1988 Italian Grand Prix

The 1988 Italian Grand Prix was a Formula One motor race held on 11 September 1988 at the Autodromo Nazionale di Monza, Monza. It was the twelfth race of the 1988 season. It is often remembered for the 1–2 finish for the Ferrari team, and as the only race of the 1988 season that McLaren-Honda failed to win.

| 1988 Italian Grand Prix | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Race 12 of 16 in the 1988 Formula One World Championship | |||

| |||

| Race details | |||

| Date | 11 September 1988 | ||

| Official name | LIX Coca-Cola Gran Premio d'Italia | ||

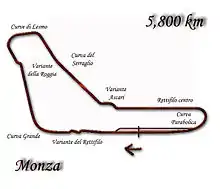

| Location | Autodromo Nazionale di Monza, Monza, Italy | ||

| Course | Permanent racing facility | ||

| Course length | 5.80 km (3.603 mi) | ||

| Distance | 51 laps, 295.800 km (183.801 mi) | ||

| Weather | Sunny and hot | ||

| Pole position | |||

| Driver | McLaren-Honda | ||

| Time | 1:25.974 | ||

| Fastest lap | |||

| Driver |

| Ferrari | |

| Time | 1:29.070 on lap 44 | ||

| Podium | |||

| First | Ferrari | ||

| Second | Ferrari | ||

| Third | Arrows-Megatron | ||

|

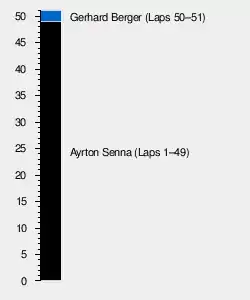

Lap leaders

| |||

Report

Qualifying

Qualifying at Monza went as expected with the McLarens of Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost heading the field, Senna the only driver to lap under 1:26. In the first Italian Grand Prix since the death of Ferrari founder Enzo Ferrari, his team's scarlet cars were 3rd and 4th on the grid, Gerhard Berger in front of Michele Alboreto. As a mark of respect for the Ferrari founder, Alboreto and Berger were allowed to be the first cars to take to the track for Friday morning's first practice session.

Showing the difference in horsepower between 1987 and 1988, Senna's pole time of 1:25.974 was 2.514 seconds slower than Nelson Piquet's 1987 time of 1:23.460. For the most part, qualifying times in 1988 had either matched or actually beaten the times from the previous year showing advances in engine response, aerodynamics, tyres and suspension. However, on a power circuit such as Monza, the loss of some 300 bhp (224 kW; 304 PS) was very noticeable.

The third row of the grid was a surprise, even at this power circuit. Ever since the item was made compulsory for turbo powered cars at the start of the 1987 season, the Arrows team had been experiencing problems with the FIA pop-off valve on their Megatron turbo engines, the problem being that the valve was cutting in too early and the drivers weren't able to exploit the full available power. In 1987 this meant that drivers Derek Warwick and Eddie Cheever struggled to keep up with their turbocharged rivals. In 1988 it meant they were often only as fast as the leading atmos, and often they were in fact slower, even on noted power circuits such as Silverstone and Hockenheim which should have suited their turbo power. The team's engine guru Heini Mader had finally solved the pop-off valve problem (which turned out to be the pop-off valve being located too high above the engine, a problem Honda and Ferrari had long since solved), and suddenly with an extra 30-50 bhp at their disposal the Arrows A10B's were actually 5 km/h (3 mph) faster than the Honda-powered McLarens across the start line and by the time they reached the speed trap before the Rettifilo, Cheever was reported to be the only car to hit 200 mph (322 km/h) while the McLarens and Ferraris were timed at around 192 mph (309 km/h). This new found power allowed Cheever and Warwick to line up 5th and 6th respectively, one place in front of World Champion Nelson Piquet in his Lotus Honda. This also meant that turbos filled the first seven places on the grid.[1] Piquet's Lotus teammate Satoru Nakajima qualified 10th, with the Lotuses split by the fastest non-turbos, the Benetton-Fords of Thierry Boutsen and Alessandro Nannini in 8th and 9th places on the grid.

Defending World Champion Piquet, the race winner in 1986 and 1987 when driving for Williams, never looked at ease during qualifying at a track where the Honda powered Lotus 100T should have been a long way ahead of at least the 'atmo' cars. Only late on in qualifying was it discovered that the team had inadvertently set up both Piquet and Nakajima's cars with the settings for the Imola circuit and not for Monza.[2]

The 1988 Italian Grand Prix was the last race of the first turbo era in Formula One in which all cars powered by turbocharged engines that entered actually qualified for the race. The McLarens, Ferraris, Arrows, Lotuses, Zakspeeds and the single Osella of Nicola Larini all qualified at least 17th, Larini's car being the slowest, some 4.5 seconds behind Senna.

Race

With emotions running high so soon after the death of Enzo Ferrari, the tifosi had been praying for a Ferrari victory at Monza. However, with McLaren having won all 11 races of the 1988 season up to this point, hopes for a home victory seemed bleak.

