Autodromo Nazionale di Monza

The Autodromo Nazionale di Monza is a historic race track near the city of Monza, north of Milan, in Italy. Built in 1922, it is the world's third purpose-built motor racing circuit after those of Brooklands and Indianapolis.[5] The circuit's biggest event is the Italian Grand Prix. With the exception of the 1980 running, the race has been hosted there since 1949.[6]

| |

| Location | Monza, Italy[1] |

|---|---|

| Time zone | GMT +1 |

| Coordinates | 45°37′14″N 9°17′22″E |

| Capacity | 118,865[2] |

| FIA Grade | 1 |

| Owner | Comune di Monza & Milano[1] |

| Operator | SIAS S.p.A.[1] |

| Broke ground | 15 May 1922 |

| Opened | 3 September 1922 |

| Architect | Alfredo Rosselli |

| Major events | Formula One Italian Grand Prix Italian motorcycle Grand Prix, 1000 km Monza, SBK, Race of Two Worlds |

| Modern Grand Prix Circuit | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 5.793[3][4] km (3.600 mi) |

| Turns | 11 |

| Race lap record | 1:21.046 ( |

| Oval | |

| Surface | Concrete/Asphalt |

| Length | 4.250[4] km (2.641 mi) |

| Turns | 2 |

| Banking | ≈30° |

| Race lap record | 0:54.0 ( |

| Junior Course | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 2.405[4] km (1.494 mi) |

| Combined Course | |

| Surface | Asphalt/Concrete |

| Length | 10.00 km (6.213 mi) |

| Turns | 9 |

| Race lap record | 2.41.4 ( |

| Website | www |

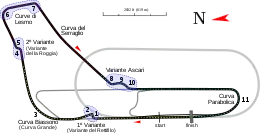

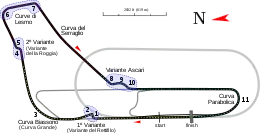

Built in the Royal Villa of Monza park in a woodland setting,[7] the site has three tracks – the 5.793-kilometre (3.600 mi) Grand Prix track,[3] the 2.405-kilometre (1.494 mi) Junior track,[4] and a 4.250-kilometre (2.641 mi) high speed oval track with steep bankings which was left unused for decades and had been decaying until it was restored in the 2010s.[8][6] The major features of the main Grand Prix track include the Curva Grande, the Curva di Lesmo, the Variante Ascari and the Curva Parabolica. The high speed curve, Curva Grande, is located after the Variante del Rettifilo which is located at the end of the front straight or Rettifilo Tribune, and is usually taken flat out by Formula One cars.

Drivers are on full throttle for most of the lap due to its long straights and fast corners, and is usually the scenario in which the open-wheeled Formula One cars show the raw speed of which they are capable: 372 kilometres per hour (231 mph) during the mid-2000s V10 engine formula, although in 2012 with the 2.4L V8 engines, top speeds in Formula One rarely reached over 340 kilometres per hour (211 mph); the 1.6L turbocharged hybrid V6 engine, reduced-downforce formula of 2014 displayed top speeds of up to 360 kilometres per hour (224 mph). The circuit is generally flat, but has a gradual gradient from the second Lesmos to the Variante Ascari. Due to the low aerodynamic profile needed, with its resulting low downforce,[9] the grip is very low; understeer is a more serious issue than at other circuits; however, the opposite effect, oversteer, is also present in the second sector, requiring the use of a very distinctive opposite lock technique. Since both maximum power and minimal drag are keys for speed on the straights, only competitors with enough power or aerodynamic efficiency at their disposal are able to challenge for the top places.[9]

