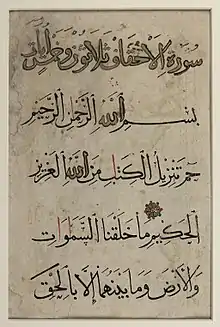

Al-Ahqaf

Al-Ahqaf (Arabic: الأحقاف, al-aḥqāf; meaning: "the sand dunes" or "the winding sand tracts") is the 46th chapter (surah) of the Qur'an with 35 verses (ayat). This is the seventh and last chapter starting with the Muqattaʿat letters Hāʼ Mīm. Regarding the timing and contextual background of the supposed revelation (asbāb al-nuzūl), it is one of the late Meccan chapters, except for verse 10 and possibly a few others which Muslims believe were revealed in Medina.

| اَلْأَحْقَافُ Al-Aḥqāf The Wind-Curved Sandhills | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Meccan |

| Other names | The Dunes, The Sandhills, The Sand-Dunes |

| Position | Juzʼ 26 |

| No. of Rukus | 4 |

| No. of verses | 35 |

| Opening muqaṭṭaʻāt | Ḥā Mīm حم |

| Quran |

|---|

|

|

The chapter covers various topics: It warns against those who reject the Quran, and reassures those who believe; it instructs Muslims to be virtuous towards their parents; it tells of the Prophet Hud and the punishment that befell his people, and it advises Muhammad to be patient in delivering his message of Islam.

A passage in chapter 15, which talks about a child's gestation and weaning, became the basis by which some Islamic jurists determined that the minimum threshold of fetal viability in Islamic law would be about 25 weeks. The name of the chapter comes from verse 21, where Hud is said to have warned his people "by the sand dunes" (bī al-Ahqaf).

Revelation history

According to the Islamic tradition, Al-Ahqaf is one of the late Meccan chapters, chapters which were largely revealed before Muhammad's hijrah (migration) to Medina in 622 CE. Most Quranic commentators say that the tenth verse was revealed during the Medinan period—the period after Muhammad's Hijrah. There are minority opinions that say verse 15 and verse 35 were also revealed during the Medinan period. Another minority opinion argues that the entire chapter was revealed in the Meccan period.[1]

The traditional Egyptian chronology places the chapter as 66th in order of revelation; in the chronology of orientalist Theodor Nöldeke it is 88th.[2] An academic commentary of the Quran, The Study Quran, based on a range of traditional commentators, dates the chapter's revelation to two years before the hijra, around the same time as the revelation of Chapter 72 Al-Jinn.[1]

Content

The chapter begins with a Muqattaʿat, the two-letter formula Hā-Mīm, the last of the seven chapters to do so. In the Islamic tradition, the meanings of such formulae at the beginnings of chapters are considered to be "known only to God".[3] The following verses (2–9) warn against those who reject the Quran and reiterate the Quranic assertion that the verses of the Quran are revealed from God and were not composed by humans.[1] The verses maintain that the Quran itself is a "clear proof" of God's signs, and challenge the disbelievers to produce another scripture, or "some vestige of knowledge", to justify their rejection.[2][4][5]

Verse ten describes a "witness from the Children of Israel" who accepted the revelation. Most Quranic commentators believe that this verse—unlike most of the chapter—was revealed in Medina and the witness refers to Abdullah ibn Salam, a prominent Jew of Medina who converted to Islam, and whom Muhammad was reported to have described as one of the "People of Paradise". A minority—who believe that this verse was revealed in Mecca–say that the witness is Moses who accepted the Torah.[6]

Verses 13 and 14 talks about the believers who "stand firm", to whom "no fear shall come ... nor shall they grieve". The exegete Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209) says that this means that the believers will not have to fear punishment or many other trials on the Day of Judgement. The believers are described as "those who say 'Our Lord is God'", without specific references to Islam, possibly meaning that this includes the adherents of all Abrahamic religions. This is related to verse 59 of Al-Ma'ida which says that "those who are Jews, and the Christians, and the Sabians—whosoever believes in God and the Last Day and works righteousness" will be rewarded by God, and on them "no fear shall come ... nor shall they grieve".[7]

