Zoophilia

Zoophilia is a paraphilia involving a sexual fixation on non-human animals. Bestiality is cross-species sexual activity between humans and non-human animals. The terms are often used interchangeably, but some researchers make a distinction between the attraction (zoophilia) and the act (bestiality).[1]

Although sex with animals is not outlawed in some countries, in most countries, bestiality is illegal under animal abuse laws or laws dealing with buggery or crimes against nature.

Terminology

General

Three key terms commonly used in regards to the subject—zoophilia, bestiality, and zoosexuality—are often used somewhat interchangeably. Some researchers distinguish between zoophilia (as a persistent sexual interest in animals) and bestiality (as sexual acts with animals), because bestiality is often not driven by a sexual preference for animals.[1] Some studies have found a preference for animals is rare among people who engage in sexual contact with animals.[2] Furthermore, some zoophiles report they have never had sexual contact with an animal.[3] People with zoophilia are known as "zoophiles", though also sometimes as "zoosexuals", or even very simply "zoos".[1][4] Zooerasty, sodomy, and zooerastia[5] are other terms closely related to the subject but are less synonymous with the former terms, and are seldom used. "Bestiosexuality" was discussed briefly by Allen (1979), but never became widely established. Ernest Bornemann (1990, cited by Rosenbauer, 1997) coined the separate term zoosadism for those who derive pleasure – sexual or otherwise – from inflicting pain on animals. Zoosadism specifically is one member of the Macdonald triad of precursors to sociopathic behavior.[6]

Zoophilia

The term zoophilia was introduced into the field of research on sexuality in Psychopathia Sexualis (1886) by Krafft-Ebing, who described a number of cases of "violation of animals (bestiality)",[7] as well as "zoophilia erotica",[8] which he defined as a sexual attraction to animal skin or fur. The term zoophilia derives from the combination of two nouns in Greek: ζῷον (zṓion, meaning "animal") and φιλία (philia, meaning "(fraternal) love"). In general contemporary usage, the term zoophilia may refer to sexual activity between human and non-human animals, the desire to engage in such, or to the specific paraphilia (i.e., the atypical arousal) which indicates a definite preference for non-human animals over humans as sexual partners. Although Krafft-Ebing also coined the term zooerasty for the paraphilia of exclusive sexual attraction to animals,[9] that term has fallen out of general use.

Zoosexuality

The term zoosexual was proposed by Hani Miletski in 2002[4] as a value-neutral term. Usage of zoosexual as a noun (in reference to a person) is synonymous with zoophile, while the adjectival form of the word – as, for instance, in the phrase "zoosexual act" – may indicate sexual activity between a human and a non-human animal. The derivative noun "zoosexuality" is sometimes used by self-identified zoophiles in both support groups and on internet-based discussion forums to designate sexual orientation manifesting as romantic or emotional involvement with, or sexual attraction to, non-human animals.[4][10]

Bestiality

The legal term bestiality has three common pronunciations: [ˌbestʃiˈæləti] or [ˌbistʃiˈæləti] in the United States,[11] and [ˌbestiˈæləti] in the United Kingdom.[12] Some zoophiles and researchers draw a distinction between zoophilia and bestiality, using the former to describe the desire to form sexual relationships with animals, and the latter to describe the sex acts alone.[13] Confusing the matter yet further, writing in 1962, Masters used the term bestialist specifically in his discussion of zoosadism.

Stephanie LaFarge, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the New Jersey Medical School, and Director of Counseling at the ASPCA, writes that two groups can be distinguished: bestialists, who rape or abuse animals, and zoophiles, who form an emotional and sexual attachment to animals.[14] Colin J. Williams and Martin Weinberg studied self-defined zoophiles via the internet and reported them as understanding the term zoophilia to involve concern for the animal's welfare, pleasure, and consent, as distinct from the self-labelled zoophiles' concept of "bestialists", whom the zoophiles in their study defined as focused on their own gratification. Williams and Weinberg also quoted a British newspaper saying that zoophilia is a term used by "apologists" for bestiality.[15]

Extent of occurrence

The Kinsey reports rated the percentage of people who had sexual interaction with animals at some point in their lives as 8% for men and 3.6% for women, and claimed it was 40–50% in people living near farms,[9] but some later writers dispute the figures, because the study lacked a random sample in that it included a disproportionate number of prisoners, causing sampling bias. Martin Duberman has written that it is difficult to get a random sample in sexual research, and that even when Paul Gebhard, Kinsey's research successor, removed prison samples from the figures, he found the figures were not significantly changed.[16]

By 1974, the farm population in the USA had declined by 80 percent compared with 1940, reducing the opportunity to live with animals; Hunt's 1974 study suggests that these demographic changes led to a significant change in reported occurrences of bestiality. The percentage of males who reported sexual interactions with animals in 1974 was 4.9% (1948: 8.3%), and in females in 1974 was 1.9% (1953: 3.6%). Miletski believes this is not due to a reduction in interest but merely a reduction in opportunity.[17]

Nancy Friday's 1973 book on female sexuality, My Secret Garden, comprised around 190 fantasies from different women; of these, 23 involve zoophilic activity.[18]

In one study, psychiatric patients were found to have a statistically significant higher prevalence rate (55 percent) of reported bestiality, both actual sexual contacts (45 percent) and sexual fantasy (30 percent) than the control groups of medical in-patients (10 percent) and psychiatric staff (15 percent).[19] Crépault and Couture (1980) reported that 5.3 percent of the men they surveyed had fantasized about sexual activity with an animal during heterosexual intercourse.[20] In a 2014 study, 3% of women and 2.2% of men reported fantasies about having sex with an animal.[21] A 1982 study suggested that 7.5 percent of 186 university students had interacted sexually with an animal.[22]

Sexual arousal from watching animals mate is known as faunoiphilia.[23] A frequent interest in and sexual excitement at watching animals mate is cited as an indicator of latent zoophilia by Massen (1994).

Perspectives on zoophilia

Research perspectives

Zoophilia has been partly discussed by several sciences: psychology (the study of the human mind), sexology (a relatively new discipline primarily studying human sexuality), ethology (the study of animal behavior), and anthrozoology (the study of human–animal interactions and bonds).

