World Chess Championship 2013

The World Chess Championship 2013 was a match between reigning world champion Viswanathan Anand and challenger Magnus Carlsen, to determine the 2013 World Chess Champion. It was held from 9 to 22 November 2013 in Chennai, India, under the auspices of FIDE (the World Chess Federation).

| Defending champion | Challenger |

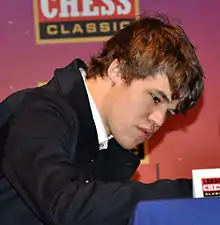

Viswanathan Anand |

Magnus Carlsen |

| 3½ | 6½ |

| Born 11 December 1969 43 years old |

Born 30 November 1990 22 years old |

| Winner of the 2012 World Chess Championship | Winner of the 2013 Candidates Tournament |

| Rating: 2775 (World No. 8)[1] | Rating: 2870 (World No. 1)[1] |

| ← 2012 | 2014 → |

Carlsen won the match 6½–3½ after ten of the twelve scheduled games, becoming the new world chess champion. This was heralded by Garry Kasparov and others as the start of a new era in chess, with Carlsen being the first champion to have developed his game in the age of super-strong chess computers.[2][3]

Candidates Tournament

The challenger was determined in the 2013 Candidates Tournament, which was a double round-robin tournament. (This was the first time in 51 years that the round-robin format had been used for a Candidates,[4] though it had been used for the 2005 (FIDE) and 2007 World championships). It took place in the Institution of Engineering and Technology, Savoy Place, London, from 15 March to 1 April 2013.[5] The participants were:[6]

| Qualification path | Player |

|---|---|

| The top three finishers in the Chess World Cup 2011 | |

| The three highest rated players in the world, excluding any of the above or below (average from July 2011 and January 2012 FIDE rating lists) |

|

| Candidates Tournament Organizing committee's wild card (FIDE rating in January 2012 at least 2700)[6][7] |

|

| Loser of the World Chess Championship 2012 |

The tournament had a prize fund of €510,000 ($691,101). Prize money was shared between players tied on points; tiebreaks were not used to allocate it. The prizes for each place were as follows:[6]

- 1st place – €115,000

- 2nd place – €107,000

- 3rd place – €91,000

- 4th place – €67,000

- 5th place – €48,000

- 6th place – €34,000

- 7th place – €27,000

- 8th place – €21,000

Results

Before the tournament Carlsen was considered the favourite, with Kramnik and Aronian being deemed his biggest rivals. Ivanchuk was considered an uncertain variable, due to his instability, and the other players were considered less likely to win the event.[8][9]

During the first half of the tournament, Aronian and Carlsen were considered the main contestants for first place. At the halfway point they were tied for first, one-and-a-half points ahead of Kramnik and Svidler. In the second half Kramnik, who had drawn his first seven games, became a serious contender after scoring four wins, while Aronian lost three games, and was thus left behind in the race. Carlsen started the second half by staying ahead of the field, but a loss to Ivanchuk allowed Kramnik to take the lead in round 12 by defeating Aronian.[10] In the penultimate round Carlsen pulled level with Kramnik by defeating Radjabov, while Kramnik drew against Gelfand.[11]

Before the last round only Carlsen and Kramnik could win the tournament; they were equal on 8½ points, 1½ points ahead of Svidler and Aronian. Carlsen had the better tie break (on the first tie break the score from their individual games was 1–1, but Carlsen was ahead on the second tie break due to having more wins), and this would not change if they both scored the same in the final round. Therefore, Kramnik, who had black against Ivanchuk, needed to outperform Carlsen, who had white against Svidler. Carlsen played to win, since that would guarantee him the tournament victory regardless of Kramnik's result; similarly, Kramnik knew that the odds of Carlsen losing with white were minute, and he went all-in against Ivanchuk with the Pirc defense. This backfired and Ivanchuk obtained an early advantage, while Carlsen got a level position against Svidler. Carlsen later got into serious time trouble and did not defend adequately against Svidler's attack, which gave Svidler a winning endgame. Meanwhile, Ivanchuk had outplayed Kramnik, who resigned a few minutes after Carlsen lost. Thus the tournament was won by Carlsen on the second tiebreak.[12] Carlsen's win earned him the right to challenge the reigning world champion, Vishy Anand for the world title.

