2002 Australian Grand Prix

The 2002 Australian Grand Prix (formally the LXVII Foster's Australian Grand Prix) was a Formula One motor race held on 3 March at the Melbourne Grand Prix Circuit. With 127,000 people in attendance, the race was the first of the 2002 Formula One World Championship and the 18th edition of the race in Formula One. Ferrari driver Michael Schumacher won the 58-lap race from starting in second position. Juan Pablo Montoya of Williams finished second and Kimi Räikkönen took third for the McLaren team.

| 2002 Australian Grand Prix | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Race 1 of 17 in the 2002 Formula One World Championship

| |||||

| |||||

| Race details[1][2] | |||||

| Date | 3 March 2002 | ||||

| Official name | LXVII Foster's Australian Grand Prix | ||||

| Location | Melbourne Grand Prix Circuit, Albert Park, Melbourne, Australia | ||||

| Course | Temporary street circuit | ||||

| Course length | 5.303 km (3.295 mi) | ||||

| Distance | 58 laps, 307.574 km (191.118 mi) | ||||

| Weather | Cloudy at start, clearing to sunny skies. | ||||

| Attendance | 127,000 | ||||

| Pole position | |||||

| Driver | Ferrari | ||||

| Time | 1:25.843 | ||||

| Fastest lap | |||||

| Driver |

| McLaren-Mercedes | |||

| Time | 1:28.541 on lap 37 | ||||

| Podium | |||||

| First | Ferrari | ||||

| Second | Williams-BMW | ||||

| Third | McLaren-Mercedes | ||||

|

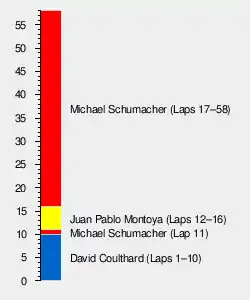

Lap leaders

| |||||

Ferrari's Rubens Barrichello qualified on pole position by recording the fastest lap in qualifying. He retired at the start of the race, when he braked early for the first corner, catching out Williams driver Ralf Schumacher, who hit the rear of Barrichello's car. Six drivers were involved in a separate incident. The safety car was deployed for four laps to clear the track. McLaren's David Coulthard led the first ten laps until an error on lap eleven allowed Michael Schumacher to pass him. Montoya then passed Schumacher for first place at the beginning of lap twelve. He kept the lead until he ran wide and Michael Schumacher overtook him to reclaim it. He led the rest of the race to take his third win in Australia and the 54th of his career.

Following this, the first round of the season, Michael Schumacher left Australia leading the World Drivers' Championship with ten points. Montoya was four points behind in second with Räikkönen third. In the Constructors' Championship, Ferrari led with ten points followed by Williams and McLaren with sixteen races left in the season.

Background

.jpg.webp)

Preparations for the event began in January 2002. At the time, it was only on the provisional calendar of the 2002 Formula One World Championship due to the death of marshal Graham Beveridge in an accident in the 2001 race.[3] Formula One's governing body, the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA), later confirmed it would proceed as scheduled following the publication of a coroner's report ruling Beveridge's death "avoidable".[4] It was the first of 17 races of 2002 and the 18th Formula One World Championship Australian race. It occurred at the 5.303 km (3.295 mi) Melbourne Grand Prix Circuit in the Melbourne suburb of Albert Park on 3 March.[1] To improve safety, the height of the safety fences was raised to 3.8 m (12 ft), cages to safeguard race officials were installed and the size of access openings reduced.[5]

Heading into the new season, several teams retained the same line-up as they had in 2001, however some teams changed drivers for 2002. The Benetton team was renamed Renault, ending its 16 year involvement in Formula One,[6] and the Japanese car maker Toyota debuted with drivers Allan McNish and Mika Salo after it spent 2001 developing the TF102.[7] The Prost team was liquidated in January 2002 after it was unable to locate money from sponsors or a buyer to remain solvent.[8] The two-time world champion Mika Häkkinen took a sabbatical and fellow Finn Kimi Räikkönen replaced him at McLaren,[9] whose Sauber car was driven by Felipe Massa, the 2001 Euro Formula 3000 champion.[10] At the Jordan team, the 2001 British Formula Three champion Takuma Sato paired with Giancarlo Fisichella,[11] whom Jarno Trulli replaced at Renault.[12] Former Prost driver Heinz-Harald Frentzen drove Jos Verstappen's Arrows car,[13] and Fernando Alonso left Minardi to become Renault's test driver; he was replaced by International Formula 3000 competitor Mark Webber.[14]