In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), zoophilia is placed in the classification "other specified paraphilic disorder"[24] ("paraphilias not otherwise specified" in the DSM-III and IV[25][26][27][28]). The World Health Organization takes the same position, listing a sexual preference for animals in its ICD -10 as "other disorder of sexual preference".[29] In the DSM-5, it rises to the level of a diagnosable disorder only when accompanied by distress or interference with normal functioning.[24][30]

Zoophilia may also be covered to some degree by other fields such as ethics, philosophy, law, animal rights and animal welfare. It may also be touched upon by sociology which looks both at zoosadism in examining patterns and issues related to sexual abuse and at non-sexual zoophilia in examining the role of animals as emotional support and companionship in human lives, and may fall within the scope of psychiatry if it becomes necessary to consider its significance in a clinical context. The Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine (Vol. 18, February 2011) states that sexual contact with animals is almost never a clinically significant problem by itself;[31] it also states that there are several kinds of zoophiles:[31]

- Human-animal role-players

- Romantic zoophiles

- Zoophilic fantasizers

- Tactile zoophiles

- Fetishistic zoophiles

- Sadistic bestials

- Opportunistic zoophiles

- Regular zoophiles

- Exclusive zoophiles

Additionally, zoophiles in categories 2, 3, and 8 (romantic zoophiles, zoophilic fantasizers, and regular zoophiles) are the most common, while zoophiles found in categories 6 and 7 (sadistic bestials and opportunistic zoophiles) are the least common.[31]

Zoophilia may reflect childhood experimentation, sexual abuse or lack of other avenues of sexual expression. Exclusive desire for animals rather than humans is considered a rare paraphilia, and sufferers often have other paraphilias[32] with which they present. Zoophiles will not usually seek help for their condition, and so do not come to the attention of psychiatrists for zoophilia itself.[33]

The first detailed studies of zoophilia date from prior to 1910. Peer reviewed research into zoophilia in its own right started around 1960. However, a number of the most oft-quoted studies, such as Miletski, were not published in peer-reviewed journals. There have been several significant modern books, from Masters (1962) to Beetz (2002);[34] their research arrived at the following conclusions:

- Most zoophiles have (or have also had) long term human relationships as well or at the same time as zoosexual ones, and that zoosexual partners are usually dogs and/or horses (Masters, Miletski, Beetz)[34][35]

- Zoophiles' emotions and care for animals can be real, relational, authentic and (within animals' abilities) reciprocal, and not just a substitute or means of expression.[36] Beetz believes zoophilia is not an inclination which is chosen.[34]

- Society in general at present is considerably misinformed about zoophilia, its stereotypes, and its meaning.[34] The distinction between zoophilia and zoosadism is a critical one to these researchers, and is highlighted by each of these studies. Masters (1962), Miletski (1999) and Weinberg (2003) each comment significantly on the social harm caused by misunderstandings regarding zoophilia: "This destroy[s] the lives of many citizens".[34]

Beetz also states the following:

The phenomenon of sexual contact with animals is starting to lose its taboo: it is appearing more often in scholarly publications, and the public are being confronted with it, too. ... Sexual contact with animals – in the form of bestiality or zoophilia – needs to be discussed more openly and investigated in more detail by scholars working in disciplines such as animal ethics, animal behavior, anthrozoology, psychology, mental health, sociology, and the law.[37]

More recently, research has engaged three further directions: the speculation that at least some animals seem to enjoy a zoophilic relationship assuming sadism is not present, and can form an affectionate bond.[38] Similar findings are also reported by Kinsey (cited by Masters), and others earlier in history. Miletski (1999) notes that information on sex with animals on the internet is often very emphatic as to what the zoophile believes gives pleasure and how to identify what is perceived as consent beforehand. For instance, Jonathan Balcombe says animals do things for pleasure. But he himself says pet owners will be unimpressed by this statement, as this is not news to them.[39]

Beetz described the phenomenon of zoophilia/bestiality as being somewhere between crime, paraphilia and love, although she says that most research has been based on criminological reports, so the cases have frequently involved violence and psychiatric illness. She says only a few recent studies have taken data from volunteers in the community.[40] As with all volunteer surveys and sexual ones in particular, these studies have a potential for self-selection bias.[41]

Medical research suggests that some zoophiles only become aroused by a specific species (such as horses), some zoophiles become aroused by multiple species (which may or may not include humans), and some zoophiles are not attracted to humans at all.[2][42]

Researchers who observed a monkey trying to mate with a deer in 2017 (interspecies sex) said that it may provide clues into why humans have interspecies sex.[43][44][45]

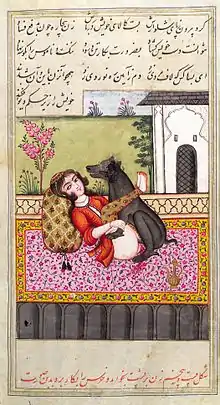

Historical and cultural perspectives

Instances of this behavior have been found in the Bible.[46] In a cave painting from at least 8000 BC in the Northern Italian Val Camonica a man is shown about to penetrate an animal. Raymond Christinger interprets that as a show of power of a tribal chief,[47] and so we do not know if this practice was then more acceptable, and if the scene depicted was usual or unusual or whether it was symbolic or imaginary.[48] The "Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art" says the scene may be humorous, as the penetrating man seems to be waving cheerfully with his hand at the same time. Potters seem to have spent time depicting the practice, but this may be because they found the idea amusing.[49] Dr "Jacobus X", said to be the pen name of a French author, said this was clearly "before any known taboos against sex with animals existed".[50] Marc Epprecht states that authors such as Jacobus X do not deserve respect because their methodology is based on hearsay, and was designed for voyeuristic titillation of the reader.[51] Masters said that since pre-historic man is prehistoric it goes without saying that we know little of his sexual behaviour;[52] depictions in cave paintings may only show the artist's subjective preoccupations or thoughts.

Pindar, Herodotus, and Plutarch claimed the Egyptians engaged in ritual congress with goats.[53] Such claims about other cultures do not necessarily reflect anything about which the author had evidence, but may be a form of propaganda or xenophobia, similar to blood libel.

