and the words of those who declare clean. Thus even if some words of Torah may appear contradictory, one should still learn Torah to try to understand God’s will.[59]

The Avot of Rabbi Natan read the listing of places in Deuteronomy 1:1 to allude to how God tested the Israelites with ten trials in the Wilderness, and they failed them all. The words "In the wilderness" alludes to the Golden Calf, as Exodus 32:8}HE reports. "On the plain" alludes to how they complained about not having water, as Exodus 17:3 reports. "Facing Suf" alludes to how they rebelled at the Sea of Reeds (or some say to the idol that Micah made). Rabbi Judah cited Psalms 106:7, "They rebelled at the Sea of Reeds." "Between Paran" alludes to the Twelve Spies, as Numbers 13:3 says, "Moses sent them from the wilderness of Paran." "And Tophel" alludes to the frivolous words (תפלות, tiphlot) they said about the manna. "Lavan" alludes to Koraḥ's mutiny. "Ḥatzerot" alludes to the quails. And in Deuteronomy 9:22, it says, "At Tav'erah, and at Masah, and at Kivrot HaTa'avah." And "Di-zahav" alludes to when Aaron said to them: "Enough (דַּי, dai) of this golden (זָהָב, zahav) sin that you have committed with the Calf!" But Rabbi Eliezer ben Ya'akov said it means "Terrible enough (דַּי, dai) is this sin that Israel was punished to last from now until the resurrection of the dead."[60]

Similarly, the school of Rabbi Yannai interpreted the place name Di-zahab (דִי זָהָב) in Deuteronomy 1:1 to refer to one of the Israelites' sins that Moses recounted in the opening of his address. The school of Rabbi Yannai deduced from the word Di-zahab that Moses spoke insolently towards heaven. The school of Rabbi Yannai taught that Moses told God that it was because of the silver and gold (זָהָב, zahav) that God showered on the Israelites until they said "Enough" (דַּי, dai) that the Israelites made the Golden Calf. They said in the school of Rabbi Yannai that a lion does not roar with excitement over a basket of straw but over a basket of meat. Rabbi Oshaia likened it to the case of a man who had a lean but large-limbed cow. The man gave the cow good feed to eat and the cow started kicking him. The man deduced that it was feeding the cow good feed that caused the cow to kick him. Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba likened it to the case of a man who had a son and bathed him, anointed him, gave him plenty to eat and drink, hung a purse round his neck, and set him down at the door of a brothel. How could the boy help sinning? Rav Aha the son of Rav Huna said in the name of Rav Sheshet that this bears out the popular saying that a full stomach leads to a bad impulse. As Hosea 13:6 says, "When they were fed they became full, they were filled and their heart was exalted; therefore they have forgotten Me."[61]

The Sifre read Deuteronomy 1:3–4 to indicate that Moses spoke to the Israelites in rebuke. The Sifre taught that Moses rebuked them only when he approached death, and the Sifre taught that Moses learned this lesson from Jacob, who admonished his sons in Genesis 49 only when he neared death. The Sifre cited four reasons why people do not admonish others until the admonisher nears death: (1) so that the admonisher does not have to repeat the admonition, (2) so that the one rebuked would not suffer undue shame from being seen again, (3) so that the one rebuked would not bear ill will to the admonisher, and (4) so that the one may depart from the other in peace, for admonition brings peace. The Sifre cited as further examples of admonition near death: (1) when Abraham reproved Abimelech in Genesis 21:25, (2) when Isaac reproved Abimelech, Ahuzzath, and Phicol in Genesis 26:27, (3) when Joshua admonished the Israelites in Joshua 24:15, (4) when Samuel admonished the Israelites in 1 Samuel 12:34–35, and (5) when David admonished Solomon in 1 Kings 2:1.[62]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer identified Og, king of Bashan, mentioned in Deuteronomy 1:4 and 3:1–13, with Abraham’s servant Eliezer introduced in Genesis 15:2 and with the unnamed steward of Abraham’s household in Genesis 24:2. The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told that when Abraham left Ur of the Chaldees, all the magnates of the kingdom gave him gifts, and Nimrod gave Abraham Nimrod’s first-born son Eliezer as a perpetual slave. After Eliezer had dealt kindly with Isaac by securing Rebekah to be Isaac’s wife, he set Eliezer free, and God gave Eliezer his reward in this world by raising him up to become a king — Og, king of Bashan.[63]

Reading Deuteronomy 1:5, "Beyond the Jordan, in the land of Moab, Moses took upon himself to expound (בֵּאֵר, be’er) this law," the Gemara noted the use of the same word as in Deuteronomy 27:8 with regard to the commandment to erect the stones on Mount Ebal, "And you shall write on the stones all the words of this law clearly elucidated (בַּאֵר, ba’er)." The Gemara reasoned through a verbal analogy that Moses also wrote down the Torah on stones in the land of Moab and erected them there. The Gemara concluded that there were thus three sets of stones so inscribed.[64]

A Midrash taught that Deuteronomy 1:7, Genesis 15:18, and Joshua 1:4 call the Euphrates "the Great River" because it encompasses the Land of Israel. The Midrash noted that at the creation of the world, the Euphrates was not designated "great." But it is called "great" because it encompasses the Land of Israel, which Deuteronomy 4:7 calls a "great nation." As a popular saying said, the king's servant is a king, and thus Scripture calls the Euphrates great because of its association with the great nation of Israel.[65]

The Tosefta taught that just as the Israelites were commanded to establish courts of justice in their towns (as Moses reported in Deuteronomy 1:9–18) all children of Noah (that is, all people) were admonished (as the first of seven Noahide laws) to set up courts of justice.[66]

Rabbi Meir taught that when, as Exodus 39:43 reports, Moses saw all the work of the Tabernacle and the Priestly garments that the Israelites had done, “Moses blessed them” with the blessing of Deuteronomy 1:11, saying, “The Lord, the God of your ancestors, make you a thousand times so many more as you are, and bless you, as God has promised you!”[67]

Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani, citing Rabbi Johanan, noted that in Deuteronomy 1:13, God told Moses, "Get you from each one of your tribes, wise men and understanding, and full of knowledge," but in Deuteronomy 1:15, Moses reported, "So I took the heads of your tribes, wise men and full of knowledge." Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani thus concluded that Moses could not find men of "understanding" in his generation. In contrast, Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani noted that 1 Chronicles 12:33 reports that "the children of Issachar . . . had understanding." Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani noted that Genesis 30:27 reports that Jacob and Leah conceived Issachar after "Leah went out to meet him, and said: ‘You must come to me, for I have surely hired you.'" Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani thus concluded that a woman who solicits her husband to perform the marital obligation, as Leah did, will have children the like of whom did not exist even in the generation of Moses.[68]