At the front of the field, the press and bookmakers considered Ferrari's Michael Schumacher the favourite to take his fifth World Drivers' Championship, with the Williams driver Juan Pablo Montoya predicted to be his main challenger.[15][16][17] Schumacher said his objective for the season was to win the championship and equal Juan Manuel Fangio's all-time record of five titles, "Our motivation is still unchanged, our target and goals are still the same. We want to once again win both world championships and there is nothing nicer than winning with Ferrari."[18] Montoya declared that he was more relaxed than he was in 2001 because he knew his team better, "I think I showed everyone out there that I am competitive and that's the important thing. It was a lot harder to win in Formula One than in CART because it took longer to understand the car, but now that's done I'm looking to do better in 2002."[19] Former driver Derek Warwick believed Michael Schumacher was the best driver in the sport and suspected Montoya was not emotionally mature.[20]

Ferrari brought the F2001 in lieu of the F2002 to Australia due to performance and reliability issues. According to the Ferrari team principal Jean Todt, the F2002 was fast in pre-season testing but the team had not the time available to be certain that it would be reliable in Australia, "We think it will be able to bring home valuable points for the championship. Next week, we will continue our on-track development of the F2002, as well as fine-tuning the F2001 for the first race."[21] During the first two practice sessions, the F2001 was fitted with a rear wing used on the F2002 in testing; both Michael Schumacher and his teammate Rubens Barrichello opted for one seen at the 2001 Japanese Grand Prix. The McLaren MP4-17 car featured an attachment to its lower front suspension frame split to promote airflow under the front wing, and revised ailerons were equipped to the front and rear of the car. The Jordan, Arrows and Sauber teams copied the design.[22]

Practice

Four practice sessions were held before the Sunday race, two each on Friday and Saturday. The Friday morning and afternoon sessions each lasted an hour; the third and fourth sessions, on Saturday morning, lasted 45 minutes each.[23] In the first session, which was held in variable weather leading to the fastest times late on,[24] Michael Schumacher lapped fastest with a time of 1 minute, 28.804 seconds, 0.363 seconds faster than his teammate Barrichello in second. Fisichella, Ralf Schumacher, Massa, the Jaguar duo of Pedro de la Rosa and Eddie Irvine, Frentzen, Salo and Renault's Jenson Button rounded out the session's top ten drivers.[25]

Michael Schumacher set the day's fastest lap, a 1 minute, 27.276 seconds, in the second session. His teammate Barrichello was 0.523 seconds slower in second place. The two Williams cars of Ralf Schumacher and Montoya, Nick Heidfeld of the Sauber team, Salo, Räikkönen, Massa, Fisichella and Trulli were in positions three to ten.[26] During the session, Enrique Bernoldi stopped his Arrows A23 car with a broken gearbox.[27] Barrichello spun through 360 degrees across the grass and reemerged onto the circuit soon after.[28] Montoya braked too late and returned to the track via an escape road and a gravel trap. A short light rain shower made the circuit slippery and caught out Alex Yoong; he beached his Minardi car in the turn one gravel trap. An engine failure ended Fisichella's session early and his teammate Sato ran across a gravel trap.[28]

The weather for the third session was cool, damp and overcast.[29][30] Ferrari continued to be fastest with a revised unofficial lap record of 1 minute, 26.177 seconds from Michael Schumacher. Barrichello was 0.321 seconds slower in second.[29] McLaren's Coulthard and Räikkönen, Williams' Ralf Schumacher and Montoya, British American Racing (BAR) driver Olivier Panis, Sauber teammates Heidfeld and Massa along with Trulli followed in the top ten.[30] With 13 minutes and 34 seconds to go, Sato lost control of the rear of his Jordan EJ12 car on the entry to Stewart turn and crashed into the left-hand side tyre barrier at 160 km/h (99 mph).[31][32] Sato was unhurt;[30] practice was stopped for nine minutes to allow marshals to clean the track.[31] Since spare cars could not be used in free practice, Sato missed the fourth session since his car required repairs.[32]

In the fourth session, a brief rain shower dampened the circuit, which prevented an improvement in lap times as some drivers went off the track. Hence, no driver bettered Michael Schumacher's fastest time, as Barrichello in second halved the gap to his teammate. The Williams duo of Montoya and Ralf Schumacher improved to third and fourth and the McLaren pair of Coulthard and Räikkönen fell to fifth and sixth. Heidfeld, the BAR duo of Jacques Villeneuve and Panis and Fisichella were seventh to tenth.[33]

