Kongo people

The Kongo people (Kongo: Esikongo, singular: MwisiKongo; also Bakongo, singular: Mukongo)[2] are a Bantu ethnic group primarily defined as the speakers of Kikongo (Kongo languages).[3]

_(14597123707).jpg.webp) A Kongo woman's cast from 1910 by Herbert Ward | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 17,254,808[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Native languages: Kikongo Lingala (minority) Second languages: French (DR Congo, Congo, Gabon) Portuguese (Angola) | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Kongo religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Basuku, Yaka and other Bantu peoples |

| Kongo | |

|---|---|

| Person | Mwisikongo, Mukongo |

| People | Esikongo, Bakongo |

| Language | Kikongo |

| Country | Kongo dia Ntotila (or Ntotela), Loango, Ngoyo and Kakongo |

They have lived along the Atlantic coast of Central Africa, in a region that by the 15th century was a centralized and well-organized Kingdom of Kongo, but is now a part of three countries.[4] Their highest concentrations are found south of Pointe-Noire in the Republic of the Congo, southwest of Pool Malebo and west of the Kwango River in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, north of Luanda, Angola and southwest Gabon.[3] They are the largest ethnic group in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and one of the major ethnic groups in the other two countries they are found in.[4] In 1975, the Kongo population was reported as 4,040,000.[5]

The Kongo people were among the earliest sub-Saharan Africans to welcome Portuguese traders in 1483 CE, and began converting to Catholicism in the late 15th century.[4] They were among the first to protest slavery in letters to the King of Portugal in the 1510s and 1520s,[6][7] then succumbed to the demands for slaves from the Portuguese through the 16th century. The Kongo people were a part of the major slave raiding, capture and export trade of African slaves to the European colonial interests in 17th and 18th centuries.[4] The slave raids, colonial wars and the 19th-century Scramble for Africa split the Kongo people into Portuguese, Belgian and French parts. In the early 20th century, they became one of the most active ethnic groups in the efforts to decolonize Africa, helping liberate the three nations to self governance. They now occupy influential positions in the politics, administration and business operations in the three countries they are most found in.[4]

Name

The origin of the name Kongo is unclear, and several theories have been proposed.[8] According to the colonial era scholar Samuel Nelson, the term Kongo is possibly derived from a local verb for gathering or assembly.[9] According to Alisa LaGamma, the root may be from the regional word Nkongo which means "hunter" in the context of someone adventurous and heroic.[10] Douglas Harper states that the term means "mountains" in a Bantu language, which the Congo river flows down from.[11]

The Kongo people have been referred to by various names in the colonial French, Belgian and Portuguese literature, names such as Esikongo (singular Mwisikongo), Mucicongo, Mesikongo, Madcongo and Moxicongo.[8] Christian missionaries, particularly in the Caribbean, originally applied the term Bafiote (singular M(a)fiote) to the slaves from the Vili or Fiote coastal Kongo people, but later this term was used to refer to any "black man" in Cuba, St Lucia and other colonial era Islands ruled by one of the European colonial interests.[12] The group is identified largely by speaking a cluster of mutually intelligible dialects rather than by large continuities in their history or even in culture. The term "Congo" was more widely deployed to identify Kikongo-speaking people enslaved in the Americas.[13]

Since the early 20th century, Bakongo (singular Mkongo or Mukongo) has been increasingly used, especially in areas north of the Congo river, to refer to the Kikongo-speaking community, or more broadly to speakers of the closely related Kongo languages.[2] This convention is based on the Bantu languages, to which Kongo language belongs. The prefix "mu-" and "ba-" refer to "people", singular and plural respectively.[14]

Ne in Kikongo designates a title, it is incorrect to call Kongo people by Ne Kongo or a Kongo person by Ne Kongo.[15]

History

The ancient history of the Kongo people has been difficult to ascertain. The region is close to East Africa, considered to be a key to the prehistoric human migrations. This geographical proximity, states Jan Vansina, suggests that the Congo river region, home of the Kongo people, was populated thousands of years ago.[16] Ancient archeological evidence linked to Kongo people has not been found, and glottochronology – or the estimation of ethnic group chronologies based on language evolution – has been applied to the Kongo. Based on this, it is likely the Kongo language and Gabon-Congo language split about 950 BCE.[16]

