56th (West Essex) Regiment of Foot

The 56th (West Essex) Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment in the British Army, active from 1755 to 1881. It was originally raised in Northumbria as the 58th Regiment, and renumbered the 56th the following year when two senior regiments were disbanded. It saw service in Cuba at the capture of Havana in the Seven Years' War, and was later part of the garrison during the Great Siege of Gibraltar in the American Revolutionary War. During the French Revolutionary Wars it fought in the Caribbean and then in Holland. On the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars the 56th raised a second battalion in 1804 as part of the anti-invasion preparations; both saw service in India and in the Indian Ocean, with the first capturing Réunion and Mauritius. A third battalion was formed in the later years of the war, but was disbanded after a brief period of service in the Netherlands.

| 56th (West Essex) Regiment of Foot | |

|---|---|

Cap badge of the 56th (West Essex) Regiment of Foot | |

| Active | 1755–1881 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Line Infantry |

| Size | One battalion (two battalions 1804–1817) |

| Garrison/HQ | Warley Barracks, Brentwood |

| Nickname(s) | The Pompadours |

| Motto(s) | Montis insignia Calpe (Badge of the Rock of Gibraltar) |

| Colors | Purple facings to uniform |

| March | Rule, Britannia! |

| Engagements | Seven Years' War American Revolutionary War French Revolutionary Wars Napoleonic Wars Crimean War |

| Battle honours | Havannah;[1] Moro; Gibraltar; Sevastopol |

The regiment spent much of the following period on foreign garrison duties, and saw service in the later stages of the Crimean War, at the Siege of Sevastopol. It was despatched to India during the Indian Mutiny, but did not see active service. The regiment was amalgamated with the 44th (East Essex) Regiment of Foot to form the 2nd Battalion of the Essex Regiment in 1881, as part of the Childers Reforms; the Essex Regiment's lineage is currently maintained by the 1st Battalion, Royal Anglian Regiment, a mechanised infantry unit.

History

Formation and early service

Following the rise of tensions in North America in 1755, the British government decided to raise ten regiments of infantry in preparation for an expected war with France. Orders for the raising of the 52nd to 61st Regiments of Foot were issued in December of that year.[2]

One of these regiments, the 58th Regiment of Foot, was raised at Newcastle and Gateshead on 28 December 1755, under the colonelcy of Lord Charles Manners, whose commission was dated 26 December. Throughout 1756 it recruited heavily to come to its authorised establishment of ten companies, each of 78 men. On 25 December 1756, the 50th and 51st Regiments were disbanded, and all higher-numbered units redesignated, with the 58th becoming the 56th Regiment of Foot.[3]

In April 1757 it moved to Berwick, and thence into Scotland, where it would take up garrison duties; it occupied quarters at Aberdeen in 1758 and Edinburgh in 1759. In July 1760 it returned to England, sailing from Leith to Portsmouth, and was stationed at Hilsea through 1761. On 17 December of that year, Lord Charles Manners was succeeded in the colonelcy by Colonel William Keppel.[4]

West Indies campaign

On 4 January 1762, Britain declared war on Spain in the Seven Years' War, and began preparing for an expedition against Spanish possessions in the Caribbean. The 56th was assigned as part of the expeditionary force, and sailed from Portsmouth on 5 March, arriving off Havana on 6 June and landing the following day. The regiment numbered a total of 933 officers and men, and was brigaded with four companies of the 1st Foot and a battalion of the 60th Foot.[5]

The main object of the force was to besiege Morro Castle, which guarded the harbour. After a long reduction, a storming party was organised and attacked on 30 July, and took the fort after a brief but violent action, in which 150 of the garrison were killed and 400 taken prisoner, with the remaining 200 dying in an attempt to escape in small boats.[6] The regiment was granted the battle honour "The Moro" for this action.[7]

The city surrendered on 13 August.[8] The regiment suffered twelve deaths, with one officer and 23 men wounded, during the campaign. The 56th remained as part of the Havana garrison for the following year, until Cuba was returned to Spain by the Treaty of Paris, when it was transported to Ireland, arriving in Limerick in October 1763. The regiment moved to Dublin in May 1765, and in June 1765 the colonelcy was assigned to Lieutenant-General James Durand. He died in 1766, and was succeeded by Colonel Hunt Walsh.[9]

