Traditional animation

Traditional animation (or classical animation, cel animation, hand-drawn animation, 2D animation or just 2D) is an animation technique in which each frame is drawn by hand. The technique was the dominant form of animation in cinema until the advent of computer animation.

Process

Animation production usually begins after a story is conceived. The oral or literary source material must then be converted into an animation film script, from which the storyboard is derived. The storyboard has an appearance somewhat similar to comic book panels, and is a shot by shot breakdown of the staging, acting and any camera moves that will be present in the film. The images allow the animation team to plan the flow of the plot and the composition of the imagery. The storyboard artists will have regular meetings with the director and may have to redraw or "re-board" a sequence many times before it meets final approval.

Voice recording

Before true animation begins, a preliminary soundtrack or scratch track is recorded, so that the animation may be more precisely synchronized to the soundtrack. Given the slow, methodical manner in which traditional animation is produced, it is almost always easier to synchronize animation to a pre-existing soundtrack than it is to synchronize a soundtrack to pre-existing animation. A completed cartoon soundtrack will feature music, sound effects, and dialogue performed by voice actors. However, the scratch track used during animation typically contains only the voices, any vocal songs to which characters must sing-along, and temporary musical score tracks; the final score and sound effects are added during post-production.

In the case of Japanese anime, as well as most pre-1930 sound animated cartoons, the sound was post-synched; that is, the soundtrack was recorded after the film elements were finished by watching the film and performing the dialogue, music, and sound effects required. Some studios, most notably Fleischer Studios, continued to post-synch their cartoons through most of the 1930s, which allowed for the presence of the "muttered ad-libs" present in many Popeye the Sailor and Betty Boop cartoons.

Animatic

Usually, an animatic or story reel is created after the soundtrack is recorded, but before full animation begins. An animatic typically consists of pictures of the storyboard timed and cut together with the soundrack. This allows the animators and directors to work out any script and timing issues that may exist with the current storyboard. The storyboard and soundtrack are amended if necessary, and a new animatic may be created and reviewed with the director until the storyboard is perfected. Editing the film at the animatic stage prevents the animation of scenes that would be edited out of the film; as traditional animation is a very expensive and time-consuming process, creating scenes that will eventually be edited out of the completed cartoon is strictly avoided.

Advertising agencies today employ the use of animatics to test their commercials before they are made into full up spots. Animatics use drawn artwork, with moving pieces (for example, an arm that reaches for a product, or a head that turns). Video storyboards are similar to animatics but do not have moving pieces. Photomatics is another option when creating test spots, but instead of using drawn artwork, there is a shoot in which hundreds of digital photographs are taken. The large number of images to choose from may make the process of creating a test commercial a bit easier, as opposed to creating an animatic, because changes to drawn art take time and money. Photomatics generally cost more than animatics, as they may require a shoot and on-camera talent. However, the emergence of affordable stock photography and image editing software permits the inexpensive creation of photomatics using stock elements and photo composites.

Design and timing

The storyboards are then sent to the design departments. Character designers prepare model sheets for any characters and props that appear in the film; and these are used to help standardize appearance, poses, and gestures. The model sheets will often include "turnarounds" which show how a character or object looks in three-dimensions along with standardized special poses and expressions so that the artists working on the project can have a guide to refer to in order to deliver consistent work. Sometimes, small statues known as maquettes may be produced, so that an animator can see what a character looks like in three dimensions. Around the same time, the background stylists will do similar work for any settings and locations present in the storyboard, and the art directors and color stylists will determine the art style and color schemes to be used.

While the design is going on, the timing director (who in many cases will be the main director) takes the animatic and analyzes exactly what poses drawings, and lip movements will be needed on what frames. An exposure sheet (or X-sheet for short) is created; this is a printed table that breaks down the action, dialogue, and sound frame-by-frame as a guide for the animators. If a film is based more strongly in music, a bar sheet may be prepared in addition to or instead of an X-sheet.[1] Bar sheets show the relationship between the on-screen action, the dialogue, and the actual musical notation used in the score.

Layout

Layout begins after the designs are completed and approved by the director. The layout process is the same as the blocking out of shots by a cinematographer on a live-action film. It is here that the background layout artists determine the camera angles, camera paths, lighting, and shading of the scene. Character layout artists will determine the major poses for the characters in the scene and will make a drawing to indicate each pose. For short films, character layouts are often the responsibility of the director.

The layout drawings and storyboards are then spliced, along with the audio and an animatic is formed (not to be confused with its predecessor, the leica reel). The term "animatic" was originally coined by Walt Disney Animation Studios.