Rabbi Berekiah taught in the name of Rabbi Hanina that judges must possess seven qualities, and Deuteronomy 1:13 mentions three: They must be "wise men, and understanding, and full of knowledge." And Exodus 18:21 enumerates the other four: "Moreover you shall provide out of all the people able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating unjust gain." Scripture does not state all seven qualities together to teach that if people possessing all the seven qualities are not available, then those possessing four are selected; if people possessing four qualities are not available, then those possessing three are selected; and if even these are not available, then those possessing one quality are selected, for as Proverbs 31:10 says, "A woman of valor who can find?"[69]

Arius asked Rabbi Jose what the difference is between "wise" and "discerning" in Deuteronomy 1:13. Rabbi Jose answered that a wise person is like a rich money-changer. When people bring coins to evaluate, the rich money-changer evaluates them, and if people do not bring coins to evaluate, the rich money-changer seeks out coins to evaluate. A discerning person is like a poor money-changer. When people bring coins to evaluate, the poor money-changer evaluates them, but if people do not bring coins to evaluate, the poor money-changer sits and daydreams.[70]

The Sifre read the words "well-known to your tribes" in Deuteronomy 1:13 to refer to men who were known to the people. The Sifre taught that Moses told the people that if a candidate were wrapped in a cloak and took a seat before Moses, he might not know from which tribe the candidate came (or whether he was fit for the job). But the people would know him, for they grew up with him.[70]

Rav Hisda taught that at first, officers were appointed only from the Levites, for 2 Chronicles 19:11 says, "And the officers of the Levites before you," but in Rav Hisda's time, officers were appointed only from the Israelites, for it was said (paraphrasing Deuteronomy 1:13), "And officers over you shall come from the majority" (that is, the Israelites).[71]

Interpreting Deuteronomy 1:15, the Rabbis taught in a Baraita that since the nation numbered about 600,000 men, the chiefs of thousands amounted to 600; those of hundreds, 6,000; those of fifties, 12,000; and those of tens, 60,000. Hence they taught that the number of officers in Israel totaled 78,600.[72]

Rabbi Johanan interpreted the words "And I charged your judges at that time" in Deuteronomy 1:16 to teach that judges were to resort to the rod and the lash with caution. Rabbi Haninah interpreted the words "hear the causes between your brethren, and judge righteously" in Deuteronomy 1:16 to warn judges not to listen to the claims of litigants in the absence of their opponents, and to warn litigants not to argue their cases to the judge before their opponents have appeared. Resh Lakish interpreted the words "judge righteously" in Deuteronomy 1:16 to teach judges to consider all the aspects of the case before deciding. Rabbi Judah interpreted the words "between your brethren" in Deuteronomy 1:16 to teach judges to make a scrupulous division of liability between the lower and the upper parts of a house, and Rabbi Judah interpreted the words "and the stranger that is with him" in Deuteronomy 1:16 to teach judges to make a scrupulous division of liability even between a stove and an oven.[73]

Rabbi Eliezer the Great taught that the Torah warns against wronging a stranger in 36, or others say 46, places (including Deuteronomy 1:16).[74] The Gemara went on to cite Rabbi Nathan's interpretation of Exodus 22:20, "You shall neither wrong a stranger, nor oppress him; for you were strangers in the land of Egypt," to teach that one must not taunt one's neighbor about a flaw that one has oneself. The Gemara taught that thus a proverb says: If there is a case of hanging in a person's family history, do not say to the person, "Hang up this fish for me."[75]

Rabbi Judah interpreted the words "you shall not respect persons in judgment" in Deuteronomy 1:17 to teach judges not to favor their friends, and Rabbi Eleazar interpreted the words to teach judges not to treat a litigant as a stranger, even if the litigant was the judge's enemy.[76]

Resh Lakish interpreted the words "you shall hear the small and the great alike" in Deuteronomy 1:17 to teach that a judge must treat a lawsuit involving the smallest coin in circulation ("a mere perutah") as of the same importance as one involving 2 million times the value ("a hundred mina"). And the Gemara deduced from this rule that a judge must hear cases in the order that they were brought, even if a case involving a lesser value was brought first.[77]

Rabbi Hanan read the words "you shall not be afraid of . . . any man" in Deuteronomy 1:17 to teach judges not to withhold any arguments out of deference to the powerful.[77]

Resh Lakish (or others say Rabbi Judah ben Lakish or Rabbi Joshua ben Lakish) read the words "you shall not be afraid of the face of any man" in Deuteronomy 1:17 to teach that once a judge has heard a case and knows in whose favor judgment inclines, the judge cannot withdraw from the case, even if the judge must rule against the more powerful litigant. But before a judge has heard a case, or even after so long as the judge does not yet know in whose favor judgment inclines, the judge may withdraw from the case to avoid having to rule against the more powerful litigant and suffer harassment from that litigant.[78]

Rabbi Eliezer the son of Rabbi Jose the Galilean deduced from the words "the judgment is God's" in Deuteronomy 1:17 that once litigants have brought a case to court, a judge must not arbitrate a settlement, for a judge who arbitrates sins by deviating from the requirements of God's Torah; rather, the judge must "let the law cut through the mountain" (and thus even the most difficult case).[79]

Rabbi Hama son of Rabbi Haninah read the words "the judgment is God's" in Deuteronomy 1:17 to teach that God views the action of wicked judges unjustly taking money away from one and giving it to another as an imposition upon God, putting God to the trouble of returning the value to the rightful owner. (Rashi interpreted that it was as though the judge had taken the money from God.)[80]

Rabbi Haninah (or some say Rabbi Josiah) taught that Moses was punished for his arrogance when he told the judges in Deuteronomy 1:17: "the cause that is too hard for you, you shall bring to me, and I will hear it." Rabbi Haninah said that Numbers 27:5 reports Moses's punishment, when Moses found himself unable to decide the case of the daughters of Zelophehad. Rav Nahman objected to Rabbi Haninah's interpretation, noting that Moses did not say that he would always have the answers, but merely that he would rule if he knew the answer or seek instruction if he did not. Rav Nahman cited a Baraita to explain the case of the daughters of Zelophehad: God had intended that Moses write the laws of inheritance, but found the daughters of Zelophehad worthy to have the section recorded on their account.[80]

Rabbi Eleazar, on the authority of Rabbi Simlai, noted that Deuteronomy 1:16 says, "And I charged your judges at that time," while Deuteronomy 1:18 similarly says, "I charged you [the Israelites] at that time." Rabbi Eleazar deduced that Deuteronomy 1:18 meant to warn the Congregation to revere their judges, and Deuteronomy 1:16 meant to warn the judges to be patient with the Congregation. Rabbi Hanan (or some say Rabbi Shabatai) said that this meant that judges must be as patient as Moses, who Numbers 11:12 reports acted "as the nursing father carries the sucking child."[81]