Final standings of the 2013 Candidates Tournament[13] Rank Player Rating

March 2013[14]1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Points Tiebreaks[6] H2H Wins 1  Magnus Carlsen (NOR)

Magnus Carlsen (NOR)2872 ½ ½ 0 1 ½ ½ 1 1 1 ½ 0 ½ ½ 1 8½ 1 5 2  Vladimir Kramnik (RUS)

Vladimir Kramnik (RUS)2810 ½ ½ 1 ½ ½ 1 ½ ½ ½ 1 ½ 0 1 ½ 8½ 1 4 3  Peter Svidler (RUS)

Peter Svidler (RUS)2747 0 1 ½ 0 1 ½ ½ ½ ½ ½ 1 ½ 1 ½ 8 1½ 4 4  Levon Aronian (ARM)

Levon Aronian (ARM)2809 ½ ½ 0 ½ ½ 0 1 0 ½ ½ 1 1 1 1 8 ½ 5 5  Boris Gelfand (ISR)

Boris Gelfand (ISR)2740 0 0 ½ ½ ½ ½ 1 0 ½ ½ ½ ½ ½ 1 6½ 1 2 6  Alexander Grischuk (RUS)

Alexander Grischuk (RUS)2764 ½ 0 0 ½ ½ ½ ½ ½ ½ ½ 1 ½ ½ ½ 6½ 1 1 7  Vassily Ivanchuk (UKR)

Vassily Ivanchuk (UKR)2757 ½ 1 1 ½ ½ 0 0 0 ½ ½ ½ 0 1 0 6 — 3 8  Teimour Radjabov (AZE)

Teimour Radjabov (AZE)2793 0 ½ ½ 0 ½ 0 0 0 0 ½ ½ ½ 1 0 4 — 1

Numbers in parentheses indicate players' scores prior to the round.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Championship match

The Championship match between Viswanathan Anand and Magnus Carlsen was held from 9 to 22 November 2013 in Chennai, India, under the auspices of FIDE.

Previous head-to-head record

Prior to the match, from 2005 to 18 June 2013, Anand and Carlsen played 29 games against each other at classical time controls, out of which Anand won six, Carlsen won three, and twenty were drawn.[15]

| Head-to-head record[16] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anand wins | Draw | Carlsen wins | Total | ||

| Classical | Anand (white) – Carlsen (black) | 2 | 11 | 0 | 13 |

| Carlsen (white) – Anand (black) | 4 | 9 | 3 | 16 | |

| Total | 6 | 20 | 3 | 29 | |

| Blitz / rapid / exhibition | 9 | 16 | 8 | 33 | |

| Total | 15 | 36 | 11 | 62 | |

Prize fund

The prize fund was 2,650,000 Euros, of which 60 percent would go to the winner and 40 percent to the loser if the match ended within the 12 regular games. If the match went to tie-breaks, the winner would have received 55 percent and the loser 45 percent.

Seconds

Both Anand and Carlsen had a team of seconds to aid in their match preparation.[17] Anand's seconds for the match were Surya Ganguly and Radosław Wojtaszek, who had helped him in four previous World Championship matches; his primary second Peter Heine Nielsen had been hired away earlier in the year by Carlsen, under agreement that he would not help Carlsen during this match against Anand.[18] During the opening press conference, Anand revealed his new seconds to be Krishnan Sasikiran, Sandipan Chanda and Peter Leko.[17][19]

Carlsen at first declined to reveal his seconds,[20] but after the match revealed that Jon Ludvig Hammer had been doing opening preparation from Norway.[21] Ian Nepomniachtchi and Laurent Fressinet have been supposed as seconds.[22] Over a year after the match Carlsen also revealed that Pavel Eljanov had been among his seconds in the Chennai match.[23]

Schedule and results

The match between Anand and Carlsen took place at the Hyatt Regency Chennai hotel in Chennai, India,[24] from 9 to 22 November 2013, under the auspices of FIDE.[25][26] Twelve classical games were scheduled, each starting at 3 pm local time (09:30 UTC). Rest days were to take place after games 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 11. Had the match been tied after the 12th game on 26 November tie-break games would have been played on 28 November.[27] As the match was decided before the 12th game, the remaining scheduled games were cancelled.[27]

The time control for the games gave each player 120 minutes for the first 40 moves, 60 minutes for moves 41–60 and 15 minutes for the rest of the game, with an increment of 30 seconds per move starting after move 61.[27] Tie-break games were meant to have increasingly limited time controls.[27] Carlsen won $1.53 million while Anand received $1.02 million for this match.[28]

World Chess Championship 2013 Rating Game 1

9 Nov.Game 2

10 Nov.Game 3

12 Nov.Game 4

13 Nov.Game 5

15 Nov.Game 6

16 Nov.Game 7

18 Nov.Game 8

19 Nov.Game 9

21 Nov.Game 10

22 Nov.Game 11

24 Nov.Game 12

26 Nov.Points  Viswanathan Anand (India)

Viswanathan Anand (India)2775 ½ ½ ½ ½ 0 0 ½ ½ 0 ½ Not required 3½  Magnus Carlsen (Norway)

Magnus Carlsen (Norway)2870 ½ ½ ½ ½ 1 1 ½ ½ 1 ½ 6½

Games

The player named first plays the white pieces.

