Video game clone

A video game clone is either a video game or video game console very similar to, or heavily inspired by, a previous popular game or console. Clones are typically made to take financial advantage of the popularity of the cloned game or system, but clones may also result from earnest attempts to create homages or expand on gameplay ideas presented in the original game. Legally, video game clones are not generally considered to be copyright infringement as gameplay elements are broadly uncopyrightable, an essential factor for creative development of new games based on past ideas. More recent case law has identified that game developers can protect their games' look and feel from clones, while methods like patents, trademarks, and industry regulation also help to fend off clones.

Overview

Cloning a game in digital marketplaces is common. It is hard to prevent and easy to compete with existing games. Developers can copyright the graphics, title, story, and characters, but have more difficulty protecting software design and game mechanics. A patent for the mechanics is possible but expensive and time-consuming.[1] Popular game concepts often lead to that concept becoming incorporated or expanded upon by other developers. In other cases, games may be developed with clear influence from one or more earlier games. Such derivations are not always considered clones though the term may be used to make a comparison between games. As copyright law does not protect gameplay concepts, the reuse of such ideas is generally considered acceptable. For example, Grand Theft Auto III spurred a number of games that have been called GTA clones but which are not direct copies of assets or gameplay ideas.[2] In these cases, games that are "clones" of another are generally not implied to have committed any intellectual property infractions, and otherwise considered legally acceptable practices, although calling such games clones is generally considered derogatory.[3]

True video games clones occur when competitors, on seeing the success of a video game title, attempt to compete by creating a near-copy of the existing game with similar assets and gameplay with little additional innovation; developer Jenova Chen compared the nature of these clones similar to plagiarism in which there is little attempt to distinguish the new work from the original.[4] Video game clones are seen by those developing them as low risk; knowing that a game or genre is popular, developing a clone of that game would appear to be a safe and quick investment, in contrast with developing a new title with unknown sales potential.[5] Further, cloning of games from smaller developers, particularly indie developers, is more frequent as these small teams lack the financial resources to pursue legal recourse. Instead, these teams often appeal to social influence to try to have the cloner take corrective actions.[1]

History

Hardware cloning (1970s–2000s)

Cloning of video games came as early with arcade games shortly after the release of Pong by Atari, Inc. in 1972. Its success led to numerous companies buying a copy of the arcade machine to try to make their own versions. Atari's Nolan Bushnell called these vendors "jackals", but took no legal action and instead focused on making new games to try to outpace them.[6] Bushnell also maintained contractual agreements with Bally Manufacturing and Midway Manufacturing; in the case of Midway, Atari providing Midway with a licensed Pong design that Midway released as Winner.[7]

One of those companies that had copied Pong was Allied Leisure, which had released its Paddle Battle arcade game in early 1973. When the market shifted from the two-player to four-player table tennis versions in mid-1973, Allied Leisure produced two new arcade games, Tennis Tourney and Ric-o-chet, both which Midway stated caused demand for the two-player Winner to drop dramatically. To stay competitive, Midway acquired one of Allied's games to compare the printed circuit board to that from Winner as to determine what was the new components for making it a four-player game, and added that to Winner's board, and released as Winner IV. Allied Leisure filed suit against Midway claiming copyright infringement of using its printed circuit board design in making Winner IV and unfair competition, but the judge failed to agree to a preliminary injunction, ruling that while a drawing of the printed circuit board may have copyright protection, the physical board itself would not and instead would be covered by patents, which were not involved in this case. The case was settled out of court in 1974 for undisclosed terms, believed due to factors relating to a short downturn in the market, as David Braun, the CEO of Allied Leisure had said in 1974 that "th[e] video game is yesterday's newspaper." The settlement was also likely due to pressure from the patent issues that had arisen around the home versions of Pong in the first generation of consoles that were occurring simultaneously.[7]

The base ideas of a home video game console were developed by Ralph H. Baer while working at Sanders Associates, where in 1966 he began work on what ultimately became his "Brown Box" prototype. After securing approval of a proposal for his idea from his superiors, Baer worked with Sanders engineers Bill Harrison and Bill Rusch to execute its design while keeping it within a low cost target.[8] By 1967, the optimized design was ready to be shopped to other manufacturers as Sanders was not in that market area.[9] To protect the idea, Sanders applied for and received three patents in Baer's, Harrison's, and Rusch's names, covering their "television gaming apparatus"; this included the 1974 reissued U.S. Patent RE28,507 for a "television gaming apparatus",[10] U.S. Patent 3,659,285 for a "television gaming apparatus and method",[11] and U.S. Patent 3,728,480 for a "television gaming and training apparatus".[12] Sanders eventually licensed the technology and the patents to Magnavox, which used it to make the Magnavox Odyssey, released in 1972. In 1974, Magnavox sued several companies creating and distributing table-tennis arcade games including Atari and Midway. This case was ultimately decided in Magnavox's favor in early 1977. Atari settled before the final judgement and agreed to pay Magnavox US$1,500,000 for a perpetual license to the three patents and other technology sharing agreements.[13]