Qualifying

Saturday's afternoon one-hour qualifying session saw each competitor limited to twelve laps, with the starting order decided by their fastest laps. During this session, the 107% rule was in effect, which necessitated each driver set a time within 107 per cent of the quickest lap to qualify for the race.[23] The session began on a dry track until a heavy rainstorm fell halfway through, making the circuit slippery and prevented any improvement in lap time.[34][35] Barrichello completed two laps before it rained (the first was compromised by slower traffic);[36] he took the fourth pole position of his career and his first since the 2000 British Grand Prix with a time of 1 minute, 25.843 seconds.[34] He was joined on the grid's front row by Michael Schumacher, who made an error on a kerb in the first third of a lap.[35][37] Ralf Schumacher, third, remained in the garage for the first three minutes to avoid slower traffic.[36] Fourth-placed Coulthard attempted to pass an unsighted Villeneuve on the outside at the final turn and they made contact. Coulthard hit the wall with his right-rear wheel and spun onto a run-off area.[35] A error put his teammate Räikkönen fifth.[37] Montoya in sixth lost six-tenths of a second after Fisichella slowed his first timed lap. Trulli in seventh was slowed by a Jaguar car on his first lap. Fisichella in eighth expressed satisfaction with the balance and performance of his car.[36] Massa was the highest-placed rookie in ninth after two errors. His teammate Heidfeld qualified tenth.[35][36]

Button was the fastest driver not to qualify in the top ten after he was fourth early on. Panis completed one timed lap as he could not extract more performance from his BAR 004 and took 12th.[36] Excess oversteer slowed his teammate Villeneuve in 13th.[37] Salo, 14th, drove cautiously on his first timed lap. A minor fuel pressure fault limited Frentzen in 15th to one untroubled lap.[36] McNish, 16th, had one set of tyres deducted from his qualifying allocation because Toyota mistakenly used one set assigned for the Friday practice sessions on Saturday. A stoppage caught out Bernoldi at the start of his first timed lap and he qualified 17th. Webber took 18th and used wet-weather tyres.[37] The two Jaguar R3 cars had a major aerodynamic deficiency and were 19th and 20th:[38] A rear brake balance slowed Irvine and a handling deficiency saw de la Rosa drive the spare Jaguar.[36] Yoong completed one timed lap for 21st.[37] Five minutes in Sato's spare Jordan EJ12 car stopped before Stewart turn with a hydraulic clutch problem that automatically selected third gear. The session was stopped for eight minutes to allow marshals to move his car. Sato returned to his garage and drove Fisichella's race car but the rain made him more than 107 per cent slower than Barrichello.[39]

Post-qualifying

After qualifying, the Jordan team principal and owner Eddie Jordan appealed to the stewards to allow Sato to participate in the race because he was under the 107 per cent limit during free practice. They permitted him to start under "exceptional circumstances" as in the case of previous cases affected by changeable weather.[39][40]

Qualifying classification

- Notes

- ^1 – Takuma Sato set a time 107% slower than the fastest qualifying lap. He was granted permission from the stewards to start the race due to "exceptional circumstances".[40]

Warm-up

A half-hour warm-up session was held on Sunday morning in variable weather as heavy rain fell before it commenced.[23][43] Teams used rain tyres and set-up their cars against the weather of the time.[44] With a lap of 1 minute and 41.509 seconds, Michael Schumacher was fastest with teammate Barrichello 1.382 seconds slower in second position. Coulthard, Ralf Schumacher, Montoya, Massa, Heidfeld, Fisichella, Trulli and Irvine made up positions three to ten.[45] With 40 seconds to go,[46] Salo drove off the racing line to allow Barrichello past into Ascari corner. He drove onto a white painted line, lost control of his Toyota and crashed into the barrier; Salo's front wing detached heading towards an escape road.[43][44][46]

Race

The weather at the start was dry and overcast with the air temperature between 15 to 18 °C (59 to 64 °F) and the track temperature from 20 to 23 °C (68 to 73 °F).[47][48][49] A total of 127,000 people attended the event.[50] Sato drove the spare Jordan EJ12 car set up for his teammate Fisichella; after warm-up the Jordan team rectified an electrical problem that rendered its clutch inoperable.[51] Before the race commenced at 14:00 local time,[23] Frentzen and Bernoldi stalled their stationary cars; marshals and mechanics extricated them to the pit lane.[52][53]