Game 1, Carlsen–Anand, ½–½

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Carlsen chose a quiet line, but his play was slightly inaccurate, and he accepted a draw after 16 moves in lieu of a threefold repetition.[29]

- Reti Opening, King's Indian Attack (ECO A07)

1. Nf3 d5 2. g3 g6 3. Bg2 Bg7 4. d4 c6 5. 0-0 Nf6 6. b3 0-0 7. Bb2 Bf5 8. c4 Nbd7 9. Nc3 dxc4 10. bxc4 Nb6 11. c5 Nc4 12. Bc1 Nd5 13. Qb3 (diagram) Na5 14. Qa3 Nc4 15. Qb3 Na5 16. Qa3 Nc4 ½–½

Game 2, Anand–Carlsen, ½–½

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Anand opened with 1.e4, and Carlsen responded with the Caro–Kann Defence, his first time doing so in a competitive game since 2011. Anand castled queenside on move 14, which was followed by a knight exchange in the centre, after which Carlsen advanced his queen to d5 (see diagram). This enabled a trade of queens, and, to the surprise of commentators and the audience, Anand accepted it, rather than pressing forward with 18.Qg4. The resulting endgame was balanced; Anand exerted pressure on Carlsen's kingside pawn shield with his rooks, eliciting a repetition of moves and a draw.[30]

- Caro–Kann Defence, Classical Variation (ECO B18)[31]

1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 dxe4 4. Nxe4 Bf5 5. Ng3 Bg6 6. h4 h6 7. Nf3 e6 8. Ne5 Bh7 9. Bd3 Bxd3 10. Qxd3 Nd7 11. f4 Bb4+ 12. c3 Be7 13. Bd2 Ngf6 14. 0-0-0 0-0 15. Ne4 Nxe4 16. Qxe4 Nxe5 17. fxe5 Qd5 (diagram) 18. Qxd5 cxd5 19. h5 b5 20. Rh3 a5 21. Rf1 Rac8 22. Rg3 Kh7 23. Rgf3 Kg8 24. Rg3 Kh7 25. Rgf3 Kg8 ½–½

Game 3, Carlsen–Anand, ½–½

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Carlsen opened with his king knight as in game 1, but played 3.c4, and Anand took the pawn on the next move. Anand gained some advantage in the middlegame when Carlsen had to retreat his queen to h1 and became short on time. However, with the temporary pawn sacrifice 28.e3 (which chess Grandmaster and commentator Sergei Shipov described as "the best known, boldest and most debatable" move of 2013),[32] Carlsen opened the position and managed to reactivate his pieces. From then on Anand did not play the most aggressive moves (e.g. he chose 29...Bd4 instead of Bxb2; later 34...Rf8 was possible) but began to exchange pieces, and offered a draw after move 41, which Carlsen declined. After the exchange of queens, an opposite-colored bishops endgame was reached, and the players soon agreed to a draw.

- Réti Opening, King's Indian Attack (ECO A07)

1. Nf3 d5 2. g3 g6 3. c4 dxc4 4. Qa4+ Nc6 5. Bg2 Bg7 6. Nc3 e5 7. Qxc4 Nge7 8. 0-0 0-0 9. d3 h6 10. Bd2 Nd4 11. Nxd4 exd4 12. Ne4 c6 13. Bb4 Be6 14. Qc1 Bd5 15. a4 b6 16. Bxe7 Qxe7 17. a5 Rab8 18. Re1 Rfc8 19. axb6 axb6 20. Qf4 Rd8 21. h4 Kh7 22. Nd2 Be5 23. Qg4 h5 24. Qh3 Be6 25. Qh1 c5 26. Ne4 Kg7 27. Ng5 b5 28. e3 dxe3 29. Rxe3 (diagram) Bd4 30. Re2 c4 31. Nxe6+ fxe6 32. Be4 cxd3 33. Rd2 Qb4 34. Rad1 Bxb2 35. Qf3 Bf6 36. Rxd3 Rxd3 37. Rxd3 Rd8 38. Rxd8 Bxd8 39. Bd3 Qd4 40. Bxb5 Qf6 41. Qb7+ Be7 42. Kg2 g5 43. hxg5 Qxg5 44. Bc4 h4 45. Qc7 hxg3 46. Qxg3 e5 47. Kf3 Qxg3+ 48. fxg3 Bc5 49. Ke4 Bd4 50. Kf5 Bf2 51. Kxe5 Bxg3+ ½–½