Nigel Mansell was still affected by chicken pox, and was still forced to sit out. Martin Brundle, his replacement in Belgium, was asked to race again but his Jaguar Sportscar team boss Tom Walkinshaw vetoed the move, so the second Williams seat went to team test driver (and Brundle's chief rival for the 1988 World Sportscar Championship) Jean-Louis Schlesser.

Prost managed to jump Senna at the start, but as he changed from 2nd to 3rd on the run to the Rettifilo his engine began to misfire and would not run properly again. This allowed Senna to power past into the lead before the chicane. Berger followed Prost with Alboreto, Cheever, Boutsen, Patrese and Piquet running in line. Senna built up a 2-second lead after the first lap and Prost, realising after the first lap that the misfire was not going away, decided to turn his boost up to full and give chase to his teammate.

Berger had initially given chase and stayed within a couple of seconds of Prost, but before lap 10 had started to drop back in order to save fuel. By lap 30 the Frenchman had reduced Senna's lead to only 2 seconds, but as he went by the pits at the end of lap 30 the misfire suddenly got worse and by lap 35 had been passed by Berger and Alboreto and was heading for the pits and his first mechanical retirement of the season (and the only time in 1988 that a McLaren would retire due to engine failure). While this was happening Alboreto, troubled by gear selection problems early in the race, had dropped back from Berger to allow his gearbox oil to cool hoping it would come good. It did and the Italian in the All-Italian car began to charge at the Italian Grand Prix, and was catching his teammate.

Later in the race Berger and Alboreto began closing on Senna rapidly, though it was assumed that Senna was merely pacing himself to the finish, and Senna himself later said that he had things well in hand. With two laps remaining, Senna attempted to lap the Williams of Schlesser at the Rettifilo. Senna headed to the left to pass the Frenchman on the inside of the first chicane, but Schlesser locked his brakes and the Williams slid forward towards the gravel trap. Using his rallying skills, Schlesser managed to collect the car and turned left to avoid going off. Senna, who had taken his normal line and had not counted on Schlesser regaining control, was struck in the right rear by the Williams, breaking the McLaren's rear suspension and causing the car to spin and beach itself on a kerb, putting the Brazilian out of the race. BBC commentator James Hunt placed the blame squarely on Schlesser, although many felt that Senna had not given any allowance for Schlesser to come back on the track. Senna's compatriot and close friend Maurício Gugelmin, whose March-Judd had also been about to lap Schlesser and was behind the McLaren after being lapped on the run past the pits, saw the collision in its entirety. "I think he'd felt that Schlesser would go straight off, and in that situation you have to keep going. It's a difficult situation, but I don't think Ayrton took a risk."[3]

It was generally thought that Senna had used too much fuel in the first half of the race in his bid to keep in front of Prost and that was why the Ferraris were rapidly catching him towards the end of the race, with Berger reducing what was a 26-second gap when Prost retired, to be only 5 seconds behind when Senna and Schlesser collided 14 laps later. Senna's former Lotus team boss Peter Warr commented after the race that he felt Prost, knowing he wouldn't finish the race, had suckered his teammate into using too much fuel in the hope that it would keep his championship hopes alive. He also added that if Senna had thought about it he'd have realised that to stay close to him, Prost must have also been using too much fuel and that was not something the dual World Champion usually did. Prost's tactics may have contributed to McLaren missing out on a perfect season, but they had the desired effect as Senna scored no points (after four straight wins including Britain where Prost failed to finish) and he was still in with a good chance of winning his third World Championship.

The Tifosi were beyond overjoyed as Berger inherited the win, with Alboreto taking second place only half a second behind in the first Italian Grand Prix since the death of the great Enzo Ferrari. Alboreto was actually the fastest driver on the track in the last laps and gained over 4 seconds on his teammate in the final 3 laps. American Eddie Cheever (who actually grew up in Rome) finished in 3rd place for Arrows, 35 seconds behind the Ferraris and only half a second in front of his teammate Derek Warwick in a great race for the Arrows team. Warwick had actually got a bad start and had fallen outside of the top ten. However, with the Megatron engine now producing full power the Englishman began to charge and ran the last 10 laps challenging his teammate. The remaining points went to Italian Ivan Capelli, a considerable achievement by the atmospheric March-Judd on a circuit which requires powerful engines (Capelli spent the first half of the race locked in a battle for 6th place with the Williams of Riccardo Patrese and Warwick's Arrows). Capelli's high place also showed just how aerodynamic the Adrian Newey designed March 881 was. Sixth place went to the Benetton-Ford of Thierry Boutsen.

Motor racing journalist Nigel Roebuck later reported that after the race an overjoyed member of the Tifosi had approached Schlesser, shook his hand and said "Thank you, from Italy".

Another hard luck story was Alessandro Nannini who was forced to start his home Grand Prix from the pits due to a failed throttle on the warm up lap. By the time the Benetton team fixed the problem, Senna was coming through the Parabolica on his first lap meaning the Italian, who was to start 9th, was last and almost a lap down within the first lap of the race. For the rest of the afternoon Nannini charged, setting the fastest lap of the race for atmospheric cars and finishing in 9th place.