The earliest archeological evidence is from Tchissanga (now part of modern Republic of the Congo), a site dated to about 600 BCE. However, the site does not prove which ethnic group was resident at that time.[16] The Kongo people had settled into the area well before the fifth century CE, begun a society that utilized the diverse and rich resources of region and developed farming methods.[17] According to James Denbow, social complexity had probably been achieved by the second century CE.[18]

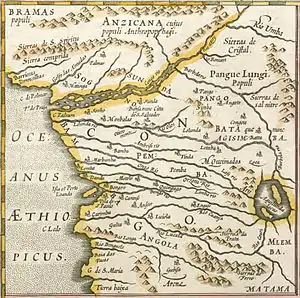

According to Vansina small kingdoms and Kongo principalities appeared in the current region by the 1200 CE, but documented history of this period of Kongo people if it existed has not survived into the modern era. Detailed and copious description about the Kongo people who lived next to the Atlantic ports of the region, as a sophisticated culture, language and infrastructure, appear in the 15th century, written by the Portuguese explorers.[19] Later anthropological work on the Kongo of the region come from the colonial era writers, particularly the French and Belgians (Loango, Vungu, and the Niari Valley), but this too is limited and does not exhaustively cover all of the Kongo people. The evidence suggests, states Vansina, that the Kongo people were advanced in their culture and socio-political systems with multiple kingdoms well before the arrival of first Portuguese ships in the late 15th century.[19]

The Kingdom of Kongo

Kongo oral tradition suggests that the Kingdom of Kongo was founded before the 14th century and the 13th century.[20][21][22] The kingdom was modeled not on hereditary succession as was common in Europe, but based on an election by the court nobles from the Kongo people. This required the king to win his legitimacy by a process of recognizing his peers, consensus building as well as regalia and religious ritualism.[23] The kingdom had many trading centers both near rivers and inland, distributed across hundreds of kilometers and Mbanza Kongo – its capital that was about 200 kilometers inland from the Atlantic coast.[23]

The Portuguese arrived on the Central African coast north of the Congo river, several times between 1472 and 1483 searching for a sea route to India,[23] but they failed to find any ports or trading opportunities. In 1483, south of the Congo river they found the Kongo people and the Kingdom of Kongo, which had a centralized government, a currency called nzimbu, and markets, ready for trading relations.[24] The Portuguese found well developed transport infrastructure inlands from the Kongo people's Atlantic port settlement. They also found exchange of goods easy and the Kongo people open to ideas. The Kongo king at that time, named Nzinga a Nkuwu allegedly willingly accepted Christianity, and at his baptism in 1491 changed his name to João I, a Portuguese name.[23] Around the 1450s, a prophet, Ne Buela Muanda, predicted the arrival of the Portuguese and the spiritual and physical enslavement of many Bakongo.[25][26]

The trade between Kongo people and Portuguese people thereafter accelerated through 1500. The kingdom of Kongo appeared to become receptive of the new traders, allowed them to settle an uninhabited nearby island called São Tomé, and sent Bakongo nobles to visit the royal court in Portugal.[24] Other than the king himself, much of the Kongo people's nobility welcomed the cultural exchange, the Christian missionaries converted them to the Catholic faith, they assumed Portuguese court manners, and by early 16th-century Kongo became a Portugal-affiliated Christian kingdom.[4]

Start of slavery

Initially, the Kongo people exchanged ivory and copper objects they made with luxury goods of Portuguese.[24] But, after 1500, the Portuguese had little demand for ivory and copper, they instead demanded slaves in exchange. The settled Portuguese in São Tomé needed slave labor for their sugarcane plantations, and they first purchased labor. Soon thereafter they began kidnapping people from the Kongo society and after 1514, they provoked military campaigns in nearby African regions to get slave labor.[24] Along with this change in Portuguese-Kongo people relationship, the succession system within Kongo kingdom changed under Portuguese influence,[27] and in 1509, instead of the usual election among the nobles, a hereditary European-style succession led to the African king Afonso I succeeding his father, now named João I.[24] The slave capture and the export of slaves caused major social disorder among the Kongo people, and the Kongo king Afonso I wrote letters to the king of Portugal protesting this practice. Finally, he succumbed to the demand and accepted an export of those who willing accepted slavery, and for a fee per slave. The Portuguese procured 2,000 to 3,000 slaves per year for a few years, from 1520, a practice that started the slave export history of the Kongo people. However, this supply was far short of the demand for slaves and the money slave owners were willing to pay.[24]

