1812 United Kingdom general election

The 1812 United Kingdom general election was the fourth general election to be held after the Union of Great Britain and Ireland.

| ||||||||||||||||

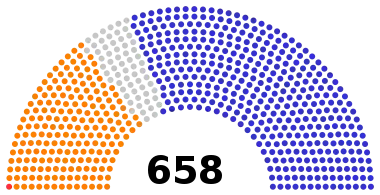

All 658 seats in the House of Commons 330 seats needed for a majority | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

The UK parliament after the 1812 election | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

The fourth United Kingdom Parliament was dissolved on 29 September 1812. The new Parliament was summoned to meet on 24 November 1812, for a maximum seven-year term from that date. The maximum term could be and normally was curtailed, by the monarch dissolving the Parliament, before its term expired.

Political situation

Following the 1807 election the Pittite Tory ministry, led as Prime Minister by the Duke of Portland (who still claimed to be a Whig), continued to prosecute the Napoleonic Wars.

At the core of the opposition were the Foxite Whigs, led since the death of Fox in 1806 by Earl Grey (known by the courtesy title of Viscount Howick and a member of the House of Commons from 1806–07). However, as Foord observes: "the affairs of the party during most of this period were in a state of uncertainty and confusion". Grey was not the commanding leader Fox had been. After Grey inherited his peerage and went to the House of Lords in 1807, the party leadership in the House of Commons was extremely weak.

The Grenvillites, associated with the Whig Prime Minister before Portland, William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville, were also in opposition but were of less significance than the Foxites. Despite this Grenville was recognised as the first Leader of the Opposition in the House of Lords.

A relative of Grey's wife, George Ponsonby, was proposed to Whig MPs by Grey and Grenville as the Whig leader in the House of Commons. Ponsonby was the first person recognised as the official Leader of the Opposition in the House of Commons, as opposed to the leader of an opposition faction. He proved to be incompetent but could not be persuaded to resign.

Until 1812 the Tory faction associated with another former Prime Minister, Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth, and were also out of office.

The smallest component of the opposition were the Radicals, who were a largely middle-class group of reformers. They had philosophical differences with the more aristocratic Whigs, but usually ended up voting with them in Parliament.

In 1809 Portland, whose health was failing, resigned. The new Tory Prime Minister was Spencer Perceval. In April 1812 he brought Sidmouth into the cabinet. A month later, on 11 May 1812, Perceval was assassinated. The premiership passed to the Earl of Liverpool, who failed to attract Grenville. This was a further stage in the development of a two-party system—just about all Tories supported the government and all Whigs opposed it.

The general election of 1812 returned the Tories to power for another term.

Dates of election

At this period there was not one election day. After receiving a writ (a royal command) for the election to be held, the local returning officer fixed the election timetable for the particular constituency or constituencies he was concerned with. Polling in seats with contested elections could continue for many days.

An example of what happened in the 1812 election was the Irish constituency of Westmeath. Walker confirms the date of election was 24 October 1812. Stooks Smith indicates that there were three days of polling, during which time 950 electors came to the hustings and voted. Longer contests were possible. The polling in the Berkshire election of 1812 went on for 15 days (with 1,992 electors voting).

The time between the first and last contests in the general election was 5 October to 10 November 1812.

Summary of the constituencies

Monmouthshire (1 County constituency with 2 MPs and one single member Borough constituency) is included in Wales in these tables. Sources for this period may include the county in England.

Table 1: Constituencies and MPs, by type and country

| Country | BC | CC | UC | Total C | BMP | CMP | UMP | Total MPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 202 | 39 | 2 | 243 | 404 | 78 | 4 | 486 | |

| 13 | 13 | 0 | 26 | 13 | 14 | 0 | 27 | |

| 15 | 30 | 0 | 45 | 15 | 30 | 0 | 45 | |

| Ireland | 33 | 32 | 1 | 66 | 35 | 64 | 1 | 100 |

| Total | 263 | 114 | 3 | 380 | 467 | 176 | 5 | 658 |

Table 2: Number of seats per constituency, by type and country

| Country | BCx1 | BCx2 | BCx4 | CCx1 | CCx2 | UCx1 | UCx2 | Total C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 196 | 2 | 0 | 39 | 0 | 2 | 243 | |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 26 | |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45 | |

| Ireland | 31 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 1 | 0 | 66 |

| Total | 63 | 198 | 2 | 42 | 72 | 1 | 2 | 380 |

See also

References

- His Majesty's Opposition 1714–1830, by Archibald S. Foord (Oxford University Press 1964)

- (Dates of Elections) Footnote to Table 5.02 British Electoral Facts 1832–1999, compiled and edited by Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher (Ashgate Publishing Ltd 2000).

- (Types of constituencies – Great Britain) British Historical Facts 1760–1830, by Chris Cook and John Stevenson (The Macmillan Press 1980).

- (Types of constituencies – Ireland) Parliamentary Election Results in Ireland 1801–1922, edited by B.M. Walker (Royal Irish Academy 1978).

.jpg.webp)