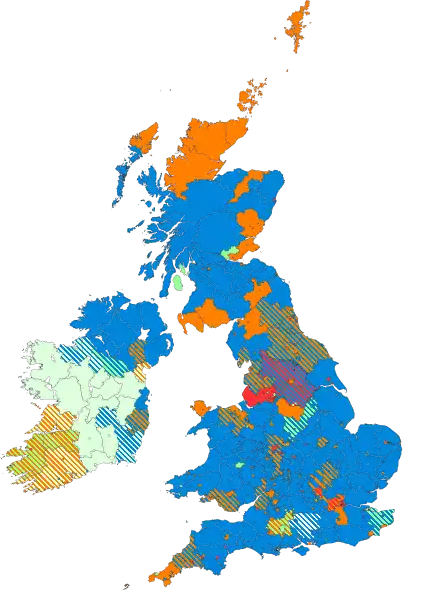

1852 United Kingdom general election

The 1852 United Kingdom general election was a watershed in the formation of the modern political parties of Britain. Following 1852, the Tory/Conservative party became, more completely, the party of the rural aristocracy, while the Whig/Liberal party became the party of the rising urban bourgeoisie in Britain. The results of the election were extremely close in terms of the numbers of seats won by the two main parties.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

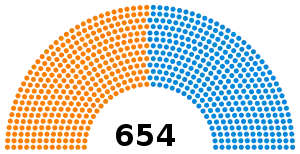

All 654 seats in the House of Commons 328 seats needed for a majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Colours denote the winning party—as shown in § Results | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As in the previous election of 1847, Lord John Russell's Whigs won the popular vote, but the Conservative Party won a very slight majority of the seats. However, a split between Protectionist Tories, led by the Earl of Derby, and the Peelites who supported Lord Aberdeen made the formation of a majority government very difficult. Lord Derby's minority, protectionist government ruled from 23 February until 17 December 1852. Derby appointed Benjamin Disraeli as Chancellor of the Exchequer in this minority government. However, in December 1852, Derby's government collapsed because of issues arising out of the budget introduced by Disraeli. A Peelite–Whig-Radical coalition government was then formed under Lord Aberdeen. Although the immediate issue involved in this vote of "no confidence" which caused the downfall of the Derby minority government was the budget, the real underlying issue was repeal of the Corn Laws which Parliament had passed in June 1846.

|

|

|

Corn Laws

A group within the Tory/Conservative Party called the "Peelites" voted with the Whigs to achieve the repeal of the Corn Laws. The Peelites were so named because they were followers of Prime Minister Robert Peel. In June 1846, when Peel was the Prime Minister of a Tory government, he led a group of Tory/Conservatives to vote with the minority Whigs against a majority of his own party.

"Corn" was important to the cost of living of the average person in Britain during the early 19th century. The term "corn" did not refer to maize, as it did in the United States. In Britain, "corn" refers to wheat, rye and/or other grains. Wheat, or corn, was used in the baking of bread and was the "staff of life". Thus the price of wheat was a very substantial part of the cost of living. The Corn Laws enforced a very high "protective" tariff against the importation of wheat into England. These high tariffs raised the cost of living and increased the suffering of poor people in England. Agitation for the repeal of the Corn Laws had begun in England as early as 1837, and bills for their repeal had been introduced in Parliament each year from 1837 until their actual repeal in 1847.

Split in the Tory party

For some parliamentary leaders, like John Bright, Richard Cobden and Charles Pelham Villiers, the repeal of tariffs on imported corn was not enough. They wished to reduce the tariffs on all imported consumer products. These parliamentary leaders became known as "free traders". The repeal of the Corn Laws irrevocably split the Tory/Conservative party. The Peelites were not free traders, but both the Peelites and the free traders were originally Tories. Thus both the free traders and the Peelites tended to side with the Whigs against the Tories on international trade issues. This presented a real threat to any government the Tories attempted to form. The effect of this split was felt in the election of July–August 1847, when the Whig party won a 53.8% majority of seats in Parliament. The Whigs knew that they could count on the Peelite Conservatives when an international trade issue came before Parliament. In June 1852, the effects of the split in the Tory/Conservative party was having even more effect.

The period 1847–48 had been one of economic stagnation in Britain, but 1849–52 saw a return to prosperity.[2] Indeed, 1852 proved to be "one of the most signal years of prosperity England ever enjoyed".[3] The Whigs and Peelites felt that the repeal of the Corn Laws had brought about the prosperity, and wished to take credit for this. The Free Traders agreed, and continued to press for the repeal of all tariffs on consumer goods to achieve continued prosperity.