Animation

Once the animatic is finally approved by the director, animation begins.

In the traditional animation process, animators will begin by drawing sequences of animation on sheets of transparent paper perforated to fit the peg bars in their desks, often using colored pencils, one picture or "frame" at a time.[2] A peg bar is an animation tool used in traditional (cel) animation to keep the drawings in place. The pins in the peg bar match the holes in the paper. It is attached to the animation desk or light table, depending on which is being used. A key animator or lead animator will draw the key drawings in a scene, using the character layouts as a guide. The key animator draws enough of the frames to get across the major poses within a character performance; in a sequence of a character jumping across a gap, the key animator may draw a frame of the character as he is about to leap, two or more frames as the character is flying through the air and the frame for the character landing on the other side of the gap.

Timing is important for the animators drawing these frames; each frame must match exactly what is going on in the soundtrack at the moment the frame will appear, or else the discrepancy between sound and visual will be distracting to the audience. For example, in high-budget productions, extensive effort is given in making sure a speaking character's mouth matches in shape the sound that the character's actor is producing as he or she speaks.

While working on a scene, a key animator will usually prepare a pencil test of the scene. A pencil test is a much rougher version of the final animated scene (often devoid of many character details and color); the pencil drawings are quickly photographed or scanned and synced with the necessary soundtracks. This allows the animation to be reviewed and improved upon before passing the work on to his assistant animators, who will add details and some of the missing frames in the scene. The work of the assistant animators is reviewed, pencil-tested, and corrected until the lead animator is ready to meet with the director and have his scene sweatboxed, or reviewed by the director, producer, and other key creative team members. Similar to the storyboarding stage, an animator may be required to redo a scene many times before the director will approve it.

In high-budget animated productions, often each major character will have an animator or group of animators solely dedicated to drawing that character. The group will be made up of one supervising animator, a small group of key animators, and a larger group of assistant animators. For scenes where two characters interact, the key animators for both characters will decide which character is "leading" the scene, and that character will be drawn first. The second character will be animated to react to and support the actions of the "leading" character.

Once the key animation is approved, the lead animator forwards the scene on to the clean-up department, made up of the clean-up animators and the inbetweeners. The clean-up animators take the lead and assistant animators' drawings and trace them onto a new sheet of paper, making sure to include all of the details present on the original model sheets, so that the film maintains a cohesiveness and consistency in art style. The inbetweeners will draw in whatever frames are still missing in-between the other animators' drawings. This procedure is called tweening. The resulting drawings are again pencil-tested and sweatboxed until they meet approval.

At each stage during pencil animation, approved artwork is spliced into the Leica reel.[3]

This process is the same for both character animation and special effects animation, which on most high-budget productions are done in separate departments. Effects animators animate anything that moves and are not a character, including props, vehicles, machinery and phenomena such as fire, rain, and explosions. Sometimes, instead of drawings, a number of special processes are used to produce special effects in animated films; rain, for example, has been created in Disney animated films since the late 1930s by filming slow-motion footage of water in front of a black background, with the resulting film superimposed over the animation.

Pencil test

After all the drawings are cleaned up, they are then photographed on an animation camera, usually on black and white film stock.[4] Nowadays, pencil tests can be made using a video camera and computer software.

Backgrounds

While the animation is being done, the background artists will paint the sets over which the action of each animated sequence will take place. These backgrounds are generally done in gouache or acrylic paint, although some animated productions have used backgrounds done in watercolor or oil paint. Background artists follow very closely the work of the background layout artists and color stylists (which is usually compiled into a workbook for their use) so that the resulting backgrounds are harmonious in tone with the character designs.

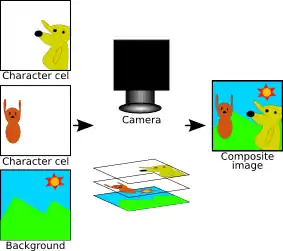

Traditional ink-and-paint and camera

Once the clean-ups and in-between drawings for a sequence are completed, they are prepared for photography, a process known as ink-and-paint. Each drawing is then transferred from paper to a thin, clear sheet of plastic called a cel, a contraction of the material name celluloid (the original flammable cellulose nitrate was later replaced with the more stable cellulose acetate). The outline of the drawing is inked or photocopied onto the cel, and gouache, acrylic or a similar type of paint is used on the reverse sides of the cels to add colors in the appropriate shades. In many cases, characters will have more than one color palette assigned to them; the usage of each one depends upon the mood and lighting of each scene. The transparent quality of the cel allows for each character or object in a frame to be animated on different cels, as the cel of one character can be seen underneath the cel of another; and the opaque background will be seen beneath all of the cels.

