Xyston

The xyston (Ancient Greek: ξυστόν "spear, javelin; pointed or spiked stick, goad (lit. 'shaved')"), a derivative of the verb ξύω "scrape, shave", was a type of a long thrusting spear in ancient Greece. It measured about 3.5–4.25 meters (11.5–13.9 ft) long and was probably held by the cavalryman with both hands, although the depiction of Alexander the Great's xyston on the Alexander Mosaic in Pompeii (see figure), suggests that it could also be used single handed. It had a wooden shaft and a spear-point at both ends. Possible reasons for the secondary spear-tip were that it acted partly as a counterweight and also served as a backup in case the xyston was broken in action. The xyston is usually mentioned in context with the hetairoi (ἑταῖροι), the cavalry forces of ancient Macedon. After Alexander the Great's death, the hetairoi were named xystophoroi (ξυστοφόροι, "spear-bearers") because of their use of the xyston lance. In his Greek-written Bellum Judaicum, the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus uses the term xyston to describe the Roman throwing javelin, the pilum.

The xyston was wielded either underarm or overarm, presumably as a matter of personal preference. It was also known, especially later, as the kontos; meaning literally "barge-pole"; the name possibly originated as a slang term for the weapon.

Basic composition

The Xyston is a type of spear.[1] It is composed of a long wood staff and two pointed ends.[1] The spear is dual pointed to provide a spare, in case the first is broken off.[1] The spear-shaft measured three metres, 13–14 feet long, in length.[1]

Made of cornel wood.[1] The recorded weight, per cubic metre, of the cornel wood would be 51.5 lbs (2.34 kg) and, per cubic inch, would weigh .03 lb (.014 kg).[1]

The wood tapered at the ends, to fit into the iron spear heads at either end.[1] The middle of the spear is thinner that the out edges, giving the spear the impression of a concave shape.[1]

Materials

Cornus Mas (Wood)

Cornus Mas, also known as the cornelian cherry, is common in the wood mountains that surround Macedonia, ranging from areas in the Balkans and into Syria; specific locations were Mt. Olympus, Phthiotis, Aetolia, Arcadia, Laconis.[1]

This cornel wood was used for the spear, because of its elasticity and hardness, making it very durable and the best material for spears, javelins, and bows.[1] The other woods could not compare to the properties of cornel wood.[1] The wood, despite being used for a spear that was so long, was able to withstand the weight of itself; it was tough enough to not need thickness to balance the weight of its length.[1]

Cornus Mas became so valued and widely used, that in the fourth and third centuries it was used in poetry to note the word spear.[1]

Advantages

Phalanx

The ‘Foot Companions’, also known as the pezhetairos, utilised this spear and its length provided Macedonians with the opportunity to strike first, when in battle.[2] Alexander The Great forged the pezhetairos, who he had high influence over. He would go forth into battle armed only with his spear, the xyston, and they would too.[3]

In battle, the spear was advantageous. It was longer than a javelin, providing much deeper defence against the Persians.[4] The spear prevented the opposition from moving beyond the point of the spear, preventing hand-to-hand combat, which Persians preferred.[4] The Persians accustomed themselves more to javelins and used them as offensive throwing spears, instead of for defensive purposes.[4]

In contrast to their Greek counterparts, the Macedonian Phalanx did not rely on great expressions of bravery and country pride but on the tight formation of soldiers engineered to be the best possible fighters on the battlefield.[5] It was necessary for their survival against armies that were all brawn and no brain. This professional attitude of these soldiers was common among Macedonians and succeeded in focusing on the power of the whole, rather than the might of the individual.[5]

The intense training of these soldiers is a central reason for their strong commitment on the battlefield, which King Philip II, Alexander The Great's father, enforced into his men.[5] There were 30 mile marches, in full uniform, to best perfect their prowess. The uniform included their armour, adding more weight to their bodies, and their spear.[5]

Philip II set a solid foundation for his son, Alexander, who added additional drills and exercises to fine tune the soldiers that fought for Macedon.[5]

Cavalry

Macedonia possessed a skilled cavalry.[2] The cavalry did not require typical saddles or stirrups and they used the xyston spear as their chosen weapon.[2] Swords were only used as a last resort.[2]

Alexander's cavalry, as well as Alexander himself, used violence means of fighting to assert dominance in battle.[4] The soldiers used the xyston to pierce faces and upper bodies of enemies, instead of lower limbs and torso areas. They were utilising their high position to their advantage.[4]

There was a group of cavalry that were called the Hetairoi.[3] This group of men were a representation of the political ways of Macedon, where it centred the King. These men were descendants of noble houses, deemed elite in society, and numbered around 1,800.[3] This elite ‘hammer’ of the Macedonian army viewed themselves highly and paraded their uniforms whenever they had the chance to do so. They were adorned in purple cloaks, brimmed with golden edges, elevating their presumed importance.[3] These men were equipped with the xyston spear, which were made with a sturdy cornel wood.[3] It was Alexander that inspired these men, because of his bravado on the battlefield, to go without their cuirass and venture into battle with just their tunics and their spears.[3]