The Portuguese operators approached the traders at the borders of the Kongo kingdom, such as the Malebo Pool and offered luxury goods in exchange for captured slaves. This created, states Jan Vansina, an incentive for border conflicts and slave caravan routes, from other ethnic groups and different parts of Africa, in which the Kongo people and traders participated.[24] The slave raids and volume of trade in enslaved human beings increased thereafter, and by the 1560s, over 7,000 slaves per year were being captured and exported by Portuguese traders to the Americas.[24] The Kongo people and the neighboring ethnic groups retaliated, with violence and attacks, such as the Jaga invasion of 1568 which swept across the Kongo lands, burnt the Portuguese churches, and attacked its capital, nearly ending the Kingdom of Kongo.[24][28] The Kongo people also created songs to warn themselves of the arrival of the Portuguese, one of the famous songs is " Malele " (Translation: "Tragedy", song present among the 17 Kongo songs sung by the Massembo family of Guadeloupe during the Grap a Kongo [29]). The Portuguese brought in military and arms to support the Kingdom of Kongo, and after years of fighting, they jointly defeated the attack. This war unexpectedly led to a flood of captives who had challenged the Kongo nobility and traders, and the coastal ports were flooded with "war captives turned slaves".[24] The other effect of this violence over many years was making the Kongo king heavily dependent on the Portuguese protection,[27] along with the dehumanization of the African people, including the rebelling Kongo people, as cannibalistic pagan barbarians from "Jaga kingdom". This caricature of the African people and their dehumanization was vociferous and well published by the slave traders, the missionaries and the colonial era Portuguese historians, which helped morally justify mass trading of slaves.[24][28]

Modern scholars such as Estevam Thompson suggest that the war was a response of the Kongo people and other ethnic groups to the stolen children and broken families from the rising slavery, because there is no evidence that any "Jaga kingdom" ever existed, and there is no evidence to support other related claims alleged in the records of that era.[28][30] The 16th and 17th centuries' one-sided dehumanization of the African people was a fabrication and myth created by the missionaries and slave trading Portuguese to hide their abusive activities and intentions, state Thompson[28] and other scholars.[30][31][32]

From the 1570s, the European traders arrived in large numbers and the slave trading through the Kongo people territory dramatically increased. The weakened Kingdom of Kongo continued to face internal revolts and violence that resulted from the raids and capture of slaves, and the Portuguese in 1575 established the port city of Luanda (now in Angola) in cooperation with a Kongo noble family to facilitate their military presence, African operations and the slave trade thereof.[33][34] The Kingdom of Kongo and its people ended their cooperation in the 1660s. In 1665, the Portuguese army invaded the Kingdom, killed the Kongo king, disbanded his army, and installed a friendly replacement in his place.[35]

Smaller kingdoms

The 1665 Kongo-Portuguese war and the killing of the hereditary king by the Portuguese soldiers led to a political vacuum. Kongo kingdom disintegrated into smaller kingdoms, each controlled by nobles considered friendly by the Portuguese.[4] One of these kingdoms was the kingdom of Loango. The Loango was in the northern part, above the Congo river, a region which long before the war was already an established community of the Kongo people.[24] New kingdoms came into existence in this period, from the disintegrated parts in the southeast and the northeast of the old Kongo kingdom. The old capital of Kongo people called Sao Salvador was burnt down, in ruins and abandoned in 1678.[36] The fragmented new kingdoms of Kongo people disputed each other's boundaries and rights, as well as of other non-Kongo ethnic groups bordering them, leading to steady wars and mutual raids.[4][37]

The wars between the small kingdoms created a steady supply of captives that fed the Portuguese demand for slaves and the small kingdom's need for government income to finance the wars.[39][40] In the 1700s, a baptized teenage Kongo woman named Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita claimed to be possessed by Saint Anthony of Padua and that she has been visiting heaven to speak with God.[40] She started preaching that Mary and Jesus were not born in Nazareth but in Africa among the Kongo people. She created a movement among the Kongo people which historians call as Kongo Antonianism.[41]

Dona Beatriz questioned the wars devastating the Kongo people, asked all Kongo people to end the wars that fed the trading in humans, unite under one king.[4][38] She attracted a following of thousands of Kongo people into the ruins of their old capital. She was declared a false saint by the Portuguese appointed Kongo king Pedro IV, with the support of Portuguese Catholic missionaries and Italian Capuchin monks then resident in Kongo lands. The 22 year old Dona Beatriz was arrested, then burnt alive at the stake on charges of being a witch and a heretic.[4][42]