In addition to Formula One, the circuit previously hosted the 1000 km Monza, an endurance sports car race held as part of the World Sportscar Championship and the Le Mans Series. Monza also featured the unique Race of Two Worlds events, which attempted to run Formula One and USAC National Championship cars against each other. The racetrack also previously held rounds of the Grand Prix motorcycle racing (Italian motorcycle Grand Prix), WTCC, TCR International Series, Superbike World Championship, Formula Renault 3.5 Series and Auto GP. Monza currently hosts rounds of the Blancpain GT Series Endurance Cup, International GT Open and Euroformula Open Championship, as well as various local championships such as the TCR Italian Series, Italian GT Championship, Porsche Carrera Cup Italia and Italian F4 Championship, as well as the Monza Rally Show. In 2020 Monza hosted the 2020 World Rally Championship final round, ACI Rally Monza, with the circuit hosting 10 of the 16 rally stages.

Monza also hosts cycling and running events, most notably the Monza 12h Cycling Marathon[10] and Monza 21 Half Marathon.[10] The venue was also selected by Nike scientists for the Breaking2 event, where three runners attempted to break the 2 hour barrier for the marathon. Eliud Kipchoge ran 2:00:25.[11]

The Monza circuit has been the site of many fatal accidents, especially in the early years of the Formula One world championship,[9] and has claimed the lives of 52 drivers and 35 spectators. Track modifications have continuously occurred, to improve spectator safety and reduce curve speeds,[6] but it is still criticised by the current drivers for its lack of run-off areas, most notoriously at the chicane that cuts the Variante della Roggia.[9]

History

Early history

The first track was built from May to July 1922 by 3,500 workers, financed by the Milan Automobile Club[7] – which created the Società Incremento Automobilismo e Sport (SIAS) (English: Motoring and Sport Encouragement Company) to run the track.[12] The initial form was a 3.4 square kilometres (1.31 sq mi) site with 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) of macadamised road – comprising a 4.5 kilometres (2.80 mi) loop track, and a 5.5 kilometres (3.42 mi) road track.[7][12] The track was officially opened on 3 September 1922, with the maiden race the second Italian Grand Prix held on 10 September 1922.[12]

In 1928, the most serious Italian racing accident to date[7][9] ended in the death of driver Emilio Materassi and 27 spectators at that year's Italian Grand Prix.[7][9] The accident led to further Grand Prix races confinement to the high-speed loop until 1932.[13] For these reasons the Italian Grand Prix wasn't held again until 1931; in the meantime the 1930 Monza Grand Prix was held on the high speed ring only, while in 1930 Vincenzo Florio introduced the Florio Circuit. The 1933 Italian Grand Prix was held on the original complete layout but it was marred by the deaths of three drivers (Giuseppe Campari, Baconin Borzacchini and Stanislaw Czaykowski) in the supporting Monza Grand Prix held on the same day - which became known as the "Black Day of Monza" - over the shorter oval circuit [12][14] [15]and the Grand Prix layout was changed: in 1934 a short circuit with two lanes of the straight line joined by a hairpin, Curva Sud of the banking (with a double chicane) driven in the opposite direction than usual, the "Florio link" and the Curva Sud (with a small chicane). This configuration was considered too slow and in 1935 Florio Circuit was used again, this time with four temporary chicanes and another one permanent (along the Curva Sud of the banking). In 1938 only the last one was used.[16]

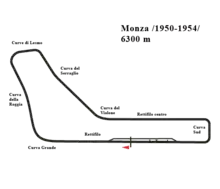

There was major rebuilding in 1938–39, constructing new stands and entrances, resurfacing the track, removing the high speed ring and adding two new bends on the southern part of the circuit.[12][13] The resulting layout gave a Grand Prix lap of 6.300 kilometres (3.91 mi), in use until 1954.[17] The outbreak of World War II meant racing at the track was suspended until 1948[17] and parts of the circuit degraded due to the lack of maintenance and military use.[6] Monza was renovated over a period of two months at the beginning of 1948[12] and a Grand Prix was held on 17 October 1948.[17]

