Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey

Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, KG, PC (13 March 1764 – 17 July 1845), known as Viscount Howick between 1806 and 1807, was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from November 1830 to July 1834. A scion of the noble House of Grey and a member of the Whig Party, his government enacted the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1833.

He was a long-time leader of multiple reform movements, most famously that of parliamentary reform, which led to the Reform Act 1832. Grey was a strong opponent of the foreign and domestic policies of William Pitt the Younger in the 1790s. In 1807, he resigned as Foreign Secretary to protest against King George III's uncompromising rejection of Catholic Emancipation. Grey finally resigned in 1834 over disagreements in his cabinet regarding Ireland, and retired from politics. Scholars rank him highly among British prime ministers, believing that he averted much civil strife and enabled Victorian progress.[1] Earl Grey tea is named after him.[2]

Early life

Descended from a long-established Northumbrian family seated at Howick Hall, Grey was the second but eldest surviving son of General Charles Grey KB (1729–1807) and his wife, Elizabeth (1743/4–1822), daughter of George Grey of Southwick, co. Durham. He had four brothers and two sisters. He was educated at Richmond School,[3] followed by Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge,[4] acquiring a facility in Latin and in English composition and declamation that enabled him to become one of the foremost parliamentary orators of his generation.

Titles

He became the second Earl Grey, Viscount Howick and Baron Grey of Howick on 14 November 1807 upon the death of his father. Upon the death of his uncle on 30 March 1808 he became the third Baronet Grey of Howick.

Government career

Elected to Parliament, 1786

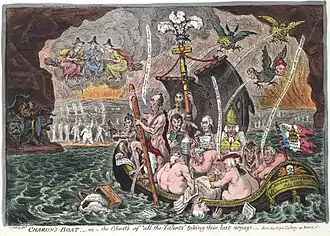

Grey was elected to Parliament for the Northumberland constituency on 14 September 1786, aged just 22. He became a part of the Whig circle of Charles James Fox, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and the Prince of Wales, and soon became one of the major leaders of the Whig party. He was the youngest manager on the committee for prosecuting Warren Hastings. The Whig historian T. B. Macaulay wrote in 1841:

At an age when most of those who distinguish themselves in life are still contending for prizes and fellowships at college, he had won for himself a conspicuous place in Parliament. No advantage of fortune or connection was wanting that could set off to the height his splendid talents and his unblemished honour. At twenty-three he had been thought worthy to be ranked with the veteran statesmen who appeared as the delegates of the British Commons, at the bar of the British nobility. All who stood at that bar, save him alone, are gone, culprit, advocates, accusers. To the generation which is now in the vigour of life, he is the sole representative of a great age which has passed away. But those who, within the last ten years, have listened with delight, till the morning sun shone on the tapestries of the House of Lords, to the lofty and animated eloquence of Charles Earl Grey, are able to form some estimate of the powers of a race of men among whom he was not the foremost.[5]

%252C_by_Henry_Bone.jpg.webp)

Grey was also noted for advocating Parliamentary reform and Catholic emancipation. His affair with Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, herself an active political campaigner, did him little harm although it nearly caused her to be divorced by her husband.

Foreign Secretary, 1806–1807

In 1806, Grey, by then Lord Howick owing to his father's elevation to the peerage as Earl Grey, became a part of the Ministry of All the Talents (a coalition of Foxite Whigs, Grenvillites, and Addingtonites) as First Lord of the Admiralty.