Post-race scrutineering

In the scrutineering bay, Berger's Ferrari's fuel capacity was checked four times. The first time, FISA officials were able to refill the tank with 151.5 litres of fuel, exceeding the limit of 150 litres. A second refill and then a third were undertaken, and still the Ferrari took too much. Eventually they succeeded in adding just 149.5 litres at the fourth time of asking.[3] Eddie Cheever's Arrows had the same problem as Berger's Ferrari when his fuel tank was at first found to be 151 litres, but further checking found it to be under the limit at 149.5 litres.

Classification

Pre-Qualifying

| Pos | No | Driver | Constructor | Time | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | Dallara-Ford | 1:30.877 | — | |

| 2 | 31 | Coloni-Ford | 1:32.860 | +1.983 | |

| 3 | 33 | EuroBrun-Ford | 1:33.292 | +2.415 | |

| 4 | 21 | Osella | 1:33.738 | +2.861 | |

| DNPQ | 32 | EuroBrun-Ford | 1:34.044 | +3.167 |

Qualifying

| Pos | No | Driver | Constructor | Q1 | Q2 | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | McLaren-Honda | 1:26.160 | 1:25.974 | — | |

| 2 | 11 | McLaren-Honda | 1:26.277 | 1:26.428 | +0.303 | |

| 3 | 28 | Ferrari | 1:28.082 | 1:26.654 | +0.680 | |

| 4 | 27 | Ferrari | 1:27.618 | 1:26.988 | +1.014 | |

| 5 | 18 | Arrows-Megatron | 1:28.101 | 1:27.660 | +1.686 | |

| 6 | 17 | Arrows-Megatron | 1:28.258 | 1:27.815 | +1.841 | |

| 7 | 1 | Lotus-Honda | 1:28.440 | 1:28.044 | +2.070 | |

| 8 | 20 | Benetton-Ford | 1:29.607 | 1:28.870 | +2.896 | |

| 9 | 19 | Benetton-Ford | 1:28.969 | 1:28.958 | +2.984 | |

| 10 | 6 | Williams-Judd | 1:30.124 | 1:29.435 | +3.461 | |

| 11 | 16 | March-Judd | 1:29.513 | 1:29.696 | +3.539 | |

| 12 | 2 | Lotus-Honda | 1:29.541 | 1:30.570 | +3.567 | |

| 13 | 15 | March-Judd | 1:30.145 | 1:30.035 | +4.061 | |

| 14 | 23 | Minardi-Ford | 1:30.734 | 1:30.125 | +4.151 | |

| 15 | 10 | Zakspeed | 1:30.773 | 1:30.161 | +4.187 | |

| 16 | 9 | Zakspeed | 1:31.182 | 1:30.035 | +4.061 | |

| 17 | 21 | Osella | 1:31.721 | 1:30.481 | +4.507 | |

| 18 | 22 | Rial-Ford | 1:31.263 | 1:30.560 | +4.586 | |

| 19 | 24 | Minardi-Ford | 1:30.944 | 1:30.698 | +4.724 | |

| 20 | 30 | Lola-Ford | 1:31.168 | 1:30.962 | +4.988 | |

| 21 | 36 | Dallara-Ford | 1:30.989 | 1:31.009 | +5.015 | |

| 22 | 5 | Williams-Judd | 1:31.548 | 1:31.620 | +5.574 | |

| 23 | 14 | AGS-Ford | 1:31.676 | 1:31.687 | +5.702 | |

| 24 | 25 | Ligier-Judd | 1:32.049 | 1:32.316 | +6.075 | |

| 25 | 29 | Lola-Ford | 1:32.164 | 1:32.686 | +6.190 | |

| 26 | 4 | Tyrrell-Ford | 1:32.573 | 1:32.290 | +6.316 | |

| DNQ | 3 | Tyrrell-Ford | 1:32.405 | 1:33.067 | +6.431 | |

| DNQ | 26 | Ligier-Judd | 1:33.272 | 1:32.438 | +6.464 | |

| DNQ | 31 | Coloni-Ford | 1:32.829 | 1:35.805 | +6.855 | |

| DNQ | 33 | EuroBrun-Ford | 1:34.727 | 1:33.226 | +7.252 |

Race

Notes

- Until the 2014 season, when turbocharged engines were re-introduced, this was the last Formula One race in which all turbo-powered cars that were entered actually qualified for the race.

Championship standings after the race

- Bold text indicates the World Champions.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Note: Only the top five positions are included for both sets of standings. Points accurate at final declaration of results. The Benettons were subsequently disqualified from the Belgian Grand Prix and their points reallocated.

References

- "Arrows A10B". Gurney Flap. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- F1 1988 FIA Review - 12 Italy.flv. 21 December 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2016 – via YouTube.

- David Tremayne (3 September 2013). "RETRO: Miracle at Monza". Racer.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- "1988 Italian Grand Prix". formula1.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- "Italy 1988 - Championship • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

| Previous race: 1988 Belgian Grand Prix |

FIA Formula One World Championship 1988 season |

Next race: 1988 Portuguese Grand Prix |

| Previous race: 1987 Italian Grand Prix |

Italian Grand Prix | Next race: 1989 Italian Grand Prix |