Bestiality was accepted in some North American and Middle Eastern indigenous cultures.[54] Sexual intercourse between humans and non-human animals was not uncommon among certain Native American indigenous peoples, including the Hopi.[55][56] Voget describes the sexual lives of young Native Americans as "rather inclusive", including bestiality.[55] In addition, the Copper Inuit people had "no aversion to intercourse with live animals".[55]

Several cultures built temples (Khajuraho, India) or other structures (Sagaholm, barrow, Sweden) with zoophilic carvings on the exterior, however at Khajuraho, these depictions are not on the interior, perhaps depicting that these are things that belong to the profane world rather than the spiritual world, and thus are to be left outside.

In the Church-oriented culture of the Middle Ages, zoophilic activity was met with execution, typically burning, and death to the animals involved either the same way or by hanging, as "both a violation of Biblical edicts and a degradation of man as a spiritual being rather than one that is purely animal and carnal".[57] Some witches were accused of having congress with the devil in the form of an animal. As with all accusations and confessions extracted under torture in the witch trials in Early Modern Europe, their validity cannot be ascertained.[53]

Religious perspectives

Passages in Leviticus 18 (Lev 18:23: "And you shall not lie with any beast and defile yourself with it, neither shall any woman give herself to a beast to lie with it: it is a perversion." RSV) and 20:15–16 ("If a man lies with a beast, he shall be put to death; and you shall kill the beast. If a woman approaches any beast and lies with it, you shall kill the woman and the beast; they shall be put to death, their blood is upon them." RSV) are cited by Jewish, Christian, and Muslim theologians as categorical denunciation of bestiality. However, the teachings of the New Testament have been interpreted by some as not expressly forbidding bestiality.[58]

In Part II of his Summa Theologica, medieval philosopher Thomas Aquinas ranked various "unnatural vices" (sex acts resulting in "venereal pleasure" rather than procreation) by degrees of sinfulness, concluding that "the most grievous is the sin of bestiality".[59] Some Christian theologians extend Matthew's view that even having thoughts of adultery is sinful to imply that thoughts of committing bestial acts are likewise sinful.

There are a few references in Hindu scriptures to religious figures engaging in symbolic sexual activity with animals such as explicit depictions of people having sex with animals included amongst the thousands of sculptures of "Life events" on the exterior of the temple complex at Khajuraho. The depictions are largely symbolic depictions of the sexualization of some animals and are not meant to be taken literally.[60] According to the Hindu tradition of erotic painting and sculpture, having sex with an animal is believed to be actually a human having sex with a god incarnated in the form of an animal.[61] However, in some Hindu scriptures, such as the Bhagavata Purana and the Devi Bhagavata Purana, having sex with animals, especially the cow, leads one to hell, where one is tormented by having one's body rubbed on trees with razor-sharp thorns.[62]

Legal status

In many jurisdictions, all forms of zoophilic acts are prohibited; others outlaw only the mistreatment of animals, without specific mention of sexual activity. In the United Kingdom, Section 63 of the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008 (also known as the Extreme Pornography Act) outlaws images of a person performing or appearing to perform an act of intercourse or oral sex with an animal (whether dead or alive).[63] Despite the UK Ministry of Justice's explanatory note on extreme images saying "It is not a question of the intentions of those who produced the image. Nor is it a question of the sexual arousal of the defendant",[64] "it could be argued that a person might possess such an image for the purposes of satire, political commentary or simple grossness," according to The Independent.[65]

Many new laws banning sex with animals have been made recently, such as in New Hampshire,[66] Ohio, Germany,[67] Sweden,[68] Denmark,[69]Thailand,[70] Costa Rica,[71] Bolivia,[72] and Guatemala.[73] The number of jurisdictions around the world banning it has grown in the 2000s and 2010s.

The only EU countries where zoophilia remains legal are Finland, Hungary, and Romania.[74] It is also legal in Malta but not desired to remain so.[75]

Laws on zoophilia are sometimes triggered by specific incidents.[76] While some laws are very specific, others employ vague terms such as "sodomy" or "bestiality", which lack legal precision and leave it unclear exactly which acts are covered. In the past, some bestiality laws may have been made in the belief that sex with an animal could result in monstrous offspring, as well as offending the community. Current anti-cruelty laws focus more specifically on animal welfare while anti-bestiality laws are aimed only at offenses to community "standards".[77] Notable legal views include Sweden, where a 2005 report by the Swedish Animal Welfare Agency for the government expressed concern over the increase in reports of horse-ripping incidents. The agency believed current animal cruelty legislation was not sufficient in protecting animals from abuse and needed updating, but concluded that on balance it was not appropriate to call for a ban.[78] In New Zealand, the 1989 Crimes Bill considered abolishing bestiality as a criminal offense, and instead viewing it as a mental health issue, but they did not, and people can still be prosecuted for it. Under Section 143 of the Crimes Act 1961, individuals can serve a sentence of seven years duration for animal sexual abuse and the offence is considered 'complete' in the event of 'penetration'.[79] In Canada, a clarification of the anti-bestiality law was made in 2016 which legalizes most forms of sexual contact with animals other than penetration.[80]

Some countries once had laws against single males living with female animals, such as alpacas. Copulating with a female alpaca is still specifically against the law in Peru.[81]

As of 2017, bestiality is illegal in 45 U.S. states. Most state bestiality laws were enacted between 1999 and 2017.[82][83] Until 2005, there was a farm near Enumclaw, Washington that was described as an "animal brothel", where people paid to have sex with animals. After an incident on 2 July 2005, when a man was pronounced dead in the emergency room of the Enumclaw community hospital after his colon ruptured due to having had anal sex with a horse, the farm garnered police attention. The state legislature of the State of Washington, which had been one of the few states in the United States without a law against bestiality, within six months passed a bill making bestiality illegal.[84][85] Arizona,[86] Alaska,[87] Florida,[88] Alabama,[89] New Jersey,[90] New Hampshire,[66] Ohio,[91] Texas,[92] Vermont,[93] and Nevada[94] have banned sex with animals between 2006 and the present, with the latter 5 all banning it in 2017. When such laws are proposed, they are never questioned or debated.[95][96] Laws which prohibit non-abusive bestiality have been criticized for being discriminatory, unjust and unconstitutional.[97][98]

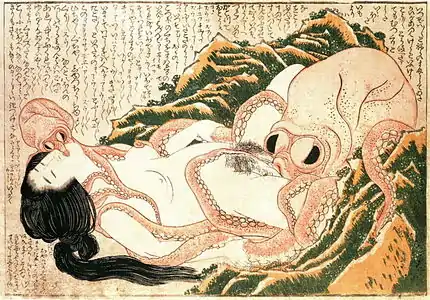

Pornography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zoophilia in art. |

.jpg.webp)

Pornography involving sex with animals is widely illegal, even in most countries where bestiality itself is not explicitly outlawed.

