Visual effects

Visual effects (sometimes abbreviated VFX) is the process by which imagery is created or manipulated outside the context of a live action shot in filmmaking and video production. The integration of live action footage and CG elements to create realistic imagery is called VFX.

VFX involves the integration of live action footage (special effects) and generated imagery (digital or optics, animals or creatures) which look realistic, but would be dangerous, expensive, impractical, time-consuming or impossible to capture on film. Visual effects using computer-generated imagery (CGI) have more recently become accessible to the independent filmmaker with the introduction of affordable and relatively easy-to-use animation and compositing software.

History of effects (special and visual)

Early Developments

In 1857, Oscar Rejlander created the world's first "special effects" image by combining different sections of 32 negatives into a single image, making a montaged combination print. In 1895, Alfred Clark created what is commonly accepted as the first-ever motion picture special effect. While filming a reenactment of the beheading of Mary, Queen of Scots, Clark instructed an actor to step up to the block in Mary's costume. As the executioner brought the axe above his head, Clark stopped the camera, had all of the actors freeze, and had the person playing Mary step off the set. He placed a Mary dummy in the actor's place, restarted filming, and allowed the executioner to bring the axe down, severing the dummy's head. Techniques like these would dominate the production of special effects for a century.[1]

It was not only the first use of trickery in cinema, it was also the first type of photographic trickery that was only possible in a motion picture, and referred to as the "stop trick". Georges Méliès, an early motion picture pioneer, accidentally discovered the same "stop trick."

According to Méliès, his camera jammed while filming a street scene in Paris. When he screened the film, he found that the "stop trick" had caused a truck to turn into a hearse, pedestrians to change direction, and men to turn into women. Méliès, the director of the Théâtre Robert-Houdin, was inspired to develop a series of more than 500 short films, between 1896 and 1913, in the process developing or inventing such techniques as multiple exposures, time-lapse photography, dissolves, and hand painted color.

Because of his ability to seemingly manipulate and transform reality with the cinematograph, the prolific Méliès is sometimes referred to as the "Cinemagician." His most famous film, Le Voyage dans la lune (1902), a whimsical parody of Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon, featured a combination of live action and animation, and also incorporated extensive miniature and matte painting work.

Modern Age

VFX today is heavily used in almost all movies produced. The highest-grossing film of all time, Avengers: Endgame (2019), used VFX extensively. Around ninety percent of the film utilised VFX and CGI. Other than films, television series and web series are also known to utilise VFX.[2]

Techniques used

- Special Effects: Special effects (often abbreviated as SFX, SPFX, F/X or simply FX) are illusions or visual tricks used in the theatre, film, television, video game and simulator industries to simulate the imagined events in a story or virtual world. Special effects are traditionally divided into the categories of mechanical effects and optical effects. With the emergence of digital film-making a distinction between special effects and visual effects has grown, with the latter referring to digital post-production while "special effects" referring to mechanical and optical effects. Mechanical effects (also called practical or physical effects) are usually accomplished during the live-action shooting. This includes the use of mechanized props, scenery, scale models, animatronics, pyrotechnics and atmospheric effects: creating physical wind, rain, fog, snow, clouds, making a car appear to drive by itself and blowing up a building, etc. Mechanical effects are also often incorporated into set design and makeup. For example, prosthetic makeup can be used to make an actor look like a non-human creature. Optical effects (also called photographic effects) are techniques in which images or film frames are created photographically, either "in-camera" using multiple exposure, mattes or the Schüfftan process or in post-production using an optical printer. An optical effect might be used to place actors or sets against a different background.

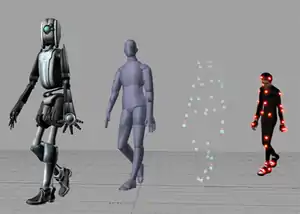

- Motion capture: Motion capture (sometimes referred as mo-cap or mocap, for short) is the process of recording the movement of objects or people. It is used in military, entertainment, sports, medical applications, and for validation of computer vision[3] and robotics.[4] In filmmaking and video game development, it refers to recording actions of human actors, and using that information to animate digital character models in 2D or 3D computer animation.[5][6][7] When it includes face and fingers or captures subtle expressions, it is often referred to as performance capture.[8] In many fields, motion capture is sometimes called motion tracking, but in filmmaking and games, motion tracking usually refers more to match moving.