Colonial era

After the death of Dona Beatriz in 1706 and another three years of wars with the help of the Portuguese, Pedro IV was able to get back much of the old Kongo kingdom.[4] The conflicts continued through the 18th century, however, and the demand for and the caravan of Kongo and non-Kongo people as captured slaves kept rising, headed to the Atlantic ports.[36] Although, in Portuguese documents, all of Kongo people were technically under one ruler, they were no longer governed that way by the mid-18th century. The Kongo people were now divided into regions, each headed by a noble family. Christianity was growing again with new chapels built, services regularly held, missions of different Christian sects expanding, and church rituals a part of the royal succession. There were succession crises, ensuing conflicts when a local royal Kongo ruler died and occasional coups such as that of Andre II by Henrique III, typically settled with Portuguese intervention, and these continued through the mid 19th-century.[36] After Henrique III died in 1857, competitive claims to the throne were raised by his relatives. One of them, Pedro Elelo, gained the trust of Portuguese military against Alvero XIII, by agreeing to be vassal of the colonial Portugal. This effectively ended whatever sovereignty had previously been recognized and the Kongo people became a part of colonial Portugal.[43]

| Region | Total embarked | Total disembarked |

|---|---|---|

| Kongo people region | 5.69 million | |

| Bight of Biafra | 1.6 million | |

| Bight of Benin | 2.00 million | |

| Gold Coast | 1.21 million | |

| Windward Coast | 0.34 million | |

| Sierra Leone | 0.39 million | |

| Senegambia | 0.76 million | |

| Mozambique | 0.54 million | |

| Brazil (South America) | 4.7 million | |

| Rest of South America | 0.9 million | |

| Caribbean | 4.1 million | |

| North America | 0.4 million | |

| Europe | 0.01 million |

In concert with the growing import of Christian missionaries and luxury goods, the slave capture and exports through the Kongo lands grew. With over 5.6 million human beings kidnapped in Central Africa, then sold and shipped as slaves through the lands of the Kongo people, they witnessed the largest exports of slaves from Africa into the Americas by 1867.[44] According to Jan Vansina, the "whole of Angola's economy and its institutions of governance were based on the slave trade" in 18th and 19th century, until the slave trade was forcibly brought to an end in the 1840s. This ban on lucrative trade of slaves through the lands of Kongo people was bitterly opposed by both the Portuguese and Luso-Africans (part Portuguese, part African), states Vansina.[46] The slave trade was replaced with ivory trade in the 1850s, where the old caravan owners and routes replaced hunting human beings with hunting elephants for their tusks with the help of non-Kongo ethnic groups such as the Chokwe people, which were then exported with the labor of Kongo people.[46]

Swedish missionaries entered the area in the 1880s and 1890, converting the northeast section of Kongo to Protestantism in the early twentieth century. The Swedish missionaries, notably Karl Laman, encouraged the local people to write their history and customs in notebooks, which then became the source for Laman's famous and widely cited ethnography and their dialect became well established thanks to Laman's dictionary of Kikongo.[47]

The fragmented Kongo people in the 19th century were annexed by three European colonial empires, during the Scramble for Africa and Berlin Conference, the northernmost parts went to France (now the Republic of Congo and Gabon), the middle part along river Congo along with the large inland region of Africa went to Belgium (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) and the southern parts (now Angola) remained with Portugal.[48] The Kongo people in all three colonies (Angola, the Republic of Congo and the Democratic Republic of Congo) became one of the most active ethnic groups in the efforts to decolonize Africa, and worked with other ethnic groups in Central Africa to help liberate the three nations to self governance.[4] The French and Belgium regions became independent in 1960. Angolan independence came in 1975.[49][50] The Kongo people now occupy influential positions in the politics, administration and business operations in the three countries they are most found in.[4]

Language and demographics

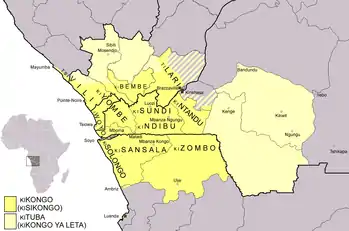

The language of the Kongo people is called Kikongo (Guthrie: Bantu Zone H.10). It is a macrolanguage and consists of Beembe, Doondo, Koongo, Laari, Kongo-San-Salvador, Kunyi, Vili and Yombe sub-languages.[51] It belongs to the Niger-Congo family of languages, more specifically the southern Bantu branch.[52]

The Kongo language is divided into many dialects which are sufficiently diverse that people from distant dialects, such as speakers of Kivili dialect (on the northern coast) and speakers of Kisansolo (the central dialect) would have trouble understanding each other.

