Zande people

The Azande (plural of "Zande" in the Zande language) are an ethnic group of North Central Africa.

Azande men with shields, harp, between 1877 and 1880. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3.8 million at end of 20th century[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan | |

| Languages | |

| Pa-Zande, Bangala, English, Sango and Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, African Traditional Religion |

They live primarily in the northeastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in south-central and southwestern part of South Sudan, and in southeastern Central African Republic. The Congolese Azande live in Orientale Province, specifically along the Uele River; Isiro, Dungu, Kisangani and Duruma. The Central African Azande live in the districts of Rafaï, Bangasu and Obo. The Azande of South Sudan live in Central, Western Equatoria and Western Bahr al-Ghazal States, Yei, Maridi, Yambio, Tombura, Deim Zubeir, Wau Town and Momoi.

History

The Zande were believed to be formed by a military conquest during the first half of the 18th century. They were led by two dynasties that differed in origin and political strategy. The Vungara clan created most of the political, linguistic, and cultural parts. A non-Zande dynasty, the Bandia, expanded into northern Zaire and adopted some of the Zande customs.[2] In the early 19th century, the Bandia people ruled over the Vungara and the two groups became the Azande people. They lived in the savannas of what is now the southeastern part of Central African Republic. After the death of a king, the king's sons would fight for succession. The losing son would often establish kingdoms in neighboring regions, making the Azande kingdom spread eastward and northward. Sudanese raids halted some of northward expansion later in the 19th century. The Azande became divided by Belgium, France, and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.[3]

Name

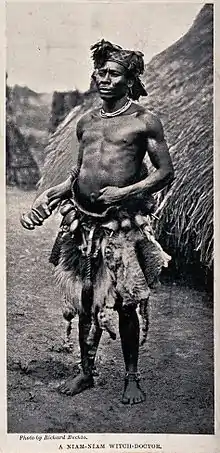

The word Azande means "the people who possess much land", and refers to their history as conquering warriors. Variant spellings include Adio, Zande, Zandeh, A-Zandeh and Sandeh. The name Niam-Niam was frequently used by foreigners to refer to the Azande in the 18th and early 19th century. This name is probably of Dinka origin, and means great eaters in that language, supposedly referring to cannibalistic propensities. This name for the Azande was in use by other tribes in South Sudan, and later adopted by westerners. Today the name Niam-Niam is considered pejorative.[4]

Language and literature

The Azande speak Zande, which they call Pa-Zande, which has an estimated 1.1 million speakers.[5] Zande is also used to refer to related languages in addition to Azande proper, including Adio, Barambu, Apambia, Geme, Kpatiri and Nzakara.

Recorded Zande literature is mostly oral, some of it published by missionaries in the early 20th century, and some of it translated in the 1960s.[6]

Demographics

The Azande population is spread over three Central African countries: South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic. Azande territory extends from the fringes of the South-central and Southwest Upper basin of South Sudan to the semitropical rain forests in Congo, and into the Central African Republic.

Estimates of Azande speakers reported in SIL Ethnologue are 730,000 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 62,000 in the Central African Republic and 350,000 in South Sudan.[5]

Settlements

The types of houses that the Azande built were made from mud and grass, which they framed around wooden poles and thatched with grass. Each household was built around a courtyard so that they can gather and converse with each other. Adjacent to these courtyards were kitchen gardens that were for plants that did not require large scale farming such as pineapples and mangos.[7]

Social and political organizations

The Azande were organized into chiefdoms that can also be called kingdoms. The Avongara were the nobility and passed it down through their lineage. Chiefs had many roles within the chiefdoms such as being military, economic, and political leaders. All the unmarried men were laborers and warriors.[7]

Within the chiefdoms clan affiliation was not stressed as important at the local level. They had “local groups” that were similar to “political organizations”.[7]

Agriculture

After World War II, the British government tried to encourage cotton cultivation in southern Sudan in a program known as the Zande Scheme. The program largely failed, partly because of the Azande's relative isolation to trading ports. Because of this isolation, many Azande have moved to towns closer to major roads.[8]

The Azande are mainly small-scale farmers. Crops include maize, rice, groundnuts (also known as peanuts), sesame, cassava and sweet potatoes. Fruits grown in the area include mangos, oranges, bananas, pineapples, and also sugar cane. Zandeland is also full of palm oil and sesame. From 1998 to 2001, Zande agriculture was boosted since World Vision International bought agricultural produce.