A Baraita taught that when hedonists multiplied, justice became perverted, conduct deteriorated, and God found no satisfaction in the world. When those who displayed partiality in judgment multiplied, the command of Deuteronomy 1:17, "You shall not be afraid of the face of any man," was discontinued; and the command of Deuteronomy 1:17, "You shall not respect persons in judgment," ceased to be practiced; and people threw off the yoke of Heaven and placed upon themselves the yoke of human beings. When those who whispered to judges (to influence the judges in favor of one party) multiplied, the fierceness of Divine anger increased against Israel, and the Divine Presence (Shechinah) departed, because, as Psalm 82:1 teaches, "He judges among the judges" (that is, God abides only with honest judges). When there multiplied people of whom Ezekiel 33:31 says, "Their heart goes after their gain," there multiplied people who (in the words of Isaiah 5:20) "call evil good, and good evil." When there multiplied people who "call evil good, and good evil," woes increased in the world.[82]

Resh Lakish interpreted the words "Send you" in Numbers 13:2 to indicate that God gave Moses discretion whether or not to send the spies. Resh Lakish read Moses' recollection of the matter in Deuteronomy 1:23 that "the thing pleased me well" to mean that sending the spies pleased Moses well but not God.[83]

Rabbi Ammi cited the spies' statement in Deuteronomy 1:28 that the Canaanite cities were "great and fortified up to heaven" to show that the Torah sometimes exaggerated.[84]

Reading the words, "And how I bore you on eagles' wings," in Exodus 19:4, the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael taught that eagles differ from all other birds because other birds carry their young between their feet, being afraid of other birds flying higher above them. Eagles, however, fear only people who might shoot arrows at them from below. Eagles, therefore, prefer that the arrows hit them rather than their children. The Mekhilta compared this to a man who walked on the road with his son in front of him. If robbers, who might seek to capture his son, come from in front, the man puts his son behind him. If a wolf comes from behind, the man puts his son in front of him. If robbers come from in front and wolves from behind, the man puts his son on his shoulders. As Deuteronomy 1:31 says, "You have seen how the Lord your God bore you, as a man bears his son."[85]

.jpg.webp)

The Mishnah taught that it was on Tisha B'Av (just before which Jews read parashah Devarim) that God issued the decree reported in Deuteronomy 1:35–36 that the generation of the spies would not enter the Promised Land.[86]

Noting that in the incident of the spies, God did not punish those below the age of 20 (see Numbers 14:29), whom Deuteronomy 1:39 described as "children that . . . have no knowledge of good or evil," Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani taught in Rabbi Jonathan's name that God does not punish people for the actions that they take in their first 20 years.[87]

Deuteronomy chapter 2

Interpreting the words "You have circled this mountain (הָר, har) long enough" in Deuteronomy 2:3, Rabbi Haninah taught that Esau paid great attention to his parent (horo), his father, whom he supplied with meals, as Genesis 25:28 reports, "Isaac loved Esau, because he ate of his venison." Rabbi Samuel the son of Rabbi Gedaliah concluded that God decided to reward Esau for this. When Jacob offered Esau gifts, Esau answered Jacob in Genesis 33:9, "I have enough (רָב, rav); do not trouble yourself." So God declared that with the same expression that Esau thus paid respect to Jacob, God would command Jacob's descendants not to trouble Esau's descendants, and thus God told the Israelites, "You have circled . . . long enough (רַב, rav)."[88]

Rav Hiyya bar Abin said in Rabbi Johanan's name that the words, "I have given Mount Seir to Esau for an inheritance," in Deuteronomy 2:5 establish that even idolaters inherit from their parents under Biblical law. The Gemara reported a challenge that perhaps Esau inherited because he was an apostate Jew. Rav Hiyya bar Abin thus argued that the words, "I have given Ar to the children of Lot as a heritage," in Deuteronomy 2:9 establish gentiles' right to inherit.[89]

Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba, citing Rabbi Johanan, taught that God rewards even polite speech. In Genesis 19:37, Lot's older daughter named her son Moab ("of my father"), and so in Deuteronomy 2:9, God told Moses, "Be not at enmity with Moab, neither contend with them in battle"; God forbade only war with the Moabites, but the Israelites might harass them. In Genesis 19:38, in contrast, Lot's younger daughter named her son Ben-Ammi (the less shameful "son of my people"), and so in Deuteronomy 2:19, God told Moses, "Harass them not, nor contend with them"; the Israelites were not to harass the Ammonites at all.[90]

.jpg.webp)

Reading Deuteronomy 2:9, "And the Lord spoke to me, ‘Distress not the Moabites, neither contend with them in battle,'" Ulla argued that it certainly could not have entered the mind of Moses to wage war without God's authorization. So we must deduce that Moses on his own reasoned that if in the case of the Midianites who came only to assist the Moabites (in Numbers 22:4), God commanded (in Numbers 25:17), "Vex the Midianites and smite them," in the case of the Moabites themselves, the same injunction should apply even more strongly. But God told Moses that the idea that Moses had in his mind was not the idea that God had in God's mind. For God was to bring two doves forth from the Moabites and the Ammonites — Ruth the Moabitess and Naamah the Ammonitess.[91]

Even though in Deuteronomy 2:9 and 2:19, God forbade the Israelites from occupying the territory of Ammon and Moab, Rav Papa taught that the land of Ammon and Moab that Sihon conquered (as reported in Numbers 21:26) became purified for acquisition by the Israelites through Sihon's occupation of it (as discussed in Judges 11:13–23).[92]

Explaining why Rabban Simeon ben Gamaliel said[93] that there never were in Israel more joyous days than Tu B'Av (the fifteenth of Av) and Yom Kippur, Rabbah bar bar Hanah said in the name of Rabbi Johanan (or others say Rav Dimi bar Joseph said in the name of Rav Nahman) that Tu B'Av was the day on which the generation of the wilderness stopped dying out. For a Master deduced from the words, "So it came to pass, when all the men of war were consumed and dead . . . that the Lord spoke to me," in Deuteronomy 2:16–17 that as long as the generation of the wilderness continued to die out, God did not communicate with Moses, and only thereafter — on Tu B'Av — did God resume that communication.[94] Thus God's address to Moses in Numbers 20:6–8 (in which he instructed Moses to speak to the rock to bring forth water) may have been the first time that God had spoken to Moses in 38 years.[95]

Citing Deuteronomy 2:24 and 26, Rabbi Joshua of Siknin said in the name of Rabbi Levi that God agreed to whatever Moses decided. For in Deuteronomy 2:24, God commanded Moses to make war on Sihon, but Moses did not do so, but as Deuteronomy 2:26 reports, Moses instead “sent messengers.” God told Moses that even though God had commanded Moses to make war with Sihon and instead Moses began with peace, God would confirm Moses’ decision and decree that in every war upon which Israel entered, Israel must begin with an offer of peace, as Deuteronomy 20:10 says, “When you draw near to a city to fight against it, then proclaim peace to it.”[96]