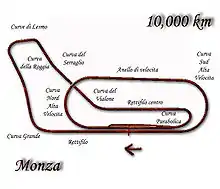

High speed oval

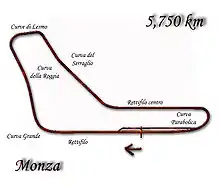

In 1954, work began to entirely revamp the circuit, resulting in a 5.750 kilometres (3.573 mi) course, and a new 4.250 kilometres (2.641 mi) high-speed oval with banked sopraelevata curves (the southern one was moved slightly north).[6][18] The two circuits could be combined to re-create the former 10 kilometres (6.214 mi)[6] long circuit, with cars running parallel on the main straight. The first Lesmo curve was modified to be made faster, and the track infrastructure and facilities were also updated and improved to better accommodate the teams and spectators.[12][18]

The Automobile Club of Italy held 500-mile (805 km) Race of Two Worlds exhibition competitions, intended to pit United States Auto Club IndyCars against European Formula One and sports cars.[6][18] The races were held on the oval at the end of June in 1957 and 1958,[19] with three 63 lap[20] 267.67 kilometres (166.32 mi) heat races each year, races which colloquially became known as the Monzanapolis series.[19][21] Concerns were raised among the European drivers that flat-out racing on the banking would be too dangerous,[21] so ultimately only Ecurie Ecosse and Maserati represented European racing at the first running.[22] The American teams had brought special Firestone tyres with them, reinforced to withstand high-speed running on the bumpy Monza surface, but the Maseratis' steering was badly affected by the larger-than-usual tyre size, leading to the Modena-based team withdrawal.[22]

Ecurie Ecosse's three Jaguar D-type sports cars used their Le Mans-specification tyres with no ill-effects, but since they raced at less than their practice speeds to conserve their tyres, they were completely out paced. Two heats in 1957 were won by Jimmy Bryan in his Kuzma-Offenhauser Dean Van Lines Special,[22][23] and the last by Troy Ruttman in the Watson-Offenhauser John Zink Special.[24] In 1958 Jaguar, Ferrari and Maserati teams appeared alongside the Indy roadsters,[18][25] but once again the American cars dominated the event and Jim Rathmann won the three races in a Watson-Offenhauser car.[19]

Formula One used the 10 kilometres (6.214 mi) high speed track in the 1955, 1956, 1960 and 1961 Grands Prix.[6][18] Stirling Moss and Phil Hill both won twice in this period, with Hill's win at Monza making him the first American to win a Formula One race.[26] The 1961 race saw the death of Wolfgang von Trips and fifteen spectators when a collision with Jim Clark's Lotus sent von Trips' car airborne and into the barriers on Parabolica.[12][26]

Although the accident did not occur on the oval section of the track, the high speeds were deemed unsafe and F1 use of the oval was ended;[27] future Grands Prix were held on the shorter road circuit,[18] with the banking appearing one last time in the film Grand Prix.[27] New safety walls, rails and fences were added before the next race and the refuelling area was moved further from the track. Chicanes were added before both bankings in 1966, and another fatality in the 1968 1000 km Monza race led to run-off areas added to the curves, with the track layout changing the next year to incorporate permanent chicanes before the banked curves – extending the track length by 100 metres (328 ft).[18]

The banking held the last race in 1969 with the 1000 km of Monza, the event moving to the road circuit the next year.[18] The banking still exists, albeit in a decayed state in the years since the last race, escaping demolition in the 1990s. It is used once a year for the Monza Rally.[27] The banked oval was used several times for record breaking until the late 1960s, although the severe bumping was a major suspension and tyre test for the production cars attempting endurance records, such as the Ford Corsair GT which in 1964 captured 13 records.[28]

Circuit changes and modernisation

Both car and Grand Prix motorcycle racing were regular attractions at Monza.[18] These races involved drivers constantly slipstreaming competing cars, which produced several close finishes, such as in 1967, 1969, and 1971.