In Angola, there are a few who did not learn to speak Kikongo because Portuguese rules of assimilation during the colonial period was directed against learning native languages, though most Bakongo held on to the language. Most Angolan Kongo also speak Portuguese and those near the border of the Democratic Republic of Congo also speak French. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo most also speak French and others speak either Lingala, a common lingua franca in Western Congo, or Kikongo ya Leta (generally known as Kituba particularly in the Republic of the Congo), a creole form of Kikongo spoken widely in the Republic of the Congo and in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Religion

The religious history of the Kongo is complex, particularly after the ruling class of the Kingdom of Kongo accepted Christianity at the start of the 16th century. According to historian John K. Thornton "Central Africans have probably never agreed among themselves as to what their cosmology is in detail, a product of what I called the process of continuous revelation and precarious priesthood."[53] The Kongo people had diverse views, with traditional religious ideas best developed in the small northern Kikongo-speaking area, and this region neither converted to Christianity nor participated in slave trade until the 19th century.[53]

There is abundant description about Kongo people's religious ideas in the Christian missionary and colonial era records, but states Thornton, these are written with a hostile bias and their reliability is problematic.[54] The Kongo people's beliefs included Kilundu as Nzambi (god) or Jinzambi (gods, deities), all of which had limited powers. They believed in a creator absolute god, which the 16th-century Christian missionaries to Kongo stressed is same as the Christian God, to help spread their ideas by embracing the old Kongo people's ideas.[55] Similarly, the early missionaries used Kongo language words to integrate Christian ideas, such as using the words "nkisi" to mean "holy". Thus, states Thornton, church to Kongo people was "nzo a nkisi" or another shrine, and the Bible was "mukanda nkisi" or a charm.[56] Kongo people maintained both churches and shrines, which they called Kiteki. Their smaller shrines were dedicated to the smaller deities, even after they had converted to Christianity.[55] These deities were guardians of water bodies, crop lands and high places to the Kongo people, and they were very prevalent both in capital towns of the Christian ruling classes, as well as in the villages.[55]

The later Portuguese missionaries and Capuchin monks upon their arrival in Kongo were baffled by these practices in the late 17th century (nearly 150 years after the acceptance of Christianity as the state religion in the Kingdom of Kongo). Some threatened to burn or destroy the shrines down. However, the Kongo people credited these shrines for abundance and defended them.[55] The Kongo people's conversion was based on different assumptions and premises about what Christianity was, and syncretic ideas continued for centuries.[57]

The Kongo people, state the colonial era accounts, included a reverence for their ancestors and spirits.[58] Only Nzambi a Mpungu, the name for the high god, is usually held to have existed outside the world and to have created it. Other categories of the dead include bakulu or ancestors (the souls of the recently departed). In addition, the traditional Kongo belief considered fierce looking Nkisi as guardians of particular places, such as mountains, river courses, springs and districts, called simbi (pl. bisimbi).

However, some anthropologists report regional differences. According to Dunja Hersak, for example, the Vili and Yombe do not believe in the power of ancestors in the same degree as to those living farther south. Furthermore, she and John Janzen state that religious ideas and emphasis have changed over time.[59][60]

The slaves brought over by the European ships into the Americas carried with them their traditional ideas. Vanhee suggests that the Afro-Brazilian Quimbanda religion is a new world manifestation of Bantu religion and spirituality, and Kongo Christianity played a role in the formation of Voudou in Haiti.[61]

Society and culture

The large Bakongo society features a diversity of occupations. Some are farmers who grow staples and cash crops. Among the staples are cassava, bananas, maize, taro and sweet potatoes. Other crops include peanuts (groundnuts) and beans.[3] The cash crops were introduced by the colonial rulers, and these include coffee and cacao for the chocolate industry. Palm oil is another export commodity, while the traditional urena is a famine food. Some Kongo people fish and hunt, but most work in factories and trade in towns.[3]

The Kongo people have traditionally recognized their descent from their mother (matrilineality), and this lineage links them into kinship groups.[3][62] They are culturally organized as ones who cherish their independence, so much so that neighboring Kongo people's villages avoid being dependent on each other. There is a strong undercurrent of messianic tradition among the Bakongo, which has led to several politico-religious movements in the 20th century.[3] This may be linked to the premises of dualistic cosmology in Bakongo tradition, where two worlds exist, one visible and lived, another invisible and full of powerful spirits. The belief that there is an interaction and reciprocal exchange between these, to Bakongo, means the world of spirits can possess the world of flesh.[62]