- Matte painting: A matte painting is a painted representation of a landscape, set, or distant location that allows filmmakers to create the illusion of an environment that is not present at the filming location. Historically, matte painters and film technicians have used various techniques to combine a matte-painted image with live-action footage. At its best, depending on the skill levels of the artists and technicians, the effect is "seamless" and creates environments that would otherwise be impossible or expensive to film. In the scenes the painting part is static and movements are integrated on it.

- Animation: Animation is a method in which figures are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today, most animations are made with computer-generated imagery (CGI). Computer animation can be very detailed 3D animation, while 2D computer animation can be used for stylistic reasons, low bandwidth or faster real-time renderings. Other common animation methods apply a stop motion technique to two and three-dimensional objects like paper cutouts, puppets or clay figures. Commonly the effect of animation is achieved by a rapid succession of sequential images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon and beta movement, but the exact causes are still uncertain. Analog mechanical animation media that rely on the rapid display of sequential images include the phénakisticope, zoetrope, flip book, praxinoscope and film. Television and video are popular electronic animation media that originally were analog and now operate digitally. For display on the computer, techniques like animated GIF and Flash animation were developed.

- 3D modeling: In 3D computer graphics, 3D modeling is the process of developing a mathematical representation of any surface of an object (either inanimate or living) in three dimensions via specialized software. The product is called a 3D model. Someone who works with 3D models may be referred to as a 3D artist. It can be displayed as a two-dimensional image through a process called 3D rendering or used in a computer simulation of physical phenomena. The model can also be physically created using 3D printing devices.

- Rigging: Skeletal animation or rigging is a technique in computer animation in which a character (or other articulated object) is represented in two parts: a surface representation used to draw the character (called the mesh or skin) and a hierarchical set of interconnected parts (called bones, and collectively forming the skeleton or rig), a virtual armature used to animate (pose and keyframe) the mesh.[9] While this technique is often used to animate humans and other organic figures, it only serves to make the animation process more intuitive, and the same technique can be used to control the deformation of any object—such as a door, a spoon, a building, or a galaxy. When the animated object is more general than, for example, a humanoid character, the set of "bones" may not be hierarchical or interconnected, but simply represent a higher-level description of the motion of the part of mesh it is influencing.

- Rotoscoping: Rotoscoping is an animation technique that animators use to trace over motion picture footage, frame by frame, to produce realistic action. Originally, animators projected photographed live-action movie images onto a glass panel and traced over the image. This projection equipment is referred to as a rotoscope, developed by Polish-American animator Max Fleischer. This device was eventually replaced by computers, but the process is still called rotoscoping. In the visual effects industry, rotoscoping is the technique of manually creating a matte for an element on a live-action plate so it may be composited over another background.[10][11] Chroma key is more often used for this, as it is faster and requires less work, however rotoscopy is still used on subjects that aren't in front of a green (or blue) screen, due to practical or economic reasons.

- Match Moving: In visual effects, match moving is a technique that allows the insertion of computer graphics into live-action footage with correct position, scale, orientation, and motion relative to the photographed objects in the shot. The term is used loosely to describe several different methods of extracting camera motion information from a motion picture. Sometimes referred to as motion tracking or camera solving, match moving is related to rotoscoping and photogrammetry. Match moving is sometimes confused with motion capture, which records the motion of objects, often human actors, rather than the camera. Typically, motion capture requires special cameras and sensors and a controlled environment (although recent developments such as the Kinect camera and Apple's Face ID have begun to change this). Match moving is also distinct from motion control photography, which uses mechanical hardware to execute multiple identical camera moves. Match moving, by contrast, is typically a software-based technology, applied after the fact to normal footage recorded in uncontrolled environments with an ordinary camera. Match moving is primarily used to track the movement of a camera through a shot so that an identical virtual camera move can be reproduced in a 3D animation program. When new animated elements are composited back into the original live-action shot, they will appear in perfectly matched perspective and therefore appear seamless.

- Compositing: Compositing is the combining of visual elements from separate sources into single images, often to create the illusion that all those elements are parts of the same scene. Live-action shooting for compositing is variously called "chroma key", "blue screen", "green screen" and other names. Today, most, though not all, compositing is achieved through digital image manipulation. Pre-digital compositing techniques, however, go back as far as the trick films of Georges Méliès in the late 19th century, and some are still in use.