However, just as with the arcade version, the home version of Pong drew a number of third-party hardware manufacturers to make Pong clones on the market, to a point where it was estimated that Atari's Pong console represented only about a third of sales of home Pong consoles.[14] Magnavox continued to pursue action against these Pong clones using the three patents, estimated to have won over US$100 million in damages from suits and settlements through the lifetime of the patents.[15][16][17][18] However, threats of lawsuits did not prevent more clones of the home console systems from being built, as these dedicated consoles were relatively risk free and easy to manufacture. This led to a flooded dedicated-game console market, and creating the industry's first market crash in 1977.[19][20]:81–89

The original Atari Pong home console, labeled with Sears' "Tele-games" brand

The original Atari Pong home console, labeled with Sears' "Tele-games" brand The Russian "Турнир" ("Tournament") Pong clone

The Russian "Турнир" ("Tournament") Pong clone The Magnavox Odyssey

The Magnavox Odyssey The Overkal, made by Inter Electrónica S.A. in 1974, a clone of the Magnavox Odyssey for the Spanish market

The Overkal, made by Inter Electrónica S.A. in 1974, a clone of the Magnavox Odyssey for the Spanish market

Eventually, home consoles switched from built-in games to cartridge-based systems within the second generation, making it more difficult to clone at the hardware level. However, off-brand manufacturers attempted to make bootleg copies of these consoles that has a similar form as the known console, but typically could only play built in games frequently on a liquid-crystal display (LCD). Other bootleg consoles would take the workings of older systems and repackage them in a newer housing that appears like the known consoles capable of playing the games from the original system.[21] The latter was particularly true of consoles that attempted to clone the Nintendo Entertainment System (known as the Famicom system in Japan), which was not available in some countries in the Eastern European and Chinese regions, leading manufacturers within those nations to make numerous bootleg versions, knowing that it would be near-impossible for Nintendo to seek legal action against them.[22][23]

The Nintendo DS

The Nintendo DS Neo Double Games, mimicking the design of the DS, but games are not digital, and are played on a segmented LCD screen

Neo Double Games, mimicking the design of the DS, but games are not digital, and are played on a segmented LCD screen The Nintendo Super Famicom console

The Nintendo Super Famicom console The Pegasus, sold only in Eastern European states, was a Famicom clone though styled after the Super Famicom system

The Pegasus, sold only in Eastern European states, was a Famicom clone though styled after the Super Famicom system

Software cloning (1980s–present)

While hardware itself became difficult to clone, the software of games were subsequently used in unlicensed copies for other systems. Cloning of arcade games was popular during the arcade's "golden age" in the early 1980s. Arcade games, prior to mass production, were made in limited numbers for field testing in public spaces; once news got out that a new arcade game from industry leaders like Atari was out in the open, third-party competitors would be able to scope the game and rush to make a clone of the game, either as a new arcade game or for home consoles; an occurrence which happened with Missile Command in 1980. This ultimately diluted the market for new arcade games.[24] BYTE reported in December 1981 that at least eight clones of Atari, Inc.'s arcade game Asteroids existed for personal computers.[25] The magazine stated in December 1982 that that year "few games broke new ground in either design or format ... If the public really likes an idea, it is milked for all it's worth, and numerous clones of a different color soon crowd the shelves. That is, until the public stops buying or something better comes along. Companies who believe that microcomputer games are the hula hoop of the 1980s only want to play Quick Profit".[19] The degree of cloning was so great that in 1981, Atari warned in full-page advertisements "Piracy: This Game is Over", stating that the company "will protect its rights by vigorously enforcing [its] copyrights and by taking appropriate action against unauthorized entities who reproduce or adapt substantial copies of ATARI games", like a home-computer clone.[26]

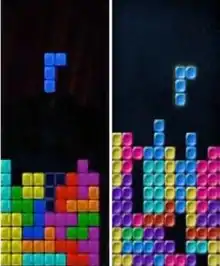

Third parties continued to attempt or clone concepts or ideas from popular and successful games. Games like Tetris and Breakout[27] inspired many games that used similar core concepts but expanded beyond that; the Breakout-inspired Arkanoid itself inspired many other clones that built upon its unique additions to Breakout. Gameplay elements of Street Fighter II and Mortal Kombat became common gameplay elements in the fighting game genre,[28][29][30] A large number of games that tried to capitalize on the success of the 3D adventure game Myst were grouped as "Myst clones".[31] Some video game genres are founded by archetypal games of which all subsequent similar games are considered derivatives; notably, early first-person shooters were often called "Doom clones",[32] while the success of the open-world formula in Grand Theft Auto led to the genre of GTA clones.[2] The genre of endless runners is based on the success and simplicity of the game Canabalt.[33] Such cloning can also cause a relatively-sudden emergence of a new genre as developers attempt to capitalize on the interest. The battle royale genre grew rapidly after the success of PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds and Fortnite Battle Royale across 2017 and 2018,[34] while Dota Auto Chess released in January 2019 spawned several commercial games in the auto battler genre by mid-2019.[35][36]