In the United States, zoophilic pornography would be considered obscene if it did not meet the standards of the Miller Test and therefore is not openly sold, mailed, distributed or imported across state boundaries or within states which prohibit it. Under U.S. law, 'distribution' includes transmission across the Internet. Production and mere possession appears to be legal, however. U.S. prohibitions on distribution of sexual or obscene materials are as of 2005 in some doubt, having been ruled unconstitutional in United States v. Extreme Associates (a judgement which was overturned on appeal, December 2005).

Similar restrictions apply in Germany (see above). In New Zealand the possession, making or distribution of material promoting bestiality is illegal.

The potential use of media for pornographic movies was seen from the start of the era of silent film. Polissons and Galipettes (re-released 2002 as "The Good Old Naughty Days") is a collection of early French silent films for brothel use, including some animal pornography, dating from around 1905 – 1930.

Material featuring sex with animals is widely available on the Internet, due to its ease of production. Prior to the advent of mass-market magazines such as Playboy, so-called Tijuana Bibles were a form of pornographic tract popular in America, sold as anonymous underground publications typically comprising a small number of stapled comic-strips representing characters and celebrities.[99] The promotion of "stars" began with the Danish Bodil Joensen, in the period of 1969–72, along with other porn actors such as the Americans Linda Lovelace (Dogarama, 1969), Chessie Moore (multiple films, c. 1994), Kerri Downs (three films, 1998) and Calina Lynx (aka Kelly G'raffe) (two films, 1998). Another early film to attain great infamy was "Animal Farm", smuggled into Great Britain around 1980 without details as to makers or provenance.[100] The film was later traced to a crude juxtaposition of smuggled cuts from many of Bodil Joensen's 1970s Danish movies.

Into the 1980s, the Dutch took the lead, creating figures like "Wilma" and the "Dutch Sisters". In the 1980s, "bestiality" was featured in Italian adult films with actresses like Denise Dior, Francesca Ray, and Marina Hedman, manifested early in the softcore flick Bestialità in 1976.

Today, in Hungary, where production faces no legal limitations, zoophilic materials have become a substantial industry that produces a number of films and magazines, particularly for Dutch companies such as Topscore and Book & Film International, and the genre has stars such as "Hector", a great dane dog starring in several films. Many Hungarian mainstream performers also appeared anonymously in animal pornography in their early careers, including for example, Suzy Spark.[101]

In Japan, animal pornography is used to bypass censorship laws, often featuring Japanese and Swedish female models performing fellatio on animals, because oral penetration of a non-human penis is not in the scope of Japanese mosaic censor. Sakura Sakurada is an AV idol known to have appeared in animal pornography, specifically in the AV The Dog Game in 2006. While primarily underground, there are a number of animal pornography actresses who specialize in bestiality movies. A box-office success of the 1980s, 24 Horas de Sexo Explícito featured zoophilia.

In the United Kingdom, Section 63 of the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008 criminalises possession of realistic pornographic images depicting sex with animals (see extreme pornography), including fake images and simulated acts, as well as images depicting sex with dead animals, where no crime has taken place in the production. The law provides for sentences of up to two years in prison; a sentence of 12 months was handed down in one case in 2011.[102]

Pornography of this sort has become the business of certain spammers such as Jeremy Jaynes and owners of some fake TGPs, who use the promise of "extreme" material as a bid for users' attention.

Health and safety

Infections that are transmitted from animals to humans are called zoonoses. Some zoonoses may be transferred through casual contact, but others are much more readily transferred by activities that expose humans to the semen, vaginal fluids, urine, saliva, feces and blood of animals. Examples of zoonoses are Brucellosis, Q fever, leptospirosis, and toxocariasis. Therefore, sexual activity with animals is, in some instances, a high risk activity. Allergic reactions to animal semen may occur, including anaphylaxis. Bites and other trauma from penetration or trampling may occur.

Zoophiles

Non-sexual zoophilia

The love of animals is not necessarily sexual in nature. In psychology and sociology the word "zoophilia" is sometimes used without sexual implications. Being fond of animals in general, or as pets, is accepted in Western society, and is usually respected or tolerated. However, the word zoophilia is used to mean a sexual preference towards animals, which makes it[103] a paraphilia. Some zoophiles may not act on their sexual attraction to animals. People who identify as zoophiles may feel their love for animals is romantic rather than purely sexual, and say this makes them different from those committing entirely sexually motivated acts of bestiality.[104]

Zoophile community

An online survey which recruited participants over the internet concluded that prior to the arrival of widespread computer networking, most zoophiles would not have known other zoophiles, and for the most part, zoophiles engaged in bestiality secretly, or told only trusted friends, family or partners. The internet and its predecessors made people able to search for information on topics which were not otherwise easily accessible and to communicate with relative safety and anonymity. Because of the diary-like intimacy of blogs and the anonymity of the internet, zoophiles had the ideal opportunity to "openly" express their sexuality.[105] As with many other alternate lifestyles, broader networks began forming in the 1980s when participating in networked social groups became more common at home and elsewhere.[106] Such developments in general were described by Markoff in 1990; the linking of computers meant that people thousands of miles apart could feel the intimacy akin to being in a small village together.[107] The popular newsgroup alt.sex.bestiality, said to be in the top 1% of newsgroup interest (i.e. number 50 out of around 5000), – and reputedly started in humor[108] – along with personal bulletin boards and talkers, chief among them Sleepy's multiple worlds, Lintilla, and Planes of Existence, were among the first group media of this kind in the late 1980s and early 1990s. These groups rapidly drew together zoophiles, some of whom also created personal and social websites and internet forums. By around 1992–1994, the wide social net had evolved.[109] This was initially centered around the above-mentioned newsgroup, alt.sex.bestiality, which during the six years following 1990 had matured into a discussion and support group.[110][111][112][113] The newsgroup included information about health issues, laws governing zoophilia, bibliography relating to the subject, and community events.[114]