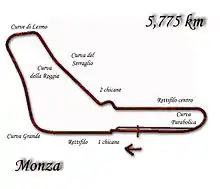

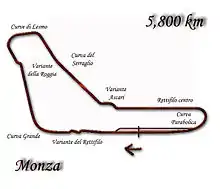

As the speed of the machines increased, two chicanes were added in 1972 to reduce racing speeds — the Variante del Rettifilo at the middle of the start/finish straight,[29] and the Variante Ascari.[12] This resulted in a new circuit length of 5.755 kilometres (3.576 mi).[29] Grand Prix motorcycles continued to use the un-slowed road track until two serious accidents resulted in five deaths, including Renzo Pasolini and Jarno Saarinen,[29] in 1973, and motorcycle racing did not return to Monza until 1981.[29] The 1972 chicanes were soon seen to be ineffective at slowing cars; the Vialone was remade in 1974,[29] the other, Curva Grande in 1976,[12] and a third also added in 1976 before the Lesmo, with extended run-off areas.[29] The Grand Prix lap after these alterations was increased to 5.800 kilometres (3.604 mi) long.[29]

With technology still increasing vehicle speeds the track was modified again in 1979 with added safety measures such as new kerbs, extended run-off areas and tyre-barriers to improve safety for drivers off the track.[30] The infrastructure was also improved, with pits able to accommodate 46 cars, and an upgraded paddock and scrutineering facilities.[30] These changes encouraged world championship motorcycling to return in 1981, but further safety work was undertaken through the 1980s.[30] Also in the 1980s the podium, paddock and pits complex, stands,[30][31] and camp site were either rebuilt or improved.[12]

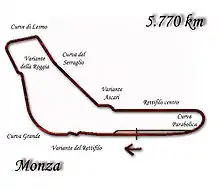

As motorsport became more safety conscious following the deaths of Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger in 1994 at the Imola circuit, the three main long curves were "squeezed" in order to install larger gravel traps, shortening the lap to 5.770 kilometres (3.585 mi).[31] In 1997 the stands were reworked to expand capacity to 51,000.[31] In 2000, the chicane on the main straight was altered, changing from a double left-right chicane to a single right-left chicane in an attempt to reduce the frequent accidents at the starts due to the conformation of the braking area, although it is still deemed unsafe in terms of motorcycle racing. The second chicane was also re-profiled. In the Formula 1 Grand Prix of the same year, the first to use these new chicanes, a fire marshal, Paolo Gislimberti, was killed by flying debris after a big pileup at the second chicane.[9]

In 2007, the run-off area at the second chicane was changed from gravel to asphalt. The length of the track in its current configuration is 5.793 kilometres (3.600 mi).[3] At the 2010 Monza Superbike World Championship round, Italian rider Max Biaggi set the fastest ever motorcycle lap of Monza when he rode his Aprilia RSV4 1000 F to pole position in a time of 1:42.121. In the Superpole qualification for the 2011 race, he improved on this lap time, for a new lap record of 1:41.745 and his speed was captured at 205+ MPH.

In late 2016, work was planned on a new first bend, which would have bypassed the first chicane and the Curva Grande. Drivers were to go through a fast right hand kink entering the old Pirelli circuit and into a new, faster chicane. Work was planned for to be completed by 2017 in hopes of a renewed contract for Formula 1. Gravel would have also returned to the run-off area at the Parabolica bend.[32] However, plans for the track's change were suspended due to the track being in the historic Monza Park.

A lap of the circuit in a Formula One car

.jpg.webp)

Monza, throughout its long and storied history has been known for its high-speed, simplistic nature thanks to its 1920's design and the few alterations it has received, and is currently the fastest track on the Formula One calendar and has been so since 1991. Monza consists of very long straights and tight chicanes, putting a premium on good braking stability and traction. The 5.793 kilometres (3.600 mi)[3] circuit is very hard on engines- Formula 1 engines are at full throttle for nearly 80% of the lap, with engine failures common, notably Fernando Alonso in the 2006 Italian Grand Prix.