When an entire sequence has been transferred to cels, the photography process begins. Each cel involved in a frame of a sequence is laid on top of each other, with the background at the bottom of the stack. A piece of glass is lowered onto the artwork in order to flatten any irregularities, and the composite image is then photographed by a special animation camera, also called rostrum camera.[5] The cels are removed, and the process repeats for the next frame until each frame in the sequence has been photographed. Each cel has registration holes, small holes along the top or bottom edge of the cel, which allow the cel to be placed on corresponding peg bars[6] before the camera to ensure that each cel aligns with the one before it; if the cels are not aligned in such a manner, the animation, when played at full speed, will appear "jittery." Sometimes, frames may need to be photographed more than once, in order to implement superimpositions and other camera effects. Pans are created by either moving the cels or backgrounds 1 step at a time over a succession of frames (the camera does not pan; it only zooms in and out).

Dope sheets are created by the animators and used by the camera operator to transfer each animation drawing into the number of film frames specified by the animators, whether it is 1 (1s, ones) 2 (2s, twos) or 3 (3s, threes).

As the scenes come out of final photography, they are spliced into the Leica reel, taking the place of the pencil animation. Once every sequence in the production has been photographed, the final film is sent for development and processing, while the final music and sound effects are added to the soundtrack. Again, editing in the traditional live-action sense is generally not done in animation, but if it is required it is done at this time, before the final print of the film is ready for duplication or broadcast.

Among the most common types of animation rostrum cameras was the Oxberry. Such cameras were always made of black anodized aluminum, and commonly had 2 peg bars, 1 at the top and 1 at the bottom of the lightbox. The Oxberry Master Series had 4 peg bars, 2 above and 2 below, and sometimes used a "floating peg bar" as well. The height of the column on which the camera was mounted determined the amount of zoom achievable on a piece of artwork. Such cameras were massive mechanical affairs that might weigh close to a ton and take hours to break down or set up.

In the later years of the animation rostrum camera, stepper motors controlled by computers were attached to the various axes of movement of the camera, thus saving many hours of hand cranking by human operators. Gradually, motion control techniques were adopted throughout the industry.

Digital ink and paint processes gradually made these traditional animation techniques and equipment obsolete.

Digital ink and paint

The current process, termed "digital ink and paint", is the same as traditional ink and paint until after the animation drawings are completed;[7] instead of being transferred to cels, the animators' drawings are either scanned into a computer or drawn directly onto a computer monitor via graphics tablets (such as a Wacom Cintiq tablet), where they are colored and processed using one or more of a variety of software packages. The resulting drawings are composited in the computer over their respective backgrounds, which have also been scanned into the computer (if not digitally painted), and the computer outputs the final film by either exporting a digital video file, using a video cassette recorder or printing to film using a high-resolution output device. Use of computers allows for easier exchange of artwork between departments, studios, and even countries and continents (in most low-budget American animated productions, the bulk of the animation is actually done by animators working in other countries, including South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, China, Singapore, Mexico, India, and the Philippines). As the cost of both inking and painting new cels for animated films and TV programs and the repeated usage of older cels for newer animated TV programs and films went up and the cost of doing the same thing digitally went down, eventually, the digital ink-and-paint process became the standard for future animated movies and TV programs.

Hanna-Barbera was the first American animation studio to implement a computer animation system for digital ink-and-paint usage.[8] Following a commitment to the technology in 1979, computer scientist Marc Levoy led the Hanna-Barbera Animation Laboratory from 1980 to 1983, developing an ink-and-paint system that was used in roughly a third of Hanna-Barbera's domestic production, starting in 1984 and continuing until replaced with third-party software in 1996.[8][9] In addition to a cost savings compared to traditional cel painting of 5 to 1, the Hanna-Barbera system also allowed for multiplane camera effects evident in H-B productions such as A Pup Named Scooby-Doo (1988).[10]

Digital ink and paint has been in use at Walt Disney Animation Studios since 1989, where it was used for the final rainbow shot in The Little Mermaid. All subsequent Disney animated features were digitally inked-and-painted (starting with The Rescuers Down Under, which was also the first major feature film to entirely use digital ink and paint), using Disney's proprietary CAPS (Computer Animation Production System) technology, developed primarily by Pixar Animation Studios. The CAPS system allowed the Disney artists to make use of colored ink-line techniques mostly lost during the xerography era, as well as multiplane effects, blended shading, and easier integration with 3D CGI backgrounds (as in the ballroom sequence in the 1991 film Beauty and the Beast), props, and characters.[11] [12]