Verses 15 to 17 instruct Muslims to be virtuous (ihsan) towards their parents and do not disobey them. A passage in verse 15 notes that a mother works hard for a period of "thirty months", bearing and nursing her child; the explicit mention of "thirty months" has implications for the calculation of the fetal viability threshold in Islamic law (see #Fetal viability below).[1][8]

Verses 21 to 25 contain the story of the Islamic prophet Hud, who was sent to the people of ʿĀd "by the sand dunes" (Arabic: fi al-Ahqaf, hence the name of the chapter). The people rejected his message and were then punished by a storm that destroyed them.[1][9] The next verses warn the polytheists of Quraysh—who opposed Muhammad's message of Islam—that they could also be destroyed just as the people of ʿĀd had been destroyed. The last verse (35) is addressed to Muhammad and instructs him to be patient in the face of rejections of his message, just as the previous prophets of Islam were patient.[1]

Etymology

.jpg.webp)

The name al-Ahqaf, translated as "the sand dunes" or "the winding sand tracks", is taken from verse 21 of the chapter,[1] which mentions "the brother of ʿĀd" (a nickname for the ancient Arabian prophet Hud), who "warned his people by the sand dunes". According to the 15th-16th century Quranic commentary Tafsir al-Jalalayn, "Valley of Ahqaf" was the name of the valley, located today in Yemen, where Hud and his people lived.[4][10]

Fetal viability

Verse 15 of the chapter talks about the period of gestation and breastfeeding, saying that "His mother bears him with hardship and she brings him forth with hardship, and the bearing of him, and the weaning of him is thirty months ...". Another verse in the Quran, Chapter 2, Verse 233 speaks of mothers nursing their children for two full years. Some Islamic jurists interpret the six-month time difference between the durations found in these two verses as being the threshold of fetal viability in Islamic law.[11]

Based on this reasoning, Saudi Arabia's Permanent Committee for Scholarly Research and Ifta issued a fatwa (legal opinion) in 2008, saying that resuscitation of premature newborns was only required for infants of at least 6 lunar months (25 weeks and 2 days) gestation. In the cases of infants born before this period, the fatwa allowed two "specialist physicians" to study the conditions and decide whether to provide resuscitation or to leave the child to die. According to a group of Saudi pediatric practitioners, in a paper published in Current Pediatric Reviews in 2013, this opinion reduces the legal consequences for the deciding physicians, up to the 25th week of gestation, and accordingly Saudi hospitals are less aggressive at resuscitating premature infants below this threshold.[11][12]

See also

References

Citations

- The Study Quran, p. 1225.

- Ernst 2011, p. 40.

- The Study Quran, p. 1226, v.1 commentary.

- "Qur'anic Verses (56:77-9) on Carpet Page". World Digital Library. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- The Study Quran, pp. 1226–1227, vv. 4–7 commentaries.

- The Study Quran, p. 1228, v.10 commentary.

- The Study Quran, p. 1229, vv.13–14 commentary.

- The Study Quran, pp. 1229–1330, vv.15–17 commentary.

- The Study Quran, pp. 1331, vv.21–25 commentary.

- The Study Quran, p. 1231, v.21 commentary.

- McGuirl & Campbell 2016, p. 696.

- Al-Alaiyan et al. 2013, p. 5.

Bibliography

- Al-Alaiyan, Saleh; Al-Abdi, Sameer; Alallah, Jubara; Al-Hazzani, Fahad; AlFaleh, Khalid (2013). "Pre-viable Newborns in Saudi Arabia: Where are We Now and What the Future May Hold?". Current Pediatric Reviews. Bentham Science. 9 (39): 4–8. doi:10.2174/157339613805289497.

- Ernst, Carl W. (5 December 2011). How to Read the Qur'an: A New Guide, with Select Translations. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-6907-9.

- McGuirl, J.; Campbell, D. (2016). "Understanding the role of religious views in the discussion about resuscitation at the threshold of viability". Journal of Perinatology. Springer Nature. 36 (9): 694–698. doi:10.1038/jp.2016.104. PMID 27562182.

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr; Caner K. Dagli; Maria Massi Dakake; Joseph E.B. Lumbard; Mohammed Rustom, eds. (2015). The Study Quran: A New Translation and Commentary. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-112586-7.