Alalakh

Alalakh (Hittite: Alalaḫ) was an ancient city-state, a late Bronze Age capital in the Amuq River valley of Turkey's Hatay Province. It was occupied from before 2000 BC, when the first palace was built, and likely destroyed in the 12th century BC and never reoccupied. The city contained palaces, temples, private houses and fortifications. Modern Antakya has developed near the site.

Alalaḫ | |

.JPG.webp) Archaeological site of Alalakh (Tell Açana) | |

Shown within Turkey | |

| Alternative name | Tell Atchana |

|---|---|

| Location | Hatay Province, Turkey |

| Region | Levant |

| Coordinates | 36°14′16″N 36°23′05″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | 2nd millennium BC |

| Abandoned | 12th century BC |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

The remains of Alalakh have formed an extensive mound; the modern archaeological site is known as Tell Atchana. It was first excavated in the 1930s and 1940s by a British team. A team sponsored by the University of Chicago started surveys in the late 20th century, and has conducted excavations led by K. Aslihan Yener in the early 21st century. She is now leading work sponsored by Mustafa Kemal University and the Turkish government.

History

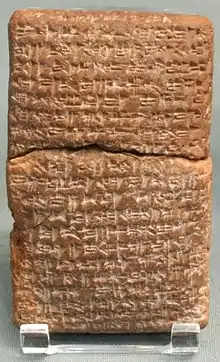

| Treaty clay tablet | |

|---|---|

Fugitive slave treaty between Idrimi of Alalakh (now Tell Atchana) and Pillia of Kizzuwatna (now Cilicia) | |

| Size | Length: 12 cm (4.7 in) Width: 6.4 cm (2.5 in) |

| Writing | cuneiform |

| Created | 1480BC (about) |

| Present location | Room 54, British Museum, London |

| Identification | 131447 |

Alalakh was founded by the Amorites (in the territory of present-day Turkey) during the early Middle Bronze Age in the late 3nd millennium BC. The first palace was built c. 2000 BC, contemporary with the Third Dynasty of Ur.

Middle Bronze II

The written history of the site may begin under the name Alakhtum, with tablets from Mari in the 18th century BC, when the city was part of the kingdom of Yamhad (modern Aleppo). A dossier of tablets records that King Sumu-Epuh sold the territory of Alakhtum to his son-in-law Zimri-Lim, king of Mari, retaining for himself overlordship. After the fall of Mari in 1765 BC, Alalakh seems to have come under the rule of Yamhad again. King Abba-El I of Aleppo bestowed it upon his brother Yarim-Lim, to replace the city of Irridu. Abba-El had destroyed the latter after it revolted against his brother Yarim-Lim.[1] In the 18th to 17th centuries period transition, Alalakh was under the reign of king Yarim-Lim, and was the capital of the city-state of Mukiš and vassal to Yamhad, centered in modern Aleppo.[2] A dynasty of Yarim-Lim's descendants was founded, under the hegemony of Aleppo, that lasted to the 16th century. According to the short chronology found at Mari, at that time Alalakh was destroyed, most likely by Hittite king Hattusili I, in the second year of his campaigns. However, as per middle chronology and new publications by archaeologist K. A. Yener, destruction of Alalakh by Hattusili I can be firmly located as a "Fire and Conflagration" around 1650 BC.[3]

Late Bronze

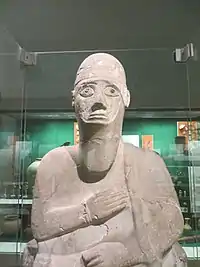

After a hiatus of less than a century, written records for Alalakh resume. At this time, it was again the seat of a local dynasty. Most of the information about the founding of this dynasty comes from a statue inscribed with what seems to be an autobiography of the dynasty's founding king.[4]

According to his inscription, in the 15th century BC, Idrimi, son of the king of Yamhad, may have fled his city for Emar, traveled to Alalakh, gained control of the city, and been recognized as a vassal by Barattarna. The inscription records Idrimi's vicissitudes: after his family had been forced to flee to Emar, he left them and joined the "Hapiru people" in "Ammija in the land of Canaan." The Hapiru recognized him as the "son of their overlord" and "gathered around him"; after living among them for seven years, he led his Habiru warriors in a successful attack by sea on Alalakh, where he became king.

However, according to the archeological site report, this statue was discovered in a level of occupation dating several centuries after the time that Idrimi lived. There has been much scholarly debate as to its historicity. Archeologically-dated tablets recount that Idrimi's son Niqmepuh was contemporaneous with the Mitanni king Saushtatar. This seems to support the inscription on the statue claiming that Idrimi was contemporaneous with Barattarna, Saushtatar's predecessor.[5]

The socio-economic history of Alalakh during the reign of Idrimi's son and grandson, Niqmepuh and Ilim-ilimma, is well documented by tablets excavated from the site. Idrimi is referred to rarely in these tablets.