Article about Kongo clans

Article about Vili clans

The Kongo week was a four-day week: Konzo, Nkenge, Nsona and Nkandu.[63] These days are named after the four towns near which traditionally a farmer's market was held in rotation.[63] This idea spread across the Kongo people, and every major district or population center had four rotating markets locations, each center named after these days of the week. Larger market gatherings were rotated once every eight days, on Nsona Kungu.[64]

Nationalism

The idea of a Bakongo unity, actually developed in the early twentieth century, primarily through the publication of newspapers in various dialects of the language. In 1910 Kavuna Kafwandani (Kavuna Simon) published an article in the Swedish mission society's Kikongo language newspaper Misanü Miayenge (Words of Peace) calling for all speakers of the Kikongo language to recognize their identity.[65]

The Bakongo people have championed ethnic rivalry and nationalism through sports such as football. The game is organized around ethnic teams, and fans cheer their teams along ethnic lines, such as during matches between the Poto-Poto people and the Kongo people. Further, during international competitions, they join across ethnic lines, states Phyllis Martin, to "assert their independence against church and state".[66]

See also

- Kimpa Vita, a 17th-century Kongo woman who appealed for an end to wars, but was burnt at the stake for being a false saint

- Nkisi, "Sacred Medicine" that was once used primarily by the Bakongo and people of the surrounding areas.

- The Congo Village-exhibition in 1914 in Norway

Notes

- This slave trade volume excludes the slave trade by Swahili-Arabs in East Africa and North African ethnic groups to the Middle East and elsewhere. The exports and imports do not match, because of the large number of deaths en route[45] and violent retaliation by captured people on the ships involved in the slave trade.[44]

References

- 40,5% of Rep of the Congo's population, 13% of Angola's population, 12% of DRC's population and 20 000 inhabitants of Gabon (Worldometers and CIA.gov).

- Thornton, J. K. (2000). "Mbanza Kongo / São Salvador". In Anderson (ed.). Africa's Urban Past. p. 79, note 2.

...since about 1910 it is not uncommon for the term Bakongo (singular Mukongo) to be used, especially in areas north of the Zaire river, and by intellectuals and anthropologists adopting a standard nomenclature for Bantu-speaking peoples.

- "Kongo people". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Appiah, Anthony; Henry Louis Gates (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- See Redinha, José (1975). Etnias e culturas de Angola. Luanda: Instituto de Investigação Científica de Angola.

- Page, Melvin (2003). Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 773. ISBN 978-1-57607-335-3.

- Shillington, Kevin (2013). Encyclopedia of African History (3-Volume Set). Routledge. p. 1379. ISBN 978-1-135-45670-2.

- Filippo Pigafetta; Duarte Lopes (2002). Le Royaume de Congo & les contrées environnantes. Chandeigne. pp. 273 note Page82.1. ISBN 978-2-906462-82-3.

- "It is probable that the word 'Kongo' itself implies a public gathering and that it is based on the root konga, 'to gather' (trans[itive])." Nelson, Samuel Henry. Colonialism In The Congo Basin, 1880–1940. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1994.

- LaGamma, Alisa (2015). Kongo: Power and Majesty. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-58839-575-7.

- Congo, Douglas Harper, Etymology Dictionary

- Warner-Lewis, Maureen (2003). Central Africa in the Caribbean: Transcending Time, Transforming Cultures. University of West Indies Press. pp. 320–321. ISBN 978-976-640-118-4.

- Thornton, John, Les anneaux de la Memoire, 2 (2000) 235–49. "La nation angolaise en Amérique, son identité en Afrique et en Amérique", Archived 2012-03-31 at the Wayback Machine"

- Vansina, Jan M. (1990). Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa. University of Wisconsin Press. p. xix. ISBN 978-0-299-12573-8.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt (2000). Kongo Political Culture: The Conceptual Challenge of the Particular. Indiana University Press. p. 241.

- Vansina (1990). Paths in the Rainforests. pp. 52, 47–54.

- Vansina (1990). Paths in the Rainforests. pp. 146–148.

- Denbow, James (1990). "Congo to Kalahari: Data and Hypotheses about the Political Economy of the Early Western Stream of the Bantu Expansion". African Archaeology Review. 8: 139–75. doi:10.1007/bf01116874.