Since then, the Azande have hunted and farmed millet, sorghum, and corn. Major cash crops include cassava and peanuts.[8]

The region in which the Azande live has two seasons. During the rainy season the women and men both help get food from the river. Women help with the fishing in dammed streams and shallow pools collecting fish, snakes, and crustaceans. Men make and set up traps in the river to help with the collection of food. Another food that the Azande collect and eat is termites which are their favorites.[7]

Art

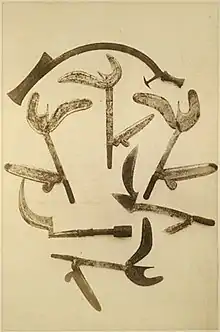

Art is a key part of Zande culture. They are most famously known for their throwing knife called the "shongo". It shows the skill of Zande metal workers with its curved and multi-bladed features. More of their art included sculptures made from wood or clay. Many represented animals or ancestors important in their culture. Just like their sculptures, they also created thumb pianos, Sansas, that looked like people, animals, and abstract figures. These instruments were used at important celebrations: marriages and ceremonial dances.[9]

Traditional beliefs

Religion

Most Azande formerly practised a traditional African religion, but this has been supplanted to a large extent by Christianity. Their traditional religion involves belief in Mboli, an omnipotent god.[10] They practice magic, oracles, and witchcraft in order to solve their everyday problems.[11] However, the late-nineteenth century marked the beginning of many Zande converting to Christianity. 85 percent of Azande consider them self Christian, while 15 percent follow their traditional religion. More than half of Azande identify as Roman Catholic.[10]

Witchcraft

Other traditional beliefs include magic and witchcraft. Among the Azande, witchcraft, or mangu, is believed to be an inherited black fluid in the belly which leads a fairly autonomous existence, and has power to perform bad magic on one's enemies. Since they believed that witchcraft is inherited, an autopsy of an accused witch would also prove that a particular living person, related to the deceased, was or was not a witch. Mangu is thought to be passed down from parent to child of the same sex — from father to son or from mother to daughter. Therefore if a man were to be proven to possess witchcraft substance, this conclusion would extend to that man's father, sons, brothers, and so on.

The Azande rarely have a theoretical interest in witchcraft. What is important is whether a person at a particular point in time is acting as a witch toward a specific person.[12] Witches can sometimes be unaware of their powers, and can accidentally strike people to whom the witch wishes no evil. In terms of death, the prince determined the vengeance placed on the witch or the killer. This could be done through physical killing of the witch, compensation, or lethal magic.[13]

Because witchcraft is believed always to be present, there are several rituals connected to protection from and cancelling of witchcraft that are performed almost daily. When something out of the ordinary occurs, usually something unfortunate, to an individual, the Azande may blame witchcraft, just as non-Zande people might blame "bad luck".

Although witchcraft is contained within the physical body, its action is psychic. The psychic aspect of mangu is the soul of witchcraft. It usually, but not always, leaves the physical body of the witch at night, when the victim is asleep, and is directed by the witch into the body of the victim. As it moves, it shines with a bright light that can be seen by anyone during the nighttime. However, during the day it can be seen only by religious specialists.[12]

Oracles are a way of determining the source of the suspected witchcraft, and were for a long time the ultimate legal authority and the main determining factor in how one would respond to the threats. The Azande use three different types of oracles. The most powerful oracle is the “benge” poison oracle, which is used solely by men. The decisions of the oracle are always accepted and no one questions it. The less prestigious but more readily available is the termite oracle. Women, men, and children are all allowed to consult this oracle. The least expensive but also least reliable oracle is the rubbing-board oracle. The rubbing board oracle is described in Culture Sketches as “a device resembling a Ouija board, made of two small pieces of wood easily carried to be consulted anywhere, and at any time.” [14]