Production Pipeline

Visual effects are often integral to a movie's story and appeal. Although most visual effects work is completed during post-production, it usually must be carefully planned and choreographed in pre-production and production. While special effects such as explosions and car chases are made on set, visual effects are primarily executed in post-production with the use of multiple tools and technologies such as graphic design, modeling, animation and similar software. A visual effects supervisor is usually involved with the production from an early stage to work closely with production and the film's director design, guide and lead the teams required to achieve the desired effects.

Many studios are specialized in the field of visual effects areas, among which: Digital Domain, DreamWorks Animation, Framestore, Weta Digital, Industrial Light & Magic, Pixomondo and Moving Picture Company.

VFX Industry

The VFX and Animation studios are scattered all over the world; studios are located in California, Vancouver, London, Paris, New Zealand, Mumbai, Bangalore, Sydney, Tokyo, Hyderabad and Shanghai.[12]

List of visual effects companies

- 4th Creative Party (Korea)

- The Aaron Sims Company (Los Angeles, United States)

- Adobe Systems Incorporated (San Jose, United States)

- Animal Logic (Sydney, AU and Venice, United States)

- Atmosphere Visual Effects (Vancouver, Canada)

- Base FX (Beijing; Wuxi; Xiamen; Kuala Lumpur; Los Angeles, United States)

- Bird Studios (London, England)

- BUF Compagnie (Paris, France)

- Cafe FX (Santa Maria, United States)

- Cinema Research Corporation, 1954–2000 (Hollywood, United States)

- Cinesite (London/Hollywood)

- Creature Effects, Inc. (Los Angeles, United States)

- Digital Domain (Playa Vista, United States)

- Double Negative (VFX) (London, England)

- DreamWorks (Los Angeles, United States)

- The Embassy Visual Effects (Vancouver, Canada)

- Escape Studios (London, England)

- Flash Film Works (Los Angeles, United States)

- Framestore (London, England)

- Giantsteps (Venice, United States)

- Hydraulx (Santa Monica, United States)

- Image Engine (Vancouver, Canada)

- Industrial Light & Magic (San Francisco, United States), founded by George Lucas

- Intelligent Creatures (Toronto, Canada)

- Jim Henson's Creature Shop, (Los Angeles; Hollywood; Camden Town, London)

- Legacy Effects, (Los Angeles, United States)

- Lola Visual Effects (Los Angeles, United States)

- Look Effects (Culver City, United States)

- M5 Industries (San Francisco, United States)

- Mac Guff (Los Angeles; Paris)

- Manex Visual Effects (Alameda, United States)

- Main Road Post (Moscow, Russia)

- Makuta VFX (Universal City, United States) (Hyderabad, India)

- Matte World Digital (Novato, United States)

- Method Studios (Los Angeles; New York; Vancouver, Canada)

- Meteor Studios (Canada)

- Mikros Image (Paris, Montreal, Bruxelles, Liège)

- The Mill (London; NY and LA)

- Modus FX (Montreal, Canada)

- Moving Picture Company (Soho, London, England)

- Netter Digital (North Hollywood, United States)

- The Orphanage (California, United States)

- Pixomondo (Frankfurt; Munich; Stuttgart; Los Angeles; Beijing; Toronto; Baton Rouge, Los Angeles)

- Prana Studios (Los Angeles, United States)

- Rainmaker Digital Effects (Vancouver, Canada)

- Rhythm and Hues Studios (Los Angeles, United States)

- Red Visual Effects (London, United Kingdom)

- Rise FX (Berlin, Germany)

- Rising Sun Pictures (Adelaide, Australia)

- Robot Communications (Tokyo, Japan)

- Rodeo FX (Montreal, Quebec, Munich, Los Angeles)

- Scanline VFX (Munich, Los Angeles, Vancouver, Stuttgart, London, Montreal, Seoul)

- Snowmasters (Lexington, United States)

- Sony Pictures Imageworks (Culver City, United States)

- Strictly FX, live special effects company

- Surreal World (Melbourne, Australia)

- Tippett Studio (Berkeley, United States)

- Tsuburaya Productions (Tokyo, Japan)

- VisionArt (Santa Monica, United States)

- Vision Crew Unlimited

- Weta Digital (Wellington, New Zealand)

- ZERO VFX (Boston, United States)

- Zoic Studios (Culver City, United States)

- ZFX Inc, a flying effects company

- yFX studio (Mumbai, India)

The companies above may use their own software or use software such as Nuke, Blackmagic Fusion, Houdini (software), Autodesk Maya, Blender (software), Zbrush and Adobe After Effects, or other similar (in purpose) software packages.