Ralf Schumacher used the grip on the outside to pass Michael Schumacher for second position and challenged the heavily fuelled Ferrari of Barrichello for the lead.[54][55] As Michael Schumacher turned left to provide himself with the best possible entry for Brabham corner, his teammate Barrichello switched lanes twice to try and block Ralf Schumacher, who responded by turning to the centre in anticipation that momentum would move him into the lead.[56] Barrichello braked early for Brabham turn and caught out Ralf Schumacher,[55] who struck the rear of Barrichello's car at about 240 km/h (150 mph).[48] He launched over the Ferrari,[53] grazed Barrichello's helmet,[50] careened 100 m (330 ft) and rested against the tyre wall.[2][57] Barrichello's rear wing was removed from his car, spinning broadside to a stop and caused an eight-car accident.[55] His teammate Michael Schumacher and Räikkönen drove onto the grass to avoid a collision,[2][53] as Fisichella hit the Sauber cars of Heidfeld and Massa, causing Button, Panis and McNish to get caught up in the incident. Villeneuve, Salo, Webber, Irvine, de la Rosa, Yoong and Sato negotiated their way through the crash scene.[2]

The drivers involved in the crash returned to the pit lane in anticipation that the race would be stopped and could drive their spare cars for a restart. However, the FIA race director Charlie Whiting did not stop the race and order a restart since no driver was injured. He deployed the safety car with the damaged cars moved and debris cleared.[54][58] This left Coulthard in the lead, followed by Trulli, Montoya, Michael Schumacher, Irvine and de la Rosa.[47] At the conclusion of lap two, Räikkönen entered the pit lane for a 48-second pit stop for a new front wing and to remove debris lodged behind his back.[2][53][55] Webber's differential and traction control began to malfunction on lap three.[59] On the same lap, Frentzen ignored a red light instructing drivers to remain in the pit lane until further notice and ventured onto the circuit.[49][52] The safety car was withdrawn at the conclusion of the fifth lap and Coulthard led Trulli and Montoya.[47] Going into Whiteford turn,[48] Montoya drew close to Trulli and slid wide on oil laid on the circuit.[54][58] Michael Schumacher used Montoya's error to overtake him for third place.[60] Further down the field, Räikkönen moved from eleventh to ninth position.[53]

Coulthard began to pull away from the rest of the field, increasing his lead to four-and-a-half seconds by lap seven.[47] That same lap, Sato overtook de la Rosa for sixth place, as Webber lost seventh position to Räikkönen.[53] At the back, Bernoldi rejoined the race after switching from his race car to the spare Arrows vehicle.[2] Trulli blocked Michael Schumacher from passing him for second into Brabham corner on the eighth lap, allowing Montoya to gain on Schumacher; he was not close enough to affect a pass.[48] There were overtakes further down the field: Räikkönen passed de la Rosa and Sato as Villeneuve overtook Webber for ninth.[53] During lap nine, Trulli lost control of the rear of his Renault on oil at the exit to Jones turn, and broke his suspension in a collision with the inside barrier.[48][55] Because Trulli was stopped on the centre of the track,[49][61] the safety car was deployed for the second time to allow marshals to move his car.[47] When the safety car was withdrawn at the end of the 11th lap, an electrical fault distracted Coulthard, causing him to miss a gear change,[55][56] lock his brakes,[49] and understeer wide onto the grass entering Prost turn.[48] He fell to fifth.[49]

Michael Schumacher moved into the lead with Montoya second and Irvine third.[61] On the approach to Brabham corner Montoya's higher straightline speed allowed him to overtake Michael Schumacher on the outside at the end of the main straight for the lead.[2] Montoya then steered onto the inside to maintain the lead from Schumacher at Jones corner.[55] By the 13th lap, Michael Schumacher had close to within eight-tenths of a second to affect a pass on Montoya,[49] which he was unable to do because of slower traffic.[48] On lap 14,[53] Sato retired in the pit lane with an unrectifiable electronics issue that limited his gear selection.[62] Michael Schumacher continued to pressure Montoya into an error,[55] and caused the latter to drive onto oil at Brabham corner.[2] He overtook Montoya on the inside at the exit of Jones turn to take the lead at the start of lap 17.[48][56] Michael Schumacher began to pull away from the rest of the field as Montoya struggled to generate heat in his tyres. On lap 18, de la Rosa fell to eighth after Yoong, Webber and Villeneuve overtook him. On the following lap Frentzen was disqualified for his earlier transgression of ignoring the red light at the exit of the pit lane.[53]