Ministerialists and Oppositionists

The split in the Tory party was a significant cause of the reformation of the political parties in Britain in the February 1852 election. To understand this, it may be easier to consider the British political party structure in 1852 by using the labels "Ministerialists" (the protectionist Tory/Conservatives) and the Oppositionists (the Whigs, Free Traders and Peelites).[4]

As noted above, in the election of 1852 the Ministerialists became the party of the rural landholders, while the Oppositionists became the party of the towns, boroughs and growing urban industrial areas of Britain. In the 1852 election, the borough constituencies of England elected 104 Ministerialists to Parliament and 215 Oppositionists; while the (more rural) county constituencies of England elected 109 Ministerialists and only 32 Oppositionists.[4] There were similar results in Wales and Scotland: the boroughs of Wales elected 10 Oppositionists and only 3 Ministerialists, while the counties of Wales elected 11 Ministerialists and 3 Oppositionists.[4] The Scottish boroughs elected 25 Oppositionalists and not a single Ministerialist, while Scottish counties elected 14 Ministerialists and 13 Oppositionists.[4] Only in Ireland was this political formation less clear-cut, as the boroughs in Ireland elected 14 Ministerialists and 25 Oppositionists,[5] while the counties of Ireland elected 24 Ministerialsts and 35 Oppositionists.[5] The Irish Oppositionists were known as the "Irish Brigade".

Fall of the government in December 1852

Although the Ministerialists, elected in 1852, were initially loyal to the Tory/Conservatives, the Irish Brigade knew that they would be able to count on support from some of the Irish Ministerialists if and when a purely Irish issue arose in Parliament. The Irish were seeking tenant rights for Ireland.[6] An opportunity for the Irish Oppositionists to pull some Irish Ministerialists over to the Opposition arose in December 1852 when the Chancellor of Exchequer, Benjamin Disraeli, introduced the budget of the Derby minority government. This budget imposed a number of tax increases on the profits of the rising bourgeoisie and granted a number of tax cuts for the rural landed aristocracy.[7] This budget also extended the income tax to the Irish bourgeoisie, thus angering some of the Irish Ministerialists who had been supporting the minority government.[7] Consequently, a number of Irish Ministerialists voted against the minority government on the Disraeli budget on 17 December 1852. This vote of "no confidence" caused the government to fall.[8]

Following the fall of the minority government, Lord Aberdeen was called on to form a government, and he formed a Peelite/Whig government on 19 December 1852. This government served until 30 January 1855, when it too collapsed due to issues surrounding British involvement in the Crimean War.

Results

| UK general election 1852 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidates | Votes | |||||||||||||

| Stood | Elected | Gained | Unseated | Net | % of total | % | No. | Net % | |||||||

| Conservative | 461 | 330 | +5 | 50.46 | 41.87 | 311,481 | −0.5 | ||||||||

| Whig | 488 | 324 | +32 | 49.54 | 57.92 | 430,882 | +4.1 | ||||||||

| Chartist | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 0.21 | 1,541 | +0.1 | ||||||

While the Conservatives had, in theory, a slim majority over the Whigs, the party was divided between Protectionist and Peelite wings: the former numbered about 290 and the latter 35–40. The Whigs themselves represented a coalition of Whigs, Liberals, Radicals, and Irish nationalists. The above numbers therefore do not represent the true balance of support in Parliament.

Voting summary

Seats summary

Notes

- Including Peelites. The Peelite faction elected 45 MPs, 28 in England, 6 in Wales, 8 in Scotland and 3 in Ireland.

- Marx, p. 358: "Pauperism and Free Trade – The Approaching Commercial Crisis"

- Marx, p. 359: "Pauperism and Free Trade – The Approaching Commercial Crisis"

- Marx, p. 348: "Result of the Elections"

- Marx, p. 349: "Result of the Elections"

- Marx, p. 668, note 236

- Marx, p. 462: "Parliament – Vote of November 26 – Disraeli's Budget"

- Marx, p. 474: "Superannuated Administration – Prospects of the Coalition Ministry"

References

- Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, 11, New York: International Publishers, 1979

- Craig, F. W. S. (1989), British Electoral Facts: 1832–1987, Dartmouth: Gower, ISBN 0900178302

- Rallings, Colin; Thrasher, Michael, eds. (2000), British Electoral Facts 1832–1999, Ashgate Publishing Ltd

.jpg.webp)