Following Fox's death later that year, Howick took over both as Foreign Secretary and as leader of the Whigs. The ministry broke up in 1807 when George III blocked Catholic Emancipation legislation and required that all ministers individually sign a pledge, which Howick refused to do, that they would not "propose any further concessions to the Catholics".[6]

Years in opposition, 1807–1830

The government fell from power the next year, and, after a brief period as a member of parliament for Appleby from May to July 1807, Howick went to the Lords, succeeding his father as Earl Grey. He continued in opposition for the next 23 years. There were times during this period when Grey came close to joining the Government. In 1811, the Prince Regent tried to court Grey and his ally William Grenville to join the Spencer Perceval ministry following the resignation of Lord Wellesley. Grey and Grenville declined because the Prince Regent refused to make concessions regarding Catholic Emancipation.[7] Grey's relationship with the Prince was strained further when his estranged daughter and heiress, Princess Charlotte, turned to him for advice on how to avoid her father's choice of husband for her.[8]

On the Napoleonic Wars, Grey took the standard Whig party line. After being initially enthused by the Spanish uprising against Napoleon, Grey became convinced of the French emperor's invincibility following the defeat and death of Sir John Moore, the leader of the British forces in the Peninsular War.[9] Grey was then slow to recognise the military successes of Moore's successor, the Duke of Wellington.[10] When Napoleon first abdicated in 1814, Grey objected to the restoration of the Bourbons' authoritarian monarchy; and when Napoleon was reinstalled the following year, he said that the change was an internal French matter.[11]

In 1826, believing that the Whig party no longer paid any attention to his opinions, Grey stood down as leader in favour of Lord Lansdowne.[12] The following year, when George Canning succeeded Lord Liverpool as Prime Minister, it was therefore Lansdowne and not Grey who was asked to join the Government, which needed strengthening following the resignations of Robert Peel and the Duke of Wellington.[13] When Wellington became Prime Minister in 1828, George IV (as the Prince Regent had become) singled out Grey as the one person he could not appoint to the Government.[14]

Prime Minister (1830–1834) and Great Reform Act 1832

In 1830, following the death of George IV and when the Duke of Wellington resigned on the question of Parliamentary reform, the Whigs finally returned to power, with Grey as Prime Minister. In 1831, he was made a member of the Order of the Garter. His term was a notable one, seeing passage of the Reform Act 1832, which finally saw the reform of the House of Commons, and the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833. As the years had passed, however, Grey had become more conservative, and he was cautious about initiating more far-reaching reforms, particularly since he knew that the King was at best only a reluctant supporter of reform.

Grey contributed to a plan to found a new colony in South Australia: in 1831 a "Proposal to His Majesty's Government for founding a colony on the Southern Coast of Australia" was prepared under the auspices of Robert Gouger, Anthony Bacon, Jeremy Bentham and Grey, but its ideas were considered too radical, and it was unable to attract the required investment.[15] In the same year, Grey was appointed to serve on the Government Commission upon Emigration (which was wound up in 1832).[16]

It was the issue of Ireland which precipitated the end of Grey's premiership in 1834. Lord Anglesey, the Viceroy of Ireland, preferred conciliatory reform including the partial redistribution of the income from the church tithe to the Catholic church and away from the established Protestant one, a policy known as "appropriation".[17] The Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Stanley, however, preferred coercive measures.[18] The cabinet was divided and when Lord John Russell drew attention in the House of Commons to their differences over appropriation, Stanley and others resigned.[19] This triggered Grey to retire from public life, leaving Lord Melbourne as his successor. Unlike most politicians, he seems to have genuinely preferred a private life; colleagues remarked caustically that he threatened to resign at every setback.

Grey returned to Howick but kept a close eye on the policies of the new cabinet under Melbourne, whom he, and especially his family, regarded as a mere understudy until he began to act in ways of which they disapproved. Grey became more critical as the decade went on, being particularly inclined to see the hand of Daniel O'Connell behind the scenes and blaming Melbourne for subservience to the Radicals with whom he identified the Irish patriot. He made no allowances for Melbourne's need to keep the radicals on his side to preserve his shrinking majority in the Commons, and in particular he resented any slight on his own great achievement, the Reform Act, which he saw as a final solution of the question for the foreseeable future. He continually stressed its conservative nature. As he declared in his last great public speech, at the Grey Festival organised in his honour at Edinburgh in September 1834, its purpose was to strengthen and preserve the established constitution, to make it more acceptable to the people at large, and especially the middle classes, who had been the principal beneficiaries of the Reform Act, and to establish the principle that future changes would be gradual, "according to the increased intelligence of the people, and the necessities of the times".[20] It was the speech of a conservative statesman.[21]