While Hanna-Barbera and Disney began implementing digital inking and painting, it took the rest of the industry longer to adapt. Many filmmakers and studios did not want to shift to the digital ink-and-paint process because they felt that the digitally-colored animation would look too synthetic and would lose the aesthetic appeal of the non-computerized cel for their projects. Many animated television series were still animated in other countries by using the traditionally inked-and-painted cel process as late as 2004, though most of them switched over to the digital process at some point during their run. The last major feature film to use traditional ink and paint was Satoshi Kon's Millennium Actress (2001); the last major animation productions in the west to use the traditional process was Cartoon Network's Ed, Edd n Eddy and The Simpsons, which switched to digital paint in 2004 and 2002 respectively,[13] while the last major animated production overall to abandon cel animation was the television adaptation of Sazae-san, which remained stalwart with the technique until September 29, 2013, when it switched to fully digital animation on October 6, 2013. Prior to this, the series adopted digital animation solely for its opening credits in 2009, but retained the use of traditional cels for the main content of each episode.[14] Minor productions, such as Hair High (2004) by Bill Plympton, have used traditional cels long after the introduction of digital techniques. Most studios today use one of a number of other high-end software packages, such as Toon Boom Harmony, Toonz Bravo!, Animo, and RETAS, or even consumer-level applications such as Adobe Flash, Toon Boom Technologies, TVPaint, and Toonz Harlequin.

Computers and digital video cameras

Computers and digital video cameras can also be used as tools in traditional cel animation without affecting the film directly, assisting the animators in their work and making the whole process faster and easier. Doing the layouts on a computer is much more effective than doing it by traditional methods.[15] Additionally, video cameras give the opportunity to see a "preview" of the scenes and how they will look when finished, enabling the animators to correct and improve upon them without having to complete them first. This can be considered a digital form of pencil testing.

Techniques

Cels

The cel is an important innovation to traditional animation, as it allows some parts of each frame to be repeated from frame to frame, thus saving labor. A simple example would be a scene with two characters on screen, one of which is talking and the other standing silently. Since the latter character is not moving, it can be displayed in this scene using only one drawing, on one cel, while multiple drawings on multiple cels are used to animate the speaking character.

For a more complex example, consider a sequence in which a boy sets a plate upon a table. The table stays still for the entire sequence, so it can be drawn as part of the background. The plate can be drawn along with the character as the character places it on the table. However, after the plate is on the table, the plate no longer moves, although the boy continues to move as he draws his arm away from the plate. In this example, after the boy puts the plate down, the plate can then be drawn on a separate cel from the boy. Further frames feature new cels of the boy, but the plate does not have to be redrawn as it is not moving; the same cel of the plate can be used in each remaining frame that it is still upon the table. The cel paints were actually manufactured in shaded versions of each color to compensate for the extra layer of cel added between the image and the camera; in this example, the still plate would be painted slightly brighter to compensate for being moved one layer down. In TV and other low-budget productions, cels were often "cycled" (i.e., a sequence of cels was repeated several times), and even archived and reused in other episodes. After the film was completed, the cels were either thrown out or, especially in the early days of animation, washed clean and reused for the next film. In some cases, some of the cels were put into the "archive" to be used again and again for future purposes in order to save money. Some studios saved a portion of the cels and either sold them in studio stores or presented them as gifts to visitors.

In very early cartoons made before the use of the cel, such as Gertie the Dinosaur (1914), the entire frame, including the background and all characters and items, were drawn on a single sheet of paper, then photographed. Everything had to be redrawn for each frame containing movements. This led to a "jittery" appearance; imagine seeing a sequence of drawings of a mountain, each one slightly different from the one preceding it. The pre-cel animation was later improved by using techniques like the slash and tear system invented by Raoul Barre; the background and the animated objects were drawn on separate papers.[16] A frame was made by removing all the blank parts of the papers where the objects were drawn before being placed on top of the backgrounds and finally photographed. The cel animation process was invented by Earl Hurd and John Bray in 1915.