Limitations

The downside to a Cavalry is horses can be easily frightened.[6] They have a “fight or flight” response, due to their position as prey and not predator. The natural instincts of a horse would take over, giving the animal a differing reaction to battle, in comparison to their rider who can resist such instincts.[6] Alexander The Great had to adapt his battle strategy because of this when fighting in the Battle of Hydaspes, as the enemy used elephant mounts.[6]

When the opposition was able to insert themselves beyond the point of the spear, getting closer to the Macedonian soldiers, then opponents were able to overcome them. Close combat was not preferred for those using xyston spears.[4]

When the spear is shattered, it can leave the soldier open to attack and vulnerable. The wood has the potential to be an easy target if the user is overwhelmed by the enemy.[4]

The spear was a two handed weapon.[1] It was held at the midpoint of the wooden shaft, instead of a typical lance, which was held just beyond that and this was due to the heavier weight of the spear.[4] Holding it in the middle required the soldier to have more control of his hold. Macedonian soldiers, when on extra-combat missions, would not use the spear in close confrontations, they would use a javelin.[1] The spear, being too long would prevent speed and would be a nuisance, in the case of any sudden fighting that took place.

The Cavalry could push the spare spike into the ground and use the ground to reinforce the spear as a means to injure the incoming opposition, but simple mathematics contradicts this statement.[4] A rider would find it difficult to remained balanced with the proposed angle at which the spear needs to enter the ground to provide effective reinforcement.[4]

History of use

The Battle of Issus

This is the battle depicted in the infamous Alexander mosaic that resides in the Naples National Archeological Museum.[7] The mosaic is a floor mosaic and was originally found in Pompeii, in the House of the Faun.[7] It depicts Alexander the Great opposing the Persian King Darius III. Alexander is shown in the mosaic to be wielding the xyston spear, as it depicts the approximate length of the weapon.[8]

Alexander The Great was ill during this battle.[9] He had bathed in the River Cydnus before his campaign further into Persian; upon reaching Issus, the illness had lessened but still affected his performance in battle.[9] There are two accounts, Curtius and Aeschines, that contest the undergoing prior to the Battle of Issus.[9] One, that Alexander waited in the narrows of mountain paths before moving toward Darius and his troops, who were stationed at the Pillar of Jonah.[9] Two, that Alexander was in a position that could allow the Persians to easily run his army down. Alexander was a brash leader, who kept his army divided for too long and unable to secure preferred strategic positions in mountain ranges. He shows that although his instincts proved that he was an excellent tactician, he had a lot to learn regarding battle strategy.[9]

The strategy that Alexander used to hasten the battle, was to charge quickly to avoid the archers arrows flying toward him and his soldiers. The idea was to avoid more casualties by shortening the space between Persians and his army.[10]

.jpg.webp)

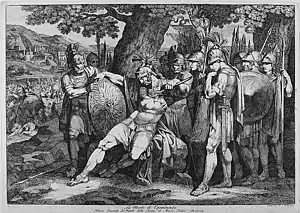

The Battle of Pydna

The battle takes its name from its geographical location, for it was fought near the plain of Pydna.[11] The location was deemed specifically chosen, by Perseus, King of Macedon in 169 BCE, for the Macedonian Army.[12] The plains were optimal for the phalanx and rolling hill, which could assist in defending any psiloi attacks.[12] Two rivers moved across the plains, providing a barrier for the Romans to cross; these rivers were not deemed as an obstacle for the Macedonian phalanx.[12]

The Paeligni, the Romans that shared the Pydna river with the Macedonians, did not prevail in this battle.[1] The Romans could not break past the Macedonian soldiers, because of their strong spear defence.[1]

The Macedonian Army caught the Romans off guard, as Aemilius, their leader, did not yet have his soldiers in line.[13] The Roman soldiers tried hard to pierce the Macedonian ranks, cut their spears with swords, or injure them with their hands but it was useless.[13] However, the tide of battle turned after the Romans found gaps in the phalanx, which was advancing over uneven ground, and used it to overpower the Macedonians, who were not able to equal the strength of the Roman gladius.[13]

At close range, the handling of the spears proved impossible, and the Macedonians could nott hold their own against the incoming Romans, ultimately losing the battle. 25,000 Macedonians were killed and 12,000 were captured.[13]

The Battle of Mantinea

This battle took place over a ditch with banks of water, which was not good for an army that relied heavily on their phalanx.[1] The terrain would give the enemy the opportunity to break through the phalanx ranks quite easily, which occurred with Lacedaemonian soldiers.[1] The spear was not a weapon that could be well used in a terrain that didn't permit a fully operational phalanx.[1]