Lord Grey's ministry, November 1830 – July 1834

- Lord Grey — First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of Lords

- Lord Brougham — Lord Chancellor

- Lord Lansdowne — Lord President of the Council

- Lord Durham — Lord Privy Seal

- Lord Melbourne — Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Lord Palmerston — Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Lord Goderich — Secretary of State for War and the Colonies

- Sir James Graham — First Lord of the Admiralty

- Lord Althorp — Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons

- Charles Grant — President of the Board of Control

- Lord Holland — Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- The Duke of Richmond — Postmaster-General

- Lord Carlisle — Minister without Portfolio

Changes

- June 1831 — Lord John Russell, the Paymaster of the Forces, and Edward Smith-Stanley, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, join the Cabinet.

- April 1833 — Lord Goderich, now Lord Ripon, succeeds Lord Durham as Lord Privy Seal. Edward Smith-Stanley succeeds Ripon as Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. His successor as Chief Secretary for Ireland is not in the Cabinet. Edward Ellice, the Secretary at War, joins the Cabinet.

- June 1834 — Thomas Spring Rice succeeds Stanley as Colonial Secretary. Lord Carlisle succeeds Ripon as Lord Privy Seal. Lord Auckland succeeds Graham as First Lord of the Admiralty. The Duke of Richmond leaves the Cabinet. His successor as Postmaster-General is not in the Cabinet. Charles Poulett Thomson, the President of the Board of Trade, and James Abercrombie, the Master of the Mint, join the Cabinet.

Personal life

.jpg.webp)

On 18 November 1794, Grey married Hon. Mary Elizabeth Ponsonby (1776–1861), only daughter of William Ponsonby, 1st Baron Ponsonby of Imokilly and Hon. Louisa Molesworth. The marriage was a fruitful one; between 1796 and 1819 the couple had ten sons and six daughters:

- unnamed daughter Grey (stillborn, 1796)

- Lady Louisa Elizabeth Grey (7 April 1797 – 26 November 1841). She married John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, on 9 December 1816. They had five children, including Charles William, Grey's favourite grandson, who died young.

- Lady Elizabeth Grey (10 July 1798 – 8 November 1880). She married John Crocker Bulteel on 13 May 1826. They had five children.

- Lady Caroline Grey (30 August 1799 – 28 April 1875). She married Captain Hon. George Barrington on 15 January 1827. They had two children

- Lady Georgiana Grey (17 February 1801 – 13 September 1900), who never married.

- Henry George Grey, 3rd Earl Grey (28 December 1802 – 9 October 1894). He married Maria Copley on 9 August 1832.

- General Charles Grey (15 March 1804 – 31 March 1870). He married Caroline Farquhar on 26 July 1836. They had seven children, including Albert Grey, 4th Earl Grey.

- Admiral Sir Frederick William Grey (23 August 1805 – 2 May 1878). He married Barbarina Sullivan on 20 July 1846.

- Lady Mary Grey (2 May 1807 – 6 July 1884). She married Charles Wood, 1st Viscount Halifax, on 29 July 1829. They had seven children.

- The Honourable William Grey (13 May 1808 – 11 February 1815), who died at the age of six.

- Admiral The Honourable George Grey (16 May 1809 – 3 October 1891). He married Jane Stuart (daughter of General Hon. Sir Patrick Stuart) on 20 January 1845. They had eleven children.

- Thomas Grey (29 December 1810 – 8 July 1826), who died at the age of fifteen.