Formula One cars are set up with one of the smallest wing angles on the F1 calendar to ensure the lowest level of drag on the straights. There are only 6 corner complexes at Monza: the first two chicanes, the two Lesmos, the Ascari complex and the Parabolica. Thus cars are set up for maximum performance on the straights.

Cars approach the first corner at 340 kilometres per hour (210 mph) in eighth gear,[3] and brake at about 120 metres (390 ft) before the first chicane – the Variante del Rettifilo – entering at 86 km/h (53 mph) in first gear, and exiting at 74 kilometres per hour (46 mph) in second gear.[3] This is the scene of many first lap accidents. Higher kerbs were installed at the first two chicanes in 2009 to prevent cutting.[34]

Good traction out of the first corner is imperative for a quick lap. Conservation of speed through the first chicane is made possible by driving the straightest line, as a small mistake here can result in a lot of time being lost through the Curva Grande down to the Variante della Roggia chicane in seventh gear, at 330 kilometres per hour (210 mph).[3] The braking point is just under the bridge. The kerbs are very vicious and it is very easy for a car to become unbalanced and a driver to lose control, as Kimi Räikkönen did in 2005. This chicane is probably the best overtaking chance on the lap, as it is the only one with the "slow corner, long straight, slow corner"; one of the characteristics of modern circuits.

The Curve di Lesmo are two corners that are not as fast as they used to be, but are still challenging corners. The first is blind, entered at 264 km/h (164 mph) in fifth gear, dropping to fourth gear at 193 km/h (120 mph),[3] and has a slight banking. The second is a fifth gear entry at 260 km/h (160 mph), apexing in third gear at 178 kilometres per hour (111 mph),[3] and it is very important that all the kerb is used. A mistake at one of these corners will result in a spin into the gravel, while good exits can set you up for an overtaking move into Variante Ascari.

The downhill straight down to Variante Ascari is very bumpy under the bridge. Variante Ascari is a very tricky sequence of corners and is key to the lap time.

The final challenge is the Curva Parabolica: approaching at 335 kilometres per hour (208 mph) in seventh gear,[3] cars quickly dance around the corner, apexing in fourth gear at 215 kilometres per hour (134 mph)[3] and exiting in fifth gear at 285 kilometres per hour (177 mph),[3] accelerating onto the main start/finish straight. A good exit and slipstream off a fellow driver along the main straight can produce an overtaking opportunity under heavy braking into Variante del Rettifilo; however, it is difficult to follow a leading car closely through the Parabolica as the tow will reduce downforce and cornering speed.

Maximum speed achieved in a 2020 Formula One car is 360.8 km/h (224.2 mph), established at the end of the start/finish straight.[35] They experience a maximum g-force of 4.50 during deceleration, as the track has many dramatic high to low speed transitions.[36][3]

Lewis Hamilton recorded the fastest pole position lap at Monza in 2020, when he lapped in 1:18.887 at an average speed of 264.362 km/h (164.267 mph) – the fastest average lap speed recorded in qualifying for a World Championship event.[37][38]

Deaths from crashes

- 1922 Fritz Kuhn (Austro-Daimler), killed during practice for the 1922 Italian Grand Prix[14]

- 1923 Enrico Giaccone, riding as passenger in a Fiat 805 during private testing, with Pietro Bordino driving[14]

- 1923 Ugo Sivocci (Alfa Romeo P1), killed during practice for the 1923 Italian Grand Prix[14]

- 1924 Count Louis Zborowski (Mercedes), killed after crashing into a tree at Lesmo during the 1924 Italian Grand Prix[14]

- 1928 Emilio Materassi and 27 spectators killed after Materassi crashed his Talbot into the grandstand during the 1928 Italian Grand Prix[7][9][14]

- 1931 Luigi Arcangeli (Alfa Romeo), killed after crashing at Lesmo during practice for the 1931 Italian Grand Prix[14]