Limited animation

In lower-budget productions, shortcuts available through the cel technique are used extensively. For example, in a scene in which a man is sitting in a chair and talking, the chair and the body of the man may be the same in every frame; only his head is redrawn, or perhaps even his head stays the same while only his mouth moves. This is known as limited animation.[17] The process was popularized in theatrical cartoons by United Productions of America and used in most television animation, especially that of Hanna-Barbera. The end result does not look very lifelike, but is inexpensive to produce, and therefore allows cartoons to be made on small television budgets.

"Shooting on twos"

Moving characters are often shot "on twos", that is to say, one drawing is shown for every two frames of film (which usually runs at 24 frames per second), meaning there are only 12 drawings per second.[18] Even though the image update rate is low, the fluidity is satisfactory for most subjects. However, when a character is required to perform a quick movement, it is usually necessary to revert to animating "on ones", as "twos" are too slow to convey the motion adequately. A blend of the two techniques keeps the eye fooled without unnecessary production costs.

Academy Award-nominated animator Bill Plympton is noted for his style of animation that uses very few in-betweens and sequences that are done on 3s or on 4s, holding each drawing on the screen from 1/8 to 1/6 of a second.[19] While Plympton uses near-constant three-frame holds, sometimes animation that simply averages eight drawings per second is also termed "on threes" and is usually done to meet budget constraints, along with other cost-cutting measures like holding the same drawing of a character for a prolonged time or panning over a still image,[20] techniques often used in low-budget TV productions.[21] It is also common in anime, where fluidity is sacrificed in lieu of a shift towards complexity in the designs and shading (in contrast with the more functional and optimized designs in the Western tradition); even high-budget theatrical features such as Studio Ghibli's employ the full range: from smooth animation "on ones" in selected shots (usually quick action accents) to common animation "on threes" for regular dialogue and slow-paced shots.

Animation loops

Creating animation loops or animation cycles is a labor-saving technique for animating repetitive motions, such as a character walking or a breeze blowing through the trees. In the case of walking, the character is animated taking a step with its right foot, then a step with its left foot. The loop is created so that, when the sequence repeats, the motion is seamless. However, because an animation loop essentially uses the same bit of animation over and over again, it is easily detected and can, in fact, become distracting to an audience. In general, they are used only sparingly by productions with moderate or high budgets.

Ryan Larkin's 1969 Academy Award-nominated National Film Board of Canada short Walking makes creative use of loops. In addition, a promotional music video from Cartoon Network's Groovies featuring the Soul Coughing song "Circles" poked fun at animation loops as they are often seen in The Flintstones, in which Fred and Barney (along with various Hanna-Barbera characters that aired on Cartoon Network), supposedly walking in a house, wonder why they keep passing the same table and vase over and over again.

Multiplane process

The multiplane process is a technique primarily used to give a sense of depth or parallax to two-dimensional animated films. To use this technique in traditional animation, the artwork is painted or placed onto separate layers called planes. These planes, typically constructed of panes of transparent glass or plexiglass, are then aligned and placed with specific distances between each plane.[22] The order in which the planes are placed, and the distance between them, is determined by what element of the scene is on the pane as well as the entire scene’s intended depth.[23] A camera, mounted above or in front of the panes, moves its focus toward or away from the planes during the capture of the individual animation frames. In some devices, the individual planes can be moved toward or away from the camera. This gives the viewer the impression that they are moving through the separate layers of art as though in a three-dimensional space.

History

Predecessors of this technique and the equipment used to implement it began appearing in the late 19th century. Painted glass panes were often used in matte shots and glass shots,[24] as seen in the work of Norman Dawn.[25] In 1923, Lotte Reiniger and her animation team constructed one of the first multiplane animation structures, a device called a Tricktisch. Its top-down, vertical design allowed for overhead adjusting of individual, stationary planes. The Tricktisch was used in the filming of The Adventures of Prince Achmed, one of Reiniger’s most well-known works.[26] Future multiplane animation devices would generally use the same vertical design as Reiniger’s device. One notable exception to this trend was the Setback Camera, developed and used by Fleischer Studios. This device used miniature three-dimensional models of sets, with animated cels placed at various positions within the set. This placement gave the appearance of objects moving in front of and behind the animated characters, and was often referred to as the Tabletop Method.[27]

The most famous device used for multiplane animation was the multiplane camera. This device, originally designed by former Walt Disney Studios animator/director Ub Iwerks, is a vertical, top-down camera crane that shot scenes painted on multiple, individually-adjustable glass planes.[22] The movable planes allowed for changeable depth within individual animated scenes.[22] In later years Disney Studios would adopt this technology for their own uses. Designed in 1937 by William Garity, the multiplane camera used for the film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs utilized artwork painted on up to seven separate, movable planes, as well as a vertical, top-down camera.[28]

The final animated film by Disney that featured the use of their multiplane camera was The Little Mermaid, though the work was outsourced as Disney’s equipment was inoperative at the time.[29] Usage of the multiplane camera or similar devices declined due to production costs and the rise of digital animation. Beginning largely with the use of CAPS, digital multiplane cameras would help streamline the process of adding layers and depth to animated scenes.