- Rev. John Grey MA, DD, Canon and Rector of Durham (2 March 1812 – 11 November 1895). He married Lady Georgiana Hervey (daughter of Frederick William Hervey, 1st Marquess of Bristol) in July 1836. They had three children. He remarried Helen Spalding (maternal granddaughter of John Henry Upton, 1st Viscount Templetown) on 11 April 1874.

- Reverend Francis Richard Grey (31 March 1813 – 22 March 1890). He married Lady Elizabeth Howard, daughter of George Howard, 6th Earl of Carlisle on 12 August 1840.

- Captain the Hon. Henry Cavendish Grey (16 October 1814 – 5 September 1880)

- William George Grey (15 February 1819 – 19 December 1865). He married Theresa Stedink on 20 September 1858.

He also had an illegitimate daughter with the Duchess of Devonshire:

- Eliza Courtney (20 February 1792 – 2 May 1859). She married General Robert Ellice on 10 December 1814.

Relationship with Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire

While Mary was frequently pregnant during their marriage and remained at home, Grey travelled alone and had affairs with other women. Before he married Mary, his engagement to her nearly suffered because of his affair with Georgiana Cavendish. The young Grey met Georgiana sometime in the late 1780s to early 1790s while attending a Whig society meeting in Devonshire House. Grey and Georgiana became lovers, and in 1791 she became pregnant. Grey wanted Georgiana to leave her husband the duke and live with him, but the duke told Georgiana if she did, she would never see her children again. Georgiana was sent to France where, on 20 February 1792 in Aix-en-Provence, she gave birth to a daughter, whom she named Eliza Courtney. She returned to England with the child in September 1793, and entrusted her to Grey's parents, who raised her as though she were his sister.

Georgiana and Charles spent time with their daughter, who was informed of her true parentage some time after Georgiana's death in 1806. She married General Robert Ellice. Her maternal aunt, Henrietta Ponsonby, Countess of Bessborough, visited the Greys in 1808 (without knowing she was Eliza's aunt) and later wrote of her strange observations in which she stated "he (Charles) seems very fond of her". Eliza later named her eldest daughter Georgiana and her youngest child Charles.

Later years

Grey spent his last years in contented, if sometimes fretful, retirement at Howick with his books, his family, and his dogs. The one great personal blow he suffered in old age was the death of his favourite grandson, Charles, at the age of 13. Grey became physically feeble in his last years and died quietly in his bed on 17 July 1845, forty-four years to the day since going to live at Howick.[22] He was buried in the Church of St Michael and All Angels there on the 26th in the presence of his family, close friends, and the labourers on his estate.[21]

His biographer G. M. Trevelyan argues:

in our domestic history 1832 is the next great landmark after 1688 ... [It] saved the land from revolution and civil strife and made possible the quiet progress of the Victorian era.[23]

In popular culture

Charles Grey is portrayed by Dominic Cooper in the 2008 film The Duchess, directed by Saul Dibb and starring Keira Knightley and Ralph Fiennes. The film is based on Amanda Foreman's biography of Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire.

Commemoration and tea

Earl Grey tea, a blend which uses bergamot oil to flavour the brew, is named after Grey.[24]

Grey is commemorated by Grey's Monument in the centre of Newcastle upon Tyne, which consists of a statue of Lord Grey standing atop a 40 m (130 ft) high column.[25] The monument was damaged by lightning in 1941 and the statue's head was knocked off.[26] The monument lends its name to Monument Metro station on the Tyne and Wear Metro, located directly underneath.[27] Grey Street in Newcastle upon Tyne, which runs southeast from the monument, is also named after Grey.[28]

Durham University's Grey College is named after Grey, who as Prime Minister in 1832 supported the Act of Parliament that established the university.[29]

References

- Paul Strangio; Paul 't Hart; James Walter, eds. (2013). Understanding Prime-Ministerial Performance: Comparative Perspectives. Oxford University Press. p. 225. ISBN 9780199666423.

