1968 Borrego Mountain earthquake

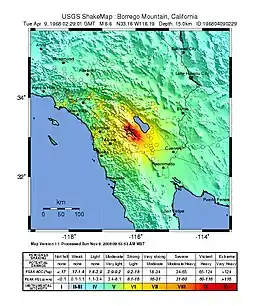

The 1968 Borrego Mountain earthquake occurred in the evening hours of April 8, near the small unincorporated community of Ocotillo Wells in San Diego County. The moment magnitude 6.6 (7.0 on the surface wave magnitude scale) earthquake reached IX (Violent) on the Mercalli intensity scale, causing some damage in the Imperial Valley, although no injuries or deaths had been reported. Shaking from this earthquake was felt over a wide area, even being reported in Las Vegas, Nevada, and parts of Arizona. This was the largest earthquake in Southern California since the 1952 Kern County earthquake 16 years prior.[1]

| |

Las Vegas Los Angeles San Diego Las Vegas | |

| UTC time | 1968-04-09 02:28:58 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 823631 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | April 8, 1968 |

| Local time | 6:29 p.m. PST |

| Magnitude | 6.6 Mw 7.0 Ms |

| Depth | 10.0 km 20.0 km |

| Epicenter | 33.180°N 116.103°W |

| Type | Strike-slip |

| Areas affected | Southern California |

| Total damage | Minor |

| Max. intensity | IX (Violent) |

| Landslides | Yes |

| Casualties | None |

Although the earthquake did not have any major implications to Southern California, it was significant to the scientific community as this earthquake displayed classic afterslip characteristic, and is the first documented earthquake where faults at considerable distances from the event source showed significant movements. A similar instance was seen along the seismically quiet Garlock Fault after the Kern County earthquake, and again after the Ridgecrest earthquake sequence.

Tectonic setting

The Salton Trough is a pull-apart basin that formed as a result of offsets between the numerous strike-slip faults along its edges. It is a component of the much bigger San Andreas Fault System, joining the San Andreas Fault with the Imperial Fault via the Brawley Seismic Zone. The San Andreas Fault is the main plate boundary that defines the margin between the Pacific and North American Plates in California. However, the plate boundary is slightly more complex; rather than a single fault structure that makes up the boundary, the region is straddled and crisscrossed with numerous shorter faults to accommodate the movement of these two plates.

One of these faults is the San Jacinto Fault Zone; a complex, highly segmented, overlapped, 210 km long fault zone that runs east of the Salton Sea, and parallel to the San Andreas Fault.[2] It is separated from the San Andreas Fault by the San Jacinto Mountains to its east. The cuts under cities like Hemet, Colton, and San Bernardino along the way, before joining the San Andreas Fault at Devore. Because the fault is so segmented, some branches have their own individual names, although they are considered part of the system of faults. Considered the most active fault in all of Southern California, it has producing at least eleven earthquakes of Mw 6.0 or greater since the late 19th century. Possibly its most damaging and largest earthquake took place in 1812, where 40 people were killed at Mission San Juan Capistrano when the fault produced an Mw 7.0-7.5. The most recent earthquake was the doublet earthquake of 1987, nearly a month after the Whittier Narrows earthquake. The 1987 pair temblors inflicted heavy damages to Westmorland, and indirectly killed two people outside Mexicali.[3]

Earthquake

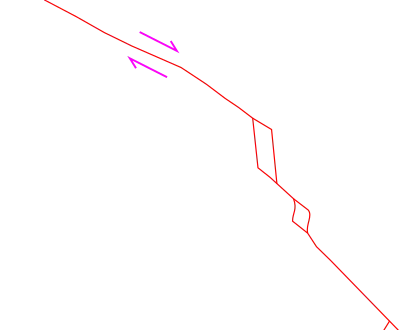

The Mw 6.6 earthquake ruptured a section of the 80 km long Coyote Creek Fault with an almost pure right-lateral (dextral) strike-slip mechanism and is confined to within California, not crossing into Baja California. The 33 km long surface rupture was well expressed due to the lack of vegetation, low precipitation, and flat topography. Two sharp discontinuities in the rupture divide the breakage into three sections (north, central, and south); and smaller, isolated ruptures were found 3 km away from the main trace. The surface ruptures consists of en echelon and parallel breaks rather than one consistent trace.[4] The rupture width ranged from 1 meter to as much as 100 meters across throughout its length. Since the entire rupture did not cross any man-made structures, determining the displacements made by the earthquake was quite difficult. Geologists used channels and tire tracks crossing the fault prior to the earthquake to measure the horizontal shifts instead.[4] However, strong winds blew sand which buried many parts of the rupture and filled in cracks. Additionally, the affected area was visited by many vehicles that crossed and destroyed important evidences to map and determine the lateral movement. A maximum offset of 38 cm was measured at the foothills of Borrego Mountain.[4]

Unusually, left-lateral displacements were discovered 1 to 2 km from Ocotillo Badlands north of California 78 and at the northern base of Borrego Mountain.[4] The fractures at the base of Borrego Mountain had more vertical components in the rupture than there are for the left-lateral. Whether the left-lateral offsets were part of the rupture mechanism or a result of environmental changes, unrelated to tectonic processes could not be confirmed as these displacements were lost in the desert.[4]

Post-earthquake effects

Post-earthquake slips

Even after the earthquake, the fault displayed a phenomenon known as aseismic creeping, observed only along the central and southernmost section of the rupture. The central section was discovered to be creeping several weeks after the earthquake, in June of 1968. The creep increased the total horizontal displacement along the central breakage from 18 cm to 25-30 cm, while vertical displacement increased from 10 cm to 15-23 cm two months after the shock. This was possible documentation of new fractures forming. The new ruptures were discovered on 9 June, 1968 by the manager of a motel at Ocotillo Wells who spotted them on a hill, convinced that they weren't present at the time of the earthquake.[5]

While the central rupture was creeping, there were no signs of movement along the southernmost rupture until January 1969, continuing through into December 1970. There was no feasible way of measuring the offsets made by the creep as tracks; the only evidence for measuring the April 1968 displacements had disappeared. It has been estimated that the post-quake movements have offset the ground by a further 3-6 cm, from the 8 cm that was from the earthquake.