Weinberg and Williams observe that the internet can socially integrate an incredibly large number of people. In Kinsey's day contacts between animal lovers were more localized and limited to male compatriots in a particular rural community. Further, while the farm boys Kinsey researched might have been part of a rural culture in which sex with animals was a part, the sex itself did not define the community. The zoophile community is not known to be particularly large compared to other subcultures which make use of the internet, so Weinberg and Williams surmised its aims and beliefs would likely change little as it grew. Those particularly active on the internet may not be aware of a wider subculture, as there is not much of a wider subculture, Weinberg and Williams felt the virtual zoophile group would lead the development of the subculture.[106]

Websites aim to provide support and social assistance to zoophiles (including resources to help and rescue abused or mistreated animals), but these are not usually well publicized. Such work is often undertaken as needed by individuals and friends, within social networks, and by word of mouth.[115]

Zoophiles tend to experience their first zoosexual feelings during adolescence, and tend to be secretive about it, hence limiting the ability for non-Internet communities to form.[116]

Debate over zoophilia or zoophilic relations

Because of its controversial nature, people have developed arguments both for[117] and against[118] zoophilia. Arguments for and against zoosexual activity from a variety of sources, including religious, moral, ethical, psychological, medical and social.

Arguments against bestiality

Bestiality is seen by the government of the United Kingdom as profoundly disturbed behavior (as indicated by the UK Home Office review on sexual offences in 2002).[119] Andrea Beetz states there is evidence that there can be violent zoosadistic approaches to sex with animals. Beetz argues that animals might be traumatized even by a non-violent, sexual approach from a human;[120] however, Beetz also says that in some cases, non-abusive bestiality can be reciprocally pleasurable for both the human and non-human animal.[120]

An argument from human dignity is given by Wesley J. Smith, a senior fellow and Intelligent Design proponent at the Center for Science and Culture of the conservative Christian Discovery Institute: – "such behavior is profoundly degrading and utterly subversive to the crucial understanding that human beings are unique, special, and of the highest moral worth in the known universe—a concept known as 'human exceptionalism' ... one of the reasons bestiality is condemned through law is that such degrading conduct unacceptably subverts standards of basic human dignity and is an affront to humankind's inestimable importance and intrinsic moral worth."[121]

One of the primary critiques of bestiality is that it is harmful to animals and necessarily abusive, because animals are unable to give or withhold consent.[122]

The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) has said that as animals do not have the same capacity for thinking as humans, they are unable to give full consent. The HSUS takes the position that all sexual activity between humans and animals is abusive, whether it involves physical injury or not.[123] In his 1993 article, Dr. Frank Ascione stated that "bestiality may be considered abusive even in cases when physical harm to an animal does not occur." In a 1997 article, Piers Beirne, Professor of Criminology at the University of Southern Maine, points out that 'for genuine consent to sexual relations to be present...both participants must be conscious, fully informed and positive in their desires.'[124][125]

Arguments for bestiality

Some defenders of bestiality argue that the issue of sexual consent is irrelevant because many legal human practices (such as semen collection, artificial insemination, hunting, laboratory testing, and slaughtering animals for meat) do not involve the consent of the animal.[126] Brian Cutteridge states the following regarding this argument:

"Animal sexual autonomy is regularly violated for human financial gain through procedures such as [artificial insemination and slaughter]. Such procedures are probably more disturbing physically and psychologically than acts of zoophilia would be, yet the issue of consent on the part of the animal is never raised in the discussion of such procedures. To confine the 'right' of any animal strictly to acts of zoophilia is thus to make a law [against zoophilia] based not on reason but on moral prejudice, and to breach the constitutional rights of zoophiles to due process and equality before the law. [...] Laws which criminalize zoophilia based on societal abhorrence of such acts rather than any real harm caused by such acts are an unjust and unconstitutional infringement on individual liberty."[97]

Hani Miletski believes that "Animals are capable of sexual consent – and even initiation – in their own way."[127] It is not an uncommon practice for dogs to attempt to copulate with ("hump") the legs of people of both genders.[128] Rosenberger (1968) emphasizes that as far as cunnilingus is concerned, dogs require no training, and even Dekkers (1994) and Menninger (1951) admit that sometimes animals take the initiative and do so impulsively.[120] Those supporting zoophilic activity feel animals sometimes even seem to enjoy the sexual attention[129] or voluntarily initiate sexual activity with humans.[130] Animals such as dogs can be willing participants in sexual activity with humans, and "seem to enjoy the attention provided by the sexual interaction with a human."[97] Animal owners normally know what their own pets like or do not like. Most people can tell if an animal does not like how it is being petted, because it will move away. An animal that is liking being petted pushes against the hand, and seems to enjoy it. To those defending bestiality this is seen as a way in which animals give consent, or the fact that a dog might wag its tail.[131]

Utilitarian philosopher and animal liberation author Peter Singer argues that bestiality is not unethical so long as it involves no harm or cruelty to the animal[132] (see Harm principle). In the article "Heavy Petting,"[133] Singer argues that zoosexual activity need not be abusive, and that relationships could form which were mutually enjoyed. Singer and others have argued that people's dislike of bestiality is partly caused by irrational speciesism and anthropocentrism.[134][135] Because interspecies sex occurs in nature,[136] and because humans are animals,[137] supporters argue that zoosexual activity is not "unnatural" and is not intrinsically wrong.[98][138]

Research has proven that non-human animals can and do have sex for non-reproductive purposes (and for pleasure).[139] In 2006, a Danish Animal Ethics Council report concluded that ethically performed zoosexual activity is capable of providing a positive experience for all participants, and that some non-human animals are sexually attracted to humans[140] (for example, dolphins).[141]