Game 4, Anand–Carlsen, ½–½

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Carlsen chose the solid Berlin Defence to the Ruy Lopez. He grabbed a pawn at move 18, and a complex position developed. Black remained a pawn up, but "Anand found a fantastic resource in 35.Ne4! which helped him to finally open up the black king and equalise the play."[33]

- Ruy Lopez, Berlin Defence, Open Variation (ECO C67)

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6 4. 0-0 Nxe4 5. d4 Nd6 6. Bxc6 dxc6 7. dxe5 Nf5 8. Qxd8+ Kxd8 9. h3 Bd7 10. Rd1 Be7 11. Nc3 Kc8 12. Bg5 h6 13. Bxe7 Nxe7 14. Rd2 c5 15. Rad1 Be6 16. Ne1 Ng6 17. Nd3 b6 18. Ne2 Bxa2 19. b3 c4 20. Ndc1 cxb3 21. cxb3 Bb1 22. f4 Kb7 23. Nc3 Bf5 24. g4 Bc8 25. Nd3 h5 26. f5 Ne7 27. Nb5 hxg4 28. hxg4 Rh4 29. Nf2 Nc6 30. Rc2 a5 31. Rc4 g6 32. Rdc1 Bd7 33. e6 fxe6 34. fxe6 Be8 (diagram) 35. Ne4 Rxg4+ 36. Kf2 Rf4+ 37. Ke3 Rf8 38. Nd4 Nxd4 39. Rxc7+ Ka6 40. Kxd4 Rd8+ 41. Kc3 Rf3+ 42. Kb2 Re3 43. Rc8 Rdd3 44. Ra8+ Kb7 45. Rxe8 Rxe4 46. e7 Rg3 47. Rc3 Re2+ 48. Rc2 Ree3 49. Ka2 g5 50. Rd2 Re5 51. Rd7+ Kc6 52. Red8 Rge3 53. Rd6+ Kb7 54. R8d7+ Ka6 55. Rd5 Re2+ 56. Ka3 Re6 57. Rd8 g4 58. Rg5 Rxe7 59. Ra8+ Kb7 60. Rag8 a4 61. Rxg4 axb3 62. R8g7 Ka6 63. Rxe7 Rxe7 64. Kxb3 ½–½

Game 5, Carlsen–Anand, 1–0

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Anand's 45...Rc1+ was called the decisive mistake,[34] after which White was able to defend the a3-pawn, exchange bishops, and win a second pawn. Instead, 45...Ra1, attacking White's a3-pawn, would have kept the balance.[35] With this win, Carlsen took a 3–2 lead.

- Queen's Gambit Declined, Semi-Slav, Marshall Gambit (ECO D31)

1. c4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 c6 4. e4 dxe4 5. Nxe4 Bb4+ 6. Nc3 c5 7. a3 Ba5 8. Nf3 Nf6 9. Be3 Nc6 10. Qd3 cxd4 11. Nxd4 Ng4 12. 0-0-0 Nxe3 13. fxe3 Bc7 14. Nxc6 bxc6 15. Qxd8+ Bxd8 16. Be2 Ke7 17. Bf3 Bd7 18. Ne4 Bb6 19. c5 f5 20. cxb6 fxe4 21. b7 Rab8 22. Bxe4 Rxb7 23. Rhf1 Rb5 24. Rf4 g5 25. Rf3 h5 26. Rdf1 Be8 27. Bc2 Rc5 28. Rf6 h4 29. e4 a5 30. Kd2 Rb5 31. b3 Bh5 32. Kc3 Rc5+ 33. Kb2 Rd8 34. R1f2 Rd4 35. Rh6 Bd1 36. Bb1 Rb5 37. Kc3 c5 38. Rb2 e5 39. Rg6 a4 40. Rxg5 Rxb3+ 41. Rxb3 Bxb3 42. Rxe5+ Kd6 43. Rh5 Rd1 44. e5+ Kd5 45. Bh7 (diagram) Rc1+ 46. Kb2 Rg1 47. Bg8+ Kc6 48. Rh6+ Kd7 49. Bxb3 axb3 50. Kxb3 Rxg2 51. Rxh4 Ke6 52. a4 Kxe5 53. a5 Kd6 54. Rh7 Kd5 55. a6 c4+ 56. Kc3 Ra2 57. a7 Kc5 58. h4 1–0

Game 6, Anand–Carlsen, 0–1

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

After a solid opening, a series of exchanges brought about a heavy-piece endgame that was reckoned to be drawn. With 38.Qg3, Anand sacrificed a pawn in order to reach a drawn rook endgame, and a second pawn was sacrificed with 44.h5 in order to disconnect Black's kingside pawns. Carlsen continued playing and sacrificed both of his extra pawns in order to advance his f-pawn. The decisive error was 60.Ra4; instead, 60.b4 was suggested by analysts and chess engines as the only move that leads to a draw with best play, since the advancing b-pawn gives White queening threats that yield counterplay and make an exchange of rooks acceptable.[36] After 60.Ra4, Carlsen's pawn sacrifice 60...h3 turned his f-pawn into a decisive passed pawn, and Anand resigned a few moves later.[37]