By the 22nd lap Michael Schumacher increased his lead over Montoya to 11.3 seconds with consecutive lap times in the 1 minute and 29 seconds range.[2][60] Räikkönen was eight-tenths of a second behind Montoya.[49] On the same lap, Coulthard went off the track at Prost corner. His reduced speed meant Irvine passed him for fourth soon after.[48] On lap 23 Bernoldi was disqualified from the race because the stewards deemed him to have switched to the spare car after the race began.[55] Webber and Villeneuve passed Coulthard for fifth and sixth on laps 25 and 26.[48][53] Villeneuve in sixth had a rear wing failure that sent him into the tyre wall at high speed on the entry to Waite corner and retirement from his 100th race entry on lap 28.[49][53][57] He was unhurt. On lap 29, Yoong overtook Coulthard for sixth position.[53] Seven laps later, Coulthard became the race's final retirement when he pulled off to the side of track at Whiteford corner because his McLaren was stuck in sixth gear.[2][49]

.jpg.webp)

Webber was the first of the top six drivers to make a pit stop on lap 37.[48] He had a problematic 34.9 second pit stop; the Minardi's fuel cover did not open automatically and a mechanic used a screwdriver to unsecure it. Webber rejoined the track in sixth position.[63] Montoya and Michael Schumacher made their pit stops on laps 37 and 38.[61] In the meantime, Räikkönen recorded the race's fastest lap of 1 minute, 25.841 seconds on lap 37,[2] as he sought to pass Montoya for second position after his pit stop.[55] He made his stop on lap 38.[53] As Räikkönen drove onto the track, he drew alongside Montoya and carried excess speed into Brabham corner.[55] He understeered wide onto the grass as he regained control of the rear of his car and fell to third, behind Montoya.[47][48]

With the first four positions settled, attention switched to the battle for fifth between Webber and Salo.[53] Webber short shifted to prevent unneeded car component stress and noticed Salo closing up. He went faster and the Minardi team owner Paul Stoddart radioed that he had to defend fifth from Salo. Webber was aware of a potential revenue bonus of $25 million for Minardi if they finished ahead of Toyota in the World Constructors' Championship.[59] Salo had been aware of the distance between himself and Webber and closed up to the latter by the 57th lap.[55] He attempted to pass Webber; the aerodynamic turbulence created of airflow over Webber's car and the latter's block caused Salo to spin through 180 degrees on radiator coolant from Button's car at Whiteford turn. Salo was able to restart his car and continue in sixth.[47][48][64]

Michael Schumacher led the final 39 laps to take his third successive Australian Grand Prix victory and the 54th of his career.[58] Montoya was 18.628 seconds behind in second position. He was a further 6.4 seconds ahead of Räikkönen,[2] who took the first podium finish of his career in third.[58] Irvine and Webber finished fourth and fifth after starting from 19th and 18th respectively.[48][58] Salo took the final point in sixth place, the first time a team scored points in its debut race since JJ Lehto finished fifth for Sauber at the 1993 South African Grand Prix.[65] Yoong came seventh with a "long" brake pedal and a car optimised for wet-weather;[62] marshals mistakenly waved blue flags at Yoong because they did not know which lap he was on.[64] De la Rosa was the final classified finisher after a misfiring engine required him to undergo a lengthy pit stop. The attrition rate was high, with eight of the twenty-two starters finishing the race.[2][57]

Post-race

The top three drivers appeared on the podium to collect their trophies and spoke to the media in a later press conference.[23] Michael Schumacher called his battle with Montoya "an interesting one" and "a bit back and forward", adding "I think as well that the tyres played a little bit of a role in that; initially I struggled to get the temperature in where these guys seemed to get faster on top of temperatures but then it went the other way around, their tyres went off and my one came in so I had a nice chance to battle a little bit and finally got first position for us, which was ideal."[66] Montoya said he enjoyed the battle and stated Ferrari had the fastest car, "I think the conditions were not the best for the tyres. Hopefully in Malaysia it is going to be hotter, it could play into our hands a little bit."[66] Räikkönen said he was surprised to finish third and talked about the ease of overtaking other cars, "Some cars was more difficult and then it was helping me a lot big time because the safety car came out second time and I got behind the leaders and that was the main reason that I catch them, but it was quite a difficult and interesting race."[66]