A Baraita deduced from Deuteronomy 2:25 that just as the sun stood still for Joshua in Joshua 10:13, so the sun stood still for Moses, as well. The Gemara (or some say Rabbi Eleazar) explained that the identical circumstances could be derived from the use of the identical expression "I will begin" in Deuteronomy 2:25 and in Joshua 3:7. Rabbi Johanan (or some say Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani) taught that this conclusion could be derived from the use of the identical word "put" (tet) in Deuteronomy 2:25 and Joshua 10:11. And Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani (or some say Rabbi Johanan) taught that this conclusion could be deduced from the words "the peoples that are under the whole heaven, who, when they hear the report of you, shall tremble, and be in anguish because of you" in Deuteronomy 2:25. Rabbi Samuel (or some say Rabbi Johanan) taught that the peoples trembled and were in anguish because of Moses when the sun stood still for him.[97]

A Midrash interpreted the Israelites' encounter with Sihon in Numbers 21:21–31 and Deuteronomy 2:24–3:10. Noting the report of Numbers 21:21–22 that "Israel sent messengers to Sihon king of the Amorites, saying: ‘Let me pass through your land,'" the Midrash taught that the Israelites sent messengers to Sihon just as they had to Edom to inform the Edomites that the Israelites would not cause Edom any damage. Noting the report of Deuteronomy 2:28 that the Israelites offered Sihon, "You shall sell me food for money . . . and give me water for money," the Midrash noted that water is generally given away for free, but the Israelites offered to pay for it. The Midrash noted that in Numbers 21:21, the Israelites offered, "We will go by the king's highway," but in Deuteronomy 2:29, the Israelites admitted that they would go "until [they] shall pass over the Jordan," thus admitting that they were going to conquer Canaan. The Midrash compared the matter to a watchman who received wages to watch a vineyard, and to whom a visitor came and asked the watchman to go away so that the visitor could cut off the grapes from the vineyard. The watchman replied that the sole reason that the watchman stood guard was because of the visitor. The Midrash explained that the same was true of Sihon, as all the kings of Canaan paid Sihon money from their taxes, since Sihon appointed them as kings. The Midrash interpreted Psalm 135:11, which says, "Sihon king of the Amorites, and Og king of Bashan, and all the kingdoms of Canaan," to teach that Sihon and Og were the equal of all the other kings of Canaan. So the Israelites asked Sihon to let them pass through Sihon's land to conquer the kings of Canaan, and Sihon replied that the sole reason that he was there was to protect the kings of Canaan from the Israelites. Interpreting the words of Numbers 21:23, "and Sihon would not suffer Israel to pass through his border; but Sihon gathered all his people together," the Midrash taught that God brought this about designedly so as to deliver Sihon into the Israelites' hands without trouble. The Midrash interpreted the words of Deuteronomy 3:2, "Sihon king of the Amorites, who dwelt at Heshbon," to say that if Heshbon had been full of mosquitoes, no person could have conquered it, and if Sihon had been living in a plain, no person could have prevailed over him. The Midrash taught that Sihon thus would have been invincible, as he was powerful and dwelt in a fortified city. Interpreting the words, "Who dwelt at Heshbon," the Midrash taught that had Sihon and his armies remained in different towns, the Israelites would have worn themselves out conquering them all. But God assembled them in one place to deliver them into the Israelites' hands without trouble. In the same vein, in Deuteronomy 2:31 God said, "Behold, I have begun to deliver up Sihon . . . before you," and Numbers 21:23 says, "Sihon gathered all his people together," and Numbers 21:23 reports, "And Israel took all these cities."[98]

Deuteronomy chapter 3

A Midrash taught that according to some authorities, Israel fought Sihon in the month of Elul, celebrated the Festival in Tishri, and after the Festival fought Og. The Midrash inferred this from the similarity of the expression in Deuteronomy 16:7, "And you shall turn in the morning, and go to your tents," which speaks of an act that was to follow the celebration of a Festival, and the expression in Numbers 21:3, "and Og the king of Bashan went out against them, he and all his people." The Midrash inferred that God assembled the Amorites to deliver them into the Israelites' hands, as Numbers 21:34 says, "and the Lord said to Moses: ‘Fear him not; for I have delivered him into your hand." The Midrash taught that Moses was afraid, as he thought that perhaps the Israelites had committed a trespass in the war against Sihon, or had soiled themselves by the commission of some transgression. God reassured Moses that he need not fear, for the Israelites had shown themselves perfectly righteous. The Midrash taught that there was not a mighty man in the world more difficult to overcome than Og, as Deuteronomy 3:11 says, "only Og king of Bashan remained of the remnant of the Rephaim." The Midrash told that Og had been the only survivor of the strong men whom Amraphel and his colleagues had slain, as may be inferred from Genesis 14:5, which reports that Amraphel "smote the Rephaim in Ashteroth-karnaim," and one may read Deuteronomy 3:1 to indicate that Og lived near Ashteroth. The Midrash taught that Og was the refuse among the Rephaim, like a hard olive that escapes being mashed in the olive press. The Midrash inferred this from Genesis 14:13, which reports that "there came one who had escaped, and told Abram the Hebrew," and the Midrash identified the man who had escaped as Og, as Deuteronomy 3:11 describes him as a remnant, saying, "only Og king of Bashan remained of the remnant of the Rephaim." The Midrash taught that Og intended that Abram should go out and be killed. God rewarded Og for delivering the message by allowing him to live all the years from Abraham to Moses, but God collected Og's debt to God for his evil intention toward Abraham by causing Og to fall by the hand of Abraham's descendants. On coming to make war with Og, Moses was afraid, thinking that he was only 120 years old, while Og was more than 500 years old, and if Og had not possessed some merit, he would not have lived all those years. So God told Moses (in the words of Numbers 21:34), "fear him not; for I have delivered him into your land," implying that Moses should slay Og with his own hand. The Midrash noted that in Deuteronomy 3:2, God told Moses to "do to him as you did to Sihon," and Deuteronomy 3:6 reports that the Israelites "utterly destroyed them," but Deuteronomy 3:7 reports, "All the cattle, and the spoil of the cities, we took for a prey to ourselves." The Midrash concluded that the Israelites utterly destroyed the people so as not to derive any benefit from them.[99]

Rabbi Phinehas ben Yair taught that the 60 rams, 60 goats, and 60 lambs that Numbers 7:88 reports that the Israelites sacrificed as a dedication-offering of the altar symbolized (among other things) the 60 cities of the region of Argob that Deuteronomy 3:4 reports that the Israelites conquered.[100]

Abba Saul (or some say Rabbi Johanan) told that once when pursuing a deer, he entered a giant thighbone of a corpse and pursued the deer for three parasangs but reached neither the deer nor the end of the thighbone. When he returned, he was told that it was the thighbone of Og, King of Bashan, of whose extraordinary height Deuteronomy 3:11 reports.[101]

A Midrash deduced from the words in Deuteronomy 3:11, "only Og king of Bashan remained . . . behold, his bedstead . . . is it not in Rabbah of the children of Ammon?" that Og had taken all the land of the children of Ammon. Thus there was no injustice when Israel came and took the land away from Og.[102]