- Ruy Lopez, Berlin Defence (ECO C65)

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6 4. d3 Bc5 5. c3 0-0 6. 0-0 Re8 7. Re1 a6 8. Ba4 b5 9. Bb3 d6 10. Bg5 Be6 11. Nbd2 h6 12. Bh4 Bxb3 13. axb3 Nb8 14. h3 Nbd7 15. Nh2 Qe7 16. Ndf1 Bb6 17. Ne3 Qe6 18. b4 a5 19. bxa5 Bxa5 20. Nhg4 Bb6 21. Bxf6 Nxf6 22. Nxf6+ Qxf6 23. Qg4 Bxe3 24. fxe3 Qe7 25. Rf1 c5 26. Kh2 c4 27. d4 Rxa1 28. Rxa1 Qb7 29. Rd1 Qc6 30. Qf5 exd4 31. Rxd4 Re5 32. Qf3 Qc7 33. Kh1 Qe7 34. Qg4 Kh7 35. Qf4 g6 36. Kh2 Kg7 37. Qf3 Re6 38. Qg3 Rxe4 39. Qxd6 Rxe3 40. Qxe7 Rxe7 41. Rd5 Rb7 42. Rd6 f6 43. h4 Kf7 44. h5 gxh5 45. Rd5 Kg6 46. Kg3 Rb6 47. Rc5 f5 48. Kh4 Re6 49. Rxb5 Re4+ 50. Kh3 Kg5 51. Rb8 h4 52. Rg8+ Kh5 53. Rf8 Rf4 54. Rc8 Rg4 55. Rf8 Rg3+ 56. Kh2 Kg5 57. Rg8+ Kf4 58. Rc8 Ke3 59. Rxc4 f4 (diagram) 60. Ra4 h3 61. gxh3 Rg6 62. c4 f3 63. Ra3+ Ke2 64. b4 f2 65. Ra2+ Kf3 66. Ra3+ Kf4 67. Ra8 Rg1 0–1

Game 7, Anand–Carlsen, ½–½

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

In the opening, Anand exchanged his bishop for a knight, which led to a structure similar to that of the Exchange Variation of the Ruy Lopez where Black has doubled pawns. Carlsen defended accurately, and after further exchanges the two players settled for a repetition of moves around move 30.[38]

- Ruy Lopez, Berlin Defence (ECO C65)

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6 4. d3 Bc5 5.Bxc6 dxc6 6. Nbd2 Bg4 7. h3 Bh5 8. Nf1 Nd7 9. Ng3 Bxf3 10. Qxf3 g6 11. Be3 Qe7 12. 0-0-0 0-0-0 13. Ne2 Rhe8 14. Kb1 b6 15. h4 Kb7 16. h5 Bxe3 17. Qxe3 Nc5 18. hxg6 hxg6 19. g3 a5 20. Rh7 Rh8 21. Rdh1 Rxh7 22. Rxh7 Qf6 23. f4 Rh8 24. Rxh8 Qxh8 25. fxe5 Qxe5 26. Qf3 f5 27. exf5 gxf5 28. c3 Ne6 29. Kc2 (diagram) Ng5 30. Qf2 Ne6 31. Qf3 Ng5 32. Qf2 Ne6 ½–½

Game 8, Carlsen–Anand, ½–½

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Carlsen opted for 1.e4 for the first time in the match and the game developed into a Ruy Lopez, Berlin Defence in which he managed to trade pieces and reach a symmetrical position with a draw in 33 moves. Many were disappointed that Anand chose the Berlin Defence instead of trying a more combative opening, given that he was down two points. After the game, Anand said he "had not prioritised 1.e4" in his preparation. He also said that the match situation was "fairly clear" and that he would "liven it up" in the next game.[39]

- Ruy Lopez, Berlin Defence (ECO C65)

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6 4. 0-0 Nxe4 5. Re1 Nd6 6. Nxe5 Be7 7. Bf1 Nxe5 8. Rxe5 0-0 9. d4 Bf6 10. Re1 Re8 11. c3 Rxe1 12. Qxe1 Ne8 13. Bf4 d5 14. Bd3 g6 15. Nd2 Ng7 16. Qe2 c6 17. Re1 Bf5 18. Bxf5 Nxf5 19. Nf3 Ng7 20. Be5 Ne6 21. Bxf6 Qxf6 22. Ne5 Re8 23. Ng4 Qd8 24. Qe5 Ng7 25. Qxe8+ Nxe8 26. Rxe8+ Qxe8 27. Nf6+ Kf8 28. Nxe8 Kxe8 29. f4 f5 30. Kf2 b5 31. b4 Kf7 32. h3 h6 33. h4 h5 (diagram) ½–½