- Kramer, Ione. All the Tea in China. China Books, 1990. ISBN 0-8351-2194-1. pp. 180–181.

- "Info" (PDF). fretwell.kangaweb.com.au.

- "Grey, Charles (GRY781C)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Thomas Babington Macaulay, ‘Warren Hastings’, Edinburgh Review LXXIV (October 1841), pp. 160–255.

- Smith 1996, p. 125

- Smith, E.A. (1996). Lord Grey 1764–1845. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Alan Sutton Publishing Limited. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-0750911276.

- Smith (paperback) 1996, pp. 222–226

- Smith (paperback) 1996, pp. 169–171

- Smith (paperback) 1996, pp. 172–174

- Smith, 1996 pp 176–8

- Smith (paperback) 1996, pp. 240–241

- Smith (paperback) 1996, pp. 241–242

- Smith, 1996 pp245-6

- "Foundation of the Province". SA Memory. State Library of South Australia. 5 February 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "Emigration from the United Kingdom" (PDF). Journal of the Statistical Society of London. 1 (3): 156-157. July 1838. doi:10.2307/2337910. JSTOR 2337910 – via JSTOR.

- Smith (paperback) 1996, pp. 288–293

- Smith (paperback) 1996, p. 301

- Smith (paperback) 1996, pp. 304–305

- Edinburgh Weekly Journal, 17 September 1834

- E. A. Smith, 'Grey, Charles, second Earl Grey (1764–1845)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, May 2009, accessed 13 February 2010.

- GRO Register of Deaths: SEP 1845 XXV 130 ALNWICK

- Peter Brett, "Grey, Charles, 2nd Earl Grey" in D. M. Loades, ed. (2003). Reader's guide to British history. p. 1:586. ISBN 9781579584269.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Wallop, Harry (28 March 2011). "Lady Grey tea: fact file". Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- Historic England. "Earl Grey Monument (1329931)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- David Morton (18 March 2015). "How the statue on Grey's Monument was struck by lightning and lost its head". ChronicleLive.

- "Tyne and Wear Metro : Stations : Monument". the teams.co.uk. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- David Morton (6 September 2017). "18 things you probably never knew about Newcastle's magnificent Grey's Monument". ChronicleLive.

- Sarah Chamberlain and Martyn Chamberlain (Spring 2009). "The Legacy of Earl Grey". Durham First. No. 29.

Further reading

- Brett, Peter. "Grey, Charles, 2nd Earl Grey" in D. M. Loades, ed. (2003). Reader's guide to British history. pp. 1:586–87. ISBN 9781579584269.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Smith, E. A. (2004). "Charles Grey, second Earl Grey (1764–1845)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11526. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Smith, E. A. (1990), Lord Grey, 1764–1845, London

- Pennington, D.H."British Prime Ministers : II Earl Grey." History Today (May 1951) 1#5 pp 21-27 online].

- Phillips, John A., and Charles Wetherell. "The Great Reform Act of 1832 and the political modernization of England." American historical review 100.2 (1995): 411–436. in JSTOR

- Trevelyan, G. M. (1920), Lord Grey of the Reform Bill online free

Other sources

- Mosley, Charles (1999), Burke's Peerage and Baronetage of Great Britain and Ireland (106th ed.), Cassells

- A N Other (1910), "A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information", Encyclopædia Britannica, New York, retrieved 10 May 2008

- Mosley, Charles (1999), Charles Mosley (ed.), Burke's Peerage & Baronetage (106th ed.)

- 10 Downing Street website, PMs in history, archived from the original on 25 August 2008, retrieved 26 July 2006

- Temperley, Harold and L.M. Penson, eds. Foundations of British Foreign Policy: From Pitt (1792) to Salisbury (1902) (1938), primary sources online

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey |

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Earl Grey

- Works by or about Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- "Archival material relating to Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Works by or about Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey at Internet Archive

.svg.png.webp)