Ron Walker, the chairman of the Australian Grand Prix Corporation, persuaded Webber and Stoddart to celebrate their fifth-place result with an impromptu ceremony on the podium, which led to a fine of £50,000 from the FIA president Max Mosley.[67] In a retrospective interview for The Weekend Australian in 2012, Stoddart called Webber's fifth-place finish "the most exciting two points in the history of Formula One".[67] Webber commented on the result, "Finishing the race fifth was unbelievable. We had people scaling catch fencing. Occupational health and safety would have gone ballistic these days. It was a unique day."[67] The result saw Webber's three-race contract with Minardi extended to the end of the season.[67] The media compared Webber's achievement to the ice skater Steven Bradbury winning a gold medal in the men's 1000 metres short track speed skating at the 2002 Winter Olympics; both men were successful after several participants crashed in their respective events.[63][68]

Following their collision, their third in the past two seasons, Barrichello and Ralf Schumacher were summoned to meet the stewards, who reviewed television footage post-race. Neither driver received a penalty and were given a warning.[69] The stewards classed the crash as "a racing incident", with neither competitor to blame.[50] Ralf Schumacher argued Barrichello braked earlier than normal, saying "I was afraid to turn into the first corner because I suddenly saw cars flying next to me. I decided to go straight on and have a nice ride through the grass, which was a good decision, otherwise I guess I would have been hit."[50] Barrichello said he was not to blame for the accident, "If he wanted to overtake on the outside, he should have moved a lot further. I didn't get in his way."[50] Jackie Stewart, the three-time world champion, argued Ralf Schumacher had misjudged the braking distance for turn one,[70] while Coulthard stated his belief Barrichello caused the accident by braking earlier than usual.[71]

Whiting's decision not to stop the race after the eight-car crash was criticised. The technical director of the Jordan team Gary Anderson called it "the most absurd thing I've seen in my life".[54] Fisichella believing not stopping the race was "ridiculous",[62] and Michael Schumacher agreed it should have been stopped.[66] Coulthard defended the decision, saying "I've always felt that to deprive the spectators of a number of cars as a result of an incident at the first corner isn't really good for the business. But this isn't Hollywood. You don't cut out the bits you don't like. This is real. This is racing."[56] Ralf Schumacher also backed Whiting's ruling, noting "Charlie Whiting took the right decision by not stopping the race. He had made it quite clear to us that he would not stop a race unless it was for safety reasons and that wasn't the case."[72]

Because this was the first race of the season, Michael Schumacher led the World Drivers' Championship with ten points. Montoya was second with six points and Räikkönen was third with four. Irvine was fourth with three points and Webber was fifth with two points.[2] Ferrari took the lead of the World Constructors' Championship with ten points. Williams were second with six points and McLaren followed in third with four points. With three points, Jaguar were fourth and Minardi fifth with two points with sixteen races left in the season.[2]

Race classification

Drivers who finished in the top six points-scoring positions are denoted in bold.

| Pos | No. | Driver | Constructor | Laps | Time/Retired | Grid | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Ferrari | 58 | 1:35:36.792 | 2 | 10 | |

| 2 | 6 | Williams-BMW | 58 | +18.628 | 6 | 6 | |

| 3 | 4 | McLaren-Mercedes | 58 | +25.067 | 5 | 4 | |

| 4 | 16 | Jaguar-Cosworth | 57 | +1 Lap | 19 | 3 | |

| 5 | 23 | Minardi-Asiatech | 56 | +2 Laps | 18 | 2 | |

| 6 | 24 | Toyota | 56 | +2 Laps | 14 | 1 | |

| 7 | 22 | Minardi-Asiatech | 55 | +3 Laps | 21 | ||

| 8 | 17 | Jaguar-Cosworth | 53 | +5 Laps | 20 | ||

| Ret | 3 | McLaren-Mercedes | 33 | Gearbox | 4 | ||

| Ret | 11 | BAR-Honda | 27 | Broken wing | 13 | ||

| Ret | 10 | Jordan-Honda | 12 | Electrical | 22 | ||

| Ret | 14 | Renault | 8 | Spun off | 7 | ||

| Ret | 2 | Ferrari | 0 | Collision | 1 | ||

| Ret | 5 | Williams-BMW | 0 | Collision | 3 | ||

| Ret | 9 | Jordan-Honda | 0 | Collision | 8 | ||

| Ret | 8 | Sauber-Petronas | 0 | Collision | 9 | ||

| Ret | 7 | Sauber-Petronas | 0 | Collision | 10 | ||

| Ret | 15 | Renault | 0 | Collision | 11 | ||

| Ret | 12 | BAR-Honda | 0 | Collision | 12 | ||

| Ret | 25 | Toyota | 0 | Collision | 16 | ||

| DSQ | 20 | Arrows-Cosworth | 16 | Disqualified2 | 15 | ||

| DSQ | 21 | Arrows-Cosworth | 15 | Disqualified2 | 17 | ||

| Sources:[42] | |||||||

- Notes

- ^2 – Heinz-Harald Frentzen and Enrique Bernoldi were disqualified for passing the red light at the exit of the pit lane and changing to the team's spare car after the commencement of the race, respectively.[55]