A pair of earthquakes on the Superstition Hills Fault in 1987 would cause the 1968 rupture to creep again for 1.5 cm along a 3 km section.[6]

Triggered slips

The Borrego Mountain earthquake resulted in slippage along nearby major faults including the San Andreas, Imperial Valley, and Superstition Hills Faults. Movement on other faults was first discovered on the Imperial Fault, which prompted checks on other nearby faults. Movements were not detected on other prominent faults such as the San Jacinto Faults north of the Coyote Creek Fault, Superstition Mountains Fault that lies parallel to the Superstition Hills Fault, and the Elsinore Fault Zone.[7]

Imperial Fault

Evidence of movement along the Imperial Fault was discovered four days after the earthquake on Interstate 80 (I-80) where cracks had appeared. The estimated length of creep along this fault is between 22 and 30 km, its true slipped length could not be determined as sand dunes and developments have obstructed any possible rupture trace. The Imperial Fault is believed to have slipped for 0.8 cm during the earthquake. However, the cracks were not well determined as there were already cracks to the road from an earthquake in March of 1966 (the magnitude 3.6 earthquake is the smallest earthquake associated with a surface rupture[8]).[7]

The Imperial Fault would slip again in 1971 six days after a magnitude 5.0 earthquake on the Superstition Hills Fault.[9] About 1.4 cm of prominent horizontal offset was seen on I-80.

Superstition Hills Fault

Two and a half centimeters of displacement was measured at Imler Road, crossing the Superstition Hills Fault, which had moved for 23 km. This fault is part of the San Jacinto Fault Zone, together with the Coyote Creek Fault.[7]

San Andreas Fault

Movement along the Mojave segment of the San Andreas was noted on April 24. This section has not seen any major earthquake since an ~Mw 7.7-7.8 in 1680 and possibly the 1812 earthquakes which happened on December 8 and December 21 respectively.[10] Right-lateral displacement of 1.3 cm was measured, together with many scarps as high as 50 cm. Slippage was traced for about 30 km.[7]

Impact

At the earthquake's epicenter area, the shaking intensity reached VIII to IX on the Mercalli intensity scale, but limited damage was done to the region despite the high intensity. Rockfalls, slumps and liquefaction took place as a result of the violent ground motion.[11] Damage was surprisingly light, and confined to the Imperial Valley for an earthquake of this size. Cracked and fragmented concrete bridge piers were some of the more serious damage associated with the earthquake. Ocotillo Wells, the closest community to the earthquake sustained minimal damage although one house had its walls split apart, and had the bedroom detached from the structure.[11][12] California 78 near the community suffered cracks, and rockslides blocked off the Montezuma-Borrego Highway. Power lines in San Diego County were severed because of the earthquake while plasters fell off buildings in Los Angeles.[1] The shaking also caused the RMS Queen Mary, dry docked at Long Beach to rock for five minutes.[1]

References

- "Borrego Mountain Earthquake". Southern California Earthquake Data Center. Retrieved 13 Dec 2020.

- Dorsey, R.J. "San Jacinto Fault Zone in Southern California". Quaternary to Recent Basin Development and Neotectonics of the Central San Jacinto Fault Zone, Southern California. Retrieved 13 Dec 2020.

- Singer, Eugene. "Geology of California's Imperial Valley". sci.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- Clark, Malcolm M. (1972). "Surface rupture along the Coyote Creek fault". Geological Survey Professional Paper. 787: 55–86. doi:10.3133/pp787.

- Burford, R. O. (1972). "Continued slip on the Coyote Creek fault after the Borrego Mountain earthquake". Geological Survey Professional Paper. 787: 105–111.

- K. W. Hudnut, M. M. Clark (1989). "New slip along parts of the 1968 Coyote Creek fault rupture, California". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 79: 451–465.

- Allen, Clarence R. (1972). "Displacements on the Imperial, Superstition Hills, and San Andreas faults triggered by the Borrego Mountain earthquake". Geological Survey Professional Paper. 787: 87–104.

- JAMES N. BRUNE AND CLARENCE R. ALLEN (June 1967). "A LOW-STRESS-DROP, LOW-MAGNITUDE EARTHQUAKE WITH SURFACE FAULTING: THE IMPERIAL, CALIFORNIA, EARTHQUAKE OF MARCH 4, 1966" (PDF). Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 57: 501–514 – via Caltech.

- "M 5.0 - 18km WSW of Westmorland, CA". USGS-ANSS. Retrieved 13 Dec 2020.

- "CALIFORNIA EARTHQUAKE HISTORY". MySafeLA. Retrieved 13 Dec 2020.

- R. O. Castle and T. L. Youd (1972). "ENGINEERING GEOLOGY". Geological Survey Professional Paper. 787: 158–174.

- Carl W Stover, Jerry L Coffman (1993). "Seismicity of the United States, 1568-1989 (revised)".