- 1933 Giuseppe Campari (Alfa Romeo Tipo B 2.6 litre), Mario Umberto Borzacchini (Maserati 8C-3000) and Stanislas Czaykowski (Bugatti), killed after crashing at the south banking during the 1933 Monza Grand Prix[13][14]

- 1954 Rupert Hollaus, killed during practice during the Italian motorcycle Grand Prix

- 1955 Alberto Ascari, killed during private testing at the Vialone, which is now the Ascari chicane, driving a Ferrari 750 Monza, just four days after his harbour crash in the 1955 Monaco Grand Prix[9]

- 1961 Wolfgang von Trips[9][18] and 14 spectators killed after von Trips collided with Jim Clark approaching the Parabolica on the second lap of the 1961 Italian Grand Prix

- 1965 Bruno Deserti, killed during Ferrari official test prior to Le Mans in a Ferrari P2/3 4000 cc

- 1965 Tommy Spychiger, killed during 1000K Sports car race in Ferrari 365P2[18]

- 1970 Jochen Rindt, killed after crashing at the Parabolica during practice for the 1970 Italian Grand Prix[9]

- 1973 Renzo Pasolini, Jarno Saarinen killed in a mass crash at the Curva Grande during the 250 cc class of the Nations Grand Prix (Prior to 1990, the Italian round was called the Nations Grand Prix)[29]

- 1973 Carlo Chionio, Renzo Colombini and Renato Galtrucco during a race for 500 cc Juniores Italian motorcycle championship[29]

- 1974 Silvio Moser, died in hospital one month after suffering injuries at the 1000 km Monza race

- 1978 Ronnie Peterson, died in hospital after crashing during the start of the 1978 Italian Grand Prix[9][12][29]

- 1998 Michael Paquay, Belgian motorbike racer, died after a crash in practice for the Italian round of World Supersport Championships, Honda CBR 600

- 2000 Paolo Gislimberti, a marshal hit by debris from a first-lap accident at the Roggia chicane during the Italian Grand Prix[9][39]

Previous track configurations

Original circuit (1922–1933)

Original circuit (1922–1933) Florio circuit (1935–1937)

Florio circuit (1935–1937) 2nd variation (1950–1954)

2nd variation (1950–1954) 3rd variation (Combined circuit) (1955–1956, 1960–1961)

3rd variation (Combined circuit) (1955–1956, 1960–1961) 4th variation (Road circuit) (1957–1959, 1962–1971)

4th variation (Road circuit) (1957–1959, 1962–1971) 5th variation (1972–1973)

5th variation (1972–1973) 6th variation (1974–1975)

6th variation (1974–1975) 7th variation (1976–1994)

7th variation (1976–1994) 8th variation (1995–1999)

8th variation (1995–1999) 9th variation (2000–present)

9th variation (2000–present)

Events

- Current

- April: Italian GT Championship, TCR Italian Series

- April: Blancpain GT Series Endurance Cup, Formula Renault Eurocup

- May: European Le Mans Series, Michelin Le Mans Cup

- June: Campionato Italiano Auto Storiche

- September: Formula One Italian Grand Prix

- October: Italian GT Championship, TCR Italian Series, Formula Regional European Championship

- October: International GT Open, Euroformula Open Championship, TCR Europe Series

- Former

- Race of Two Worlds

- 1000 km Monza

- FIA GT Championship

- Italian motorcycle Grand Prix

- Superbike World Championship

- Superleague Formula

- World Series by Renault

- World Touring Car Championship

- Special

References

- "Autodromo Nazionale Monza – Company profile". Autodromo Nazionale Monza. MonzaNet.it. 2007. Archived from the original on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "Formula 1 Gran Premio Heineken d'Italia 2020 – Media Kit" (PDF). Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- "Formula 1 Gran Premio Santander D'Italia 2009 (Monza) – interactive circuit map". Formula One Administration Ltd. Formula1.com. 1999–2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "Autodromo Nazionale Monza – Areas & Structures". Autodromo Nazionale Monza. MonzaNet.it. 2007. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "History". Autodromo Nazionale Monza. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016.

