Ascendonanus

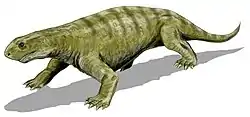

Ascendonanus (meaning "climbing dwarf") is an extinct genus of varanopid "pelycosaurian" synapsid from the Early Permian of Germany.[1] It is the earliest specialized arboreal (tree-living) vertebrate currently known and resembled a small lizard, although it was related to mammals. The fossils of Ascendonanus are of special scientific importance because they include remains of skin, scales, scutes, bony ossicles, and body outlines, indicating that some of the oldest relatives of mammals had a scaly "reptilian-type" appearance. The animal was about 40 cm long, with strongly curved claws, short limbs, a slender, elongated trunk, and a long tail. It would have preyed on insects and other small arthropods.[1]

| Ascendonanus | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | †Ascendonanus Spindler et al., 2018 |

| Type species | |

| †Ascendonanus nestleri Spindler et al., 2018 | |

Ascendonanus was named and described in 2018 from remains of five individuals that were discovered in the Chemnitz petrified forest, an Early Permian tropical fossil forest preserved under the city of Chemnitz, Germany. A Pompeii-like pyroclastic volcanic eruption 291 million years ago[2] buried the forest and created the Zeisigwald Tuff Horizon in the uppermost Leukersdorf Formation (late Sakmarian/early Artinskian transition stage), preserving some of the animals that lived there in exceptional detail in a bottom layer of volcanic ash.[1]

The type species name Ascendonanus nestleri honors Knut Nestler, a long-time local supporter (deceased) of the Chemnitz Museum of Natural History (Museum für Naturkunde Chemnitz (MNC)), where the specimens of Ascendonanus are stored.[1]

Description

Ascendonanus was about 40 cm long, although the end of the tail is missing in all specimens and the full body length in life is not currently known. It is the smallest known member of the clade Varanopidae, a group of early synapsids that generally resembled the unrelated monitor lizards. Features that identify Ascendonanus as a "pelycosaur" grade synapsid and a member of the Varanopidae include a single lateral temporal opening (fenestra) in the skull, a ridge on the underside of the centra of the vertebrae, and enlarged blades on the ilium of the pelvis.[1]

Specimens

The five recovered fossils of Ascendonanus are strongly compacted and were split open as flattened counterslabs that revealed articulated partial or near complete skeletons with remains of soft tissue and some internal features. The bone material itself, however, often was not clearly preserved, making interpretation of some details more difficult. The specimens were CT scanned to reveal additional information. Based on the ossification of different bones, all individuals appear to be fully grown despite some differences in size.[1]

The specimen designated MNC-TA0924 was made the diagnostic holotype of Ascendonanus nestleri because it provides the clearest details of the skull. The most remarkable specimen (MNC-TA1045) preserves the clear body outline of nearly the entire animal on counterslabs, showing the thickness in life of the limbs and the neck, and the full covering of scales.[3][1][4]

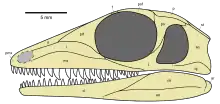

Skull

Because of compaction over time, it is not known if the skull is relatively flat or if it has a taller profile. The tip of the snout is not well preserved in any specimens. The orbits are very large but the sclerotic rings to support the eyeball are not ossified. Some specimens preserve dozens of tiny round dermal bones or ossicles that were embedded in the skin of the upper eyelid. Such eyelid ossicles are currently not known in any other amniotes, but have been found in some dissorophid temnospondyl amphibians, a non-amniote tetrapod group that is not closely related to synapsids. The eyelid ossicles in Ascendonanus may have evolved independently or may be an ancient feature retained from the earliest tetrapods. Such eyelid ossicles are distinct from the rod-like dermal bones, called palpebral bones, that evolved above the eye socket in a number of later non-synapsid groups, including some ornithischian dinosaurs. The pointed teeth are slender, without flattened cross-sections, serrations, or a cutting edge, and are moderately recurved in the upper jaw and straighter in the lower jaw.[1]

Skeleton

Ascendonanus differs notably from other varanopids in its elongated trunk section, with 34 to 37 presacral vertebrae compared to 26 in most synapsids. It has a dense set of thin belly ribs or gastralia along the underside. The full length of its tail is not known based on current fossils, but it was longer than in other described varanopids and would have helped with balance in climbing, similar to some tree-living lizards with very long tails. It is unknown whether the distal part of the tail was prehensile.[1]

Limbs

The forelimbs are almost as long as the hindlimbs, but both pairs of legs are very short compared to the length of the trunk. The elements of the feet are enlarged, with elongated and slender digits. Distinct from other varanopids, the claws on Ascendonanus have a very strong curvature. The curved claws and the size and shape of the feet, including a longer fourth digit on the manus and on the pes, indicate Ascendonanus would have been a "clinging" climber rather than a "grasping" climber.[1][5]