Another type of clone arose from developers in the open source and indie game venues, where the developers seek to recreate the gameplay of a popular title through reverse engineering, adding their own creative assets, and releasing the game typically for free and in homage to the original title. This allows the teams and users to expand upon original elements of the commercial game, such as software bugs that were not fixed, improving gameplay concepts, support for newer computers or console systems, or adding new ideas to the base gameplay principles, as well as enabling gameplay extensions through user-generated mods or add-ons. Some examples of these clones include Freeciv based on the Civilization series,[37] Osu! based on Osu! Tatakae! Ouendan,[38] and Frets on Fire based on Guitar Hero.[39] The open source nature of these clones also enable new utilities, such as developing artificial intelligence agents that have learned and improved their play in Freeciv which in turn can help advance artificial intelligence research.[40] Such games must be careful not to use the original game's assets or could face legal issues. OpenSC2K, an open-source recreation of SimCity 2000, was shut down by Electronic Arts after it was found that OpenSC2K used assets from SimCity 2000.[41] In the area of indie games, while there may be cloning of such games, indie developers tend to rely on an informal code of honor to shun those that do engage in cloning.[42]

New concerns related to cloned video games came with the rise of social network and mobile games, typically which were offered as freemium titles to entice new players to play.[43] The low cost, ease and simplicity of the tools needed to develop these made cloning in that sector a significant problem.[44][45][46] For example, Flappy Bird had been cloned dozens of times due to programming code clearinghouses offering templated code to which others could easily add their own art assets.[46] The creators of Threes! spent 14 months developing the game and tuning its mechanics, but the first clone was released 21 days after Threes! and the original was quickly overshadowed by 2048, a clone that was developed over a weekend.[47][48] In the early period of social media games around 2012, Zynga had gained a negative reputation of making copycat clones in that space.[49] However, according to their lead gameplay designer, Brian Reynolds, that they see potential new genres and game ideas that gain popularity, and then strive to add their own innovation and concepts to at, so that "[their] goal is to have the highest-quality thing".[50]

Another major area of concern for software clones arises within China. From 2000 to 2015, the Chinese government had numerous restrictions on imports of hardware and software, and access to non-Chinese storefronts. While this allowed gaming on personal computers to flourish within China, the cost of acquiring both hardware and software was too expensive for many, leading to Chinese developers to create low-cost clones of popular Western and Japanese titles for the Chinese market, which persist today.[51] Foreign companies are faced with difficulties in seeking legal action against the Chinese developers that have created these clones, making cloning a far less risky process.[51] Thus, it is common for popular games from both Western and Japanese markets to see near-exact clones appear within China, often within weeks of the original game's release. A notable example is a clone of Blizzard Entertainment's Hearthstone called Sleeping Dragon: Heroes of the Three Kingdoms created by Chinese developer Unico, released within a few months of Hearthstone's beta release. Blizzard was ultimately successful in suing Unico for US$1.9 million in damages in 2014.[52] In other cases, clones are made to address elements of the original game that are unsuitable under China's content restriction laws; for example, Tencent, which operated the publishing of PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds in China, was forced to pull the game due to content related to violence and terrorism, and instead replaced it with a clone, Game for Peace, which otherwise reused assets from Battlegrounds but removed blood and gore.[53]

Legal aspects

Most legal considerations related to video game clones are discussed in the context of United States copyright and intellectual protection laws, which generally have equivalent features in most other regions.

General concepts of copyright protection

In the United States, the underlying source code, and the game's artistic elements, including art, music, and dialog, can be protected by copyright law.[54] However, gameplay elements of a video game are generally ineligible for copyright;[54] gameplay concepts fall into the idea–expression distinction that had been codified in the Copyright Act of 1976, in that copyright cannot be used to protect ideas, but only the expression of those ideas.[55] The United States Copyright Office specifically notes: "Copyright does not protect the idea for a game, its name or title, or the method or methods for playing it. Nor does copyright protect any idea, system, method, device, or trademark material involved in developing, merchandising, or playing a game. Once a game has been made public, nothing in the copyright law prevents others from developing another game based on similar principles."[56] Courts also consider scènes à faire (French for "scenes that must be done") for a particular genre as uncopyrightable; games involving vampires, for example, would be expected to have elements of the vampire drinking blood and driving a stake through the vampire's heart to kill him.[57] It is generally recognized in the video game industry that borrowing mechanics from other games is common practice and often a boon for creating new games,[1] and their widespread use would make them ineligible for legal copyright or patent protection.[54][58]

The United States passed the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) in 1998 as part of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Performances and Phonograms Treaty. Broadly, the DMCA prohibits hardware and software anti-circumvention tools, such as reading an encrypted optical disc. For both video game hardware manufacturers and for software developers and publishers, this helps to protect their work from being copied, disassembled, and reincorporated into a clone. However, the DMCA has been problematic for those in video game preservation that wish to store older games on more permanent and modern systems. As part of the DMCA, the Library of Congress adds various exemptions which have included the use of anti-circumvention for museum archival purposes, for example.[59]