Impact

The spread and development of multiplane animation helped animators tackle problems with motion tracking and scene depth, and reduced production times and costs for animated works.[22] In a 1957 recording, Walt Disney explained why motion tracking was an issue for animators, as well as what multiplane animation could do to solve it. Using a two-dimensional still of an animated farmhouse at night, Disney demonstrated that zooming in on the scene, using traditional animation techniques of the time, increased the size of the moon. In real-life experience, the moon would not increase in size as a viewer approached a farmhouse. Multiplane animation solved this problem by separating the moon, farmhouse, and farmland into separate planes, with the moon being farthest away from the camera. To create the zoom effect, the first two planes were moved closer to the camera during filming, while the plane with the moon remained at its original distance.[30] This provided a depth and fullness to the scene that was closer in resemblance to real life, which was a prominent goal for many animation studios at the time.

Xerography

Applied to animation by Ub Iwerks at the Walt Disney studio during the late 1950s, the electrostatic copying technique called xerography allowed the drawings to be copied directly onto the cels, eliminating much of the "inking" portion of the ink-and-paint process.[31] This saved time and money, and it also made it possible to put in more details and to control the size of the xeroxed objects and characters (this replaced the little known, and seldom used, photographic lines technique at Disney, used to reduce the size of animation when needed). At first, it resulted in a more sketchy look, but the technique was improved upon over time.

Disney animator and engineer Bill Justice had patented a forerunner of the Xerox process in 1944, where drawings made with a special pencil would be transferred to a cel by pressure, and then fixing it. It is not known if the process was ever used in animation.[32]

The xerographic method was first tested by Disney in a few scenes of Sleeping Beauty and was first fully used in the short film Goliath II, while the first feature entirely using this process was One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961). The graphic style of this film was strongly influenced by the process. Some hand inking was still used together with xerography in this and subsequent films when distinct colored lines were needed. Later, colored toners became available, and several distinct line colors could be used, even simultaneously. For instance, in The Rescuers the characters' outlines are gray. White and blue toners were used for special effects, such as snow and water.

The APT process

Invented by Dave Spencer for the 1985 Disney film The Black Cauldron, the APT (Animation Photo Transfer) process was a technique for transferring the animators' art onto cels. Basically, the process was a modification of a repro-photographic process; the artists' work was photographed on high-contrast "litho" film, and the image on the resulting negative was then transferred to a cel covered with a layer of light-sensitive dye. The cel was exposed through the negative. Chemicals were then used to remove the unexposed portion. Small and delicate details were still inked by hand if needed. Spencer received an Academy Award for Technical Achievement for developing this process.

Cel overlay

A cel overlay is a cel with inanimate objects used to give the impression of a foreground when laid on top of a ready frame.[33] This creates the illusion of depth, but not as much as a multiplane camera would. A special version of cel overlay is called line overlay, made to complete the background instead of making the foreground, and was invented to deal with the sketchy appearance of xeroxed drawings. The background was first painted as shapes and figures in flat colors, containing rather few details. Next, a cel with detailed black lines was laid directly over it, each line is drawn to add more information to the underlying shape or figure and give the background the complexity it needed. In this way, the visual style of the background will match that of the xeroxed character cels. As the xerographic process evolved, line overlay was left behind.

Computers and traditional animation

The methods mentioned above describe the techniques of an animation process that originally depended on cels in its final stages, but painted cels are rare today as the computer moves into the animation studio, and the outline drawings are usually scanned into the computer and filled with digital paint instead of being transferred to cels and then colored by hand.[34] The drawings are composited in a computer program on many transparent "layers" much the same way as they are with cels,[35] and made into a sequence of images which may then be transferred onto film or converted to a digital video format.[36]

It is now also possible for animators to draw directly into a computer using a graphics tablet, Cintiq or a similar device, where the outline drawings are done in a similar manner as they would be on paper. The Goofy short How To Hook Up Your Home Theater (2007) represented Disney's first project based on the paperless technology available today. Some of the advantages are the possibility and potential of controlling the size of the drawings while working on them, drawing directly on a multiplane background and eliminating the need for photographing line tests and scanning.