See also

- Animation

- Match moving

- Bluescreen/greenscreen

- Compositing

- Computer-generated imagery

- Computer animation

- Front projection effect

- Interactive video compositing

- Live-action animated film

- Matte painting

- Physical effects, another category of special effects

- Optics#Visual effects

- Rear projection effect

- Special effects

- VFX Creative Director

- Visual Effects Society

References

- Rickitt, 10.

- https://www.vfxvoice.com/global-vfx-state-of-the-industry-2019/

- David Noonan, Peter Mountney, Daniel Elson, Ara Darzi and Guang-Zhong Yang. A Stereoscopic Fibroscope for Camera Motion and 3D Depth Recovery During Minimally Invasive Surgery. In proc ICRA 2009, pp. 4463–4468. <http://www.sciweavers.org/external.php?u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.doc.ic.ac.uk%2F%7Epmountne%2Fpublications%2FICRA%25202009.pdf&p=ieee>

- Yamane, Katsu, and Jessica Hodgins. "Simultaneous tracking and balancing of humanoid robots for imitating human motion capture data." Intelligent Robots and Systems, 2009. IROS 2009. IEEE/RSJ International Conference on. IEEE, 2009.

- NY Castings, Joe Gatt, Motion Capture Actors: Body Movement Tells the Story Archived 2014-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, Accessed June 21, 2014

- Andrew Harris Salomon, Feb. 22, 2013, Backstage Magazine, Growth In Performance Capture Helping Gaming Actors Weather Slump, Accessed June 21, 2014, "..But developments in motion-capture technology, as well as new gaming consoles expected from Sony and Microsoft within the year, indicate that this niche continues to be a growth area for actors. And for those who have thought about breaking in, the message is clear: Get busy...."

- Ben Child, 12 August 2011, The Guardian, Andy Serkis: why won't Oscars go ape over motion-capture acting? Star of Rise of the Planet of the Apes says performance capture is misunderstood and its actors deserve more respect, Accessed June 21, 2014

- Hugh Hart, January 24, 2012, Wired magazine, When will a motion capture actor win an Oscar?, Accessed June 21, 2014, "...the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ historic reluctance to honor motion-capture performances .. Serkis, garbed in a sensor-embedded Lycra body suit, quickly mastered the then-novel art and science of performance-capture acting. ..."

- Soriano, Marc. "Skeletal Animation". Bourns College of Engineering. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- Maçek III, J.C. (2012-08-02). "'American Pop'... Matters: Ron Thompson, the Illustrated Man Unsung". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 2013-08-24.

- "Through a 'Scanner' dazzlingly: Sci-fi brought to graphic life" USA TODAY, August 2, 2006 Wednesday, LIFE; Pg. 4D WebLink Archived 2011-12-23 at the Wayback Machine

- https://www.educba.com/vfx-companies/

Further reading

- The VES Handbook of Visual Effects: Industry Standard VFX Practices and Procedures, Jeffrey A. Okun & Susan Zwerman, Publisher: Focal Press 2010.

- T. Porter and T. Duff, "Compositing Digital Images", Proceedings of SIGGRAPH '84, 18 (1984).

- The Art and Science of Digital Compositing (ISBN 0-12-133960-2)

- McClean, Shilo T. (2007). Digital Storytelling: The Narrative Power of Visual Effects in Film. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-13465-1.

- Mark Cotta Vaz; Craig Barron: The Invisible Art: The Legends of Movie Matte Painting. San Francisco, Cal.: Chronicle Books, 2002; ISBN 0-8118-3136-1

- Peter Ellenshaw; Ellenshaw Under Glass – Going to the Matte for Disney

- Richard Rickitt: Special Effects: The History and Technique. Billboard Books; 2nd edition, 2007; ISBN 0-8230-8408-6.

- Patel, Mayur (2009). The Digital Visual Effects Studio: The Artists and Their Work Revealed. ISBN 978-1-4486-6547-1.

External links

- Take Five Minutes to Watch 100 Years of Visual Effects by Rosa Golijan – Gizmodo.com – August 27, 2009