Gibraltar

In 1770 the regiment was despatched to Gibraltar, sailing from Cork in May. The regiment was augmented by a light infantry company of seventy men in December 1770, and the ten line companies had their authorised establishment raised by twenty-one men.[10]

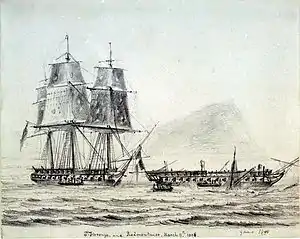

The regiment remained in the Gibraltar garrison for several years, and was present when Spain declared war on the United Kingdom in June 1779 and the Great Siege of Gibraltar began. At this point, the effective regimental strength was 560 men and 27 officers, around a tenth of the garrison. A relief convoy arrived early in 1780, and a second in April 1781, but supplies remained limited. The commander of the garrison decided late in 1781 to attempt a sortie, and this was launched on the night of 26 November; the flank companies of the 56th were part of the raiding force, and successfully destroyed several batteries of artillery.[11]

The siege was finally lifted in February 1783 – after three years and seven months – when the Treaty of Paris ended hostilities, and confirmed British possession of Gibraltar. The 56th received the battle honour "Gibraltar" for its service in the siege, with the right to bear the castle-and-key insignia on its colours. It was relieved in October 1783, and returned to England. Shortly thereafter the regiment was given a county affiliation, part of a move to increase recruiting by linking regiments to local areas, and became the 56th (West Essex) Regiment of Foot.[12]

In the spring of 1784 it moved to garrison duty in Scotland, serving at various stations there until January 1788, when it embarked for Ireland with a reduced establishment of ten companies. From 1788 to 1793 it was stationed in Ireland.[13]

French Revolutionary Wars

With the French Revolution of 1792 the army was expanded in preparation for war; the authorised establishment of the 56th was brought up to twelve companies, and it was ordered to prepare for overseas service.[13] Before hostilities broke out, however, the regiment was involved in suppressing a riot near Wexford in June 1793. Major Valloton, a company commander, was killed along with several local men.[14]

The regiment embarked for the West Indies in November 1793, arriving at Barbados in January 1794, and fought at the capture of Martinique in February. The line companies being left there as a garrison, the light and grenadier companies fought at the capture of St. Lucia in April, and the whole regiment saw service fighting at the capture of Guadeloupe in September. It remained as a garrison in the West Indies for the remainder of 1794, but took great losses from disease. In October, the men still fit for service were transferred to the 6th, 9th and 15th regiments, and the remaining cadre of officers and men embarked to return to England on 3 January 1795.[15]

Arriving in England in February, they were stationed at Chatham to recruit and retrain. The regiment sailed to Cork in September, and after a brief period in Ireland was deemed to have attained "so perfect a state of discipline and efficiency" that it was considered fit for overseas service once more, and despatched to Barbados. It was sent to St. Domingo, and remained there through 1797. On the death of General Walsh, the colonelcy had passed to Major-General Samuel Hulse on 7 March 1795; he did not retain it long, and it was conferred on Major-General Chapple Norton on 24 January 1797. After a period stationed in Jamaica, the regiment returned to England at the end of 1798, again to recruit and rebuild its strength.[16]

In 1799 the regiment was part of the force sent to the Netherlands in the ill-fated Helder Campaign, arriving in Holland in September in time for the Battle of Schoorl-Oudkarspel on the 19th, where it suffered sixty-three officers and men killed or wounded, plus another fifty-nine missing. It fought at Bergen and Egmont-op-Zee on 2 October, before withdrawing from the Netherlands on 18 November.[17]

During 1800 the regiment was stationed in Ireland, and increased its establishment by a further two companies of a hundred men each. The new recruits, since returning from the West Indies in 1799, had been enlisted for service only within Europe; on hearing the announcement of the major victories in the Egyptian campaign in 1801, they promptly offered their services for general service throughout the world. This offer was, however, quickly followed by the Peace of Amiens in 1802, and the regiment remained in Ireland.[18]