Game 9, Anand–Carlsen, 0–1

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Anand played a sharp line against the Nimzo-Indian Defence that gave him attacking chances. Instead of 20.axb4, which according to Hikaru Nakamura "was not in the spirit of the position at all", either 20.a4 or 20.f5 were suggested as more promising continuations for White.[40] Afterwards, Carlsen defended accurately, creating counterplay on the queenside, and ultimately queening his b-pawn with check while Anand was shifting his heavy pieces over to his mating attack. Anand should have answered 27...b1=Q+ with 28.Bf1. ChessBase gives the best line as 28.Bf1 Qd1 29.Rh4 Qh5 (Black must sacrifice his new queen in order to stave off checkmate) 30.Nxh5 gxh5 31.Rxh5 Bf5 32.Bh3 Bg6 33.e6 Nxf6 34.gxf6 Qxf6 35.Rf5 Qxe6 36.Re5 Qd6, which is probably a draw. Instead, Anand blundered with 28.Nf1 and resigned after 28...Qe1, since after 29.Rh4 Qxh4 30.Qxh4, Black emerges a rook up.[41]

- Nimzo-Indian Defence, Sämisch Variation (ECO E25)

1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Bb4 4. f3 d5 5. a3 Bxc3+ 6. bxc3 c5 7. cxd5 exd5 8. e3 c4 9. Ne2 Nc6 10. g4 0-0 11. Bg2 Na5 12. 0-0 Nb3 13. Ra2 b5 14. Ng3 a5 15. g5 Ne8 16. e4 Nxc1 17. Qxc1 Ra6 18. e5 Nc7 19. f4 b4 20. axb4 axb4 21. Rxa6 Nxa6 22. f5 b3 23. Qf4 Nc7 24. f6 g6 25. Qh4 Ne8 26. Qh6 b2 27. Rf4 b1=Q+ (diagram) 28. Nf1 Qe1 0–1

Game 10, Carlsen–Anand, ½–½

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Anand played the Sicilian Defence, but with 3.Bb5+ Carlsen avoided the sharpest main lines. Anand's 28...Qg5 was a mistake, allowing Carlsen to play 29.e5 with strong pressure on Black's d6-pawn. Maintaining the tension with 30.Nc3, 30.Ng3, or 30.b4 should have given White a winning game, but Carlsen erred with 30.exd6, releasing the tension and allowing Anand to recoup the pawn soon after. The players traded down to a knight endgame where White had some advantage, and Carlsen may have missed a win by playing 43.Nd6 instead of 43.Nd2.[42] The game ended in a draw due to insufficient mating material.

- Sicilian Defence, Canal–Sokolsky Attack (ECO B51)

1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. Bb5+ Nd7 4. d4 cxd4 5. Qxd4 a6 6. Bxd7+ Bxd7 7. c4 Nf6 8. Bg5 e6 9. Nc3 Be7 10. 0-0 Bc6 11. Qd3 0-0 12. Nd4 Rc8 13. b3 Qc7 14. Nxc6 Qxc6 15. Rac1 h6 16. Be3 Nd7 17. Bd4 Rfd8 18. h3 Qc7 19. Rfd1 Qa5 20. Qd2 Kf8 21. Qb2 Kg8 22. a4 Qh5 23. Ne2 Bf6 24. Rc3 Bxd4 25. Rxd4 Qe5 26. Qd2 Nf6 27. Re3 Rd7 28. a5 Qg5 29. e5 Ne8 (diagram) 30. exd6 Rc6 31. f4 Qd8 32. Red3 Rcxd6 33. Rxd6 Rxd6 34. Rxd6 Qxd6 35. Qxd6 Nxd6 36. Kf2 Kf8 37. Ke3 Ke7 38. Kd4 Kd7 39. Kc5 Kc7 40. Nc3 Nf5 41. Ne4 Ne3 42. g3 f5 43. Nd6 g5 44. Ne8+ Kd7 45. Nf6+ Ke7 46. Ng8+ Kf8 47. Nxh6 gxf4 48. gxf4 Kg7 49. Nxf5+ exf5 50. Kb6 Ng2 51. Kxb7 Nxf4 52. Kxa6 Ne6 53. Kb6 f4 54. a6 f3 55. a7 f2 56. a8=Q f1=Q 57. Qd5 Qe1 58. Qd6 Qe3+ 59. Ka6 Nc5+ 60. Kb5 Nxb3 61. Qc7+ Kh6 62. Qb6+ Qxb6+ 63. Kxb6 Kh5 64. h4 Kxh4 65. c5 Nxc5 ½–½

With this draw, Carlsen won the World Championship match 6½–3½, becoming the new world chess champion.[43]

Timeline of changes

There were several changes and controversies in the process for choosing the challenger and hosts for the championship. A timeline is found below.