In present-day case law driven by decisions in the United States legal system, video game copyrights come from two forms. The first is by its source code or equivalent, as determined by the 1983 decision in Apple Computer, Inc. v. Franklin Computer Corp. that software code can be considered a "literary work" and thus subject to copyright protection. The second form is as an audiovisual work, as determined in the 1982 case Stern Electronics, Inc. v. Kaufman; while video games present images and sound that are not in a fixed form, the repetitive use of these in a systematic response to player's actions was sufficient for copyright protections as audiovisual works.[55][60] In the case of the earlier hardware before programmable computer chips, copyright was also recognized by the impression of software based on the circuit board patterns and features that made games work as a form of fixation, as established by both Stern and the 1982 case Midway Mfg. Co. v. Dirkschneide, in which Midway successfully sued a company that was reselling repackaged versions of their arcade games Pac-Man, Galaxian and Rally-X.[60]

Up until 2012, U.S. courts were reluctant to find for copyright infringement of clones. Driving case law in the United States was principally through the case Atari, Inc. v. Amusement World, Inc. (547 F. Supp. 222, 1982). Atari had sued Amusement World claiming that its video game Meteos violated their copyright on Asteroids. The court did find twenty-two similarities between the two games, but ruled against Atari's claims, citing these elements as scènes à faire for games about shooting at asteroids.[57] The case established that "look and feel" of a game could not easily be protected.[61] Attorney Stephen C. McArthur, writing for Gamasutra, said that during this period, courts opted to take a more lax view to balance innovation in the industry and prevent overzealous copyright protection that could have one company claim copyright on an entire genre of games.[57] At best, copyright holders could challenge clones by threatening cease and desist letters, or on other intellectual property rights such as trademarks.[62]

Shifts since 2012

A shift in legal options for developers to challenge clones arose from the 2012 federal New Jersey district court decision in Tetris Holding, LLC v. Xio Interactive, Inc. that ruled in favor of The Tetris Company, the licensees of the Tetris copyright, over the clone Mino, developed by Xio Interactive, which used the same gameplay as Tetris but with different art assets. The developers for Mino has cited in their defense that they only used the uncopyrightable gameplay elements of Tetris in Mino. The court ruled that copyright law was in favor of the Tetris Company's claim, as the gameplay was copied without changes, and while the art assets were new, the "look and feel" of Mino could be easily confused for that of Tetris.[62][57][63] The court also recognized that since the time Tetris had been released and when Mino was published, there was enough new technology in graphics that Mino could have added new forms of expression to the base gameplay to better distinguish from the idea of Tetris, such as how to display the tetraminos or the animation of how they fell, but instead copied very closely what Tetris had done, thus making it more likely a copyright violation.[60] While only a district court decision and not binding outside of New Jersey, this served as case law for other developers to fend off "look-and-feel" clones.[64]

The same reasoning was found in a similar case that was occurring nearly simultaneously with the Tetris decision, in which SpryFox LLC, the developers of the mobile game Triple Town, successfully defended their game from a clone, Yeti Town, developed by 6Waves, through court settlement after the judge gave initially rulings in favor of SpryFox.[57] These rulings suggested that there was copyright protection on the gameplay mechanics despite drastic differences in the games' art assets, though other factors, such as prior agreements between SpryFox and 6Waves, may have also been involved.[57]

Both the Tetris and Triple Town cases have established new but limited case law on "look and feel" that can be used to challenge video game clones in court.[55][61][65][66]

Other methods of protection

Patents are frequently used to protect hardware consoles from cloning. Though patents do not cover elements like the form and shape of a console, they can be used to protect the internal hardware and electronic components, as Magnavox had used at the onset of the arcade game and home console clones.[67] Notably, many of the patents for the Famicom and NES expired in 2003 and 2005, respectively, leading to additional grey market hardware clones within a short time. However, Nintendo had built other intellectual property protection into their system, specifically the 10NES lock-out system, covered by copyright law, that would allow only authorized games to be played on their hardware.[68]

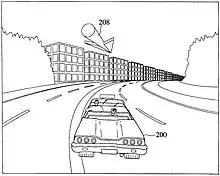

Less frequently, patents have been used to protect video game software elements.[69][70][71][72] Notably, Sega had filed a 1998 United States patent for the gameplay concepts in Crazy Taxi.[73] The company subsequently sued Fox Interactive for patent infringement over their title The Simpsons: Road Rage, citing that the latter game was developed to "deliberately copy and imitate" the Crazy Taxi game.[74] The case was ultimately settled out of court.[75]

Another approach some companies have used to prevent clones is via trademarks as to prevent clones and knockoffs. Notably, King have gotten a United States trademark on the word "Candy" in the area of video games to protect clones and player confusion for their game Candy Crush Saga. They have also sought to block the use of the word "Saga" in the trademark filing of The Banner Saga for similar reasons, despite the games having no common elements.[76] Within the European Union, one can register for a European Union trade mark that includes multimedia elements, which would allow a developer or publisher to trademark a specific gameplay element that is novel from past games, providing a different route for them to protect their work from cloning. For example, Rebellion Developments filed to register its "Kill Cam" mechanic as a trademark from its series Sniper Elite in October 2017, though as of February 2018, the application is still being reviewed.[77]

Other case law

Other notable legal actions involving video game clones include:

- Atari sought an injunction in 1982 to block the sale of K.C. Munchkin for the Phillips-Magnavox Odyssey², citing excessive similarities to its Atari 2600 version of Pac-Man. Though the court initially denied the injunction, Atari won on appeal; the court noted that though K.C. Munchkin offered different features such as moving walls and fewer dots in the maze to eat, "substantial parts were lifted; no plagiarist can excuse the wrong by showing how much of his work he did not pirate".[78]

- Data East sued Epyx over copyright violations from Data East's Karate Champ used in Epyx's World Karate Championship. Similar to Asteroids vs. Meteors, the court ruled in favor of Epyx, stating that while many elements were similar, they were necessary as part of karate championship-based game, and the remaining copyrightable elements were substantially different.[57]

- Capcom filed a 1994 lawsuit against Data East over their fighting game, Fighter's History, which Capcom claimed cloned characters, art assets, and move sets from Street Fighter II. The court ruled against Capcom, stating that while some elements may have been similar, no direct measure of willful copying could be found; the court further found that many of the characters in Street Fighter II were already based on public domain stereotypical fighters, and were ineligible for copyright protection.[57][79][80][81]

- In August 2012, Electronic Arts (EA), via its Maxis division, put forth a lawsuit against Zynga, claiming that its Facebook game, The Ville was a ripoff of EA's own Facebook game, The Sims Social. The lawsuit challenges that The Ville not only copies the gameplay mechanics of The Sims Social, but also uses art and visual interface aspects that appear to be inspired by The Sims Social. Zynga has long been criticized by the video game industry as cloning popular social and casual games from other developers,[82][83][84] a practice common throughout the social game genre.[85][86] In past cases, Zynga's clones have typically been from smaller developers without the monetary resources to pursue legal action (as in the case of Tiny Tower by NimbleBit, which Zynga has cloned in their game, Dream Heights) or that are willing to settle out of court (as in the case of Zynga's Mafia Wars, which was accused of cloning David Maestri's Mob Wars).[83] Pundits have noted that EA, unlike these previous developers, are financially backed to see the case to completion; EA themselves have stated in the lawsuit that "Maxis isn’t the first studio to claim that Zynga copied its creative product. But we are the studio that has the financial and corporate resources to stand up and do something about it."[87] The two companies settled out of court on undisclosed terms in February 2013.[88]

United Kingdom

Copyright law in the United Kingdom is set by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, but this does not specifically account for video games under any of the works eligible for copyright. Instead, video games are considered protected by copyright in their parts.[89] The computer code or other fixed medium is considered copyrightable, and the game's presentation can be copyrighted as a literary work or dramatic work, while elements like character design, art and sound and music can also be copyrighted.[89] Other facets, like the look and feel or game mechanics, are not considered eligible for copyrightable.[69][89]

European Union

The European Union (EU) as a body of member nations sets policies for copyright and other intellectual property protections that are then to be supported by laws passed at the national levels, allowing individual nations to include additional restrictions within the EU directives. Multiple EU directives have been issued related to copyright that affect video games, but at the core, the Computer Programs Directive of 1991 provide for copyright protection of video games in their source code and all its constituent parts in its fixed format, such as on an optical disc or printed circuit. The audio, visual and other creative elements of a game themselves are not directly covered by any EU directive, but have been enshrined in national laws as a result of the Berne Convention of which the EU and its member states are part of, with video games either expressly called out as cinematographic works or more broadly under audiovisual works. At least one case at the European Court of Justice has ruled similarly to the United States that ideas like gameplay concepts cannot be copyrighted but it is their form of expression that can merit copyrightability.[90]

Patents on software and video games cannot be easily obtained in the European Union, unless it can be demonstrated that there is a significant technical effect beyond the interaction of the hardware and the software.[90]

Japan

Japan's copyright laws are similar to the United States in that a form of artistic expression in a fixed medium is sufficient for copyright protection. Japan is also a member of the Berne convention. Video games, and computer code in general, are considered to fall under copyright as they are a "work of authorship" as "a production in which thoughts or emotions are expressed in a creative way and which falls in the literary, scientific, artistic or musical domain."[91] Video games being eligible for copyrights in the same manner as cinematic works were established through three cases related to video game clones from 1982 to 1984, in which Japan's courted ruled, collectively, that the act of storing data into a computer's read-only memory (ROM) constitutes copying and thus unauthorized copies can be violations of copyright, that similarly hardware circuitry can carry software information and is also copyrightable, and that video games can contain artistic expression that is protected by copyright.[91] These cases gave video games stronger protections for copyright than before, as Japan's courts typically put more onus on plaintiffs in copyright infringement cases to demonstrate similarity, and the fair use allowances tended to be more lax.[92]

As part of the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty, Japan amended its copyright laws in 1999 to prohibit hardware and software anti-circumvention devices, basing its language on the United States' own DMCA.[93]