Napoleonic Wars

On the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars, a major expansion of the land forces was put in place to deter an invasion; on 25 December 1804, some four hundred men raised in Surrey were placed on the Army establishment as the 2nd Battalion, 56th Regiment, shortly thereafter expanded to 656 men.[19] The existing battalion of the regiment was, accordingly, redesignated as the 1st Battalion, 56th Regiment. Noting the great success the two existing battalions had had with recruiting, a third was later authorised, and raised in 1813 at Horsham as the 3rd Battalion, 56th Regiment.[20]

A detachment of the regiment served on board the frigates Psyche and Piedmontaise as marines in 1809–1810, and fought in a brief war with the Indian kingdom of Travancore in 1809.[21]

1st Battalion

The first battalion moved from Ireland to the Isle of Wight in January 1805, where it was brought to a full strength of a thousand men, and shortly thereafter embarked for Bombay, where it remained as a garrison for several years.[19] In 1808, its strength was augmented to 1300 men.[22] A force of 200 men were detached for service in the Indian Ocean in January 1809, successfully raiding the Île Bourbon in September, capturing a large amount of shipping at anchor.[23]

During this time, in August 1809, the remaining companies of the battalion were shipped from Bombay to Madras at short notice and under great secrecy, in an attempt to make a show of force to avert a possible mutiny of the Indian regiments. This was successful, with any violence being averted, and the regiment received the thanks of the Governor in Council.[24]

In 1810 a second expedition was mounted into the Indian Ocean, with a strong detachment of the first battalion as well as various other units, and the Île Bourbon was taken on 10 July.[25] The same detachment then saw action at the capture of Mauritius in December, the last French territory remaining in the Indian Ocean.[26]

A force of militia volunteers sent as recruits to the 56th arrived as a garrison in Goa in mid-1810. It joined the first battalion in 1811, and the Indian Ocean detachment returned later that year. To mark the regiment's services in India, it received a new pair of colours as a gift from the Honourable East India Company.[27]

With the return of Napoleon to France in 1815, the battalion was again despatched to Mauritius to reinforce the garrison there against the possibility of a revolt by the French population, where it remained.[28]

2nd Battalion

The second battalion moved between various stations in southern England through 1805, being presented with its colours on 28 November at the Isle of Wight.[19] In December it was brought up to an establishment of 866 men, raised to a thousand early in 1806. In March 1806 it moved to Guernsey for garrison duties, returning to the Isle of Wight in early 1807, and embarked for India in June. The two portions of the battalion were split up in a gale, one group putting in at the Cape of Good Hope to refit before continuing to Madras in convoy with HMS Greyhound, arriving in December. The battalion proceeded to Bombay, where it encountered the 1st Battalion for the first time, and moved to Surat in January 1809.[22] At Surat, four companies were detached to aid in the capture of a bandit fort at Mallia in Baroda, returning to the battalion in December.[29]

The battalion expanded its establishment in 1810, rising to an authorised strength of 1,306 men.[27] It suffered greatly from disease during garrison operations in Gujarat in 1813, and again in camp in 1814, losing some three hundred and thirty men between March 1813 and December 1814.[30] However, by January 1815 it had moved to more salubrious climes at Assaye and was able to muster nine hundred men fit for service.[31]

The battalion was ordered to be disbanded as part of the reduction in the army after Waterloo, and marched to Bombay in November 1816. There, four hundred men who volunteered to continue in India were transferred to the 65th Regiment, and the bulk of the regiment sailed for England in January. The line companies were disbanded at Rochester on 25 June, and the flank companies (which had left India in July) at Chatham on 29 December.[32]

3rd Battalion

The third battalion was raised at Horsham in November 1813, and was recruited very rapidly; within a month of its formation, it was reported as ready for service with an establishment of 650 men.[33] It embarked for Holland on 9 December, and fought at the Battle of Merxem on 30 January 1814.[34] After service in the siege of Antwerp, the battalion returned to England after Napoleon's abdication, and was disbanded at Sheerness on 24 October. The men still fit for service were drafted to the first and second battalions, and sent to India.[31]