Skin and scales

The specimens show a regular scale pattern over their bodies, similar to living squamates and archosaurs, suggesting dry, scaly skin was present in the earliest amniotes before the split into synapsids and sauropsids (reptiles) during the Carboniferous Period. Some synapsid groups later developed bare, glandular skin, eventually with hair and whiskers that became characteristics of mammals. Unlike some varanopids (such as Archaeovenator and Microvaranops), Ascendonanus does not have dorsal osteoderms on its upper trunk section along the back. However, the middle part of the tail has a covering of small scutes that continues to where the end of the tail is missing in all current specimens. The body outlines preserved show that Ascendonanus had a plump neck and muscular thighs (although the femur bone itself is relatively thin) on its short hindlimbs, while the trunk and the forelimbs are relatively slender.[1]

Discovery

Hilbersdorf scientific excavation

All of the current fossils of Ascendonanus were discovered during a test dig by the Chemnitz Museum of Natural History in the Hilbersdorf district of Chemnitz between April 2008 to October 2011.[4] The site was limited to a pit 24 m by 18 m, down to a depth of at least 5 m, and was the first systematic scientific excavation of the Chemnitz fossil forest ever conducted in the city. The museum began a second, more extensive, and ongoing, dig in the Sonnenberg district in 2014. In addition to finding fossils of trees and plants at the Hilbersdorf site, the team recovered remains of vertebrates (synapsids, temnospondyl, aistopods) and arthropods (scorpions, Arthropleura, spiders), some later identified as species new to science.[1]

Taphonomy

During an early phase of the volcanic eruption, rising rhyolitic magma came into contact with groundwater, exploding molten rock into tiny fragments mixed with steam, resulting in falls of wet, relatively cool, fine volcanic ash particles.[2] An initial ash layer covered the ground and knocked leaves off trees, but left the trunks standing.[4]

All of the Acendonanus specimens were found close to the base of upright fossil trees from which the animals evidently had fallen to the ground onto the first ash fall, either after being dislodged by a volcanic blast[4] or, more likely, after being overcome by breathing ash particles or toxic gases, or possibly by lethal temperatures.[1] A second fall of wet ash quickly buried the Ascendonanus individuals and the other animals that were on or under the forest floor up to about 53 cm deep, preventing decay and preserving bodies largely intact (but compacted over time), with detailed impressions or traces of soft tissues. The fossil plant material in the wet ash layer shows no evidence of charring, indicating that the temperature of the ash fall was below 280° C.[1]

Later, more violent phases of the eruption covered the wet ash layer in much deeper deposits of coarser hot pyroclastic material that make up most of the Zeisigwald Tuff Horizon (total depth up to 4 m).[2] The upper trunks and branches of embedded upright trees were snapped off above about 1 m to 3 m from the ground.[4]

References

- Frederik Spindler; Ralf Werneburg; Joerg W. Schneider; Ludwig Luthardt; Volker Annacker; Ronny Rößler (2018). "First arboreal 'pelycosaurs' (Synapsida: Varanopidae) from the early Permian Chemnitz Fossil Lagerstätte, SE Germany, with a review of varanopid phylogeny". PalZ. 92 (2): 315–364. doi:10.1007/s12542-018-0405-9.

- Ludwig Luthardt; Mandy Hofmann; Ulf Linnemann; Axel Gerdes; Linda Marko; Ronny Rößler (2018). "A new U-Pb zircon age and a volcanogenic model for the early Permian Chemnitz Fossil Forest". International Journal of Earth Sciences. in press. doi:10.1007/s00531-018-1608-8.

- Photo of Ascendonanus specimen TA1045 in Chemnitz Museum of Natural History. https://sachsen.museum-digital.de/index.php?t=objekt&oges=8453

- Ronny Rößler; Thorid Zierold; Zhuo Feng; Ralph Kretzschmar; Mathias Merbitz; Volker Annacker; Jörg W. Schneider (2012). "A Snapshot of an Early Permian Ecosystem Preserved by Explosive Volcanism: New Results from the Petrified Forest of Chemnitz, Germany". PALAIOS. 27 (11): 315–364. doi:10.2110/palo.2011.p11-112r.

- Jörg Fröbisch; Robert R. Reisz (2009). "The Late Permian herbivore Suminia and the early evolution of arboreality in terrestrial vertebrate ecosystems". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 276 (1673): 3611–3618. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0911. PMC 2817304. PMID 19640883.