Some zoophiles claim that they are not abusive towards animals:[96]

"In other recent surveys, the majority of zoophiles scoffed at the notion that they were abusive toward animals in any way—far from it, they said. Many even consider themselves to be animal welfare advocates in addition to zoophiles."[96]

Mentions in the media

Because of its controversial nature, different countries vary in the discussion of bestiality. Often sexual matters are the subject of legal or regulatory requirement. In 2005 the UK broadcasting regulator (OFCOM) updated its code stating that freedom of expression is at the heart of any democratic state. Adult audiences should be informed as to what they will be viewing or hearing, and the young, who cannot make a fully informed choice for themselves, should be protected. Hence a watershed and other precautions were set up for explicit sexual material, to protect young people. Zoophile activity and other sexual matters may be discussed, but only in an appropriate context and manner.[142]

After the Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act in 1993, the IPT was replaced with bodies designed to allow both more debate and increased consistency, and possession and supply of material that it is decided are objectionable was made a criminal offence.

See also

|

|

References and footnotes

- Ranger, R.; Fedoroff, P. (2014). "Commentary: Zoophilia and the Law". Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online. 42 (4): 421–426. PMID 25492067.

- Earls, C. M.; Lalumiere, M. L. (2002). "A Case Study of Preferential Bestiality (Zoophilia)". Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 14 (1): 83–88. doi:10.1177/107906320201400106. PMID 11803597. S2CID 43450855.

- Maratea, R. J. (2011). "Screwing the pooch: Legitimizing accounts in a zoophilia on-line community". Deviant Behavior. 32 (10): 938. doi:10.1080/01639625.2010.538356. S2CID 145637418.

- Beetz, Andrea M. (2010). "Bestiality and Zoophilia: A Discussion of Sexual Contact With Animals". In Ascione, Frank (ed.). The International Handbook of Animal Abuse and Cruelty: Theory, Research, and Application. ISBN 978-1-55753-565-8.

- "zooerastia definition". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- MacDonald, J. M. (1963). "The Threat to Kill". American Journal of Psychiatry. 120 (2): 125–30. doi:10.1176/ajp.120.2.125. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- Richard von Krafft-Ebing: Psychopathia Sexualis, p. 561.

- Richard von Krafft-Ebing: Psychopathia Sexualis, p. 281.

- D. Richard Laws and William T. O'Donohue: Books.Google.co.uk, Sexual Deviance, page 391. Guilford Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-59385-605-2.

- "What is zoosexuality". Zoosexuality.org. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- "Pronunciation of bestiality". MacMillan Dictionary. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- "Pronunciation of bestiality". MacMillan Dictionary. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- "Sexuality.about.com". Sexuality.about.com. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Melinda Roth (15 December 1991). "All Opposed, Say Neigh". Riverfront Times. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- Williams CJ, Weinberg MS (December 2003). "Zoophilia in men: a study of sexual interest in animals". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 32 (6): 523–35. doi:10.1023/A:1026085410617. PMID 14574096. S2CID 13386430.

- Richard Duberman: KinseyInstitute.org Archived 11 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Kinsey's Urethra The Nation, 3 November 1997, pp. 40–43. Review of Alfred C. Kinsey: A Public/Private Life. By James H. Jones.

- Hunt 1974, cited and re-examined by Miletski (1999)

- Nancy Friday (1998) [1973]. "What do women fantasize about? The Zoo". My Secret Garden (Revised ed.). Simon and Schuster. pp. 180–185. ISBN 978-0-671-01987-7.

- Alvarez, WA; Freinhar, JP (1991). "A prevalence study of bestiality (zoophilia) in psychiatric in-patients, medical in-patients, and psychiatric staff". International Journal of Psychosomatics. 38 (1–4): 45–7. PMID 1778686.

- Crépault, Claude; Couture, Marcel (1980). "Men's erotic fantasies". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 9 (6): 565–81. doi:10.1007/BF01542159. PMID 7458662. S2CID 9021936.

- Joyal, C. C.; Cossette, A.; Lapierre, V. (2014). "What Exactly Is an Unusual Sexual Fantasy?". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 12 (2): 328–340. doi:10.1111/jsm.12734. PMID 25359122.

- Story, MD (1982). "A comparison of university student experience with various sexual outlets in 1974 and 1980". Adolescence. 17 (68): 737–47. PMID 7164870.

- Aggrawal, Anil. Forensic and medico-legal aspects of sexual crimes and unusual sexual practices. CRC Press, 2008.

- American Psychiatric Association, ed. (2013). "Other Specified Paraphilic Disorder, 302.89 (F65.89)". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 705.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2000. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6. OCLC 43483668.

- Milner, J. S.; Dopke, C. A. (2008). "Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified: Psychopathology and theory". In Laws, D. R.; O'Donohue, W. T. (eds.). Sexual Deviance, Second Edition: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment. New York: The Guilford Press. pp. 384–418. ISBN 978-1-59385-605-2. OCLC 152580827.

- Money, John (1988). Lovemaps: Clinical Concepts of Sexual/Erotic Health and Pathology, Paraphilia, and Gender Transposition in Childhood, Adolescence, and Maturity. Buffalo, N.Y: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-0-87975-456-3. OCLC 19340917.

- Seto, MC; Barbaree HE (2000). "Paraphilias". In Hersen, M.; Van Hasselt, V. B. (eds.). Aggression and violence: an introductory text. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. pp. 198–213. ISBN 978-0-205-26721-7. OCLC 41380492.

- "International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10, F65.8 Other disorders of sexual preference". Who.int. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Miletski, H. (2015). "Zoophilia – Implications for Therapy". Journal of Sex Education and Therapy. 26 (2): 85–86. doi:10.1080/01614576.2001.11074387. S2CID 146150162.

- Aggrawal, Anil (2011). "A new classification of zoophilia". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 18 (2): 73–8. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2011.01.004. PMID 21315301.

- D. Richard Laws; William T. O'Donohue (January 2008). Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment. Guilford Press. p. 391. ISBN 978-1-59385-605-2.

- Richard W. Roukema (13 August 2008). What Every Patient, Family, Friend, and Caregiver Needs to Know About Psychiatry, Second Edition. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-58562-750-9.