Peacetime service

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the remaining battalion of the regiment was stationed in Mauritius, where it undertook routine garrison duties and helped suppress the slave trade in the newly acquired colony. A major fire in September 1817 destroyed more than half of Port Louis, the island's capital; the regiment was employed in attempting to fight the fire, and two men were killed.[35] In 1818 General Norton died, and was succeeded in the colonelcy by Lieutenant-General Sir John Murray.[36] The regiment finally returned to England in 1826, after twenty years overseas.[37]

In 1827 it moved to Ireland from Hull, and after General Murray's death, the colonelcy was conferred upon Lieutenant-General Lord Aylmer.[37] The regiment received new colours on 4 April 1828, with the honours "Moro" and "Havannah", as well as the Gibraltar crest and motto.[37] On 23 July 1831 Lieutenant-General Sir Hudson Lowe was appointed to the colonelcy.[38]

Under the 1825 army reforms, six companies would be sent for overseas service at any one time, whilst four remained in the United Kingdom as a depot. Accordingly, when the regiment was ordered to embark for Jamaica in 1831 it took six of its ten companies. Other than a brief epidemic of yellow fever in 1837, claiming sixty men, the time in Jamaica was uneventful.[39] In July 1838, the Sheerness depot provided the guard of honour for the visit of Marshal Soult.[40]

In March 1840 the main body of the regiment sailed aboard Apollo for Canada, to reinforce the garrison there during the Northeastern Boundary Dispute.[41] It returned to England in July 1842, aboard HMS Resistance, where it rejoined its depot companies and moved to Ireland.[42] On 17 November 1842, the Earl of Westmorland was appointed to the colonelcy of the regiment.[43]

The regiment remained at various stations in Ireland, serving to assist in keeping the peace during the widespread repeal movement demonstrations,[43] until it moved to England in 1844.[44] A reserve battalion was formed this year, by organising the existing depot companies, and forming a new depot force.[45] The main force of the regiment moved to Gibraltar in 1847.[44] The reserve battalion was transported to join them in February 1847, aboard the Birkenhead;[46] it later disbanded, with the men transferred to rejoin the main force.[45]

The regiment left Gibraltar in May 1851 aboard the Resistance, for service in Bermuda.[47] In September 1853, an outbreak of yellow fever aboard the convict hulk Thames in Bermuda harbour spread to the barracks; more than two hundred men died.[48] The regiment was ordered home in December 1853.[49]

Crimean War

Whilst the regiment had been ordered home from Bermuda in 1853, it did not sail until late 1854; in the interim, the Crimean War had broken out, and the regiment was put under orders to recruit in Ireland over the winter to full strength, and then sail for Turkey.[50] In December, the first detachment of the regiment sailed for Constantinople.[51]

The second section of the regiment arrived in Dublin from Bermuda in January 1855,[52] where it remained as a depot. Detachments from the depot provided support to the police during unrest at the 1855 by-election in Cavan.[53] The remaining elements of the regiment returned from Bermuda as late as May.[54]

The main force of the regiment was ordered to the Crimea in July.[55] It was originally planned for the regiment to be landed in Kerch to relieve the 71st Foot, but when it arrived it was ordered to land at Sevastopol to reinforce the Allied forces besieging the city.[56] It landed on 25 August, moved into the front lines the next day, and were attached to the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division.[57] The regiment supported the failed attack on the Redan on 8 September; it was not heavily involved, and only one man was wounded.[58]

Sevastopol fell on the 11th, and the regiment was awarded the battle honour "Sevastopol" for its involvement in the attack.[59] Five men of the regiment were awarded the French Military War Medal for "fearless and steady conduct".[60]

The regiment left the Crimea on 12 July 1856, part of the final rearguard to depart. It had served overseas for almost a year, with five men killed in action and thirty deaths due to disease.[61]

Postwar service

On the outbreak of the Indian Mutiny, the regiment was stationed in Ireland; it sailed for India in late August 1857.[62] Whilst it remained in Bombay through the Mutiny, it did not see active service.[63] The Earl of Westmoreland died in October 1859, and was succeeded as colonel by Lieutenant-General John Home Home on the 17th.[64] He, however, died shortly afterwards, and was succeeded by the regiment's twelfth – and final – colonel, Major-General Henry William Breton.[65]