Though traditional animation is now commonly done with computers, it is important to differentiate computer-assisted traditional animation from 3D computer animation, such as Toy Story and Ice Age. However, often traditional animation and 3D computer animation will be used together, as in Don Bluth's Titan A.E. and Disney's Tarzan and Treasure Planet. Most anime and many western animated series still use traditional animation today. DreamWorks executive Jeffrey Katzenberg coined the term "tradigital animation" to describe animated films produced by his studio which incorporated elements of traditional and computer animation equally, such as Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron and Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas.

Many video games such as Viewtiful Joe, The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker and others use "cel-shading" animation filters or lighting systems to make their full 3D animation appear as though it were drawn in a traditional cel-style. This technique was also used in the animated movie Appleseed, and cel-shaded 3D animation is typically integrated with cel animation in Disney films and in many television shows, such as the Fox animated series Futurama. In one scene of the 2007 Pixar movie Ratatouille, an illustration of Gusteau (in his cookbook), speaks to Remy (who, in that scene, was lost in the sewers of Paris) as a figment of Remy's imagination; this scene is also considered an example of cel-shading in an animated feature. More recently, animated shorts such as Paperman, Feast, and The Dam Keeper have used a more distinctive style of cel-shaded 3D animation, capturing a look and feel similar to a 'moving painting'.

Rotoscoping

Rotoscoping is a method of traditional animation invented by Max Fleischer in 1915, in which animation is "traced" over actual film footage of actors and scenery.[37] Traditionally, the live-action will be printed out frame by frame and registered. Another piece of paper is then placed over the live-action printouts and the action is traced frame by frame using a lightbox. The end result still looks hand-drawn but the motion will be remarkably lifelike. The films Waking Life and American Pop are full-length rotoscoped films. Rotoscoped animation also appears in the music videos for A-ha's song "Take On Me" and Kanye West's "Heartless". In most cases, rotoscoping is mainly used to aid the animation of realistically rendered human beings, as in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Peter Pan, and Sleeping Beauty.

A method related to conventional rotoscoping was later invented for the animation of solid inanimate objects, such as cars, boats, or doors. A small live-action model of the required object was built and painted white, while the edges of the model were painted with thin black lines. The object was then filmed as required for the animated scene by moving the model, the camera, or a combination of both, in real-time or using stop-motion animation. The film frames were then printed on paper, showing a model made up of the painted black lines. After the artists had added details to the object not present in the live-action photography of the model, it was xeroxed onto cels. A notable example is Cruella de Vil's car in Disney's One Hundred and One Dalmatians. The process of transferring 3D objects to cels was greatly improved in the 1980s when computer graphics advanced enough to allow the creation of 3D computer-generated objects that could be manipulated in any way the animators wanted, and then printed as outlines on paper before being copied onto cels using Xerography or the APT process. This technique was used in Disney films such as Oliver and Company (1988) and The Little Mermaid (1989). This process has more or less been superseded by the use of cel-shading.

Related to rotoscoping are the methods of vectorizing live-action footage, in order to achieve a very graphical look, like in Richard Linklater's film A Scanner Darkly.

Live-action hybrids

Similar to the computer animation and traditional animation hybrids described above, occasionally a production will combine both live-action and animated footage. The live-action parts of these productions are usually filmed first, the actors pretending that they are interacting with the animated characters, props, or scenery; animation will then be added into the footage later to make it appear as if it has always been there. Like rotoscoping, this method is rarely used, but when it is, it can be done to terrific effect, immersing the audience in a fantasy world where humans and cartoons co-exist. Early examples include the silent Out of the Inkwell (begun in 1919) cartoons by Max Fleischer and Walt Disney's Alice Comedies (begun in 1923). Live-action and animation were later combined in features such as Mary Poppins (1964), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), Space Jam (1996), and Enchanted (2007), among many others. The technique has also seen significant use in television commercials, especially for breakfast cereals marketed to children to interest them and boost sales.

Special effects animation

Besides traditionally animated characters, objects, and backgrounds, many other techniques are used to create special elements such as smoke, lightning and "magic", and to give the animation, in general, a distinct visual appearance. Today special effects are mostly done with computers, but earlier they had to be done by hand. To produce these effects, the animators used different techniques, such as drybrush, airbrush, charcoal, grease pencil, backlit animation, diffusing screens, filters, or gels. For instance, the Nutcracker Suite segment in Fantasia has a fairy sequence where stippled cels are used, creating a soft pastel look.