Noting that Deuteronomy 3:21 and 3:23 both use the same expression "at that time" (בָּעֵת הַהִוא, ba'eit ha-hiv), a Midrash deduced that the events of the two verses took place at the same time. Thus Rav Huna taught that as soon as God told Moses to hand over his office to Joshua, Moses immediately began to pray to be permitted to enter the Promised Land. The Midrash compared Moses to a governor who could be sure that the king would confirm whatever orders he gave so long as he retained his office. The governor redeemed whomever he desired and imprisoned whomever he desired. But as soon as the governor retired and another was appointed in his place, the gatekeeper would not let him enter the king's palace. Similarly, as long as Moses remained in office, he imprisoned whomever he desired and released whomever he desired, but when he was relieved of his office and Joshua was appointed in his stead, and he asked to be permitted to enter the Promised Land, God in Deuteronomy 3:26 denied his request.[103]

Rabbi Samuel bar Nahman taught that Moses first incurred his fate to die in the wilderness, about which God told him in Deuteronomy 3:27, from his conduct at the Burning Bush, for there God tried for seven days to persuade Moses to go on his errand to Egypt, as Exodus 4:10 says, “And Moses said to the Lord: ‘Oh Lord, I am not a man of words, neither yesterday, nor the day before, nor since you have spoken to your servant’” (which the Midrash interpreted to indicate seven days of conversation). And in the end, Moses told God in Exodus 4:13, “Send, I pray, by the hand of him whom You will send.” God replied that God would keep this in store for Moses. Rabbi Berekiah in Rabbi Levi's name and Rabbi Helbo give different answers on when God repaid Moses. One said that all the seven days of the consecration of the priesthood in Leviticus 8, Moses functioned as High Priest, and he came to think that the office belonged to him. But in the end, God told Moses that the job was not his, but his brother’s, as Leviticus 9:1 says, “And it came to pass on the eighth day, that Moses called Aaron.” The other taught that all the first seven days of Adar of the fortieth year, Moses beseeched God to enter the Promised Land, but in the end, God told him in Deuteronomy 3:27, “You shall not go over this Jordan.”[104]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[105]

Deuteronomy chapter 1

In the Zohar, Rabbi Jose expounded on Exodus 35:10: "And let every wise-hearted man among you come and make all that the Lord has commanded." Rabbi Jose taught that when God told Moses in Deuteronomy 1:13, "Get you wise men and men of discernment," Moses searched all of Israel but did not find men of discernment, and so in Deuteronomy 1:15, Moses said, "So I took the heads of your tribes, wise men, and full of knowledge," without mentioning men of discernment. Rabbi Jose deduced that the man of discernment (navan) is of a higher degree than the wise man (hacham), for even a pupil who gives new ideas to a teacher is called "wise." A wise man knows for himself as much as is required, but the man of discernment apprehends the whole, knowing both his own point of view and that of others. Exodus 35:10 uses the term "wise-hearted" because the heart was seen to be the seat of wisdom. Rabbi Jose taught that the man of discernment apprehends the lower world and the upper world, his own being and the being of others.[106]

Interpreting Deuteronomy 1:13 together with Exodus 18:21, Maimonides taught that judges must be on the highest level of righteousness. An effort should be made that they be white-haired, of impressive height, of dignified appearance, and people who understand whispered matters and who understand many different languages so that the court will not need to hear testimony from an interpreter.[107] Maimonides taught that one need not demand that a judge for a court of three possess all these qualities, but a judge must, however, possess seven attributes: wisdom, humility, fear of God, loathing for money, love for truth, being beloved by people at large, and a good reputation. Maimonides cited Deuteronomy 1:13, “Men of wisdom and understanding,” for the requirement of wisdom. Deuteronomy 1:13 continues, “Beloved by your tribes,” which Maimonides read to refer to those who are appreciated by people at large. Maimonides taught that what will make them beloved by people is conducting themselves with a favorable eye and a humble spirit, being good company, and speaking and conducting their business with people gently. Maimonides read Exodus 18:21, “men of power,” to refer to people who are mighty in their observance of the commandments, who are very demanding of themselves, and who overcome their evil inclination until they possess no unfavorable qualities, no trace of an unpleasant reputation, even during their early adulthood, they were spoken of highly. Maimonides read Exodus 18:21, “men of power,” also to imply that they should have a courageous heart to save the oppressed from the oppressor, as Exodus 2:17 reports, “And Moses arose and delivered them.” Maimonides taught that just as Moses was humble, so, too, every judge should be humble. Exodus 18:21 continues “God-fearing,” which is clear. Exodus 18:21 mentions “men who hate profit,” which Maimonides took to refer to people who do not become overly concerned even about their own money; they do not pursue the accumulation of money, for anyone who is overly concerned about wealth will ultimately be overcome by want. Exodus 18:21 continues “men of truth,” which Maimonides took to refer to people who pursue justice because of their own inclination; they love truth, hate crime, and flee from all forms of crookedness.[108]

Deuteronomy chapter 2

Reading God’s instruction in Deuteronomy 2:6 that the Israelites should buy food, Abraham ibn Ezra commented that this would be only if the Edomites wanted to sell. Ibn Ezra noted that some view Deuteronomy 2:6 as asking a question, for Israel had no need for food and drink (having had manna daily).[109]

Even though in Deuteronomy 2:24, God told Moses to "begin to possess" the land of Sihon, nonetheless in Deuteronomy 2:26, Moses "sent messengers . . . to Sihon." Rashi explained that even though God had not commanded Moses to call to Sihon in peace, Moses learned to do so from what God did when God first was about to give the Torah to Israel. God first took the Torah to Esau and Ishmael, although it was clear to God that they would not accept it, because God wished to begin with them in peace.[110] Nachmanides disagreed, concluding that Moses sent messengers to Sihon before God instructed Moses to go to war with Sihon.[111]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Deuteronomy chapter 1

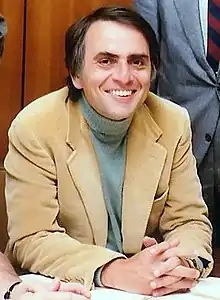

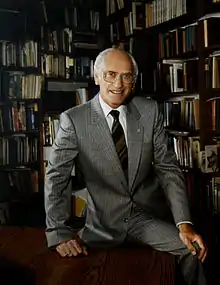

In Deuteronomy 1:10, Moses reported that God had multiplied the Israelites until they were then as numerous as the stars. In Genesis 15:5, God promised that Abraham’s descendants would be as numerous as the stars of heaven. And in Genesis 22:17, God promised that Abraham’s descendants would be as numerous as the stars of heaven and the sands on the seashore. The astronomer Carl Sagan reported that there are more stars in the universe than sands on all the beaches on the Earth.[112]