In the mid-14th century BC, the Hittite Suppiluliuma I defeated king Tushratta of Mitanni and assumed control of northern Syria, then including Alalakh, which he incorporated into the Hittite Empire. A tablet records his grant of much of Mukish's land (that is, Alalakh's) to Ugarit, after the king of Ugarit alerted the Hittite king to a revolt by the kingdoms of Mukish, Nuhassa, and Niye. The majority of the city was abandoned by 1300 BC.[6] Alalakh was probably destroyed by the Sea People in the 12th century BC, as were many other cities of coastal Anatolia and the Levant. The site was never reoccupied, the port of Al Mina taking its place during the Iron Age.

Archaeology

Tell Atchana was excavated by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in the years 1937–1939 and 1946–1949. His team discovered palaces, temples, private houses and fortification walls, in 17 archaeological levels reaching from late Early Bronze Age (Level XVII, c. 2200–2000 BC to Late Bronze Age (Level 0, 13th century BC). Among their finds was the inscribed statue of Idrimi, a king of Alalakh c.early 15th century BC. [7]

After several years' surveys in the late 20th century, the University of Chicago team had its first full season of excavation in 2003 directed by K. Aslihan Yener. In 2004, the team had a short excavation and study season in order to process finds.[8][9][10][11] In 2006 the project changed sponsorship and resumed excavations directed by Aslihan Yener under the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism and Mustafa Kemal University in Antakya.

About five hundred cuneiform tablets were retrieved at Level VII, (Middle Bronze Age) and Level IV (Late Bronze Age).[12] The inscribed statue of Idrimi, a king of Alalakh c. early 15th century BC, has provided a unique autobiography of Idrimi's youth, his rise to power, and his military and other successes. The statue is now held in the British Museum. Akkadian texts from Alalakh primarily consist of juridical tablets, which record the ruling family's control over land and the income that followed, and administrative documents, which record the flow of commodities in and out of the palace. In addition, there are a few word lists, astrological omens and conjurations.

Notes

- Donald J. Wiseman, Abban and Alalah, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 12, pp. 124-129, 1958

- Johnson, Michael Alexander, (2020). Crafting Culture at Alalakh: Tell Atchana and the Political Economy of Metallurgy, The University of Chicago, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, p. 1.

- Ingman, Tara, et al., (2020). "Human mobility at Tell Atchana (Alalakh) during the 2nd millennium BC: integration of isotopic and genomic evidence", in bioRxiv preprint, Table 1. Chronology of Tell Atchana, pp. 6-7.

- "IDRIMI INSCRIPTION". Archived from the original on 2009-10-20.

- W. F. Albright, "Further Observations on the Chronology of Alalah," Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, vol. 146, pp. 26-34, 1957

- Eric H. Cline, 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed, p. 124

- Leonard Woolley, Alalakh, An Account of the Excavations at Tell Atchana 1937-1949 (Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London), Oxford, 1955

- K. Aslihan Yener, Alalakh: A Late Bronze Age Capital In The Amuq Valley, Southern Turkey, Oriental Institute, 2001

- K. Aslihan Yener, "Tell Atchana (Ancient Alalakh) Survey 2001," in Oriental Institute 2001-2002 Annual Report, pp. 13–19, 2002

- K. Aslihan Yener, Amuq Valley Regional Projects: Tell Atchana (Alalakh) 2002, Oriental Institute, 2003

- Yener et al., Reliving the Legend: The Expedition to Alalakh 2003, Oriental Institute, 2004

- Jesse Casana, Alalakh and the Archaeological Landscape of Mukish: The Political Geography and Population of a Late Bronze Age Kingdom, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 353 , pp. 7-37, (February 2009)

References

- Donald J. Wiseman, 1953. The Alalakh Tablets, (London: British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara); reviewed by Joan Lines in American Journal of Archaeology 59.4 (October 1955), pp. 331–332; Reprinted 1983 in series AMS Studies in Anthropology ISBN 0-404-18237-2

- Frank Zeeb, "Die Palastwirtschaft in Altsyrien nach den spätaltbabylonischen Getreidelieferlisten aus Alalah (Schicht VII)", Alter Orient und Altes Testament, no. 282. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-934628-06-0

- Marlies Heinz, Tell Atchana, Alalakh. Die Schichten VII-XVII, Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1992.

- Nadav Na'aman, "The Ishtar Temple at Alalakh," Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 209–214, 1980

- Juan Oliva, "New Collations and Remarks on Alalakh VII Tablets," Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 64, no.1, pp. 1–22, 2005

- Dominique Collon, The Seal Impressions from Tell Atchana/Alalakh (Alter Orient und Altes Testament), Butzon & Bercker, 1975, ISBN 3-7666-8896-0

- Amir Sumaka'i Fink, Late Bronze Age Tell Atchana (Alalakh): Stratigraphy, chronology, history, British Archaeological Reports, 2010, ISBN 1-4073-0661-8

- C. E. Morris and J. H. Crouwel, "Mycenaean Pictorial Pottery from Tell Atchana (Alalakh)," The Annual of the British School at Athens, vol. 80, pp. 85–98, 1985

- C. Leonard Woolley, Alalakh: An Account of the Excavations at Tell, Oxford University Press, 1955

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alalakh. |

- official web site of the Alalakh Excavations.

- Alalakh Notice and a basic bibliography.

- Stone guardian lions of Alalakh

- S. Riehl, "Late Bronze Age Tell Atchana" Archaeobotany at Tell Atchana (Tübingen University)