- Vansina (1990). Paths in the Rainforests. pp. 152–158.

- Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau, le Mukongo et le monde qui l’entourait: cosmogonie kongo, Office National de la Recherche et de Développement, Kinshasa, 1969

- Arsène Francoeur Nganga, Les origines Kôngo d’Haïti: Première République Noire de l’Humanité, Diasporas noires, 2019

- Arte (Invitation au voyage), En Angola, au cœur du royaume Kongo, Arte, 2020

- Vansina (1990). Paths in the Rainforests. pp. 200–202.

- Thomas T. Spear and Isaria N. Kimambo, East African Expressions of Christianity, James Currey Publishers, 1999, p. 219

- Godefroid Muzalia Kihangu, Bundu dia Kongo, une résurgence des messianismes et de l’alliance des Bakongo?, Universiteit Gent, België, 2011, p. 178

- Shillington, Kevin (2013). Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set. Routledge. pp. 773–775. ISBN 978-1-135-45670-2.

- Thompson, Estevam (2016). Timothy J. Stapleton (ed.). Encyclopedia of African Colonial Conflicts. ABC-CLIO. pp. 377–378. ISBN 978-1-59884-837-3.

- "Grappe à Kongos". RFO-FMC (in French). 2002. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- Miller, Joseph C. (1973), Requiem for the "Jaga" (Requiem pour les "Jaga"), Cahiers d'Études Africaines, Vol. 13, Cahier 49 (1973), pages 121-149

- Birmingham, David (2009). "The Date and Significance of the Imbangala Invasion of Angola". The Journal of African History. 6 (2): 143–152. doi:10.1017/S0021853700005569.

- Vansina, Jan (1966). "More on the Invasions of Kongo and Angola by the Jaga and the Lunda". Journal of African History. 7 (3): 421–429. doi:10.1017/s0021853700006502.

- Fromont, Cécile (2014). The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 6–8. ISBN 978-1-4696-1871-5.

- Vansina, Jan (2010). Being Colonized: The Kuba Experience in Rural Congo, 1880–1960. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-299-23643-4.

- Paige, Jeffrey M. (1978). Agrarian Revolution. Simon and Schuster. pp. 216–217. ISBN 978-0-02-923550-8.

- LaGamma, Alisa (2015). Kongo: Power and Majesty. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-1-58839-575-7.

- Thornton, John (1983), The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641–1718, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Thornton (1998). The Kongolese Saint Anthony. pp. 1–2, 214–215., Quote: "Dona Beatriz had sought to end the wars that fed this trade in humans...."

- Page (2003). Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia. pp. 778–780.

- LaGamma, Alisa (2015). Kongo: Power and Majesty. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-58839-575-7.

- Thornton, John (1998). The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684-1706. Cambridge University Press. pp. 113–117. ISBN 978-0-521-59649-7.

- Thornton (1998). The Kongolese Saint Anthony. pp. 1–3, 81–82, 162–163, 184–185.

- LaGamma, Alisa (2015). Kongo: Power and Majesty. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 104–108. ISBN 978-1-58839-575-7.

- Eltis, David, and David Richardson (2015), Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 2nd Edition, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0300212549; Archive: Slave Route Maps, see Map 9; The transatlantic slave trade volume over the 350+ years involved an estimated 12.5 million Africans, almost every country that bordered the Atlantic ocean, as well as Mozambique and the Swahili coast.

- Salas, Antonio; Richards, Martin; et al. (2004). "The African Diaspora: Mitochondrial DNA and the Atlantic Slave Trade". The American Journal of Human Genetics. Elsevier. 74 (3): 454–465. doi:10.1086/382194. PMC 1182259. PMID 14872407.

- Vansina (2010). Being Colonized. pp. 10–11.

- Laman, Karl, The Kongo (4 volumes, Stockholm, Uppsala, and Lund, 1953–1968).

- Gondola, Didier (2002). The History of Congo. Greenwood. pp. 50–58. ISBN 978-0-313-31696-8.

- Martin, Peggy J. (2005). SAT Subject Tests: World History 2005–2006. p. 316.

- Stearns, Peter N.; Langer, William Leonard (2001). The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged. p. 1065.

- Documentation for ISO 639 identifier: kon SIL, OLAC resources in and about the Kongo language Open Language Archives

- Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Bantoid, Southern, Narrow Bantu, Central, H, Kongo (H.10), Ethnologue.