The 20th century Reform Rabbi Gunther Plaut observed that in Deuteronomy 1:13, the people — not Moses, as recorded in Exodus 18:21 and 24–25 — chose the officials who would share the tasks of leadership and dispute resolution.[113] Jeffrey Tigay, Professor Emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania, however, reasoned that although Moses selected the appointees as recorded in Exodus 18:21 and 24–25, he could not have acted without recommendations by the people, for the officers would have numbered in the thousands (according to the Talmud, 78,600), and Moses could not have known that many qualified people, especially as he had not lived among the Israelites before the Exodus.[114] Professor Robert Alter of the University of California, Berkeley, noted several differences between the accounts in Deuteronomy 1 and Exodus 18, all of which he argued reflected the distinctive aims of Deuteronomy. Jethro conceives the scheme in Exodus 18, but is not mentioned in Deuteronomy 1, and instead, the plan is entirely Moses's idea, as Deuteronomy is the book of Moses. In Deuteronomy 1, Moses entrusts the choice of magistrates to the people, whereas in Exodus 18, he implements Jethro's directive by choosing the judges himself. In Exodus 18, the qualities to be sought in the judges are moral probity and piety, whereas Deuteronomy 1 stresses intellectual discernment.[115]

The 1639 Fundamental Agreement of the New Haven Colony reported that John Davenport, a Puritan clergyman and co-founder of the colony, declared to all the free planters forming the colony that Exodus 18:2, Deuteronomy 1:13, and Deuteronomy 17:15 described the kind of people who might best be trusted with matters of government, and the people at the meeting assented without opposition.[116]

Deuteronomy chapter 2

Archeologists Israel Finkelstein of Tel Aviv University and Neil Asher Silberman noted that Numbers 21:21–25; Deuteronomy 2:24–35; and 11:19–21 report that the wandering Israelites battled at the city of Heshbon, capital of Sihon, king of the Amorites, who tried to block the Israelites from passing through his territory on their way to Canaan. Excavations at Tel Hesban south of Amman, the location of ancient Heshbon, showed that there was no Late Bronze Age city, not even a small village, there. And Finkelstein and Silberman noted that according to the Bible, when the children of Israel moved along the Transjordanian plateau they met and confronted resistance not only in Moab but also from the full-fledged states of Edom and Ammon. Yet the archeological evidence indicates that the Transjordan plateau was very sparsely inhabited in the Late Bronze Age, and most parts of the region, including Edom, mentioned as a state ruled by a king, were not even inhabited by a sedentary population at that time, and thus no kings of Edom could have been there for the Israelites to meet. Finkelstein and Silberman concluded that sites mentioned in the Exodus narrative were unoccupied at the time they reportedly played a role in the events of the Israelites wanderings in the wilderness, and thus a mass Exodus did not happen at the time and in the manner described in the Bible.[117]

Commandments

According to Maimonides

Maimonides cited verses in the parashah for three negative commandments:[118]

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are two negative commandments in the parashah.[120]

- Not to appoint any judge who is unlearned in the Torah, even if the person is generally learned[9]

- That a judge presiding at a trial should not fear any evil person[9]

Liturgy

Some Jews recite the blessing of fruitfulness in Deuteronomy 1:10–11 among the verses of blessing recited at the conclusion of the Sabbath.[121]

"Mount Lebanon . . . Siryon," another name for Mount Hermon, as Deuteronomy 3:9 explains, is reflected in Psalm 29:6, which is in turn one of the six Psalms recited at the beginning of the Kabbalat Shabbat prayer service .[122]

The Weekly Maqam

In the Weekly Maqam, Sephardi Jews each week base the songs of the services on the content of that week's parashah. For parashah Devarim, Sephardi Jews apply Maqam Hijaz, the maqam that expresses mourning and sadness. This maqam is appropriate not due to the content of the parashah, but because this is the parashah that falls on the Shabbat prior to Tisha B'Av, the date that marks the destruction of the Temples.

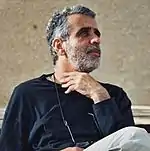

Haftarah

Devarim is always read on the final Shabbat of Admonition, the Shabbat immediately prior to Tisha B'Av. That Shabbat is called Shabbat Chazon, corresponding to the first word of the haftarah, which is Isaiah 1:1–27. Many communities chant the majority of this haftarah in the mournful melody of the Book of Lamentations due to the damning nature of the vision as well as its proximity to the saddest day of the Hebrew calendar, the holiday on which Lamentations is chanted.

Notes

- "Devarim Torah Stats". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2009), pages 2–25.

- Deuteronomy 1:1–3.

- Deuteronomy 1:6–8.

- Deuteronomy 1:9–13.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy, page 6.

- Deuteronomy 1:14–15.

- Deuteronomy 1:16–17.

- Deuteronomy 1:17.

- Deuteronomy 1:19–21.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy, page 8.

- Deuteronomy 1:22. Moses here recounts events told in Numbers 13:1–30.

- Deuteronomy 1:22–24.

- Deuteronomy 1:24–25.

- Deuteronomy 1:26–28.

- Deuteronomy 1:29–31.

- Deuteronomy 1:34–36.

- Deuteronomy 1:37.

- Deuteronomy 1:38.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy, page 12.

- Deuteronomy 1:39.

- Deuteronomy 1:41–42.

- Deuteronomy 1:43.

- Deuteronomy 1:44.

- Deuteronomy 1:46–2:1.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy, page 13.

- Deuteronomy 2:2–3.

- Deuteronomy 2:4–6.

- Deuteronomy 2:8.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy, page 15.

- Deuteronomy 2:9.

- Deuteronomy 2:14–15.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy, page 17.

- Deuteronomy 2:17–19.

- Deuteronomy 2:24.

- Deuteronomy 2:26–29.

- Deuteronomy 2:30.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy, pages 19–20.

- Deuteronomy 2:32–35.

- Deuteronomy 2:36.

- Deuteronomy 3:1–2.

- Deuteronomy 3:3–7.

- Deuteronomy 3:11.

- Deuteronomy 3:12–17.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy, page 23.

- Deuteronomy 3:18–20.

- Deuteronomy 3:21–22.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy, pages 24–25.

- See, e.g., Richard Eisenberg, "A Complete Triennial Cycle for Reading the Torah," in Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement: 1986–1990 (New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2001), pages 383–418.

- Moshe Weinfeld, Deuteronomy 1–11 (New York: Anchor Bible, 1991), volume 5, pages 140–41 (citing von Schuler 1957, pages 36ff).

- "Papyrus Anastasi I: A Satirical Letter," in Edward F. Wente, Letters from Ancient Egypt (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1990), pages 107–08.

- James B. Pritchard, editor, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), page 328.

- Tale of Aqhat (Ugarit, 14th century BCE}, in, e.g., Dennis Pardee, translator, “The ’Aqhatu Legend (1.103),” in William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger Jr., editors, The Context of Scripture: Volume I: Canonical Compositions from the Biblical World (New York: Brill Publishers, 1997), page 343 and note 1.

- For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer, "Inner-biblical Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), pages 1835–41.

- Henry D.M. Spence and Joseph S. Exell, editors, The Pulpit Commentary on Deuteronomy 1 (1909–1919), in (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1977) volume 3 (Deuteronomy, Joshua & Judges), page 1.

- Patrick D. Miller, Deuteronomy (Louisville: John Knox Press, 1990), pages 31–32.