- Beetz 2002, section 5.2.4 – 5.2.7.

- Anil Aggrawal (22 December 2008). Forensic and Medico-legal Aspects of Sexual Crimes and Unusual Sexual Practices. CRC Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-4200-4309-9. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- (Masters, Miletski, Weinberg, Beetz)

- Anthony L. Podberscek; Andrea M. Beetz (1 September 2005). Bestiality and Zoophilia: Sexual Relations with Animals. Berg. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-85785-222-9. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Masters, 1962.

- Jonathan Balcombe (29 May 2006). "Animals can be happy too". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Bestiality/Zoophilia: A Scarcely-Investigated Phenomenon Between Crime, Paraphilia, and Love". Scie-SocialCareOnline.org.uk. Archived 15 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Joseph W. Slade (2001). Pornography and Sexual Representation: A Reference Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 980. ISBN 978-0-313-31521-3.

- Bhatia, MS; Srivastava, S; Sharma, S (2005). "1. An uncommon case of zoophilia: A case report". Medicine, Science, and the Law. 45 (2): 174–75. doi:10.1258/rsmmsl.45.2.174. PMID 15895645. S2CID 5744962.

- Devlin, Hannah (10 January 2017). "Snow monkey attempts sex with deer in rare example of interspecies mating". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Monkey Tries to Mate With Deer in First Ever Video". Nationalgeographic.com. 11 January 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Wenzke, Marissa. "Sex between snow monkey and deer shows different species may mate if they're 'deprived', study says". Mashable.com. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Aggrawal, Anil (2009). "References to the paraphilias and sexual crimes in the Bible". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 16 (3): 109–14. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2008.07.006. PMID 19239958.

- Archaeometry.org, Link to web page and photograph, archaeometry.org

- Lynne Bevan (2006). Worshippers and warriors: reconstructing gender and gender relations in the prehistoric rock art of Naquane National Park, Valcamonica, Brecia, northern Italy. Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-84171-920-7.

- Paul G. Bahn (1998). The Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art. Cambridge University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-521-45473-5.

- Abuses Aberrations and Crimes of the Genital Sense, 1901.

- Marc Epprecht (2006). ""Bisexuality" and the politics of normal in African Ethnography". Anthropologica. 48 (2): 187–201. doi:10.2307/25605310. JSTOR 25605310.

- Masters, Robert E. L., Forbidden Sexual Behavior and Morality, p. 5.

- Vern L. Bullough; Bonnie Bullough (1 January 1994). Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8240-7972-7.

- Judith Worell (September 2001). "Cross-Cultural Sexual Practices". Encyclopedia of Women and Gender: Sex Similarities and Differences and the Impact of Society on Gender. Academic Press. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-12-227245-5.

- Voget, F. W. (1961) "Sex life of the American Indians", in Ellis, A. & Abarbanel, A. (Eds.) The Encyclopaedia of Sexual Behavior, Volume 1. London: W. Heinemann, pp. 90–109.

- Talayesva, Don C; Simmons, Leo William (1942). Sun Chief: The Autobiography of a Hopi Indian. Yale University Press. p. 78. ISBN 9780300002270. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- Masters (1962)

- Plummer, Keith (2001). To beast or not to beast: does the law of Christ forbid zoophilia?. 53rd National Conference of the Evangelical Theological Society. Colorado Springs, CO.

- Fordham.edu Aquinas on Unnatural Sex

- Swami Satya Prakash Saraswati, The Critical and Cultural Study of the Shatapatha Brahmana, p. 415.

- Podberscek, Anthony L.; Beetz, Andrea M. (1 September 2005). Bestiality and Zoophilia: Sexual Relations with Animals. Berg. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-85785-222-9. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Mani, Vettam (1975). Puranic Encyclopaedia: A Comprehensive Dictionary With Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 368–70. ISBN 978-0-8426-0822-0. OCLC 2198347.

- "Section 63 – Possession of extreme pornographic images". Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008. 2008.

- "Extreme Pornography". Crown Prosecution Service. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- Jackman, Myles (21 September 2015). "Is it illegal to have sex with a dead pig? Here's what the law says about the allegations surrounding David Cameron's biography". The Independent. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "New Hampshire HB1547 - 2016 - Regular Session". Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "§ 3 TierSchG - dejure.org". Dejure.org. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Sweden Joins An Increasing Number of European Countries That Ban Bestiality". Webpronews.com. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Flertal for lovændring: Nu bliver sex med dyr ulovligt". 21 April 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Diputados aclaran alcances y límites de la nueva Ley de Bienestar Animal". Elpais.cr. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "LEY No 700 del 01 de Junio de 2015 " Derechoteca". Derechoteca.com. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Transdoc :: Ley de Protección y Bienestar Animal :: transdoc.com". Transdoc.com. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Denmark passes law to ban bestiality". BBC Newsbeat. 22 April 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- https://lovinmalta.com/news/maltese-law-encouraging-animal-sex-tourism-and-risks-becoming-bestiality-hotspot/

- Howard Fischer: Lawmakers hope to outlaw bestiality, Arizona Daily Star, 28 March 2006. In Arizona, the motive for legislation was a "spate of recent cases."

- Posner, Richard, A Guide to America's Sex Laws, The University of Chicago Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-226-67564-0. Page 207.

- "TheLocal.se". TheLocal.se. 26 January 2012. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Crimes Act 1961 No 43 (as at 01 October 2012), Public Act – New Zealand Legislation". Legislation.govt.nz. 1 October 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- "Her Majesty the Queen v. D.L.W." Office of the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Canada (ORSCC). 2 May 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- Fred Leavitt (1 January 2003). The Real Drug Abusers. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-7425-2518-4.

female alpaca peru copulate.

- "Michigan State University College of Law". Animallaw.info. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- "Table of State Animal Sexual Assault Laws | Animal Legal & Historical Center". Animallaw.info. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Johnston, Lynda and Longhurst, Robyn Space, Place, and Sex Lanham, Maryland:2010 Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, p. 110.

- "Man dies after sex with horse". News24, 19 July 2005.