Championship standings after the race

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Note: Only the top five positions are included for both sets of standings.

References

- "2002 Australian GP: LXVII Foster's Australian Grand Prix". Chicane F1. Archived from the original on 17 July 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Grand Prix Results: Australian GP, 2002". GrandPrix.com. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 16 June 2002. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Australian Grand Prix awaits FIA approval". SportBusiness. 14 January 2002. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Formula 1: Green light for Australian Grand Prix". Irish Examiner. 8 February 2002. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Phillips, Shaun (1 March 2002). "Champ's green light for safety measures". Herald Sun. p. 007. Retrieved 7 September 2019 – via Gale OneFile: News.

- Allsop, Derick (17 March 2000). "Renault return to F1 with Benetton buy-out". The Independent. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Toyota will surprise – Haug". Sportal. 13 December 2001. Archived from the original on 7 May 2002. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Petrequin, Samuel (28 January 2002). "Prost's F1 Team Shut Down". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Henry, Alan (1 March 2002). "Coulthard ready to wear the trousers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 June 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Sauber aim to consolidate". BBC Sport. 25 January 2002. Archived from the original on 25 February 2003. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Himmer, Alastair (10 October 2001). "Jordan Announce Sato Deal". Atlas F1. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Hynes, Justin (23 August 2001). "Fisichella back at Jordan". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Verstappen not happy with Arrows". motorsport.com. 14 February 2002. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Minardi · KL Minardi Asiatech". The Age. 27 February 2002. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Mossop, James (23 February 2002). "Schumacher sets the standard". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 February 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Schumacher Odds-On Favourite for 2002 Title". Atlas F1. 11 February 2002. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "2002 Preview: Montoya shapes up to take Schumacher's crown". F1Racing.net. 26 February 2002. Archived from the original on 30 September 2004. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Schumacher eyes fifth crown". BBC Sport. 6 February 2002. Archived from the original on 13 February 2002. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Ristic, Ivan (25 January 2002). "Montoya – more relaxed and ready to fight". F1Racing.net. Archived from the original on 28 August 2004. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Warwick Downplays Montoya's Challenge". Atlas F1. 15 February 2002. Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Champions to start year in '01 model". ESPN. Reuters. 19 February 2002. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Piola, Giorgio (5–11 March 2002). "McLaren ad alto potenziale". Autosprint (in Italian) (10): 26–29.

- "2002 Formula One Sporting Regulations" (PDF). Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 31 October 2001. pp. 12–14, 19 & 25–26. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- "Practice 1: Schuey fastest shock". Autosport. 1 March 2002. Archived from the original on 8 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Friday First Free Practice – Australian GP". Atlas F1. 1 March 2002. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Friday Second Free Practice – Australian GP". Atlas F1. 1 March 2002. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Bulletin N°1 – Free Practice". Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. Archived from the original on 16 June 2002. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Old Ferrari still class of the field". F1Racing.net. 1 March 2002. Archived from the original on 30 September 2004. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Schumi smashes track record". BBC Sport. 2 March 2002. Archived from the original on 4 April 2002. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Saturday First Free Practice – Australian GP". Atlas F1. 1 March 2002. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Ferrari continue masterclass". F1Racing.net. 2 March 2002. Archived from the original on 29 September 2004. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Sato shunt halts first practice". Autosport. 1 March 2002. Archived from the original on 8 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Free practice 4: Schuey still on top". Autosport. 1 March 2002. Archived from the original on 8 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Ferrari's Barrichello takes Melbourne pole". Rediff.com. Reuters. 2 March 2002. Archived from the original on 9 November 2005. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Qualifying: Rain gives Rubens pole". Autosport. 2 March 2002. Archived from the original on 8 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Saturday's Selected Quotes – Australian GP". Atlas F1. 2 March 2002. Archived from the original on 24 December 2004. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Bulletin N°2 – Free Practice and Qualifying". Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 2 March 2002. Archived from the original on 20 April 2002. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Rae, Richard (3 March 2002). "Smiles better; Motor racing". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 8 September 2019 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- Henry, Alan, ed. (2002). Autocourse 2002–2003. Hazleton Publishing Ltd. p. 91. ISBN 1-903135-10-9.