China

China's legal framework to copyright does recognize individual elements video games as an eligible work for copyrightability with individual creative assets as being copyrightable, but does not have similar provisions as most other nations to recognize the fixed form of publication as also having copyright nor the work as a whole having copyright like a cinematographic work. These last elements have in part enabled enabled widespread copyright theft within the country, not just of video games but other works.[94] The relatively lax copyright rules enables clones based on reskinning an existing game, replacing the art assets with new ones but otherwise not changing the game's code.[89] China's copyright code also makes it difficult to take action on modification of copyrighted characters as these are not explicitly written into Chinese law, which has allowed widespread unlicensed use of others' intellectual property in Chinese games.[94][95] Though the government has introduced more stringent copyright laws in recent years and harsher penalties for violations, video game clones still persist in China.[94]

One of the first major copyright cases over a video game in China was filed in 2007 by Nexon against Tencent, asserting that Tencent's QQ Tang had copied their Pop Tag. The court's decision in favor of Tencent fixed two concepts that remained part of case law: access to the original game, and whether there was substantial similarity in the claimed elements that violated copyright. The case also established that in considering copyrights of the individual elements, there must be a threshold of originality to be copyrightable.[89] A second key case in 2018 occurred when Woniu Technology, the creators of Taiji Panda, sued Tianxiang Company over their mobile game Hua Qian Gu as a reskinned clone of Taija Panda. While Tianxiang attempted to argue that the overall game could not be copyrighted, the court established precedence that a video game fell into the category of cinematographic works, and that the expression of gameplay can be copyrighted, establishing this principle in case law.[89]

Industry regulation

More recently, with the popularity of social and mobile game stores like Apple's App Store for iOS system and Google Play for Android-based systems, a large number of likely-infringing clones have begun appearing.[96] While such storefronts typically include a review process before games and apps can be offered on them, these processes do not consider copyright infringement of other titles. Instead, they rely on the developer of the work that has been cloned to initiate a complaint regarding the clone, which may take time for review. The cloned apps often are purposely designed to resemble other popular apps by name or feel, luring away purchasers from the legitimate app, even after complaints have been filed.[97][98] Apple has released a tool to streamline claims of app clones to a team dedicated to handle these cases, helping to bring the two parties together to try to negotiate prior to action.[99] While Apple, Google, and Microsoft took steps to stem the mass of clones based on Swing Copters after its release, experts believe it is unlikely that these app stores will institute any type of proactive clone protection outside of clear copyright violations, and these experts stress the matter is better done by the developers and gaming community to assure the original developer is well known, protects their game assets on release, and gets the credit for the original game.[69]

Valve, which operates the Steam digital storefront for games on personal computers, also takes steps to remove games that are clearly copyright-infringing clones of other titles on the service, once notified of the issue.[100]

References

- Chen, Brian X. (March 11, 2012). "For Creators of Games, a Faint Line on Cloning". The New York Times. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- "Hunt for Grand Theft Auto pirates". BBC News. 2004-10-21. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- Calixto, Joshua (April 20, 2016). "The False Legacy Of Grand Theft Auto 3". Killscreen. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- Webster, Andrew (2009-12-06). "Cloning or theft? Ars explores game design with Jenova Chen". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2015-10-20.

- Kelly, Tadhg (2014-01-05). "Why all the Clones". TechCrunch. Retrieved 2015-10-20.

- Kent, Steven (2001). "The Jackals". Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- Ford, William (2012). "Copy Game for High Score: The First Video Game Lawsuit". Journal of Intellectual Property Law. 20 (1): 1–42. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- "Meet the video games godfather: Ralph Baer". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- Smith, Alexander (2015-11-16). "1TL200: A Magnavox Odyssey". They Create Worlds. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-04-25.

- US patent RE28,507, Rouch, William, "Television gaming apparatus", issued August 5, 1975

- US patent 3,659,285, Baer, Ralph; William Rouch & William Harrison, "Television gaming apparatus and method", issued April 25, 1972

- US patent 3,728,480, Baer, Ralph, "Television gaming and training apparatus", issued April 17, 1973

- "Magnavox Game Suit". Weekly Television Digest, with Consumer Electronics. December 13, 1976. p. 13.

- Kent, Steven (2001). "The King and Court". Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- Kent, Steven (2001). "And Then There Was Pong". Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 45–48. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- "Magnavox Patent". The New York Times. 1982-10-08. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- "Magnavox Settles Its Mattel Suit". The New York Times. 1983-02-16. Archived from the original on 2016-03-13. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- Mullis, Steve (2014-12-08). "Inventor Ralph Baer, The 'Father Of Video Games,' Dies At 92". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 2016-03-22. Retrieved 2016-05-03.

- Clark, Pamela (December 1982). "The Play's the Thing". BYTE. p. 6. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Herman, Leonard (2012). "Ball-and-Paddle Controllers". In Wolf, Mark J.P. (ed.). Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0814337226.