The regiment boarded ships to return from Bombay in March 1866;[65] they arrived at Portsmouth, and took up residence in barracks there, in March 1866.[66] After a spell in England, the regiment moved to Ireland in early 1868, and then embarked for India in February 1871.[44] By late 1877 the regiment had moved to Aden,[67] and was ordered home in early 1878.[44]

Amalgamation and successors

As part of the Cardwell Reforms of the 1870s, where single-battalion regiments were linked together to share a single depot and recruiting district in the United Kingdom, the 56th was linked with the 44th (East Essex) Regiment of Foot, and assigned to district no. 44 at Warley Barracks near Brentwood.[68] On 1 July 1881 the Childers Reforms came into effect and the regiment amalgamated with the 44th (East Essex) Regiment of Foot to form the Essex Regiment.[69] The 56th (as the junior of the two regiments) became the 2nd Battalion, the Essex Regiment.[63]

Whilst the 56th had formally ceased to exist, a degree of individual continuity remained; the 2nd Battalion of the Essex Regiment remained in an independent existence until 1948, when the 2nd Battalion was dissolved and the regiment was amalgamated into a single regular battalion. The Essex Regiment was itself amalgamated into the single-battalion 3rd East Anglian Regiment (16th/44th Foot) in 1958; in 1964, this became the 3rd Battalion, the Royal Anglian Regiment. The 3rd Battalion Royal Anglians was finally disbanded in 1992, with its personnel absorbed by the 1st Battalion.[70]

Traditions

The regiment was originally uniformed with a deep crimson facing colour, which in 1764 was changed to purple. During the 18th century the fugitive nature of the dye required to produce this unusual military colour produced varying shades.[71][72] The colour was often called "pompadour", from which the regiment's nickname of "The Pompadours" came.[73] The reasons for the name of the colour are unclear; it is often said that the shade was Madame de Pompadour's favourite colour. Some soldiers of the regiment preferred to claim that it was the colour of her underwear.[74]

The regimental march, "Rule, Britannia!", commemorated the regiment's past service as marines.[75]

Battle honours

The regiment carried on its colours the battle honours "Moro" and "Sevastopol", as well the Gibraltar castle and key device superscribed "Gibraltar" and subscribed with the motto Montis Insignia Calpe.[65] The battle honour "Havannah" was also granted to the 56th, but not until 1909; as such, it was only ever borne by its successor, the Essex Regiment.[76]

Colonels of the Regiment

Colonels of the Regiment were:[69]

58th Regiment of Foot

- 1755–1761: Maj-Gen. Lord Charles Manners

56th Regiment of Foot - (1756)

- 1761–1765: Lt-Gen. Hon. William Keppel

- 1765–1766: Lt-Gen. James Durand

- 1766–1795: Gen. Hunt Walsh

56th (the West Essex) Regiment of Foot - (1782)

- 1795–1797: F.M. Sir Samuel Hulse, GCH

- 1797–1818: Gen. Hon. Chapple Norton

- 1818–1827: Gen. Sir John Murray, 8th Baronet, GCH

- 1827–1832: Gen. Matthew Aylmer, 5th Lord Aylmer, GCB

- 1832–1842: Lt-Gen. Sir Hudson Lowe, KCB, GCMG

- 1842–1859: Gen. John Fane, 11th Earl of Westmorland, GCB, GCH

- 1859–1860: Lt-Gen. John Home Home

- 1860–1881: Gen. Henry William Breton

Notes

- Awarded to successor Essex Regiment in 1909

- Historical Record of the Fifty-Sixth, or the West Essex Regiment of Foot, Richard Cannon, Parker, Furnivall and Parker, London, 1844, p. 9

- Cannon, pp. 9–10

- Cannon, p. 11

- Cannon, pp. 11–12

- Cannon, pp. 12–13

- This distinction is unusual both for being the first battle honour granted for an individual action in a larger engagement, as well as for being one of the few battle honours received by a regiment on its first active service. It is also unique to the 56th; no other regiment was granted the honour. (Baker, p. 45)