- "Sheriff says Craigslist facilitates bestiality". The Washington Times. 16 March 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Sessions, David (27 January 2010). "Bill to Criminalize Bestiality Advances in Alaska Legislature". Politics Daily. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2020.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Mandell, Nina (6 May 2011). "Legislation outlawing bestiality makes it to Florida governor's desk". Daily News. New York.

- "SB 151 - Alabama 2014 Regular Session". Openstate.org. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "New Jersey A3012 - 2014-2015 - Regular Session". Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Ohio SB195 - 2015-2016 - 131st General Assembly". Legiscan.com. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Texas: Crackdown on animal cruelty, bestiality, starts 1 Sept". Star-telegram.com. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "No. 62. An act relating to criminal justice" (PDF). Legislature.vermont.gov. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "AB391". Leg.state.nv.us. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Senate again passes bestiality bill | Florida Politics | Sun Sentinel blog". Weblogs.sun-sentinel.com. 24 March 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Bering, Jesse (24 March 2010). "Animal Lovers: Zoophiles Make Scientists Rethink Human Sexuality | Bering in Mind, Scientific American Blog Network". Scientific American. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- "Inter-disciplinary.net" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Roberts, Michael (2009). "The Unjustified Prohibition against Bestiality: Why the Laws in Opposition Can Find No Support under the Harm Principle". doi:10.2139/ssrn.1328310. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - An example digitized Tijuana Bible entitled The Pet from the 1960s is linked at tijuanabibles.org page link (also see full size and search).

- "The Dark Side of Porn Season 2 (2006) - Documentary / TV-Show". Crimedocumentary.com. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- EuroBabeIndex.com, Suzy Spark

- ‘Acts of depravity’ found on dad’s computer, Reading Post, 26 January 2011.

- W. Edward Craighead; Charles B. Nemeroff, eds. (11 November 2002). The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology and Behavioral Science. John Wiley & Sons. p. 1050. ISBN 978-0-471-27083-6.

- David Delaney (2003). Law and Nature. Cambridge University Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-139-43700-4.

- Montclair, 1997, cited by Miletski, 1999, p .35.

- Weinberg and Williams

- Markoff, 1990.

- Miletski p. 35.

- Miletski (1999)

- Milteski (1999), p. 35.

- Andriette, 1996.

- Fox, 1994.

- Montclair, 1997.

- Donofrio, 1996.

- Miletski (1999), p. 22.

- Thomas Francis (20 August 2009). "Those Who Practice Bestiality Say They're Part of the Next Sexual Rights Movement – Page 2 – News – Broward/Palm Beach – New Times Broward-Palm Beach". Broward/Palm Beach. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Pablo Stafforini. "Heavy Petting, by Peter Singer". Utilitarian.net. Archived from the original on 6 June 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Bestiality and Lack of Consent " StopBestiality". Stopbestiality.wordpress.com. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Other offences" (PDF). Protecting the Public: Strengthening Protection Against Sex Offenders and Reforming the Laws on Sexual Offences. 2002. pp. 32–3. ISBN 978-0-10-156682-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2013.

- Beetz 2002, section 5.2.8.

- Wesleyjsmith.com and Weeklystandard.com, 31 August 2005.

- Regan, Tom. Animal Rights, Human Wrongs. Rowman & Littlefield, 2003, pp. 63–4, 89.

- Sex Abuse Archived 14 December 2007 at Archive.today, NManimalControl.com

- "The First Strike Campaign: ANIMAL SEXUAL ABUSE FACT SHEET". NManimalControl.com. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Ascione, Frank R. (1993). "Children Who are Cruel to Animals: A Review of Research and Implications for Developmental Psychopathology". Anthrozoös: A Multidisciplinary Journal of the Interactions of People and Animals. 6 (4): 226–47. doi:10.2752/089279393787002105.

- by Lucas Wachob (28 February 2011). "Column: In defense of chicken 'lovers' – The Breeze: Columnists". Breezejmu.org. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Miltski, 1999, p. 50.

- Cauldwell, 1948 & 1968; Queen, 1997.

- Blake, 1971, and Greenwood, 1963, both cited in Miletski, 1999.

- Dekkers, 1994.

- (Einsenhaim, 1971, cited in Kathmandu, 2004)"

- Singer, Peter. Heavy Petting, Nerve, 2001.

- Pablo Stafforini. "Utilitarian.com". Utilitarian.com. Archived from the original on 6 June 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Ruetenik, T. (2010). "Animal Liberation or Human Redemption: Racism and Speciesism in Toni Morrison's Beloved". Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment. 17 (2): 317–326. doi:10.1093/isle/isq034.

- Boggs, Colleen Glenney (Fall 2010). "American Bestiality: Sex, Animals, and the Construction of Subjectivity". Cultural Critique. 76 (76): 98–125. doi:10.1353/cul.2010.0020 (inactive 14 January 2021). JSTOR 40925347.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- "Interspecies Sex: Evolution's Hidden Secret?". News.nationalgeographic.com. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Changing Perspectives of Bestiality: Breaking the Human-Animal Distinction to Violating Animal Rights" (PDF). Stanford.edu. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- Maratea, R. J. (2011). "Screwing the Pooch: Legitimizing Accounts in a Zoophilia On-line Community". Deviant Behavior. 32 (10): 918–943. doi:10.1080/01639625.2010.538356. S2CID 145637418.

- Aldo Poiani; A. F. Dixson (19 August 2010). Animal Homosexuality: A Biosocial Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-139-49038-2.

- Danish Animal Ethics Council report Archived 9 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Udtalelse om menneskers seksuelle omgang med dyr published November 2006. Council members included two academics, two farmers/smallholders, and two veterinary surgeons, as well as a third veterinary surgeon acting as secretary.

- "Bid to save over-friendly dolphin". CNN. 28 May 2002. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012.

- "OFCOM Broadcasting Code". Ofcom.org.uk. 28 February 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

External links

| Look up zoophilia, zoosexuality, or bestiality in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zoophilia. |

- Encyclopedia of Human Sexuality entry for "Bestiality" at Sexology Department of Humboldt University, Berlin.

- Zoophilia References Database Bestiality and zoosadism criminal executions.

- Animal Abuse Crime Database search form for the U.S. and UK.