1865 United Kingdom general election

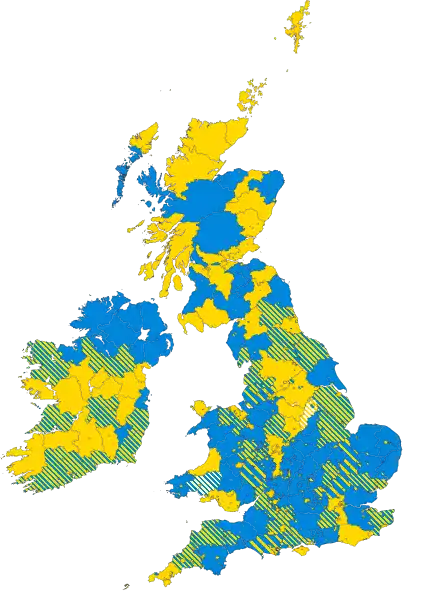

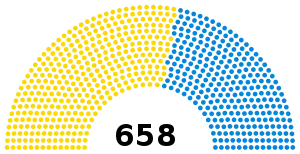

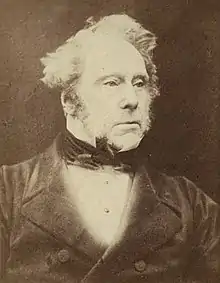

The 1865 United Kingdom general election saw the Liberals, led by Lord Palmerston, increase their large majority over the Earl of Derby's Conservatives to 80. The Whig Party changed its name to the Liberal Party between the previous election and this one.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 658 seats in the House of Commons 330 seats needed for a majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Colours denote the winning party—as shown in § Results | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Palmerston died in October the same year and was succeeded by Lord John Russell as Prime Minister.[1] Despite the Liberal majority, the party was divided by the issue of further parliamentary reform, and Russell resigned after being defeated in a vote in the House of Commons in 1866, leading to minority Conservative governments under Derby and then Benjamin Disraeli.

This was the last United Kingdom general election until 2019 where a party increased its majority after having been returned to office at the previous election with a reduced majority.

|

Corruption

The 1865 general election was regarded by contemporaries as being a generally dull contest nationally, which exaggerated the degree of corruption within individual constituencies. In his PhD thesis, Cornelius O'Leary described The Times as having reported "the testimony is unanimous that in the General Election of 1865 there was more profuse and corrupt expenditure than was ever known before".[2] As a result of allegations of corruption, 50 election petitions were lodged, of which 35 were pressed to a trial; 13 ended with the elected MP being unseated. In four cases a Royal Commission had to be appointed because of widespread corrupt practices in the constituency.[3]

As a result, when he became Prime Minister in 1867, Benjamin Disraeli announced that he would introduce a new method for election petition trials, which were then determined by a committee of the House of Commons, resulting in the Parliamentary Elections Act 1868, whereby two Judges of the Court of Common Pleas, Exchequer of Pleas or Queen's Bench would be designated to try election petitions with full judicial salaries.[3]

Constituencies

Many new constituencies were used for this election:

Results

| 369 | 289 |

| Liberal | Conservative |

| UK General Election 1865 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidates | Votes | |||||||||||||

| Stood | Elected | Gained | Unseated | Net | % of total | % | No. | Net % | |||||||

| Liberal | 516 | 369 | +13 | 56.08 | 59.52 | 508,821 | −6.2 | ||||||||

| Conservative | 406 | 289 | −9 | 43.92 | 40.48 | 346,035 | +6.2 | ||||||||

| Total | 658 | +4 | 100 | 100 | 854,856 | ||||||||||

Great Britain

| Party | Candidates | Unopposed | Seats | Seats change | Votes | % | % change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 433 | 133 | 311 | 457,289 | 60.0 | |||

| Conservative | 347 | 115 | 244 | 304,538 | 40.0 | |||

| Total | 780 | 248 | 555 | 761,827 | 100 | |||

England

| Party | Candidates | Unopposed | Seats | Seats change | Votes | % | % change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 359 | 88 | 251 | 406,978 | 59.0 | |||

| Conservative | 308 | 94 | 213 | 291,238 | 41.0 | |||

| Total | 667 | 182 | 464 | 698,216 | 100 | |||

Scotland

| Party | Candidates | Unopposed | Seats | Seats change | Votes | % | % change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 51 | 30 | 42 | 43,480 | 85.4 | |||

| Conservative | 17 | 7 | 11 | 4,305 | 14.6 | |||

| Total | 68 | 37 | 53 | 47,785 | 100 | |||

Wales

| Party | Candidates | Unopposed | Seats | Seats change | Votes | % | % change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 21 | 15 | 18 | 4,565 | 74.0 | |||

| Conservative | 16 | 12 | 14 | 1,600 | 26.0 | |||

| Total | 37 | 27 | 32 | 6,165 | 100 | |||

Ireland

| Party | Candidates | Unopposed | Seats | Seats change | Votes | % | % change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 83 | 28 | 58 | 51,532 | 55.6 | |||

| Irish Conservative | 59 | 27 | 45 | 41,497 | 44.4 | |||

| Total | 142 | 55 | 103 | 93,029 | 100 | |||

Universities

| Party | Candidates | Unopposed | Seats | Seats change | Votes | % | % change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | 6 | 2 | 6 | 7,395 | 76.5 | |||

| Liberal | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2,266 | 23.5 | |||

| Total | 8 | 2 | 6 | 9,661 | 100 | |||

Source: Rallings & Thrasher 2012, pp. 8–9

References

- Everett 2006.

- Kelly & Hamlyn 2013, p. 93.

- O'Leary 1962, pp. 27–28, 39.

Sources

- Craig, F. W. S. (1989), British Electoral Facts: 1832–1987, Dartmouth: Gower, ISBN 0900178302

- Crewe, Ivor (2006), "New Labour's Hegemony: Extension or Erosion?", in Bartle, John; King, Anthony (eds.), Britain at the Polls 2005, Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, p. 204

- Everett, Jason M., ed. (2006), "1865", The People's Chronology, Thomson Gale, archived from the original on 6 August 2007, retrieved 12 May 2007

- Kelly, Richard; Hamlyn, Matthew (2013), "The Law and Conduct of MPs", in Horne, Alexander; Drewry, Gavin; Oliver, Dawn (eds.), Parliament and the Law, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 978-1-7822-5258-0

- O'Leary, Cornelius (1962), The Elimination of Corrupt Practices in British Elections 1868–1911, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Rallings, Colin; Thrasher, Michael, eds. (2000), British Electoral Facts 1832–1999, Ashgate Publishing Ltd

- Rallings, Colin; Thrasher, Michael, eds. (2012), British Electoral Facts 1832–2012, London: Biteback, ISBN 978-1-84954-134-3

.jpg.webp)