See also

References

Citations

- Laybourne 1998, pp. 202–203.

- Laybourne 1998, p. xv.

- Laybourne 1998, pp. 105–107.

- Laybourne 1998, p. 339.

- Laybourne 1998, pp. 302–313.

- "ANIMATO Animation Equipment". 14 May 2011. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2017.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Laybourne 1998, p. 233.

- Jones, Angie. (2007). Thinking animation : bridging the gap between 2D and CG. Boston, MA: Thomson Course Technology. ISBN 978-1-59863-260-6. OCLC 228168598.

- "1976 Charles Goodwin Sands Memorial Medal". graphics.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- Lewell, John (2017-07-03). "Behind the Screen at Hanna-Barbera" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-03. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- Robertson, Barbara (July 2002). "Part 7: Movie Retrospective". Computer Graphics World. 25 (7).

December 1991 Although 3D graphics debuted in earlier Disney animations, Beauty and the Beast is the first in which hand-drawn characters appear in a 3D background. Every frame of the film is scanned, created, or composited within Disney's computer animation production system (CAPS) co-developed with Pixar. (Premiere: (11/91)

- "Timeline". Computer Graphics World. 35 (6). Oct–Nov 2012.

DECEMBER 1991: Beauty and the Beast is the first Disney film with hand-drawn characters in a 3D background. Every frame is scanned, created, or composited within CAPS.

- "momotato.com - momotato Resources and Information". Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- Sazae-san is Last TV Anime Using Cels, Not Computers—Anime News Network

- Laybourne 1998, p. 241.

- Thomas & Johnston 1995, p. 30.

- Culhane 1989, p. 212.

- Laybourne 1998, p. 180.

- Segall, Mark (1996). "Plympton's Metamorphoses". Animation World Magazine.

- LaMarre 2009, p. 187.

- Maltin 1987, p. 277.

- Walt Disney's MultiPlane Camera (Filmed Feb. 13, 1957), retrieved 2019-09-17

- Multi-Plane Animation Basics | Stop Motion, retrieved 2019-09-17

- Maher, Michael (2015-09-30). "Visual Effects: How Matte Paintings are Composited into Film". RocketStock. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- "CONTENTdm". hrc.contentdm.oclc.org. Retrieved 2019-09-17.

- Malczyk, K. (2008-09-01). "Practicing Modernity: Female Creativity in the Weimar Republic. Edited by Christiane Schonfeld. Wurzburg: Konigshausen & Neumann, 2006. 353 pages. 48,00". Monatshefte. 100 (3): 439–440. doi:10.1353/mon.0.0033. ISSN 0026-9271. S2CID 142450235.

- Sobchack, Vivian Carol (2000). Meta Morphing: Visual Transformation and the Culture of Quick-change. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816633197.

- "Cinema: Mouse & Man". Time. 1937-12-27. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- Musker, John; Clements, Ron (2010). "Aladdin". 100 Animated Feature Films. doi:10.5040/9781838710514.0007. ISBN 9781838710514.

- ScreenPrism. "How did the multiplane camera invented for "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" redefine animation | ScreenPrism". screenprism.com. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- Laybourne 1998, p. 213.

- "A. Film L.A.: Nice Try, Bill..." Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- Laybourne 1998, p. 168.

- Laybourne 1998, pp. 30, 67.

- Laybourne 1998, p. 176.

- Laybourne 1998, pp. 354, 368.

- Laybourne 1998, p. 172.

Sources

- Blair, Preston (1994). Cartoon Animation. Laguana Hills, CA: Walter Foster Publishing. ISBN 156-010084-2.

- Culhane, Shamus (1989). Animation from Script to Screen. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 031-205052-6.

- LaMarre, Thomas (2009). The Anime Machine. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-5154-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laybourne, Kit (1998). The Animation Book : A Complete Guide to Animated Filmmaking—From Flip-Books to Sound Cartoons to 3-D Animation. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 051-788602-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maltin, Leonard (1987). Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-4522-5993-5.

- Thomas, Frank; Johnston, Ollie (1995). Disney Animation: The Illusion Of Life. Los Angeles: Disney Editions. ISBN 078-686070-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Richard (2002). The Animator's Survival Kit: A Manual of Methods, Principles, and Formulas for Classical, Computer, Games, Stop Motion, and Internet Animators. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 057-120228-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

Media related to Traditional animation at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Traditional animation at Wikimedia Commons