2011

- 9 August. The All India Chess Federation was given a "first option" of three months following the 2012 World Chess Championship, to make a proposal for the organisation of the 2013 World Chess Championship.[44]

- 19 September. FIDE published the rules, regulations and qualification criteria for the Candidates Tournament of the FIDE World Championship Cycle 2011–13.[6][45]

2012

- 21 February. FIDE announced negotiations with the Chess Network Company (CNC) and AGON for the World Championship Cycle. Media, web and software rights of the events of the World Championship Cycle were awarded to CNC. AGON was tasked with organising the events and securing the necessary sponsorship funds.[46]

- 3 March. AGON awarded the Candidates Tournament dated 24 October – 12 November 2012 to London.[47]

- 28 March. FIDE and AGON announced 13–31 March 2013 as new dates for the Candidates matches in London.[48]

- 30 May. Anand won the 2012 World Chess Championship, thus qualifying for the 2013 World Chess Championship.[49] His challenger during the 2012 World Chess Championship Boris Gelfand qualified for the 2013 Candidates Tournament.[6]

- 30 August. Latest deadline for the All India Chess Federation to redeem the three-month option to make a proposal for the organisation of the 2013 World Chess Championship.[44]

- 25 October. The Indian Express reported that the All India Chess Federation did not act during the three-month window provided by FIDE to exercise the "first option" to host the final. FIDE Vice President Israel Gelfer commented that "the venue of the match will be decided when AGON, which has the rights and the obligation to organise the cycle, chooses and announces it."[50]

2013

- 1 April. Carlsen won the Candidates Tournament in London and thus qualified for the World Chess Championship.

- 8 April. Jayalalithaa Jayaram, the Chief Minister of the state of Tamil Nadu, India, announced that Chennai will host the 2013 World Chess Championship, and said that the event will have a budget of 290 million Indian rupees (around €4,000,000).[51]

- 19 April. FIDE, the All India Chess Federation and the Tamil Nadu State Chess Association signed a Memorandum of Understanding. FIDE Vice President Israel Gelfer said that the venue of the 2013 World Chess Championship would be set within 21 days.[52]

- 3 May. Jøran Aulin-Jansson, the president of the Norwegian Chess Federation, sent an open letter of protest to FIDE, writing "We strongly urge FIDE to facilitate a procedure that enables other interested parties to bid for the [2013 World Chess Championship]." Just a few hours later Bertrand Delanoë, the mayor of Paris, announced that the capital of France "is ready to host the [2013] World Chess Championship", offering a budget of €3,446,280 and a prize fund of €2,650,000 (Chennai offered €2,576,280 and €1,940,000, respectively).[53]

- 5 May. FIDE confirmed Chennai as the venue for the 2013 World Chess Championship.[54]

- 6 May. Carlsen made a statement saying, "I'm deeply disappointed and surprised by the FIDE decision to sign a contract for the 2013 match without going through the bidding process outlined in the WC regulations, and for not choosing neutral ground. The bid from Paris clearly showed that it would be possible to have more options to choose from. The lack of transparency, predictability and fairness is unfortunate for chess as a sport and for chess players."[55]

- 7 May. FIDE published a press release according to which on 24 January it and AGON "agreed not to open a bidding procedure, but to grant an option to India, as requested", and claiming that "FIDE tried its hardest to convince India to split the match [between India and Norway], but they refused."[56]

- 28 May. The Hyatt Regency Chennai hotel was announced as the venue for the 2013 World Chess Championship.[24]