- Cannon, p. 13

- Cannon, pp. 13–14

- Cannon, pp. 14–15

- Cannon, pp. 15–18

- Cannon, p. 21

- Cannon, p. 22

- Cannon, pp. 22–23

- Cannon, pp. 23–24

- Cannon, pp. 24–25

- Cannon, pp. 25–27

- Cannon, pp. 25–29

- Cannon, p. 29

- Cannon, p. 39

- Cannon, pp. 34–35

- Cannon, p. 30

- Cannon, pp. 30, 33

- Cannon, pp. 35–36

- Cannon, p. 36

- Cannon, p. 37

- Cannon, p. 38

- Cannon, p. 44-45

- Cannon, pp. 31–32

- Cannon, pp. 39, 43

- Cannon, p. 43

- Cannon, pp. 46–7

- Cannon, p. 40

- Cannon, p. 41

- Cannon, pp. 46–47

- Cannon, p. 47

- Cannon, p. 48

- Cannon, p. 50

- Cannon, pp. 50–51

- Article in The Times, 31 July 1838

- Cannon, p. 51

- Cannon, p. 52

- Cannon, p. 53

- "56th (West Essex) Regiment of Foot: locations". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 20 April 2007. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- "2nd Battalion, 56th Regiment of Foot". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 18 April 2007. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Article in The Times, 15 February 1847

- Article in The Times, 4 June 1851

- Medical and surgical history of the British Army, p. 332

- Article in The Times, 21 December 1853

- Article in the Aberdeen Journal, 15 November 1854

- Article in Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper, 17 December 1854

- Article in the Freeman's Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser, 16 January 1855

- Article in the Morning Chronicle, 20 March 1855

- Article in the Daily News, 19 May 1855

- Health of the Army in Turkey and the Crimea, p. 332

- Russell, p. 97

- Medical and surgical history of the British Army, p. 332; Russell, p. 98

- Russell, p. 166

- Baker, p. 273

- Carter, p. 135

- Medical and surgical history of the British Army, p. 333

- Hart's annual Army list, Militia list, and Imperial Yeomanry list, 1859. p. 276. Digitised copy

- "The 19th Century". Chelmsford City Council. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "No. 22320". The London Gazette. 28 October 1859. p. 3886.

- Hart's annual Army list, Militia list, and Imperial Yeomanry list, 1867. p. 324. Digitised copy

- Article in The Times, 27 March 1866

- Article in The Times, 23 October 1877

- "Training Depots". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 10 February 2006. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- "56th (West Essex) Regiment of Foot". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- "Between the Wars, The Second World War and Post War". Chelmsford City Council. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Carman, p. 80

- Cannon, p. 14. Wickes, p. 83, notes that the intention originally was to change to blue, but this was not allowed as it was not a royal regiment.

- Cannon, p. 10

- Holmes, p. 43

- Wickes, p. 83

- Matthews, p. 66

References

- Baker, Anthony (1986). Battle Honours of the British and Commonwealth Armies. Littlehampton Book Services. ISBN 0-7110-1600-3.

- Carman, W.Y. (1985). Uniforms of the British Army. Webb & Bower. ISBN 978-0863500312.

- Carter, Thomas (1861). Medals of the British army : and how they were won. Groombridge and Sons.

- Cannon, Richard (1844). . London: Parker, Furnivall and Parker – via Wikisource. [scan

]

] - Holmes, Richard (2002). Redcoat (paperback). London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-653152-0.

- Matthews, Charles (1993). For love of regiment: a history of the British infantry. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-0850523713.

- Russell, W. H. (1856). The war: from the death of Lord Raglan to the evacuation of the Crimea. G. Routledge.

- Wickes, H. L. (1974). Regiments of foot: a historical record of all the foot regiments of the British Army. Osprey. ISBN 0-85045-220-1.

- Medical and surgical history of the British Army which served in Turkey and the Crimea during the war against Russia, Vol. I. Harrison and Sons. 1858. Digitised copy