- Jensen, K. Thor (August 8, 2016). "8 Super Weird Bootleg Game Consoles". PC Magazine. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- Plunkett, Luke (November 4, 2011). "The Wonderful, Shady World of Knock-Off Nintendo Consoles". Kotaku. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- Jou, Eric (February 5, 2014). "A Brief History of Chinese Game Consoles". Kotaku. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- Rubens, Alex (August 15, 2013). "The Creation Of Missile Command And The Haunting Of Its Creator, Dave Theurer". Polygon. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- Williams, Gregg (December 1981). "Battle of the Asteroids". BYTE. pp. 163–165. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- "Atari Software / Piracy: This Game is Over". BYTE (advertisement). October 1981. p. 347. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Nelson, Mark. "Breaking Down Breakout: System And Level Design For Breakout-style Games". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- Patterson, Eric L. (November 3, 2011). "EGM Feature: The 5 Most Influential Japanese Games Day Four: Street Fighter II". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- "How hackers reinvented Street Fighter 2". Eurogamer.net. 21 February 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- Scott Patterson. "Innovation Has Never Been the Cornerstone of the Video Game Industry". Kotaku. Gawker Media. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- Parrish, Jeremy. "When SCUMM Ruled the Earth". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on February 29, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- Turner, Benjamin & Bowen, Kevin, Bringin' in the DOOM Clones, GameSpy, December 11, 2003, Accessed February 19, 2009

- Parkin, Simon (2013-06-07). "Don't Stop: The Game That Conquered Smartphones". New Yorker. Retrieved 2015-10-20.

- Fillari, Alessandro (May 26, 2018). "Battle Royale Games Explained". GameSpot. Archived from the original on May 26, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- Gilroy, Joab. "An Introduction to Auto Chess, Teamfight Tactics and Dota Underlords". IGN. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- Grayson, Nathan. "A Guide To Auto Chess, 2019's Most Popular New Game Genre". Kotaku. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- Schramm, Mike (May 15, 2013). "FreeCiv now playable in browsers, including on iOS devices". Engadget. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- Carpenter, Nicole (2019-07-16). "Gamers with godlike reflexes are racing to break world records in this rhythm game". PC Gamer. Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- Stubbs, Mike (May 1, 2018). "The spirit of Guitar Hero lives on in a bizarre community-made clone". Eurogamer. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- Etherington, Darrell (December 6, 2016). "Arago's AI can now beat some human players at complex civ strategy games". TechCrunch. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- Chalk, Andy (July 31, 2018). "EA takes down open source SimCity 2000 remake for using copyrighted assets". PC Gamer. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- Phillips, Tom (2015). ""Don't clone my indie game, bro": Informal cultures of videogame regulation in the independent sector". Cultural Trends. 24 (2): 143–153. doi:10.1080/09548963.2015.1031480. S2CID 145650507.

- Glasser, AJ (2011-07-27). "Clone Wars: What Copycats Really Do To The Social Games Industry". Adweek. Retrieved 2015-10-20.

- Tassi, Paul. "Over Sixty 'Flappy Bird' Clones Hit Apple's App Store Every Single Day".

- Batchlor, James (2014-08-21). "Flappy Bird creator's new game Swing Copters has already been cloned. A lot". Develop. Retrieved 2014-08-21.

- Rigny, Ryan (2014-03-05). "How to Make a No. 1 App With $99 and Three Hours of Work". Wired. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- Renaudin, Clement (2014-03-27). "Cloned to Death: Developers Release all 570 Emails That Discussed the Development of 'Threes!'". Touch Arcade. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- "THREES - A tiny puzzle that grows on you". asherv.com.

- Takahashi, Dean (January 31, 2012). "Zynga CEO: We aren't the copycats on Bingo social game". Venture Beat. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- Graft, Kris (January 31, 2012). "Talking Copycats with Zynga's Design Chief". Gamasutra. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- Messner, Steven (May 23, 2019). "Censorship, Steam, and the explosive rise of PC gaming in China". PC Gamer. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- Snyder, Matt (May 17, 2018). "China's Digital Game Sector" (PDF). United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- Goh, Brenda; Jiang, Sijia (May 7, 2019). "Tencent pulls blockbuster game PUBG in China, launches patriotic alternative". Reuters. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- Parkin, Simon (2011-12-23). "Clone Wars: is plagiarism killing creativity in the games industry?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- Lampros, Nicholas M. (2013). "Leveling Pains: Clone Gaming and the Changing Dynamics of an Industry". Berkeley Technology Law Journal. 28: 743.

- "U.S. Copyright Office – Games". United States Copyright Office. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- McArthur, Stephen (2013-02-27). "Clone Wars: The Six Most Important Cases Every Game Developer Should Know". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- Ibrahim, Mona (2009-12-09). "Analysis: Clone Games & Fan Games – Legal Issues". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- Kohler, Chris (August 14, 2018). "In Defense of ROMs, A Solution To Dying Games And Broken Copyright Laws". Kotaku. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- Lunsford, Christopher (Fall 2013). "Drawing a Line between Idea and Expression in Videogame Copyright: The Evolution of Substantial Similarity for Videogame Clones". Intellectual Property Law Bulletin. 18 (1): 87–118.

- Dean, Drew S. (2015). "Hitting reset: devising a new video game copyright regime". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 164: 1239.

- Casillas, Brian (2012). "Attack of the Clones: Copyright Protection for Video Game Developers". Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review. 33: 138.