Relationships among young men

There was also a social institution similar to pederasty in Ancient Greece. As E. E. Evans-Pritchard recorded in the northern Congo, male Zande warriors between 20 and 30 years of age routinely took on young male lovers between the ages of twelve and twenty, who participated in intercrural sex and sex with their older partners. The practice largely died out by the mid-19th century, after imperialist Europeans had gained colonial control of African countries, but was still surviving to sufficient degree that the practice was recounted in some detail to Evans-Pritchard by the elders with whom he spoke.[15]

Relationships among young women

During the 1930s Evans-Pritchard recorded information about sexual relationships between women, based on reports from male Azande.[16]:55 According to male Azande, women would take female lovers in order to seek out pleasure and that partners would penetrate each other using bananas or a food item carved into the shape of a phallus.[16]:55 They also reported that the daughter of a ruler may be given a female slave as a sexual partner.[16]:55 Evans-Pritchard also recorded that the male Azande were fearful of women taking on female lovers, as they might view men as unnecessary.[16]:55–56

Gallery

Zande throwing knives

Zande throwing knives Zande woman in late 1870s with skin markings

Zande woman in late 1870s with skin markings Azande warriors

Azande warriors Vassel from the 20th century

Vassel from the 20th century

Notes

- Zande, Encyclopedia Britannica

- "Azande". www.sscnet.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony; Gates Jr., Henry Louis, eds. (2005). "Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience". Africana. 1 (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 315. ISBN 9780195170559.

- Kramer, Robert S.; Lobban, Richard Andrew; Fluehr-Lobban, Carolyn (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Sudan. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-6180-0.

- Zande in: Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International.

Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2018). "Zande". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (21st ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Retrieved 2018-06-29. - Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1965). "Some Zande Animal Tales from the Gore Collection". Man. 65: 70–77. doi:10.2307/2797214. JSTOR 2797214.

- Holly., Peters-Golden (2012). Culture sketches : case studies in anthropology (6th ed.). Dubuque, Iowa: The McGraw-Hill. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9780078117022. OCLC 716069710.

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony; Gates Jr., Henry Louis, eds. (2005). "Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience". Africana. 1 (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 315. ISBN 9780195170559.

- Schmermund, E. M. (2020). Zande people. Salem Press Encyclopedia.

- Schmermund, E. M. (2020). Zande people. Salem Press Encyclopedia.

- Singer, Andre (1981). "Alexander Street, a ProQuest Company". video.alexanderstreet.com. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- Stein, Rebecca L.; Stein, Philip L. (2016). The Anthropology of Religion, Magic, and Witchcraft (3rd ed.). London: Routledge. p. 214. ISBN 9780205718115. OCLC 928384577.

- Costa, Newton da; French, Steven (1995). "Partial Structures and the Logic of Azande". American Philosophical Quarterly. 32 (4): 325–339. ISSN 0003-0481.

- Singer, André (1981). "Witchcraft among the Azande". johnryle.com. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- E. E. Evans-Pritchard (December, 1970). "Sexual Inversion among the Azande". American Anthropologist, (New Series) 72 (6), 1428-1434.

- Rupp, Leila J. (2009-12-01). Sapphistries: A Global History of Love between Women. NYU Press. ISBN 9780814776445.

Zande.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1979) "Witchcraft Explains Unfortunate Events" in William A. Lessa and Evon Z. Vogt (eds.) Reader in Comparative Religion. An anthropological approach. Fourth Edition. New York: Harper Collins Publishers. pp. 362–366

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1967) The Zande Trickster. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1937) Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande. Oxford University Press. 1976 abridged edition: ISBN 0-19-874029-8

- Homosexuality in African History." Rainbow Sudan , Sudan Magazine , 10 May 2014, rainbowsudan.wordpress.com/tag/the-azande-plural-of-zande-in-the-zande-language-are-a-ethnic-group-of-north-central-africa/. Accessed 27 Nov. 2018.

- Rupp, Leila. Sapphistries: A Global History of Love between Women. New York, New York University Press, 2009, pp. 23–56.

- Lewin, Ellen, editor. Feminist Anthropology: A Reader. Carlton, Blackwell Publishing, 2006, pp. 67–68.

- Schildkrout, Enid. (1999). Gender and Sexuality in Mangbetu Art. 205.