References

- "Top 100 Players November 2013". Ratings.fide.com. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- Garry Kasparov (25 November 2013). "A New King for a New Era in Chess". Time. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- Weisenthal, Joe (22 November 2013). "22-YEAR-OLD MAGNUS CARLSEN WINS WORLD CHESS CHAMPIONSHIP — And Chess Enters A Whole New Era". Business Insider. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- Doggers, Peter (11 March 2013). "FIDE Candidates: a historical perspective". ChessVibes. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- Doggers, Peter (15 March 2013). "FIDE Candidates' Tournament officially opened by Ilyumzhinov". ChessVibes. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- "Rules & regulations for the Candidates Tournament of the FIDE World Championship cycle 2011–2013" (PDF). FIDE. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- Doggers, Peter (10 February 2012). "The Candidates' in London; is FIDE selling its World Championship cycle?". ChessVibes. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- Doggers, Peter (13 March 2013). "FIDE Candidates: Predictions". ChessVibes. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Unudurti, Jaideep (8 March 2013). "Even as a student, you have to watch the games live: Viswanathan Anand". The Economic Times. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Doggers, Peter (30 March 2013). "Candidates R12 – full report, pictures, videos". ChessBase News. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Doggers, Peter (1 April 2013). "Candidates R13 – pictures and postmortems". ChessBase News. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Ramírez, Alejandro (1 April 2013). "Candidates R14 – leaders lose, Carlsen qualifies". ChessBase News. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- "Tournament standings". FIDE. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- "FIDE Top players – Top 100 Players March 2013". FIDE. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- Karmarkar, Amit (3 April 2013). "Anand vs Carlsen fills void for Fischer vs Kasparov". The Times of India. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- "Anand vs. Carlsen". Chessgames.com. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- "World Chess Championship: Role of the 'seconds'". The Hindu. 4 November 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- "Carlsen catches coach of World Champion". ChessBase News. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- "Anand – Carlsen 2013, seconds preview (#9)". Chessdom. 30 October 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- "WCh Chennai: Press conference and news reports". ChessBase News. 7 November 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- Støstad, Mads Nyborg; Røren, Nils Fredrik (24 November 2013). "Carlsen hadde kun kontakt med én – Sport" (in Norwegian). NRK. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- Magotra, Ashish (26 November 2013). "Magnus Carlsen's mysterious seconds revealed!". Firstpost. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Carlsen Is Grateful to His Seconds and Helpers, Kasparov Included. Full List Revealed".

- "Five-star venue for Anand-Carlsen tie". The Times of India. 28 May 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- "FIDE calendar". FIDE. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Doggers, Peter (5 November 2013). "In Chennai (part 2, with first pics of the venue!)". ChessVibes. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "Rules & regulations for the FIDE World Championship Match (FWCM) 2013" (PDF). FIDE. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- Doggers, Peter (22 November 2013). "Magnus Carlsen World Champion of Chess". ChessVibes. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- "Chennai WC G1: Anand holds Carlsen to 16-move draw". Chessbase News. 9 November 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- "Another quick draw by Anand and Carlsen". FIDE. 10 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- "More moves but quicker draw". Chess Base. 10 November 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- "KC-Review of 2013 with Sergey Shipov". Crestbook. 17 January 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- "Berlin Wall troubles Anand, fourth game drawn". FIDE. 13 November 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- Ramírez, Alejandro (15 November 2013). "Chennai 05: First blood, what next?". ChessBase News. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- "Carlsen Beats Anand in World Championship Game 5". ChessVibes. 15 November 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- Lahlum, Hans Olav; et al. (16 November 2013). "Se Carlsen-fellen som lurte Anand trill rundt" (in Norwegian). VG TV. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- "Chennai G6: Carlsen wins second straight". ChessBase News. 16 November 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- "World Chess: Game 7 between Anand and Carlsen ends in a draw". Times of India. 18 November 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- "Carlsen forces quick draw in World Championship Game 8". The Week in Chess. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- Crowther, Mike (21 November 2013). "Carlsen on the brink of becoming World Chess Champion after game 9 win". Chessvibes. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- "Chennai G9: Magnus .44 beats battling Anand". ChessBase News. 21 November 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "Chennai Final: Magnus Victorious". ChessBase News. 22 November 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- "Chennai G10: Magnus Carlsen is the new World Champion!". ChessBase News. 22 November 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- "World Championships Matches – Press Release". FIDE. 9 August 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- "Candidates Tournament 2012". Chessdom. 19 September 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- "Agreement of FIDE with CNC and AGON". FIDE. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- "Chess Candidates Tournament to Take Place in London". FIDE. 5 March 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- "FIDE Announces Dates for World Chess Championship Cycles". FIDE. 28 March 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- "World Champion Viswanathan Anand retains the title". FIDE. 30 May 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- Natraj, Raakesh (25 October 2012). "India sits on offer, may miss hosting Anand in world chess final". The Indian Express. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- "Breaking: World Championship 2013 in Chennai?". ChessBase News. 8 April 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- "MOU signed for World Championship in Chennai". ChessBase News. 19 April 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- "Norway sends complaint, Paris ready to bid". ChessBase News. 3 May 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- Doggers, Peter (5 May 2013). "FIDE confirms Chennai as venue for Anand-Carlsen match". ChessVibes. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- Doggers, Peter (6 May 2013). "Carlsen 'deeply disappointed and surprised', will 'start preparing'". ChessVibes. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- Doggers, Peter (7 May 2013). "FIDE: 'Norway could organize half the match, but India refused'". ChessVibes. Retrieved 11 May 2013.