- Orland, Kyle (2012-06-20). "Defining Tetris: How courts judge gaming clones". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- Jack C. Schecter (2012-06-18). "Grand Theft Video: Judge Gives Gamemakers Hope for Combating Clones". sunsteinlaw.com. Archived from the original on 2012-11-09. Retrieved 2012-06-19.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Kuehl, John (2016). "Video Games and Intellectual Property: Similarities, Differences, and a New Approach to Protection". Cybaris Intellectual Property Law Review. 7 (2): 4.

- Quagliariello, John (2019). "Applying Copyright Law to Videogames: Litigation Strategies for Lawyers". Harvard Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law. 10: 263.

- Methenitis, Mike (2015). "Laws of the Game". In Conway, Steven; deWinter, Jennifer (eds.). Video Game Policy: Production, Distribution, and Consumption. Routledge. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-1317607236.

- Boyd, S. Gregory (November 11, 2005). "Nintendo Entertainment System - Expired Patents Do Not Mean Expired Protection". Gamasutra. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- Batchelor, James (2014-09-05). "Experts explain difficulties in policing mobile marketplaces". Develop. Retrieved 2014-09-05.

- Kuchera, Ben (2008-03-09). "Patents on video game mechanics to strangle innovation, fun". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2012-08-10.

- Adams, Earnst (2008-03-05). "The Designer's Notebook: Damn All Gameplay Patents!". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2012-08-10.

- Chang, Steve; Dannenberg, Ross (2007-01-19). "The Ten Most Important Video Game Patents". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2012-08-10.

- US patent 6200138

- Sirlin, David (2007-02-27). "The Trouble With Patents". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- "Case Analysis: Sega v. Fox". Patent Arcade. 2010-07-12. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- Karmali, Luke (2014-01-22). "Candy Crush Saga Dev Goes After The Banner Saga". IGN. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- Lobov, Kostyantyn (February 19, 2018). "How multimedia trade marks could kill cloned games". GamesIndustry.biz. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- Kohler, Chris (2012-08-08). "CourtVille: Why Unclear Laws Put EA v. Zynga Up for Grabs". Wired. Retrieved 2012-08-08.

- Bennett, Chris (1994-03-18). "Street Fighter II Vs. Fighter's History". Davis LLP. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- Oxford, Naida (2007-12-11). "Twenty Years of Whoop-Ass". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- Dannenberg, Ross (2005-08-29). "Case: Capcom v. Data East (N.D. Cal. 1994) [C]". Patent Arcade. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- Griffen, Daniel Nye (2012-08-06). "EA Sues Zynga, But Deeper Social Issues Threaten". Forbes. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- Brown, Nathan (2012-01-25). "How Zynga cloned its way to success". Edge. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- Jamison, Peter (2010-09-08). "FarmVillains". SF Weekly. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- Kelly, Tadhg (2012-08-04). "Zyngapocalypse Now (And What Comes Next?)". TechCrunch. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- Kelly, Tadhg (2009-12-18). "Zynga and the End of the Beginning". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- Tassi, Paul (2012-08-03). "Zynga Pokes a Giant: EA Files Lawsuit After The Ville Clones The Sims". Forbes. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- Cifaldi, Frank (2013-02-15). "EA and Zynga settle The Ville copycat case out of court". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- Li, Zihao (Spring 2019). "The Copyright Protection of Video Games from Reskinning in China - A Comparative Study on UK, US and China Approaches". Tsinghua China Law Review. 11 (2): 293–340.

- Grosheide, F. Willem; Roerdink, Herwin; Thomas, Karianne (2014). "Intellectual Property Protection for Video Games: A View from the European Union". Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology. 9 (1).

- Welch, Judith J.; Anderson, Wayne L. (1991–1992). "Copyright Protection of Computer Software in Japan". Computer/Law Journal. 11: 287–298.

- Doi, Teruo (April 1982). "The Scope of Copyright Protection against Unauthorized Copying - Japan's Experience and Problems - The Nineteenth Annual Jean Geiringer Memoral Lecture". Journal of the Copyright Society of the U.S.A. 29 (4): 367–394.

- Katoh, Masanobu (Fall 2002). "Intellectual Property and the Internet: A Japanese Perspective". University of Illinois Journal of Law, Technology & Policy. 2 (2): 333–360.

- Snyder, Matt (May 17, 2018). China's Digital Game Sector (PDF) (Report). United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- Morris, Emily Michiko (April 20, 2016). "The War Over Video Game Warriors". Comparative Law Prof Blog. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- Dredge, Stuart (2012-02-03). "Should Apple take more action against march of the iOS clones?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-08-10.

- Epsom, Rip (2011-12-11). "Can We Stop The Copycat Apps?". TechCrunch. Retrieved 2012-08-10.

- Constine, John (2012-02-03). "Apple Kicks Chart Topping Fakes Out Of App Store". TechCrunch. Retrieved 2012-08-10.

- Foresman, Chris (2012-09-04). "Apple now provides online tool to report App Store ripoffs". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

- Wilde, Tyler (September 26, 2017). "Valve removes 173 'spam' games from Steam, all published by one person". PC Gamer. Retrieved September 6, 2019.