Epaminondas wanted to pose a surprise attack on Mantinea, using his cavalry as a faster means to do so; the mission called for forces that had easy mobility.[4] This speed was necessary to retire from Mantinea if Spartan and Mantineans were to return quicker than expected.[4] This attack did not work for Epaminondas because the Spartans and Mantineans returned in a timely fashion and the cavalry was able to counter the invading cavalry.[4]

The Battle of Mantinea had no victors.[14] Everyone who took part in the battle thought they were the victors and wanted to rule over mainland Greece.[14] This led to Greek states attempting to extend their power beyond their borders and rule over others, but not one could keep a hold of their conquests for long and failed to solidify their rule.[14] This failure and confusion is what led to the welcoming of a new power in the Greek mainland, which was the Kingdom of Macedonia.[14]

Xenophon: “Everyone had supposed that the winners of this battle would be Greece's rulers and its losers their subjects; but there was only more confusion and disturbance in Greece after it than before.”[14]

The Alexander Mosaic

The mosaic is synonymous with Alexander The Great and it is the most well known mosaic to survive from Pompeii.[7] It, at the time of discovery, was a floor mosaic but is now showcased on a wall in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. It measures 2.7 x 5.2 metres.[7] It depicts the battle between the Persian King Darius III and Alexander The Great, which is known as the Battle of Issus.[7]

It was found in 1831 and represents an advancement in mosaic technology.[7] Its use of tesserae, which are small tiles cut from pieces of stone, shows historians a jump from traditional stone pebble mosaics.[7]

The Alexander Mosaic does have large parts that have been damaged over time and has left the piece unfinished, but the mosaic still has a generous impact of the viewer.[7] It is seen in the mosaic that Alexander and his forces are driving the Persians and their King, Darius III, forward and into a retreat.[7] The icy glare of Alexander The Great is clearly honed in on Darius III; Persians getting in the way of his attack.[7] A soldier is seen crushed underneath everyone, he is looking into his reflection in a shield as he is crushed.[7]

“The quality of the work and the astonishing use of light, foreshortening, and details brings home to us again how much of major Greek painting must have been lost.” - William R. Biers[15]

See also

- Ancient Macedonian military

- Companion cavalry

- Dory (spear)

- Hellenistic armies

- Kontos

- Pole weapon

- Sarissa

References

- Markle, Minor M. (1977). "The Macedonian Sarissa, Spear, and Related Armor". American Journal of Archaeology. 81 (3): 323–339. doi:10.2307/503007. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 503007.

- "1. Philip of Macedon", Alexander of Macedon, 356–323 B.C., University of California Press, pp. 1–34, 2019-12-31, doi:10.1525/9780520954694-009, ISBN 978-0-520-95469-4, retrieved 2020-11-03

- M, Dattatreya; al (2017-11-30). "The Ancient Macedonian Army: 10 Things You Should Know". Realm of History. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

- Gaebel, Robert E. (2002). Cavalry Operations In The Ancient Greek World. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 91–235.

- M, Dattatreya; al (2015-09-09). "The Macedonian Phalanx: 5 Things You Should Know". Realm of History. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- Greece, Macedon and Persia : studies in social, political and military history in honour of Waldemar Heckel. Howe, Timothy,, Garvin, E. Edward (Erin Edward),, Wrightson, Graham (Graham Charles Liquorish),, Heckel, Waldemar, 1949- (Hardcover ed.). Philadelphia. 12 March 2015. ISBN 978-1-78297-924-1. OCLC 905450291.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Brouwers, Josho. "The Alexander Mosaic - Experiencing a masterpiece". Ancient World Magazine. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- Chugg, Andrew (2010). The Death of Alexander the Great: A Reconstruction of Cleitarchus. AMC Productions. pp. 14–24.

- Murison, C. (1972). Darius III and the Battle of Issus. Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte, 21(3), 399-423. Retrieved November 19, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4435274

- Nicholas G. L. Hammond. (1992). Alexander's Charge at the Battle of Issus in 333 B.C. Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte, 41(4), 395-406. Retrieved November 19, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4436258

- Hammond, N. (1984). The Battle of Pydna. The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 104, 31-47. doi:10.2307/630278

- Nutt, S., 1993. Tactical Interaction And Integration. Newcastle upon Tyne: University of Newcastle upon Tyne, p.109-111.

- Dodge, T., 2012. Hannibal: A History Of The Art Of War Among The Carthaginians And Romans Down To The Battle Of Pydna, 168 B. C.. Tales End Press.

- "Thomas R. Martin, An Overview of Classical Greek History from Mycenae to Alexander, The Aftermath of the Peloponnesian War, Stalemate after the Battle of Mantinea". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2020-11-20.

- Biers, William R. (1996). The Archaeology Of Greece. Ithaca N.Y.: Cornell University Press. pp. 319–320.