- For more on classical rabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Yaakov Elman, "Classical Rabbinic Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition, pages 1859–78.

- Mishnah Sotah 7:8 (Land of Israel, circa 200 CE), in, e.g., Jacob Neusner, translator, The Mishnah: A New Translation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), page 459; Tosefta Sotah 7:17 (Land of Israel, circa 250 CE), in, e.g., Jacob Neusner, translator, The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction (Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002), volume 1, page 864; Babylonian Talmud Sotah 41a (Sasanian Empire, 6th century), in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sotah: Volume 2, elucidated by Eliezer Herzka, Moshe Zev Einhorn, Michoel Weiner, Dovid Kamenetsky, and Reuvein Dowek, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000), volume 33b, pages 41a3–4.

- Tosefta Sotah 7:12, in, e.g., Jacob Neusner, translator, Tosefta, volume 1, page 863.

- Avot of Rabbi Natan, chapter 34 (700–900 CE), in, e.g., Judah Goldin, translator, The Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1955, 1983), pages 136–37.

- Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 32a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Berachos: Volume 2, elucidated by Yosef Widroff, Mendy Wachsman, Israel Schneider, and Zev Meisels, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997), volume 2, page 32a; see also Babylonian Talmud Yoma 86b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Yoma: Volume 2, elucidated by Eliezer Herzka, Zev Meisels, Abba Zvi Naiman, Dovid Kamenetsky, and Mendy Wachsman, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1998), volume 14, page 86b5; Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 102b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sanhedrin: Volume 3, elucidated by Asher Dicker, Joseph Elias, and Dovid Katz, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1995), volume 49, page 102b.

- Sifre to Deuteronomy 2:3 (Land of Israel, circa 250–350 CE), in, e.g., Jacob Neusner, translator, Sifre to Deuteronomy: An Analytical Translation (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1987), volume 1, pages 26–27.

- Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 16 (early 9th century), in, e.g., Gerald Friedlander, translator, Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer (London, 1916, New York: Hermon Press, 1970), pages 111–12.

- Babylonian Talmud Sotah 35b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sotah: Volume 2, elucidated by Eliezer Herzka, et al., volume 33b, pages 35b1–2.

- Genesis Rabbah 16:3 (Land of Israel, 5th century), in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Genesis (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 1, pages 126–27.

- Tosefta Avodah Zarah 8:4, in, e.g., Jacob Neusner, translator, Tosefta, volume 2, pages 1291–92; see also Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 56a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sanhedrin: Volume 2, elucidated by Michoel Weiner and Asher Dicker, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1994), volume 48, page 56a5; Genesis Rabbah 34:8, in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Genesis, volume 1, pages 271–72.

- Tosefta Menachot 7:8, in, e.g., Jacob Neusner, translator, Tosefta, volume 2, page 1435.

- Babylonian Talmud Eruvin 100b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Eruvin: Volume 2, elucidated by Yisroel Reisman and Michoel Weiner, edited by Hersh Goldwurm (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1991), volume 8, pages 100b2–3; see also Babylonian Talmud Nedarim 20b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Nedarim: Volume 1, elucidated by Eliezer Herzka, Yosef Davis, Hillel Danziger, Zev Meisels, Avrohom Neuberger, Henoch Moshe Levin, Yehezkel Danziger, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000), volume 29, page 20b4.

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 1:10 (Land of Israel, 9th century), in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 7, pages 8–9.

- Sifre to Deuteronomy 13:3, in, e.g., Jacob Neusner, translator, Sifre to Deuteronomy, volume 1, page 44.

- Babylonian Talmud Yevamot 86b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Yevamos: Volume 3, elucidated by Yosef Davis, Dovid Kamenetsky, Moshe Zev Einhorn, Michoel Weiner, Israel Schneider, Nasanel Kasnett, and Mendy Wachsman, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2005), volume 25, page 86b.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 18a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sanhedrin: Volume 1, elucidated by Asher Dicker and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Hersh Goldwurm (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1993), volume 47, page 18a1.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 7b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sanhedrin: Volume 1, elucidated by Asher Dicker and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Hersh Goldwurm, volume 47, page 7b3.

- See, e.g., Exodus 22:20; 23:9; Leviticus 19:33–34; Deuteronomy 1:16; 10:17–19; 24:14–15 and 17–22; and 27:19.

- Babylonian Talmud Bava Metzia 59b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Bava Metzia: Volume 2, elucidated by Mordechai Rabinovitch and Tzvi Horowitz, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1993), volume 42, page 59b3.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 7b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sanhedrin: Volume 1, elucidated by Asher Dicker and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Hersh Goldwurm, volume 47, page 7b4.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 8a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sanhedrin: Volume 1, elucidated by Asher Dicker and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Hersh Goldwurm, volume 47, page 8a1.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 6b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sanhedrin: Volume 1, elucidated by Asher Dicker and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Hersh Goldwurm, volume 47, pages 6b2–3.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 6b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sanhedrin: Volume 1, elucidated by Asher Dicker and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Hersh Goldwurm, volume 47, page 6b1.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 8a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sanhedrin: Volume 1, elucidated by Asher Dicker and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Hersh Goldwurm, volume 47, pages 8a1.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 8a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sanhedrin: Volume 1, elucidated by Asher Dicker and Abba Zvi Naiman, edited by Hersh Goldwurm, volume 47, pages 8a1–2.

- Babylonian Talmud Sotah 47b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sotah: Volume 2, elucidated by Eliezer Herzka, et al., volume 33b, pages 47b4–5.

- Babylonian Talmud Sotah 34b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Sotah: Volume 1, elucidated by Eliezer Herzka, et al., volume 33b, page 34b1.

- Babylonian Talmud Chullin 90b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Chullin: Volume 3, elucidated by Eliezer Herzka and Mendy Wachsman, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2003), volume 63, page 90b; Babylonian Talmud Tamid 29a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Me’ilah: Tractate Kinnim: Tractate Tamid: Tractate Middos, elucidated by Avrohom Neuberger, Nasanel Kasnett, Abba Zvi Naiman, Henoch Moshe Levin, Eliezer Lachman, and Ari Lobel, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2004), volume 70, page 29a.

- Mekhilta, Bahodesh, chapter 2 (Land of Israel, late 4th century), in, e.g., Jacob Z. Lauterbach, Translator, Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1933, reissued 2004), volume 2, page 296–97.

- Mishnah Taanit 4:6, in, e.g., Jacob Neusner, translator, Mishnah, page 315; Babylonian Talmud Taanit 26b, 29a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Taanis, elucidated by Mordechai Kuber and Michoel Weiner, edited by Hersh Goldwurm (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1991), volume 19, pages 26b, 29a.

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 89b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Shabbos: Volume 3, elucidated by Yosef Asher Weiss, Michoel Weiner, Asher Dicker, Abba Zvi Naiman, Yosef Davis, and Israel Schneider, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1996), volume 5, page 89b.

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 1:17, in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy, volume 7, pages 19–20.

- Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 18a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Kiddushin: Volume 1, elucidated by David Fohrman, Dovid Kamenetsky, and Hersh Goldwurm, edited by Hersh Goldwurm (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1992), volume 36, page 18a.

- Babylonian Talmud Nazir 23b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Nazir: Volume 1, elucidated by Mordechai Rabinovitch, edited by Hersh Goldwurm (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1992), volume 31, page 23b.

- Babylonian Talmud Bava Kamma 38a–b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Bava Kamma: Volume 2, elucidated by Avrohom Neuberger, Reuvein Dowek, Eliezer Herzka, Asher Dicker, Mendy Wachsman, Nasanel Kasnett, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2001), volume 39, pages 38a4–b1.

- Babylonian Talmud Gittin 38a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Gittin: Volume 1, elucidated by Yitzchok Isbee, Nasanel Kasnett, Israel Schneider, Avrohom Berman, Mordechai Kuber, edited by Hersh Goldwurm (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1993), volume 34, page 38a.

- See Mishnah Taanit 4:8, in, e.g., Jacob Neusner, translator, Mishnah, pages 315–16; Babylonian Talmud Taanit 26b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Taanis, elucidated by Mordechai Kuber and Michoel Weiner, edited by Hersh Goldwurm, volume 19, page 26b.

- Babylonian Talmud Taanit 30b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Taanis, elucidated by Mordechai Kuber and Michoel Weiner, edited by Hersh Goldwurm, volume 19, page 30b; Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 121a–b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Bava Basra: Volume 3, elucidated by Yosef Asher Weiss, edited by Hersh Goldwurm (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1994), volume 46, pages 121a–b.

- Aryeh Kaplan, The Living Torah (New York: Maznaim Publishing Corporation, 1981), page 763.

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 5:13, in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy, volume 7, pages 114–16.

- Babylonian Talmud Avodah Zarah 25a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Avodah Zarah: Volume 1, elucidated by Avrohom Neuberger, Nasanel Kasnett, Zev Meisels, and Dovid Kamenetsky, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2001), volume 52, page 25a; Babylonian Talmud Taanit 20a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Taanis, elucidated by Mordechai Kuber and Michoel Weiner, edited by Hersh Goldwurm, volume 19, page 20a.

- Numbers Rabbah 19:29 (12th century), in, e.g., Judah J. Slotki, translator, Midrash Rabbah: Numbers (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 6, pages 778–79.

- Numbers Rabbah 19:32, in, e.g., Judah J. Slotki, translator, Midrash Rabbah: Numbers, volume 6, pages 780–82.

- Numbers Rabbah 16:18, in, e.g., Judah J. Slotki, translator, Midrash Rabbah: Numbers, volume 6, page 685.

- Babylonian Talmud Nidah 24b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli: Tractate Niddah: Volume 1, elucidated by Hillel Danziger, Moshe Zev Einhorn, and Michoel Weiner, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1996), volume 71, page 24b.

- Numbers Rabbah 20:3, in, e.g., Judah J. Slotki, translator, Midrash Rabbah: Numbers, volume 6, pages 787–88.

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 2:5, in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy, volume 7, page 33.

- Leviticus Rabbah 11:6 (Land of Israel, 5th century), in, e.g., Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, translators, Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 4, pages 141–43; Song of Songs Rabbah 1:7 § 3 (1:44 or 45) (6th–7th centuries), in, e.g., Maurice Simon, translator, Midrash Rabbah: Song of Songs (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 9, pages 65–66.

- For more on medieval Jewish interpretation, see, e.g., Barry D. Walfish, "Medieval Jewish Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition, pages 1891–1915.

- Zohar, Shemot, part 2, page 201a (Spain, late 13th century), in, e.g., Daniel C. Matt, translator, The Zohar: Pritzker Edition (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2011), volume 6, pages 145–46.

- Maimonides, Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Sanhedrin veha’Onashin haMesurin lahem, chapter 2, ¶ 6 (Egypt, circa 1170–1180), in, e.g., Eliyahu Touger, translator, Mishneh Torah: Sefer Shoftim (New York: Moznaim Publishing, 2001), pages 24–25.

- Maimonides, Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Sanhedrin veha’Onashin haMesurin lahem, chapter 2, ¶ 7, in, e.g., Eliyahu Touger, translator, Mishneh Torah: Sefer Shoftim, pages 24–27.

- Abraham ibn Ezra, Commentary on the Torah (mid-12th century), in, e.g., H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, translators, Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Deuteronomy (Devarim) (New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 2001), volume 5, page 12.

- Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, editor, The Sapirstein Edition Rashi: The Torah with Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated: Devarim/Deuteronomy (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997), volume 5, pages 35–36.

- Torah With Ramban's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated: Devarim/Deuteronomy, edited by Nesanel Kasnett, Yaakov Blinder, Yisroel Schneider, Leiby Schwartz, Nahum Spirn, Yehudah Bulman, Aron Meir Goldstein, and Feivel Wahl (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2008), volume 7, pages 65–67.

- Carl Sagan, “Journeys in Space and Time,” in Cosmos: A Personal Voyage (Cosmos Studios, 1980), episode 8.

- W. Gunther Plaut, The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition, revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern (New York: Union for Reform Judaism, 2006), page 1163.

- Jeffrey H. Tigay, The JPS Torah Commentary: Deuteronomy: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1996), page 11.

- Robert Alter, The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary (New York: W.W. Norton, 2004), page 881.

- The Fundamental Agreement or Original Constitution of the Colony of New Haven, June 4, 1639, in Philip B. Kurland and Ralph Lerner, editors, The Founders' Constitution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), volume 5, pages 45–46.

- Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts (New York: The Free Press, 2001), pages 63–64.

- Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Negative Commandments 58, 276, 284 (Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180), in Maimonides, The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides, translated by Charles B. Chavel (London: Soncino Press, 1967), volume 2, pages 55–56, 259, 265–66.

- Deuteronomy 3:22.

- Charles Wengrov, translator, Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education (Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1988), volume 4, pages 238–45.

- Menachem Davis, editor, The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals with an Interlinear Translation (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002), page 643.

- Reuven Hammer, Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals (New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003), page 20.

Further reading

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Biblical

- Genesis 14:5–6 (Rephaim, Emim, Horites); 15:5 (numerous as stars); 22:17 (numerous as stars); 26:4 (numerous as stars).

- Exodus 4:21; 7:3; 9:12; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:10; 14:4, 8 (hardening of heart); 18:13–26 (appointment of the chiefs); 32:34 (command to lead the people to the Promised Land).

- Numbers 10:11–34 (departure for the Promised Land); 13:1–14:45 (the spies); 20:14–21; 21:21–35 (victories over Sihon and Og); 27:18–23; 32:1–33.

- Deuteronomy 9:23.

- Joshua 1:6–9, 12–18; 11:20 (hardening of heart); 13:8–32.

- Amos 5 (the establishment of justice as necessary for God's Presence).

- Psalm 82 (God as the epitome of justice).

Early nonrabbinic

Classical rabbinic