- Lynch, Michael (3 March 2002). "Sato gets start, but only just". The Sunday Age. p. 13. Retrieved 9 September 2019 – via Gale OneFile: News.

- "Australian GP Saturday qualifying". motorsport.com. 2 March 2002. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- "2002 Australian Grand Prix results". ESPN. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Ferrari makes clean sweep in Melbourne so far". Formula One. 2 March 2002. Archived from the original on 4 April 2002. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Bulletin N°3 – Warm-up". Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 28 June 2002. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Collings, Timothy (2 March 2002). "Sunday Warm Up – Australian GP". Atlas F1. Archived from the original on 24 December 2004. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Warm-up: Schumacher out front". Autosport. 2 March 2002. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Schumi wins thrilling season opener". F1Racing.net. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 30 September 2004. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Lap-by-lap from Melbourne". ITV-F1. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 6 March 2002. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "2002 – Round 1 – Australia: Melbourne". Formula One. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 5 October 2002. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Gordon, Ian (4 March 2002). "Formula One: Schumacher exhibits luck of champion". Press Association.

- "More drama for Jordan as Sato starts in spare". GPUpdate. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 30 September 2004. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Schumacher claims attrition-filled Australian GP". motorsport.com. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Bulletin N°4 – Race Facts and Incidents". Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 16 June 2002. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Tremayne, David (4 March 2002). "Motor racing: Schumacher dodges melee to seal win; Australian Grand Prix Almost half the field eliminated in dramatic crash at start of race as world champion romps to commanding victory". The Independent. p. 1. Retrieved 9 September 2019 – via Gale General OneFile.

- "Australian GP 2002 – Schu escapes to victory". Crash. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Williams, Richard (4 March 2002). "Motor Racing: Pile-up leaves the way clear for Ferrari: Schumacher in command after eight-car shunt in Melbourne". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 September 2019 – via Gale General OneFile.

- Eason, Kevin (4 March 2002). "Schumacher slips past wreckage to stake early claim; Motor racing". The Times. p. 31. Retrieved 11 September 2019 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- Spurgeon, Brad (4 March 2002). "Formula One: Schumacher stays clear of trouble". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Webber, Mark (2015). [ittps://archive.org/details/aussiegritmyform0000webb Aussie Grit: My Formula One Journey]. Sydney, Australia: Pan Macmillan Australia. pp. 322–335. ISBN 978-1-5098-1353-7.

- Mauk, Eric (3 March 2002). "Michael Schumacher Starts Title Defense in Style". Speed. Archived from the original on 14 June 2002. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Australian GP clockwatch". BBC Sport. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 6 March 2002. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Sunday's Selected Quotes – Australian GP". Atlas F1. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 24 December 2004. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Henry, Alan (5 March 2002). "Webber rides his beginners' luck to lift Minardi". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 June 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Vigar, Simon (2008). Forza Minardi!: The Inside Story of the Little Team Which Took on the Giants of F1. Poundbury, England: Veloce Publishing. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-1-84584-160-7.

- "Historic Day for New Boys Toyota". Atlas F1. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 24 December 2004. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "Post-Race Press Conference – Australian GP". Atlas F1. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 24 December 2004. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Le Grand, Chip (16 March 2012). "The day Webber drove his clunker into nation's hearts". The Weekend Australian. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Over-the-top style clears way for Webber to do a Bradbury". The Sydney Morning Herald. 4 March 2002. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Rubens, Ralf get off with a warning". motorsport.com. 7 March 2002. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Drivers spared thanks to safety standards, says Stewart". The Herald. 4 March 2002. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Gover, Paul (4 March 2002). "Reminder of past tragedy". Herald Sun. p. 004. Retrieved 11 September 2019 – via Gale OneFile: News.

- "Ralf Supports Stewards Decision". Atlas F1. 3 March 2002. Archived from the original on 24 December 2004. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

| Previous race: 2001 Japanese Grand Prix |

FIA Formula One World Championship 2002 season |

Next race: 2002 Malaysian Grand Prix |

| Previous race: 2001 Australian Grand Prix |

Australian Grand Prix | Next race: 2003 Australian Grand Prix |