- John Thornton, "Religious and Ceremonial Life in the Kongo and Mbundu Areas," in Linda M. Heywood (ed) Central Africans and Cultural Transformations in the American Disapora (London and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 978-0-521-00278-3, pp. 73–74.

- Thornton (2002), "Religious and Ceremonial Life", pp. 72–73.

- Thornton (2002), "Religious and Ceremonial Life," pp. 74–77.

- Thornton (2002), "Religious and Ceremonial Life," pp. 84–86.

- Thornton, John (1984). "The Development of an African Catholic Church in the Kingdom of Kongo, 1491–1750". Journal of African History. 25 (2): 147–167. doi:10.1017/s0021853700022830. JSTOR 181386.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt, Religion and Society in Central Africa: The Bakongo of Lower Zaire (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986).

- Hersak, Dunja (2001). "There Are Many Kongo Worlds: Particularities of Magico-Religious Beliefs among the Vili and Yombe People of Congo-Brazzaville". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 71 (2): 614–640. doi:10.3366/afr.2001.71.4.614. JSTOR 1161582.

- Janzen, John, Lemba, 1650–1930: a drum of affliction in Africa and the New World (New York, Garland, 1982).

- Hein Vanhee, "Central African Popular Christianity and the Development of Voudou Religion in Haiti," in Heywood, Central Africans, pp. 243–64.

- Morris, Brian (2006). Religion and Anthropology: A Critical Introduction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 153–155. ISBN 978-0-521-85241-8.

- Conrad, Joseph (2008). Heart of Darkness and the Congo Diary: A Penguin Enriched eBook Classic. Penguin. pp. 133 with note 27. ISBN 978-1-4406-5759-7.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt (2000). Kongo Political Culture: The Conceptual Challenge of the Particular. Indiana University Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-253-33698-8.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt, "The Eyes of Understanding: Kongo Minkisi," in Michael Harris, ed. Astonishment and Power (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993), pp. 22–23.

- Martin, Phyllis (1995). Leisure and Society in Colonial Brazzaville. Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–125.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kongo people. |

- Balandier, Georges (1968). Daily Life in the Kingdom of the Kongo: 16th to 19th centuries. New York: Random House.

- Batsîkama Ba Mampuya Ma Ndâwala, Raphaël (1966/1998). Voici les Jaga. Paris: L'Harmattan.

- Bockie, Simon (1993). Death and the Invisible Powers: The World of Kongo Belief Bloomington: Indiana University Press

- Eckholm-Friedman, Kajsa (1991). Catastrophe and Creation: The Transformation of an African Culture Reading and Amsterdam: Harwood

- Fu-kiau kia Bunseki (1969). Le mukongo et le monde que l'entourait/N'kongo ye nza yakundidila Kinshasa: Office national de le recherche et de le devéloppement.

- Hilton, Anne (1982). The Kingdom of Kongo. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heusch, Luc de (2000). Le roi de Kongo et les monstres sacrės. Paris: Gallimard.

- Janzen, John (1982). Lemba, 1650–1932: A Drum of Affliction in Africa and the New World. New York: Garland.

- Laman, Karl (1953–1968). The Kongo Uppsala: Alqvist and Wilsells.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt (1970). Custom and Government in the Lower Congo. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt (1977). "Fetishism Revisited: Kongo nkisi in sociological perspective," Africa 47/2, pp. 140–52.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt (1983). Modern Kongo Prophets: Religion in a Plural Society. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt (1986). Religion and Society in Central Africa: The BaKongo of Lower Zaire. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt (1991), ed. and trans. Art and Healing of the Bakongo commented upon by themselves: Minkisi from the Laman Collection. Bloomington: Indiana University Press and Stockholm: Folkens-museum etnografiska.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt (1994). "The Eye of Understanding: Kongo minkisi" in Astonishment and Power Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. 21–103.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt (2000). Kongo Political Culture: The Conceptual Challenge of the Particular Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Nsondė, Jean de Dieu (1995). Langues, histoire, et culture Koongo aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles Paris: L'Harmattan.

- Randles, William G. L. (1968). L'ancien royaume du Congo des origines à la fin du XIX e siècle. Paris: Mouton

- Thompson, Robert Farris (1983). Flash of the Spirit New York: Random House.

- Thompson, Robert Farris and Jean Cornet (1981). Four Moments of the Sun. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press

- Thornton, John (1983). The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641–1718. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Thornton, John (1998). The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706 (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Volavka, Zdenka (1998). Crown and Ritual: The Royal Insignia of Ngoyo ed. Wendy A Thomas. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.