- "The hidden history of the Monza banking". Formula One Administration Ltd. Formula1.com. 30 August 2005. Archived from the original on 2 October 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "1922–1928: Construction and first races on the original tracks". Autodromo Nazionale Monza. MonzaNet.it. 2007. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "Monza Oval - History of the abandoned banking". Circuits of the past. 27 August 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- "Fórmula 1: los pilotos tienen miedo por la seguridad en Monza" [Formula 1: the drivers are afraid for safety at Monza] (in Spanish). Clairín.com. 5 September 2006. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "FollowYourPassion". FollowYourPassion.

- Jon Mulkeen (6 May 2017). "Kipchoge a 'happy man' in Monza". IAAF. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- "Autodromo Nazionale di Monza – History". The Formula One DataBase. F1db.com. 6 April 2005. Archived from the original on 2 October 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "1929–1939: In consequence of the Materassi's accident, races are run on the alternative tracks". Autodromo Nazionale Monza. MonzaNet.it. 2007. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "8W – When? – 1933 Monza GP, "Black Sunday"". Forix.autosport.com. May 2001. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- Etzrodt, Hans. "The Black Day of Monza. Campari, Borzacchini and Czaykowski crashed fatally". The Golden Era of Grand Prix Racing.

- "TRACKS - ITALY". www.kolumbus.fi. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "1940–1954: After the war interruption, the activity starts again in 1948". Autodromo Nazionale Monza. MonzaNet.it. 2007. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "1955–1971: Construction of the high speed track and other important works". Autodromo Nazionale Monza. MonzaNet.it. 2007. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "Autodromo Nazionale di Monza". ChampCarStats.com. 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "1958 500 Miglia di Monza Heat 1". ChampCarStats.com. 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "History of Monza GP". About Milan. Archived from the original on 12 October 2010. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- "1957 500 Miglia di Monza Heat 1". ChampCarStats.com. 2009. Archived from the original on 13 October 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "500 Miglia di Monza Heat 2". ChampCarStats.com. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "500 Miglia di Monza Heat 3". ChampCarStats.com. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "1958 500 Miglia di Monza Heat 2". ChampCarStats.com. 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "A history of the Italian Grand Prix". Formula1.com. Formula One Administration Ltd. 8 September 2004. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "The hidden history of the Monza banking". Formula1.com. Formula One Administration Ltd. 30 August 2005. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Monza year Book 1965

- "1972–1978: Chicane and variants to reduce the high speed". Autodromo Nazionale Monza. MonzaNet.it. 2007. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "1979–1988: New works to update the circuit". Autodromo Nazionale Monza. MonzaNet.it. 2007. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "1989–1997: New pit complex and the interventions for the security". Autodromo Nazionale Monza. MonzaNet.it. 2007. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "New Monza over a second faster for F1 – and Parabolica gravel will return". F1 Fanatic. 1 June 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "McLaren Formula 1 - 2015 Italian Grand Prix Preview". McLaren. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- "Bigger kerbs installed for Monza chicanes". formula 1.com. 8 September 2009. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- "Formula 1 Gran Premio Heineken d'Italia 2020 – Race Maximum Speeds" (PDF). Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 6 September 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- Golson, Jordan. "The Ultra-Fast F1 Track Where the Biggest Problem Is Slowing Down". Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- "Formula 1 Gran Premio Heineken d'Italia 2020 – Qualifying Session Final Classification" (PDF). Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 5 September 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- "Statistics Drivers - Misc - Fastests qualifications • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com.

- "Grand Prix death casts doubt over Monza circuit". CNN. 11 September 2000. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Autodromo Nazionale Monza. |